Grave Matters

Tomb theft in ancient Egypt

Maria Golia

Egypt is almost entirely desert; unless you happen to be somewhere in the central Nile Delta or Fayoum Oasis, it is never more than five kilometers away. The desert encouraged the sociability that characterizes Cairo, a city whose population has historically been concentrated as far away from it (and as close to the Nile) as possible. Only recently and with great reluctance have people begun to inhabit the outlying wastelands in significant numbers. Describing how “nature and climate affect the psyche of human groups,” Egyptian social commentator Milad Hanna remarked that “the desert, with its infinite space, stimulates imagination and awakens fear of the approaching stranger.”[1] The residential apartment blocks sprouting in Cairo’s environs in fact stand shoulder to shoulder, huddled together as if for company. Surrounded by desert, Cairenes have lived in tight quarters for so long they’ve become agoraphobic.

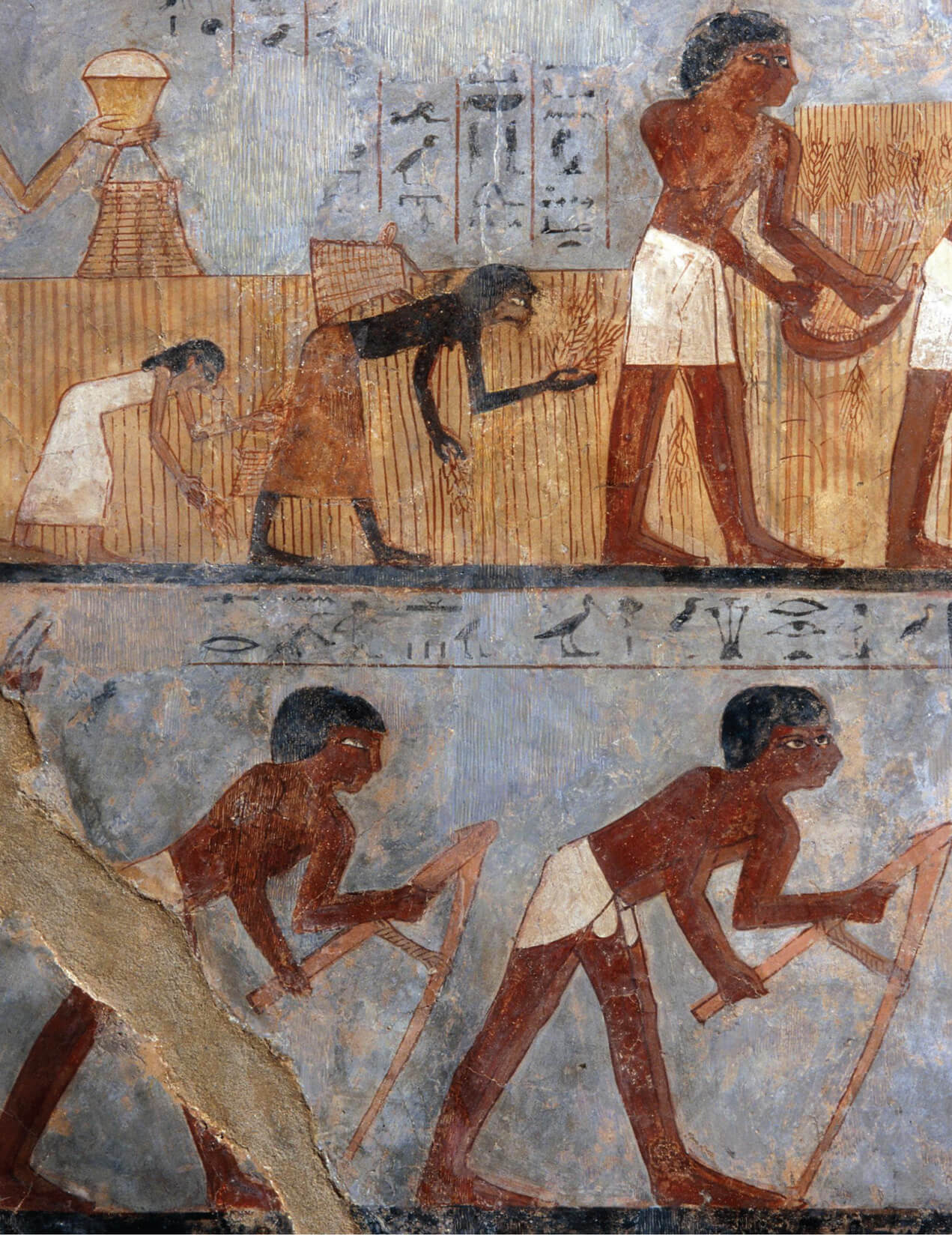

Egyptians have long associated the desert with the strange and threatening. Although it was predominately desert in antiquity, Egypt was not as arid as it is now. The Nile delta was a marshland, labyrinthine groves of papyrus with tall, slender stalks and fan-like feathery tips. The river roiled with fish; fowl were so plentiful they were hunted with nets strung up between the five-meter-high papyri stems. The land flanking the river was carpeted with fields and the annual floods more or less guaranteed at least one big crop of grains, in addition to pulses, roots, vegetables, and fodder enough for a variety of domesticated animals. The river was understood as a godsend, an affirmation of divine will, yet at just an hour’s walk from its banks, this verdant, animated realm came to an abrupt halt. At the edge of the floodplain lay an endless expanse of scorched hills and valleys. The desert was everywhere at the corner of one’s eye: vast, empty, and silent, the negation of life, nature at its most fiercely indifferent. Cemeteries were always located there, west of the Nile where the sun set, the place of death. Like other natural phenomena observed by the ancient Egyptians, the desert was associated with a deity, in this case Seth, god of strangers and strange lands.

Son of Geb (father earth) and Nut (mother sky), Seth and his siblings Isis, Osiris, and Nephthys belonged to the Great Ennead, a group of A-list gods, but he was the family rogue. Lord of the tempest, he could raise the sand-laden winds that blocked the sun (the eye of Ra, the original god) and the rainsqualls that sent destructive streams of muck and rubble roaring down from the desert hills. Cold-blooded lizards that thrive on heat were said to be ruled by Seth, as were deadly scorpions who love the dark. Crocodiles and hippopotami, which were plentiful in the Early Dynastic Period (ca. 3000–2686 BC), were Seth’s havoc-wreaking helpers. Seth himself was depicted as a man with the head of an unidentifiable, perhaps mythical or extinct, animal. In hieroglyphic writing, the Seth-animal was used in words such as illness, crisis, nightmare, rage, tumult, to boast, to be harsh, to roar, and to deceive. The figure was likewise used in hieroglyphic writing to designate “confusion,” the opposite of order.[2]