Ingestion / The White Rabbit and His Colorful Tricks

Breakfast cereal, dietary purity, and race

Catherine Keyser

“Ingestion” is a column that explores food within a framework informed by aesthetics, history, and philosophy.

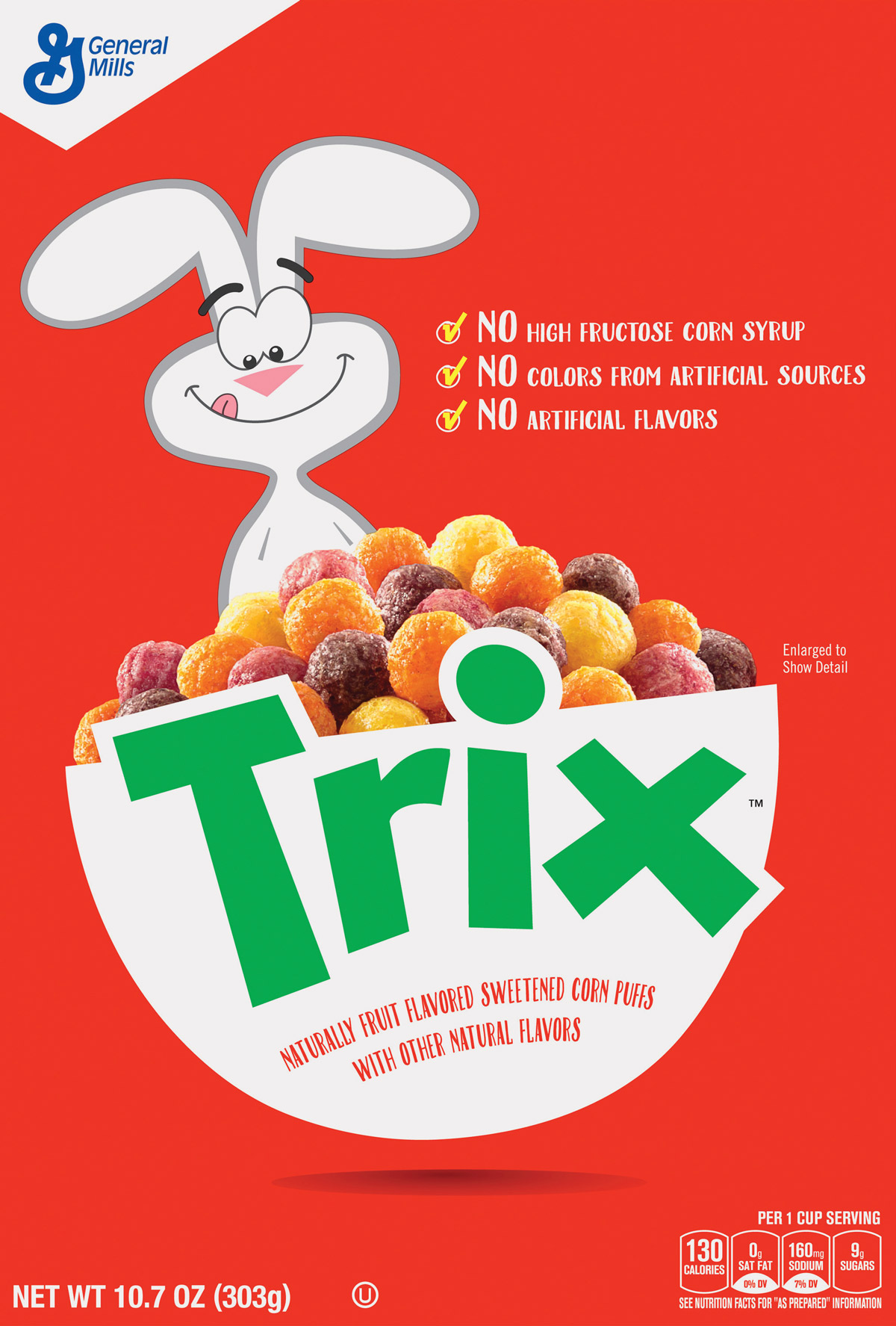

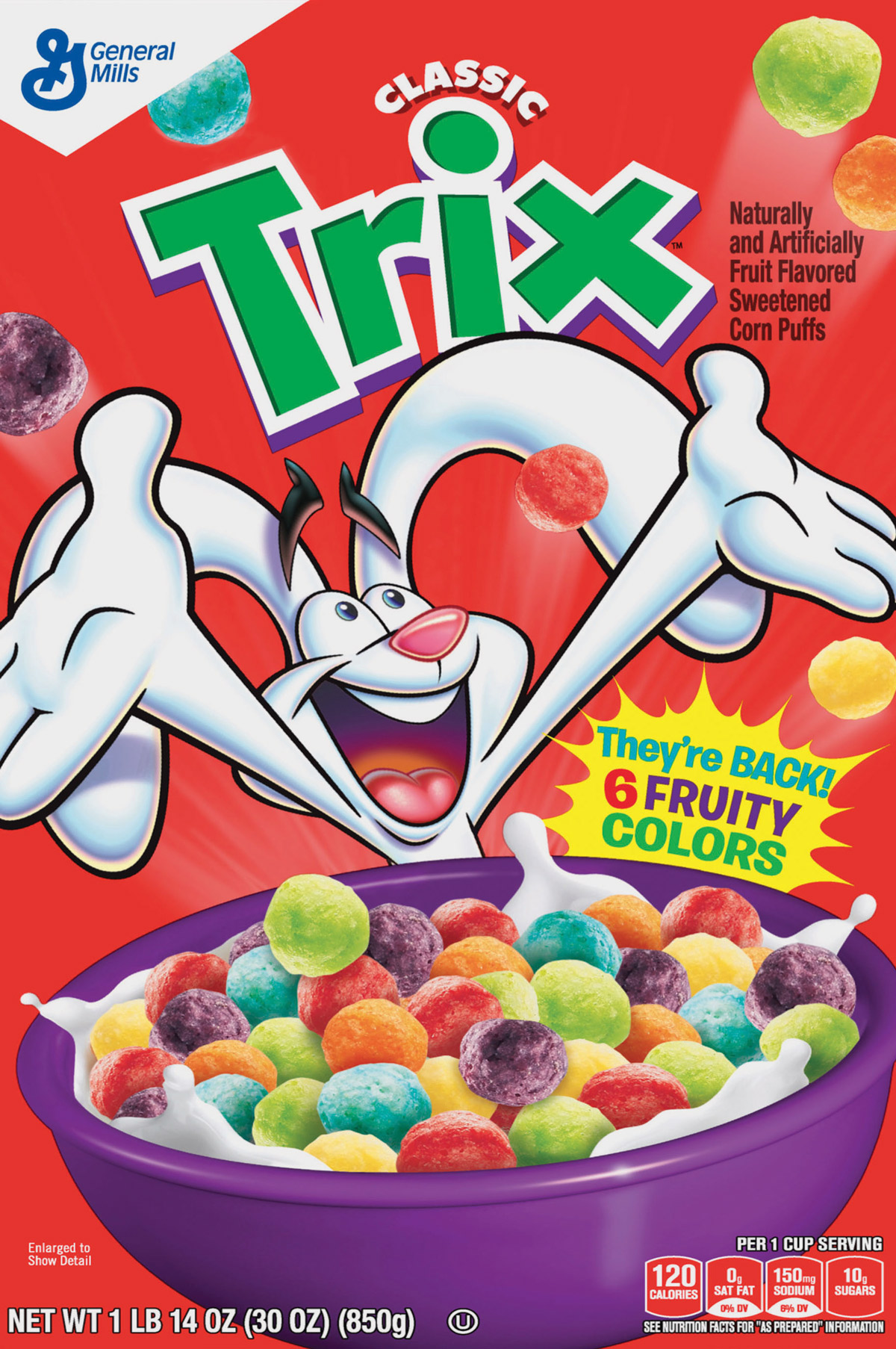

In 2015, General Mills reformulated Trix with “natural” colors. Customers complained that the bright hues of their childhood cereal were now dull yellows and purples. Two years later, the company released Classic Trix to stand on store shelves alongside so-called No, No, No Trix, the natural version. This nickname, promising “no tricks,” sounds abstemious; the virtuous customer says no to technicolor temptation. But Trix customers wanted their colors back. As one Tweet put it: “I mean, I get that artificial flavors are bad and all that shiz, but man I miss neon colored Trix.”

