Let Me Count the Ways

Quantifying affection

Latif Nasser

“How can you measure love?” pioneering sexologist Alfred Kinsey asked in a 1954 issue of Time. “Nobody knows how to approach it scientifically.” To be fair, Kinsey was dodging criticism that his own sex surveys ignored complex human emotion. Yet his pessimism on the matter of quantifying love is telling. Here was an ardent booster of science, a calculator of the most intimate aspects of human relationships, throwing his hands up at the prospect of measuring so slushy a sentiment.

And what a challenge it is. The most sophisticated researcher wielding the most sensitive tool can hardly appraise a feeling so mercurial, so intimate, and so irrational without a laundry list of disclaimers. In academia and our individual lives alike, true love has always been beyond measure.

Nonetheless, for the last century or so, inventive minds have striven to enumerate love whether by reading lovers’ bodies, minds, or brains. Some of these efforts were populist and practical, offering advice, say, to insecure romantics questioning the mysteries of their own hearts. Others were scientific and abstract, aspiring to ground the study of our most subjective selves in objective metrics and data.

On its own, each of these quixotic efforts reflects nothing so much as its inventor’s working definition of love and the latest introspective technology available at the time. Yet, surprisingly, when strung together, the portrait of love that emerges is multifarious, chimerical. It’s a portrait of loves, united by nothing so much as a single—and singularly capacious—word. Psychologist of love Bernard Murstein once wrote that love is “an Austro-Hungarian Empire uniting all sorts of feelings, behaviors, and attitudes, sometimes sharing little in common.” It’s enough to make you wonder whether love remains beyond measure not because it is too deeply felt, but rather because it’s too broadly labeled.

What follows is a miscellany of efforts to quantify love from around the empire.

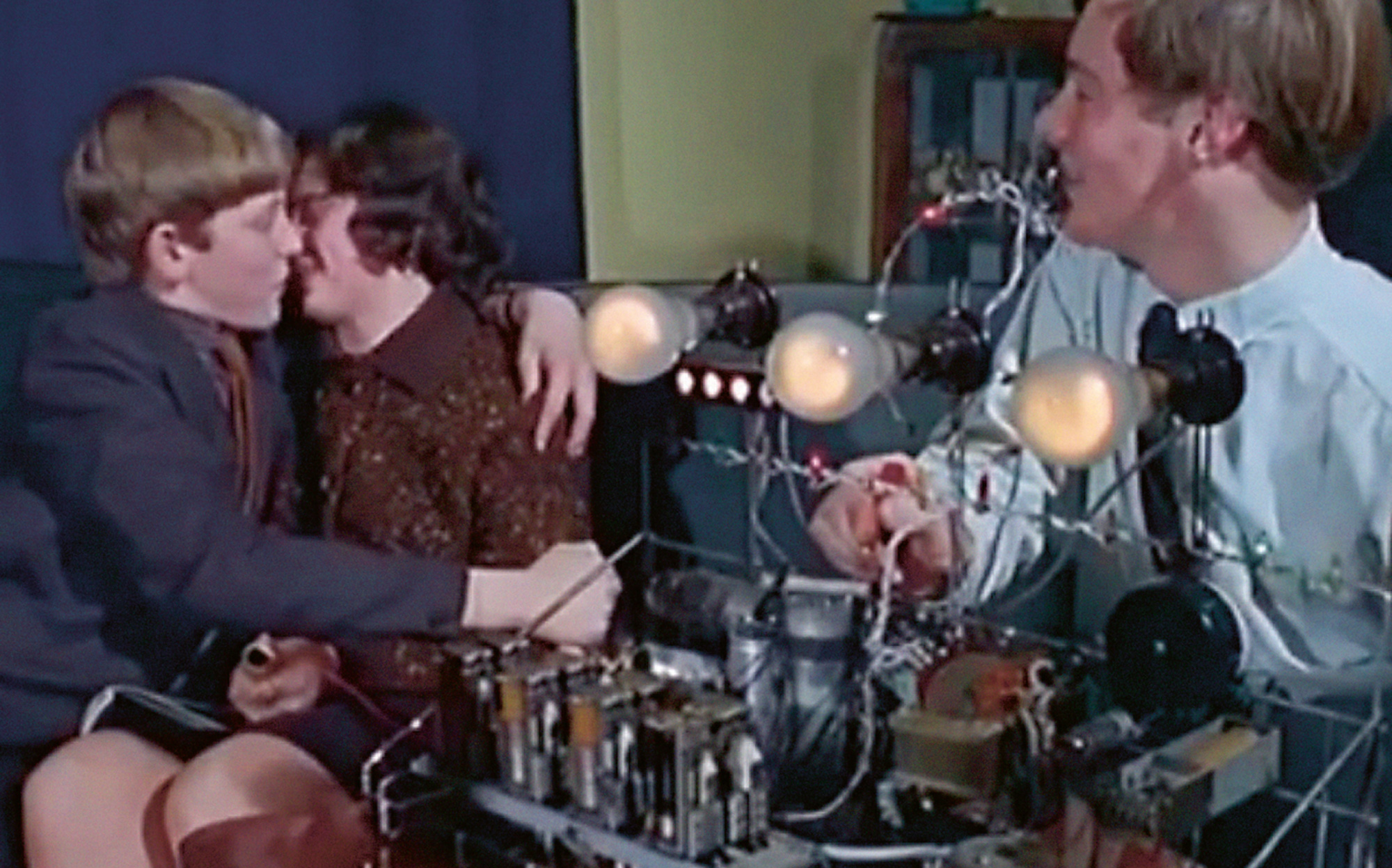

In 1874, glassware manufacturer William Holzer fashioned a toy known as the “sympathy thermometer, or philosophic love tester.” (Its design is lost to history; one presumes it worked much like a contemporary glass hand boiler, responding to the warmth of the user’s hand.) Only with the advent of penny arcades in the first decades of the twentieth century, however, did America fall for love testers. Most of these coin-operated devices—such as the Kiss-O-Meter, the Magic Heart, the Three Wheels of Love, the Love Pilot, the Love Analyzer, and the Love Teller—measured physical signs like galvanic skin response or grip strength. The lit-up rankings typically corresponded to a heat-related descriptor, from “Ice Lips” to “Cool and Calm” to “Steamy” to “Sizzling.” As late as 1953, a Life photo spread listed the love tester among the top