Autobiographical Bodies

Reading “Sparraw’s Kneecaps”

Alice Butler

It could be a doorstop, a paperweight; a telephone directory, or a diary. It could be a “book” if its one-thousand-odd pages had found a publisher back in 1974. (But they didn’t.) And so it remains static and singular—categorically, but not materially, dead. Searching for the word we might call it to make it safe—this unpublished, peripheral object—I’m going to say it’s a manuscript. In Dodie Bellamy’s The Letters of Mina Harker, the epistle-maker is nicknamed MS, code for “Manuscript”: a textual body, living through ink and paper, she is “her own scandalous invention.”[1]

• • •

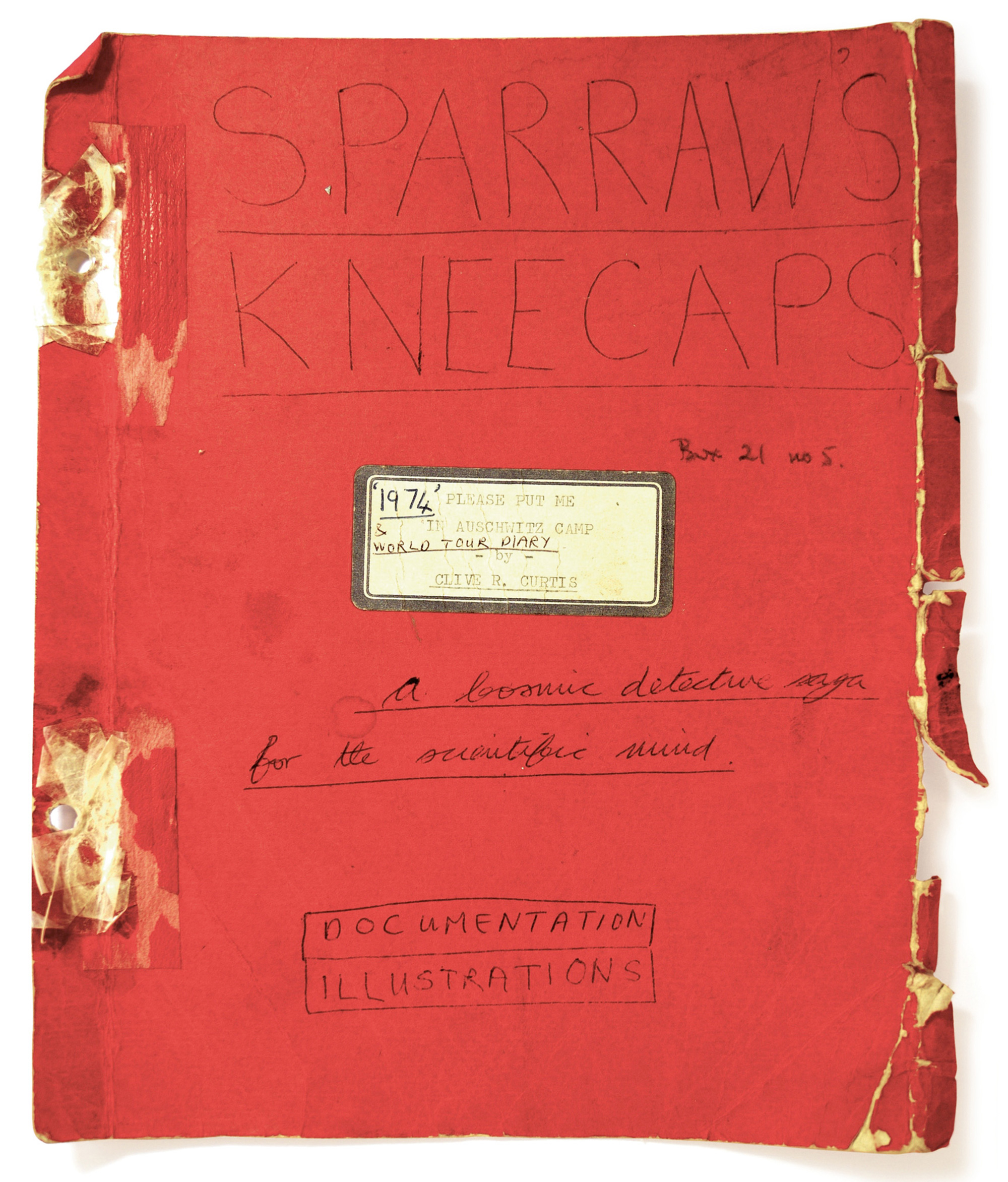

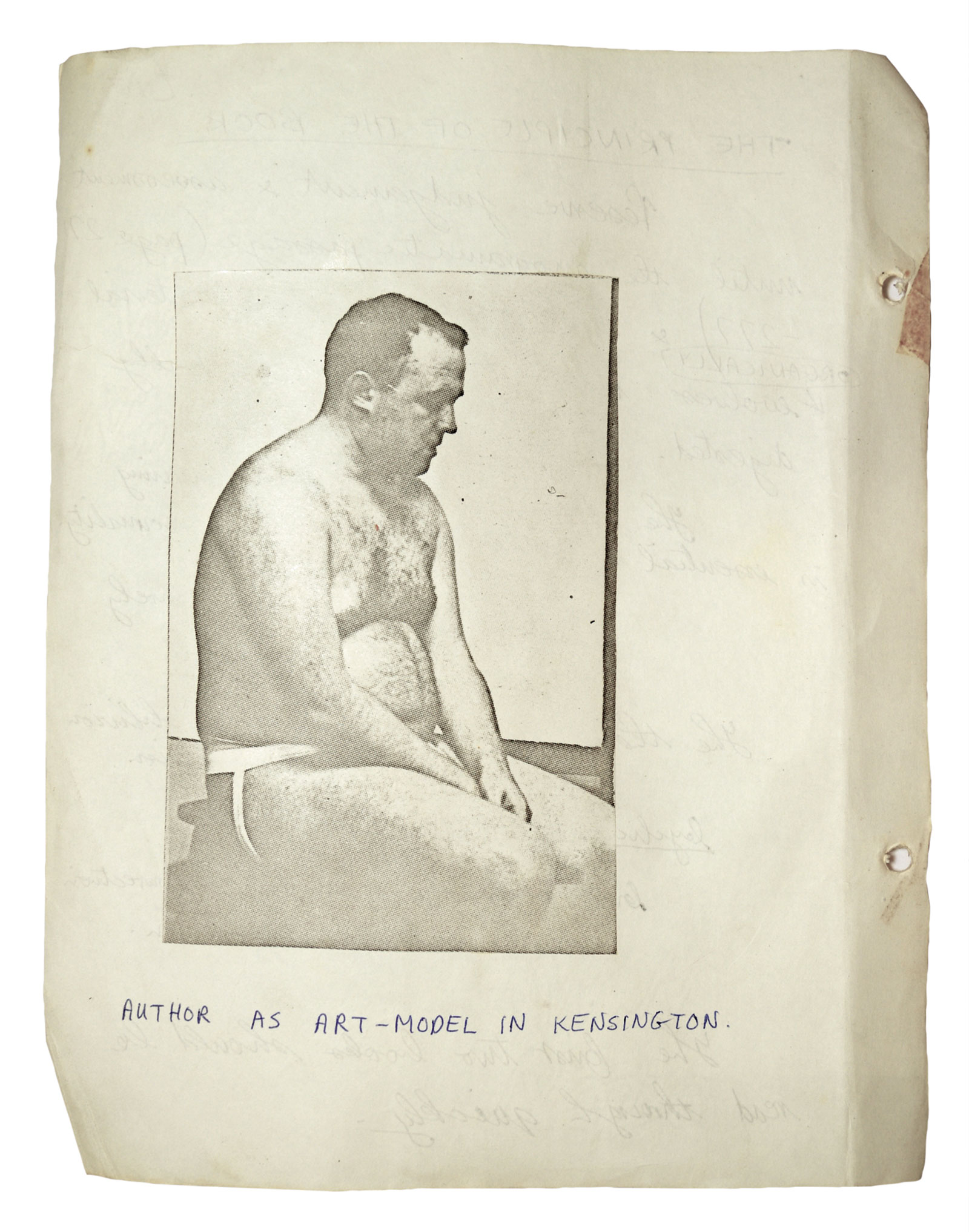

The same could be said of Clive R. Curtis, the unknown author of the unknown novel “Sparraw’s Kneecaps,” its first volume given the self-referential subtitle: “A Novel—totally nonfictional.” This manuscript has been manhandled and is moth-eaten, its type dirtied across different decades. Curling forward and back is the red front cover, repaired beyond recognition. The back cover has a hole in its heart. Scribbled above this rip is Clive Reginald Curtis’s London address written at a forty-five-degree angle: a mixture of looping letters and squared-off capitals. A torn monochrome page adhered to the manuscript’s middle repeats: FRAGILE PLEASE HANDLE WITH CARE.[2]