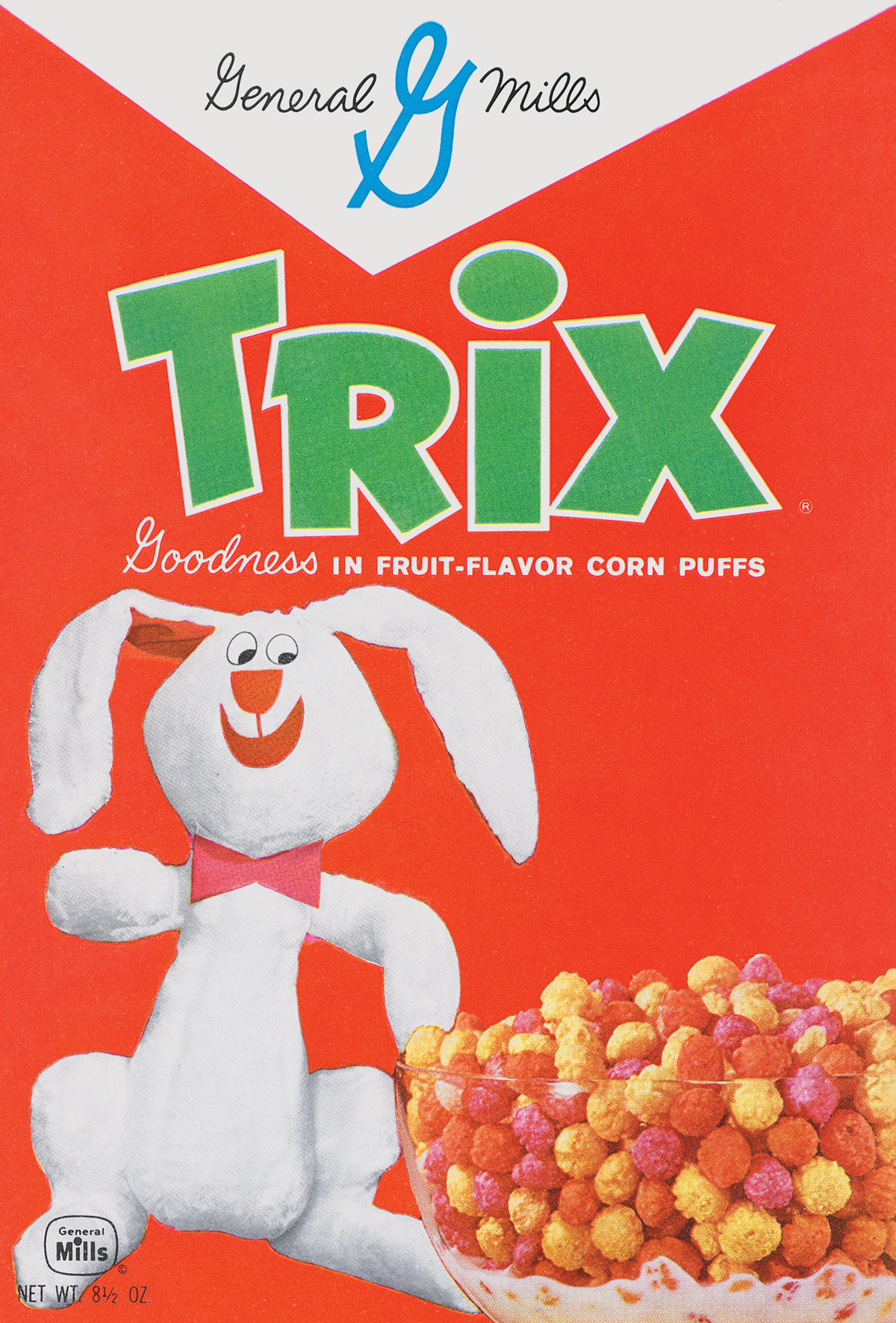

What can (or should) the scholar of American culture make of this desire for color? Bright foods are in some sense an invention of a modern food industry that uses dye to intensify visual aesthetics. They also, however, evoke the tropics, brilliant fruits like bananas and oranges that became more broadly available in the United States in the early twentieth century thanks to corporate imperialism and cold storage. Though its colors came from industrial dyes, General Mills hoped to associate Trix with this tropical paradise. When Trix cereal was first released in 1954, advertisements trumpeted its “bright fruit-colors!” and personified its colorful puffs as though they were eager to be eaten: “Gay little sugared corn puffs in a happy mixture of colors—red, yellow, orange. Fun to see! A joy to eat!” Color itself promised to communicate pleasure.

