Kiosk / Summer 2015

In the nooks and crannies

Cabinet

While preparing the report on our recent visit to our Andalusian outpost (see “Jubrique Update”), we were thrilled to receive an email from our friends at Lapham’s Quarterly inviting us to join them for “Coexistence of Cultures & Faiths: A Voyage to the Historic Cities of Morocco & Andalusia,” a twelve-day intellectual holiday cruise aboard the luxury ship L’Austral. The chance to return to southern Spain, this time while engaged in “open-ended conversation with some of the leading public intellectuals of our generation,” was, needless to say, enormously enticing. Alas, after outfitting the staff with the cravats and fountain pens appropriate to such an occasion, we found that Cabinet’s edutainment budget could no longer cover the $14,790 per person needed to participate in this adventure for “discerning travelers.” But all is not lost. Inspired by the Lapham model, Cabinet is pleased to announce that it too will stage a cruise of sorts this coming spring—“Barely Staying Afloat: An Aquatic-Intellectual Voyage up the Gowanus.” Stay tuned for more information.

• • •

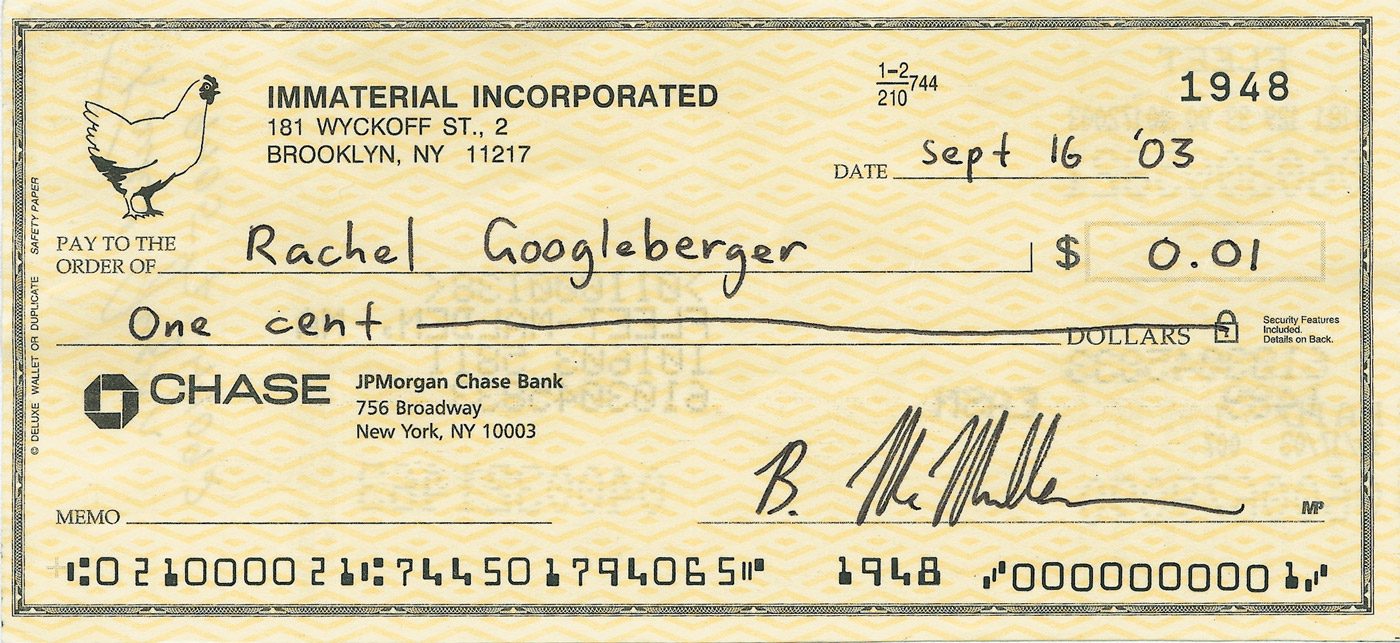

In addition to its obvious edificatory effects, our cruise will also hopefully serve as a fundraiser to help recover our losses from the fountain pen and cravat fiasco. However, we’ve also recently discovered an alternative fundraising strategy, namely, recashing previously cashed old checks. As ultra-veteran Cabinet readers may remember, in 2003 we met curator Rachel Gugelberger, whose improbably wonderful surname provided the occasion for us to issue her thirty checks—one a day, each in the amount of one cent, and each to an increasingly far-fetched misrendering of her family moniker (examples included Mrs. Web Utility Meat Sandwich, Emperor Ra’l Go’r, and May’Shel Kukenperker.) To our and Gugelberger’s surprise, her bank cashed twenty-eight of the thirty checks. (One was refused because we had forgotten to write out the amount, and one was lost by Gugelberger.). We printed the fronts and backs of all the cashed checks in Cabinet no. 14 and also featured them on our website.