Marguerite Duras would have considered Clive’s manuscript, with its jagged spine and jagged syntax, an isolated body of what she called “virtual literature.” “Published literature,” she wrote, “represents only one percent of what is written in the world. It seems worthwhile to talk about the rest, an abyss, a black night out of which comes that ‘bizarre thing,’ literature, and into which almost all of it disappears again without a trace.”[3] “Sparraw’s Kneecaps” is a cryptic archival object and a novel in one. Locked into a latent state of anticipation, the object’s anonymity enables an imaginative reading, and writing, of gossip.

Clive’s novel is autobiography made fragile by the context of fiction. He cuts into the self and carves it, mixing confession with novelistic invention in spiraling, uncensored syntax. William Burroughs once told the poet-artist Jeff Nuttall that the way to make cut-ups was to “establish a schizophrenic relationship with a typewriter”[4]—a promise Clive attempts to fulfill. In this novel of “autobiographical anecdotes,” Clive looks to “smother [the page] with type” to “reach [his] aim of 55,000 words.” Word count hereby becomes an indication of lexical prowess, and morphemes are made numerical. Seemingly out-of-control, the writing multiplies itself; raw, atavistic, unclean—a merging of life and language. As Duras writes (in the book called Writing): “Writing comes like the wind. It’s made of ink, it’s the thing written, and it passes like nothing else passes in life, nothing more, except life itself.”[5]