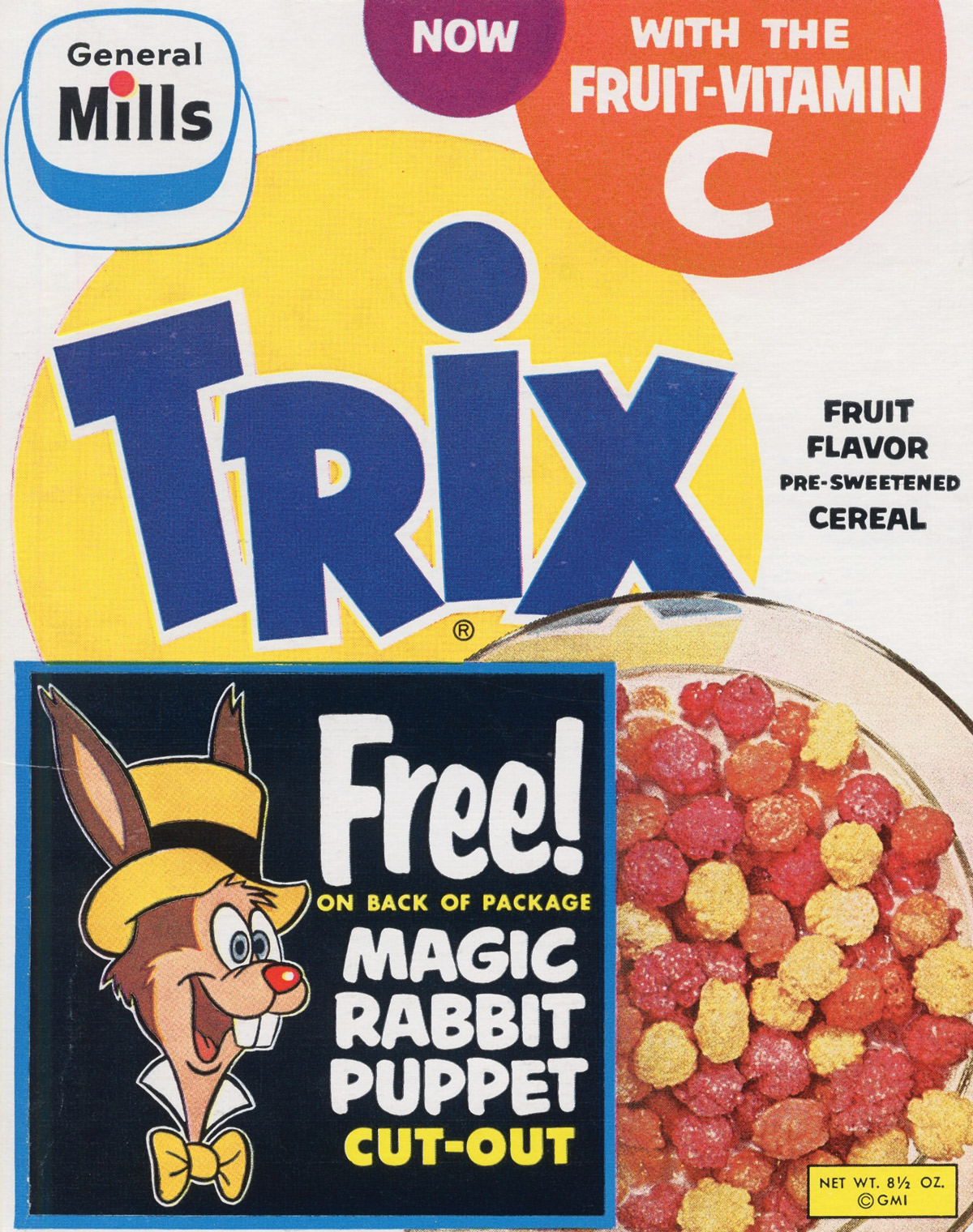

This association between color and gaiety has a long racial history in the United States and in the food industry in particular. Miss Chiquita Banana trilled a captivating song, while the mischief-maker Brer Rabbit struck a dapper figure on a molasses company’s products with his yellow bow-tie and matching trousers. Suggestively, this same character, who had recently starred in Walt Disney’s Song of the South (1946), was the first in a long line of rabbits to be featured on the Trix box, appearing in a campaign designed to promote the mid-1950s re-release of the film. In the Disney movie, Brer Rabbit wears a bright pink shirt and speaks in black dialect. And beginning in 1958, Trix used an image of a grinning brown bunny dressed in the classic minstrel show ensemble of an oversized top hat and white gloves to promote the product. His hat is yellow, and his nose is bright red, the very colors featured in the fruit-flavored cereal.

Brer Rabbit was made famous by Joel Chandler Harris’s popular Uncle Remus stories, dialect tales published in the years following Reconstruction that generated nostalgia for the plantation South. Black folktales inspired these stories, but through them, Harris recast the plantation as a site of pleasure and abundance, uniting master and slave in happy harmony. The Uncle Remus tales were what scholars call local color fiction, imagining the pleasures of the preindustrial past and black oral traditions during a cultural moment of industrialization and expanding print culture. The black storyteller and his folksy, comic dialect opposed threats of mechanization and standardization. In Love and Theft, Eric Lott suggests