Sentences / Fair Hopes of Ending All

The morbid extravagance of John Donne

Brian Dillon

“Sentences” is a new column by Brian Dillon each installment of which examines the mechanics and style of a single sentence chosen by the author.

Wee have a winding sheete in our Mothers wombe, which growes with us from our conception, and wee come into the world, wound up in that winding sheet, for wee come to seeke a grave; And as prisoners discharg’d of actions may lye for fees; so when the wombe hath discharg’d us, yet we are bound to it by cordes of flesh, by such a string as that wee cannot goe thence, nor stay there.

—John Donne

The poet and preacher John Donne died from stomach cancer in the spring of 1631. He had likely been sick for a year, but continued in his office of dean at St. Paul’s cathedral, where his weekly sermons were admired for their erudition, piety, and extremes of metaphorical invention. When illness made him quit the capital for his daughter’s house in Essex, rumors arose that Donne was already dead, or was feigning his distemper. Gathering his strength, he returned to London in March, quite sensible of his hourly decline but resolved to deliver a last sermon, at the palace of Whitehall before King Charles I and his court. As Donne’s first biographer Izaak Walton tells us, the poet’s friends were appalled at his appearance—he had left about him “but so much flesh as did only cover his bones”—and they tried to dissuade him from his homiletic duty. When he rose as appointed on the first day of Lent and in a hollow voice began to speak of dissolution, decay, and the life to come, it seemed to them that he had composed his own funeral oration.

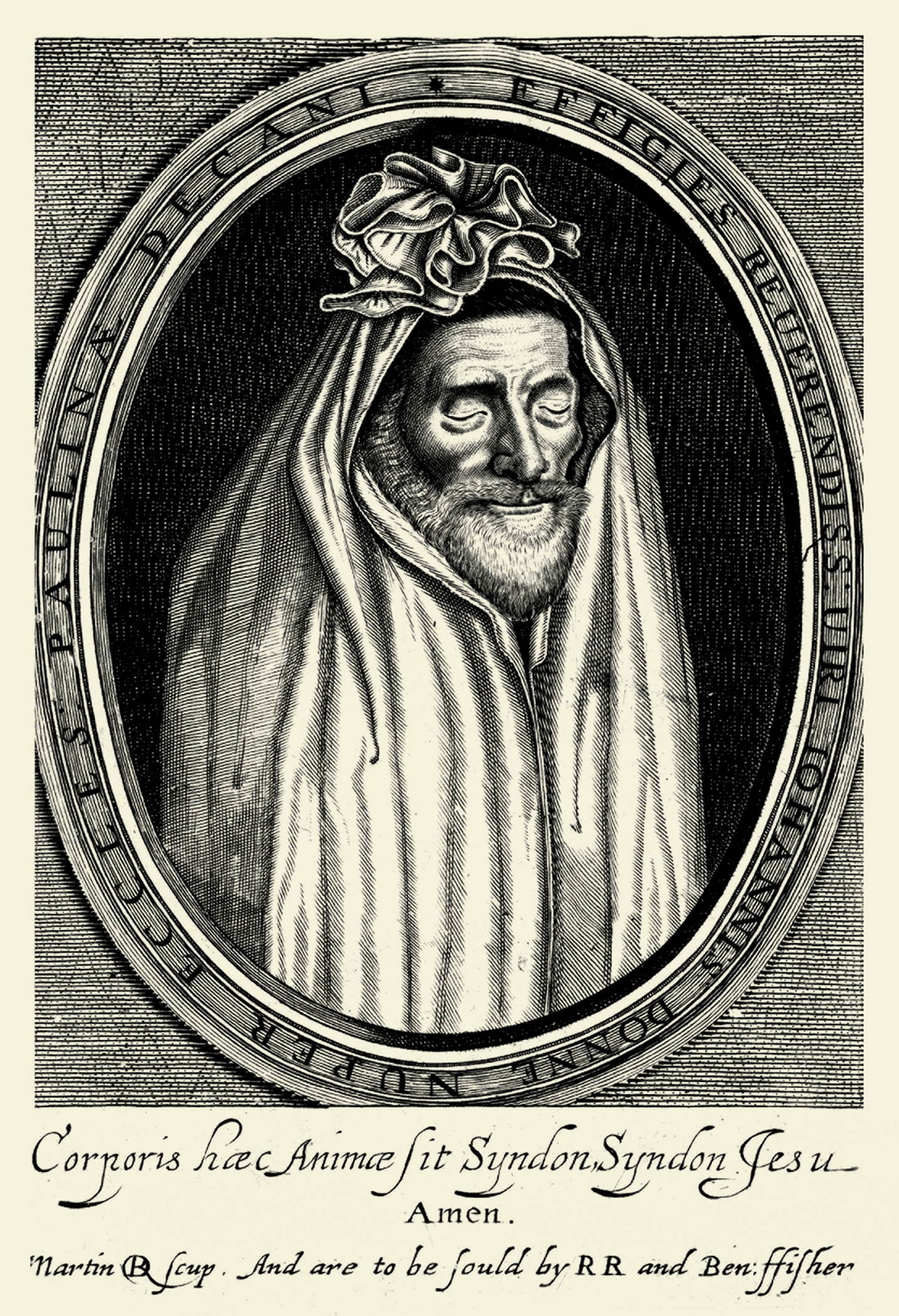

Such was Donne’s devout insouciance in the face of death that in the days before he spoke this sermon—and in it the astonishing sentence that is today’s lesson—he contrived its visual counterpart, his own ghastly monument. He summoned a painter to his sickroom, who found the learned dean shrouded head to foot, his eyes closed and limbs arranged as if already in the grave. Donne had the resulting portrait set by his bedside so he could look upon it in his last days—as the critic Frank Kermode put it, the dying man seemed possessed of an “almost histrionic composure.” It was on this picture (now lost) that the sculptor Nicholas Stone based the monument to Donne that still stands in St. Paul’s. An engraving from the same source formed the frontispiece to the final sermon when it was published in 1632: here is the ailing divine embarked on his ultimate spiritual migration, oblivious to the world of flesh even as he makes us stare at its grisly remnant.

In print, the sermon is called “Deaths Duell,” though Donne never titled his sermons: nothing came before the biblical quotation that gave each one its subject and its structure. In this case the lesson is from Psalm 68, verse 20: “And unto God the Lord belong the issues of death.” As was sermonic convention, Donne approaches this ambiguous line via an explicit tripartite plan. His task as preacher is, first, closely to read this text for its diverse meanings; second, to set it in the context of biblical and theological authority; third, to lay out nakedly, in a kind of moral anatomy, the lessons and models that may be taken away. “Deaths Duell” begins with another triad: a somewhat distracting architectural conceit by which Donne thinks of the psalmic text as a building, with foundations, buttresses, and joints or “contignations.” But we are soon amid the fundamental truths of the text, of which there are also three. “And unto God the Lord belong the issues of death” means: He will deliver us from death, to eternal life; in death, because he will save us from undue suffering; and by death, for this trial is necess