Inventory / Motoring While Black

On the road with the Green Book in Jim Crow America

Julian Lucas

“Inventory” is a column that examines or presents a list, catalogue, or register.

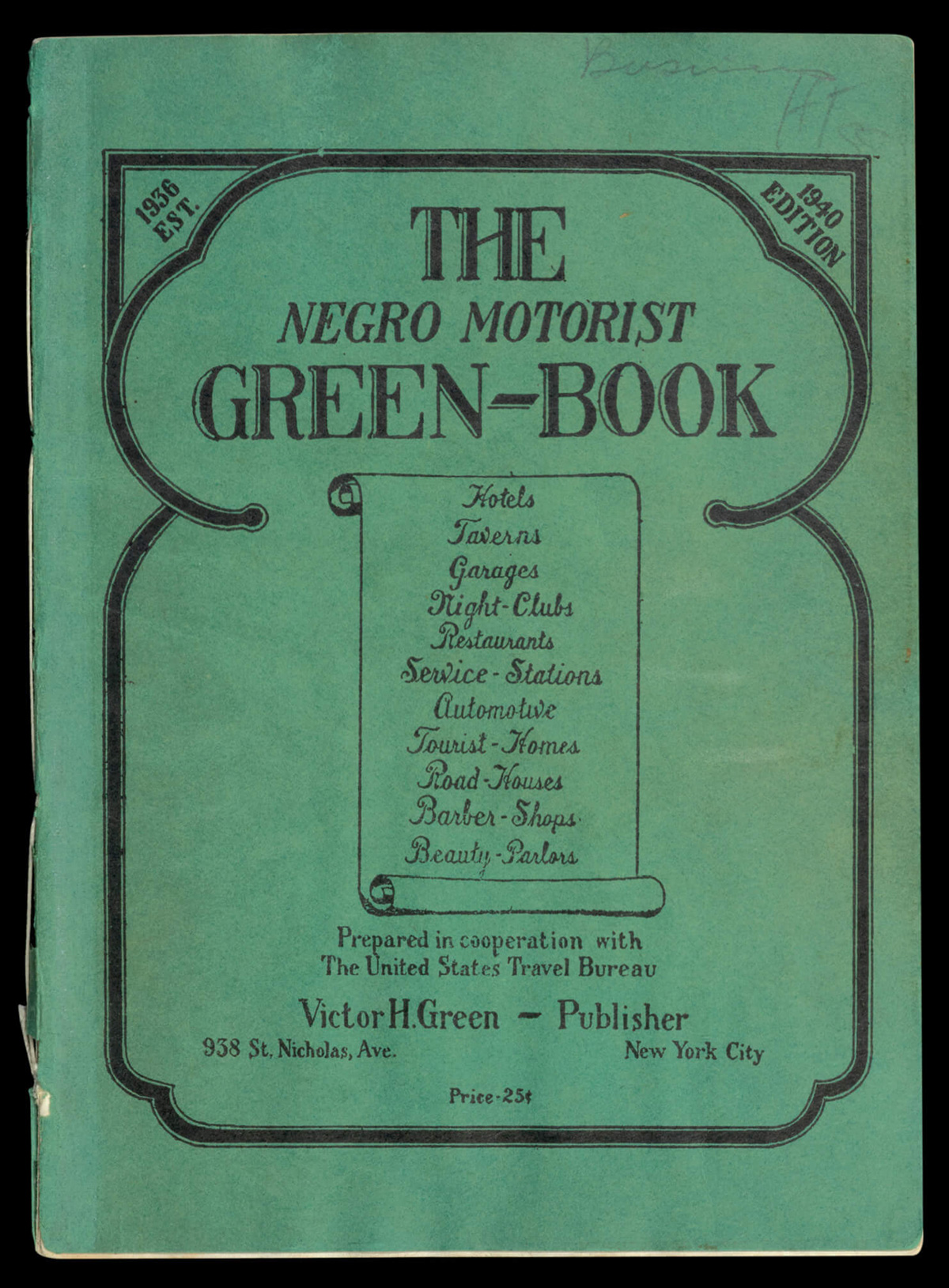

When The Negro Motorist Green Book was first published in 1936, it was a slim pamphlet listing those hotels, restaurants, garages, and other businesses in New York City where black travelers could be sure of good service and equitable treatment. This was not the case at every establishment; the New York of the day could be as discriminatory, even as dangerous, as the segregated South. But the guide’s publisher, Victor H. Green, was an experienced provider of safe, reliable transit. He was a letter carrier for the postal service, whose unofficial motto—inscribed over the doors of the Farley building in Manhattan—proclaims its commitment to freedom of movement: “Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds.”

Nor would discrimination stay Green’s “Negro Motorists.” Inspired by Green’s own brushes with racism, and modeled after similar guides in the Jewish press, the Green Book offered black travelers “assured protection.” It was sold at gas stations for a quarter, and became so immediately popular that Green rented an office, hired a staff, and published an expanded second edition, which included listings for as much of the country as he and his part-time agents could cover. Readers quickly began to consider the guide an important component of black civil society: “We earnestly believe ‘The Negro Motorist Green Book’ will mean as much if not more to us as the A.A.A. means to the white race,” one subscriber wrote in.

The editors had aims as high as their reader’s expectations. The guide they wanted to publish would be not only an almanac of racial prejudice, but in their words, “something authentic to travel by”—a promise that you and your family would never go bedless in Bethlehem, however far afield. The Green Book would also serve as an optimistic window on what W. E. B. Du Bois called the nation within a nation: a parallel world of black businesses, colleges, community organizations, and social networks, all of which seemed, to some, a promise of broader transformations. Between listings, the Green Book’s editors printed dispatches from this other world: portraits of black excellence that suggested, however vaguely, that equality would soon come. Some were inspirational biographies, like the 1939 edition’s sketch of one of the guide’s patrons, James A. Jackson, who began his career as a bellboy and minstrel performer before becoming a marketing specialist for Standard Oil. Others were travel essays, noting such things as the “many beautiful homes” owned by black residents of Greenville, South Carolina; the prosperity of the majority-black town of Robbins, Illinois; or the cigar-chomping panache of a black captain, employed as a pilot on a Sea Islands steamer.