that white working-class men were drawn to minstrelsy because blackface allowed bodily excesses and pleasures increasingly unavailable under the industrial regime of uniformity and discipline. Lott’s thesis helps to explain the popularity of Brer Rabbit for industrial food brands. His trickster persona promised unrestrained pleasures for all consumers, white or black, while his supposedly Southern and black roots disguised the impersonality of packaged food with the aura of authenticity.

This dynamic of commodified desire—which bell hooks memorably describes as “eating the other”—sheds new light on Trix’s advertising strategy. The standard setup of a Trix commercial from the 1950s through the 1980s involves the white rabbit’s envy of children who get to eat colorful breakfast cereals. (In the 1950s, the children are white-skinned cartoons. By the time of the live-action commercials of the 1970s, at least one of the children is recognizably black.) The Trix rabbit attempts to steal the cereal, only to be consistently foiled by the sharp-eyed children. These attempted thefts resemble the paradigmatic Brer Rabbit story described by Bryan Wagner in Tar Baby: A Global History. Harris dropped the prehistory of the conflict between the rabbit and the fox, jumping right in to their apparently natural enmity, but other versions, including William Owens’s “Folk-Lore of the Southern Negroes” (1877) which inspired Harris’s retelling, explain the argument as a struggle over resources. A property owner, variously cast as a fox or a wolf, defends his food, water, or whiskey from an importuning and tricky rabbit. In the Trix commercial, the child plays this role: “Silly rabbit, Trix are for kids.”