Imagine our bewilderment when a recent bank statement showed check number 1948, dated 16 September 2003, as recently deposited. Although only one cent, this return of the repressed prevented us from balancing our books for that month. Had the bank made an error? Had Gugelberger fallen on such hard times that upon discovering the long-lost check in some drawer she had decided to get her penny’s worth? A quick glance at the old issue confirmed that the check in question had in fact long since been cashed, and as old-timers will remember, cashed checks in 2003 were physically returned to the issuer, which meant that the original check could not have been recashed, accidentally or otherwise. By looking online at our bank’s scan of the front and back of the recashed check, it became clear that someone had in fact used the new-fangled “mobile deposit” option to redeposit a facsimile of the original check created by scanning its front from the magazine or our website, and pairing it with the pristine back of an unrelated check, which s/he then endorsed. As we go to press, we are reconciled to the prank (which is in the spirit of the original) but our books remain unreconciled. Our bank is eager to open an investigation because such an action, even if it concerns a negligible sum, nevertheless constitutes forgery of a financial instrument protected by federal law. We are not keen to follow our bank’s advice. Although this has added to our administrative workload this month, we also have some admiration for the stunt in that it carries an element of genuine risk as well as demonstrating a certain level of artistry. A warning! We are old-fashioned and admire originality; anyone who copies this caper can expect a visit from the bunco squad.

• • •

The obvious criminal elements in our readership put us in mind of a recent discussion that occupied a good part of an afternoon here. While editing Jerry Toner’s article, we learned that thieves in the Roman Empire were punished on a graduated scale of guilt based on whether or not they had been “caught in the act,” a concept in Roman law that was largely a matter of proximity to the scene of the crime. Roman lawyers apparently could not agree what exactly the spatial parameters for “catching someone in the act” were. Ten feet from the victim’s house? A hundred? As is often the case, we moderns first enjoyed a snicker at an archaic practice, one that apparently could not systematically establish at what distance from a crime one could be said to still be “caught in the act.” And then we realized that we also have absolutely no idea what this apparently very familiar concept means in practice. If a criminal is in your apartment stealing your cravat and fountain pen and is interrupted by the police, we would certainly say that he has been caught in the act. Is the act over the minute he has left your private property? It would seem safe to say that the act has concluded when he has returned to his own apartment and stashed the loot for his spring trip to Andalusia and Morocco. If apprehended there, we would not say that he had been caught in the act, even if his apartment were next door to yours. But what if he lives in a different neighborhood; is he caught in the act if he is apprehended walking back to his home a mile away? Or does the thief in fact decide when the act is concluded? A nervous criminal might still feel himself to be “in the act” halfway across town, whereas the very cool customer might even celebrate at your neighborhood bar, content in the knowledge that the deed is done. The question finally lies at the intersection of spatial, temporal, and psychological considerations that give us new respect for the conundrum with which our Roman friends also wrestled.

• • •

While researching this issue, we read a terrific article written by Ron Rosenbaum in 1971 on “phreaking,” all the ways in which the US phone system could at that time be manipulated using various sounds. It included this quote from a dealer who is selling phreaking devices to the Mafia:

I wouldn’t mind seeing them [the Bell telephone company] screwed. A telephone isn’t private anymore. … And you know what else. You don’t hear silences on the phone anymore. They’ve got this time-sharing thing on long-distance lines where you make a pause and they snip out that piece of time and use it to carry part of somebody else’s conversation. Instead of a pause, where somebody’s maybe breathing or sighing, you get this blank hole and you only start hearing again when someone says a word and even the beginning of the word is clipped off. Silences don’t count—you’re paying for them, but they take them away from you. It’s not cool to talk, and you can’t hear someone when they don’t talk. What the hell good is the phone? I wouldn’t mind seeing them totally screwed.

Makes one nostalgic for the days when one could be nostalgic that human silences were being stolen and replaced by automated machine silences.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.