Bottom: An early ancestor of the iconic Trix rabbit, ca. 1961. Courtesy General Mills Archives

The Trix rabbit is not only Brer Rabbit’s trickster heir, however, as his coat color has been significantly adjusted from that folkloric figure who “represents the colored man,” according to Abigail Christensen in Afro-American Folk Lore (1892). The Trix rabbit also recalls Lewis Carroll’s White Rabbit, who unwittingly leads Alice into Wonderland by “pop[ping] down a large rabbit-hole under the hedge.” Some critics have associated the tunnel Alice enters with the digestive tract. In Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1853), the little girl quaffs beverages labeled “Drink Me” and nibbles cakes labeled “Eat Me”—perhaps naively reassured by the fact that neither reads “poison.” She even gnaws at the hookah-smoking caterpillar’s mushroom. These alimentary adventures suggest how far ingestion—and intoxication—transforms our bodies and minds, and Carroll celebrates rather than condemns this susceptibility. In Carroll’s novel, imperial goods—whether tea, treacle, or opium—open up new and exciting doors in Alice’s imagination.

These two rabbits, Brer Rabbit and the White Rabbit, are characterized quite differently. Brer Rabbit is an audacious trickster, telling fluent lies and tackling grand schemes. The White Rabbit is anxious and proper, late for important commitments and annoyed with the servant-girl for her failure to bring him his gloves. The Trix rabbit combines these two personae—attempting masquerade and deception to accomplish his impossible dream, but also, especially in his earliest incarnations, seeing himself as a humdrum carrot-eater who couldn’t possibly attain the forbidden pleasures of childhood.

The white rabbit in a 1959 Trix television commercial sounds like a nebbishy middle-aged man. Holding the Trix box, he smiles, leaps, and flutters his feet, but then, with drooping ears, he recalls his melancholy lot in life: “That’s my problem—Trix are for kids.” In a 1960 commercial, the rabbit acquires thick eyebrows like Groucho Marx, and voice actor Mort Marshall sings: “Those crispy Trix fruit colors make me a happy fellow. There’s raspberry red, orange orange, and luscious lemon yellow.” During this song sequence, the rabbit prances balletically across the screen. When the boy takes back his box of Trix, the rabbit’s feet are planted squarely on the ground, and he chomps on his carrot like a cigar. In spite of his sweet tooth, the Trix rabbit must reluctantly give in to adulthood and restraint, maturity and midlife disappointment.

The little girl in the 1959 television commercial insists that when she grows up, she will stock her house with Trix. The viewer knows, however, that the children will grow up and will likely breakfast on blander fare, becoming the wholesome white subjects their cereal-buying parents envision. The white rabbit, by contrast, will not transform over time. His difference is fundamental: he will always be a rabbit, and hence he cannot enjoy the human treats. As Mel Chen puts it in Animacies, “categories of animality are not innocent of race.” Animacy hierarchies—which accord humans greater agency than animals—are often used to ballast racial divides and affirm white subjectivity. The rabbit’s inevitable failure consolidates the children’s humanity, implicitly identified with whiteness and consumerism. The Trix rabbit tries to “pass”—dressing as an astronaut, an old lady, a balloon vendor—but ultimately his difference is exposed. At the same time, his playacting seems more appealing than the children’s smug certainty about their cultural roles and consumer entitlement.

A hunger for recognition and a place at the table may be another legacy that Brer Rabbit has conferred to the Trix rabbit. Wagner argues that the Brer Rabbit fable confronts colonialism and food politics, insofar as the native rabbit attempts to withstand the predatory and territorial wolf. Trix commercials, developed in an era of Civil Rights protest, explore exclusion in a comic register. The question of which people could consume food and where played a major role in segregation, which led to famous lunch counter and soda fountain sit-ins. In this context, it is notable that in the 1959 television commercial, the Trix rabbit laments that he’s not allowed to go to school.

In the 1950s and 1960s, artificial color simultaneously represented exciting chemical pleasures and potentially contaminating dyes, which carried racial implications. Think of Violet Beauregard turning into a giant blueberry in Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964) after chewing Wonka’s experimental gum. The flavors are the best she’s ever tasted, but the results mark her body, leaving her skin permanently blue. The association between race, pleasure, and artificial color persists in contemporary culture. In Get Out (2017), Jordan Peele’s comedic horror film about white liberal racism, femme fatale Rose gobbles brightly colored Froot Loops while scrolling through pictures of black basketball players, trying to decide whom to prey upon next.

As this scene from Get Out underscores, the hunger for color often fuels its opposite, the strenuous celebration of whiteness as purported purity; as she eats her cereal, white-clad Rose sips a glass of milk with sinister self-satisfaction. In Ben Lerner’s novel 10:04, he writes of affluent white parents proud of their children’s natural diets:

It was the kind of exchange, although exchange isn’t really the word, with which I’d grown familiar, a new biopolitical vocabulary for expressing racial and class anxiety: instead of claiming brown and black people were biologically inferior, you claimed they were—for reasons you sympathized with, reasons that weren’t really their fault—compromised by the food and drink they ingested; all those artificial dyes had darkened them on the inside.

These narratives demonstrate the racist insidiousness of dietary purity, as the consumer carefully regulates ingestion in a process that Kyla Wazana Tompkins aptly calls the “anxious girding of the boundaries of whiteness.” As a cultural trope, artificial color exposes the fragility of whiteness and the impossibility of purity. Viewed in this light, it opens up imaginative possibilities for new forms of embodiment and interconnection.

Like the Trix rabbit rejecting his prescribed carrots to pursue a sweeter dream, we might rethink the cult of the natural in favor of a pleasure principle that admits our imperfect bodies and their enmeshment—for better and for worse—in global industry. “I have built my ship of death / aglow in sturdy chemicals,” Timothy Donnelly writes in his poem “Diet Mountain Dew”:

My mouth is full of you again …

A green like no other green …

… you are too

green for pasture, you are

my green oncoming vehicle,

usurper of green, assassin

to the grasshopper and its plan,

I put me in your path which is

the path a planet takes when it

means to destroy another I think

you know I’m O.K. with that.

A green like no other green

resplending in production since

1940 when brothers Barney

and Ally Hartman cooked it up

in Tennessee qua private

mixer named after moonshine,

its formula then revised by

Bill Bridgforth of the Tri-City

Beverage Corp in 1958 …

Artificial color makes visible the chemicals in which we are awash, but the effects of that industry and that toxicity are uneven. Packaged cereals are shelf-stable and low-cost, and their predictable presence in food deserts disproportionately impacts people of color. “So much of this toxic world,” Chen reminds us, “is encountered by so many of us as benign or only pleasurable.” Nostalgia for childhood Trix colors emphasizes the pleasures of the product’s bright colors over its chemical dangers in what might be hedonistic amnesia. But Chen asks us to acknowledge that toxins— which can be “addictive and pleasure-producing substances”—unite us even as they injure us, unite us in that very injury. Perhaps instead of abjuring these dyes—or pretending that doses of turmeric and achiote can restore us—we would do better to recognize our kinship with a “silly rabbit” who articulates our still-unsatisfied hunger.

Catherine Keyser teaches twentieth-century US literature at the University of South Carolina. She is the author of Playing Smart: New York Women Writers and Modern Magazine Culture (Rutgers University Press, 2010) and Artificial Color: Modern Food and Racial Fictions (Oxford University Press, forthcoming).

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.