Notes from the Attic

Displaying the material history of the CIA

Mahan Moalemi

“No single man makes history. History cannot be seen, just as one cannot see grass growing.” The CIA’s online Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room quotes Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago. The room features ninety-nine declassified documents, disclosed in 2014, that describe the agency’s covert program to facilitate the first publication, in 1958, of the novel in its original Russian. These documents appear on the website alongside millions of additional pages of material that will appeal to history buffs and UFO buffs alike.

Doctor Zhivago only appeared in Russian after English, French, Italian, and German translations had already earned it international esteem. The original, legendary samizdat has since been the object of intense study. But it was only in 2009 that journalist and broadcaster Ivan Tolstoy made allegations that the CIA had used the novel as an instrument of soft power by enabling Soviet citizens to read it. His book The Laundered Novel: Doctor Zhivago between the KGB and the CIA is crowded with claims and speculations, some of which we know, in hindsight, to be inaccurate, such as the suggestion that the agency influenced the Nobel Committee’s decision to award its literature prize to Pasternak, also in 1958.

The Zhivago example would make a perfect plotline for a classic pulp tale about the craft of intelligence, illustrating the shift from the hot, wartime climate of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in the early 1940s to the Cold War–era CIA. Procedures for the public disclosure of unreleased government records were instituted as a result of the bloody proxy wars in southeast Asia some two decades later, with the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) signed into law in 1966. The statute, which has since gone through numerous amendments and revisions, is still shot through with a comprehensive raft of exemptions. And with Executive Order 13526, issued in 2010, even information that meets the criteria for availability under FOIA can be exempted and reclassified upon reevaluation.

Taking one step back into the CIA’s sitemap, we arrive at the Library, where the earliest posts date back to April 2007, the year conspiracy theorists succeeded in their fifteen-year-long quest to declassify the “family jewels,” described by the agency as “almost 700 pages of responses from CIA employees to a 1973 directive from Director of Central Intelligence James Schlesinger asking them to report activities they thought might be inconsistent with the Agency’s charter.” On the day of their release, the then-director of the CIA, Michael Hayden, wryly stated that “most of it is unflattering, but it is CIA’s history.” Parts of this history had already leaked right onto the front page of the New York Times in 1974 when Seymour Hersh published his article on the “huge” project of domestic espionage against antiwar forces and other dissidents.

Back on the website, another Library subpage leads to the Center for the Study of Intelligence (CSI), a CIA department researching the agency’s very own history, along with methodologies of the intelligence field at large. The department publishes Studies in Intelligence, a peer-reviewed periodical founded in 1955 and containing both classified and unclassified content. Sourcing material for this journal is greatly facilitated by the department’s main mandate: administering the CIA Museum.

Founded in 1972, and occupying three corridors in two buildings at CIA Headquarters in Langley, Virginia, the museum is not open to the public. Access is granted only to the staff, official visitors, and those occasional reporters who succeed in obtaining security clearance. Toni Hiley, the museum’s curator for the past fifteen years, directs the “collection, preservation, documentation and exhibition of intelligence artifacts, culture and history”—as well as the Fine Arts Commission program, which has been running since the 1960s—to “bring the agency’s history to life.” The eight hundred exhibits on display range from art works and archival prints to weapons, espionage machinery, insignia, fake film scripts, and even boot hooks belonging to William J. Donovan, the “Father of Central Intelligence” and the founder of the OSS. That is only the tip of the twenty-eight thousand items sealed in this vast collection, drawing on which the museum frequently develops exhibitions, mounted off-site in partnership with other institutions in order to “promote a wider understanding of the craft of intelligence and its role in the American experience,” again according to the website.

More than two hundred of these artifacts are highlighted online, accompanied by concise, often enigmatic and tight-lipped, captions and embedded in a framework of multifarious tags, categories, stories, and dates; some of these items are also linked to the agency’s YouTube channel for a more dynamic follow-up. Branded as a chance to “Experience the Collection” online, the experience is more comparable to an infinite feed of disclaimers. “We can neither confirm nor deny that this is our first tweet,” posted @CIA on 6 June 2014, at 10:49 am, shortly after signing up. A catchy and effective PR manoeuver, indeed—and the agency has since been regularly embedding links to an “Artifact of the Week.” Similarly, the official Flickr profile dates back to 2011, and holds an album titled “All CIA Museum Artifacts,” though it contains only 168 images in total.

However, a huge pool of captioned stuff cannot readily amount to a perceptible sense of history. In 2014–2015, CSI published a guide to the CIA Museum and its collection, a companion to all the mediating anecdotes and interactive interfaces. In its preface, A Curator’s Pocket History of the CIA notes: “History can be studied in more than one way. … Museums are where you discover history by studying things, that is, artifacts, in context. … We start with what we have in the collection and use artifacts to reconstruct the history of the Agency. The result is more impressionistic and less linear than other histories.”

The Pocket History is apparently the first in a series of publications titled Notes from Our Attic, which “tells the story of the CIA through artifacts illuminating history in a way words cannot alone.” The attic turns out to be a particularly apt space to invoke for such a project. In the mid-1600s, the term began to be used to refer to an element of the classical façade—a low decorative wall right above the main cornice at the top of the entablature. By late eighteenth century, attic came to mean the interior space enclosed by such a structure; only then did the attic, that spooky room right below the roof, come into being. This move from an architectural order related only to the surface of a building to a repurposed, functional space behind the surface seems comparable to certain tropes of clandestine activity, where things are instrumentalized beyond their manifest appearance, as if an unprecedented space has been opened up behind their obvious skin, a space filled up with covert functions. Repurposed things have itchy skins, hence the utility of persistently scratching their surfaces to expose hidden intentions. The Pocket History is a guide to the question of how alternate, covert spaces are produced beneath the surface of ordinary objects when they are repurposed. But it is also a guide to the question of when, to the historical timing of these subterfuges and of their public disclosure. And moreover, it is an apologia for the why, often flaunting the logic of the ends justifying the means.

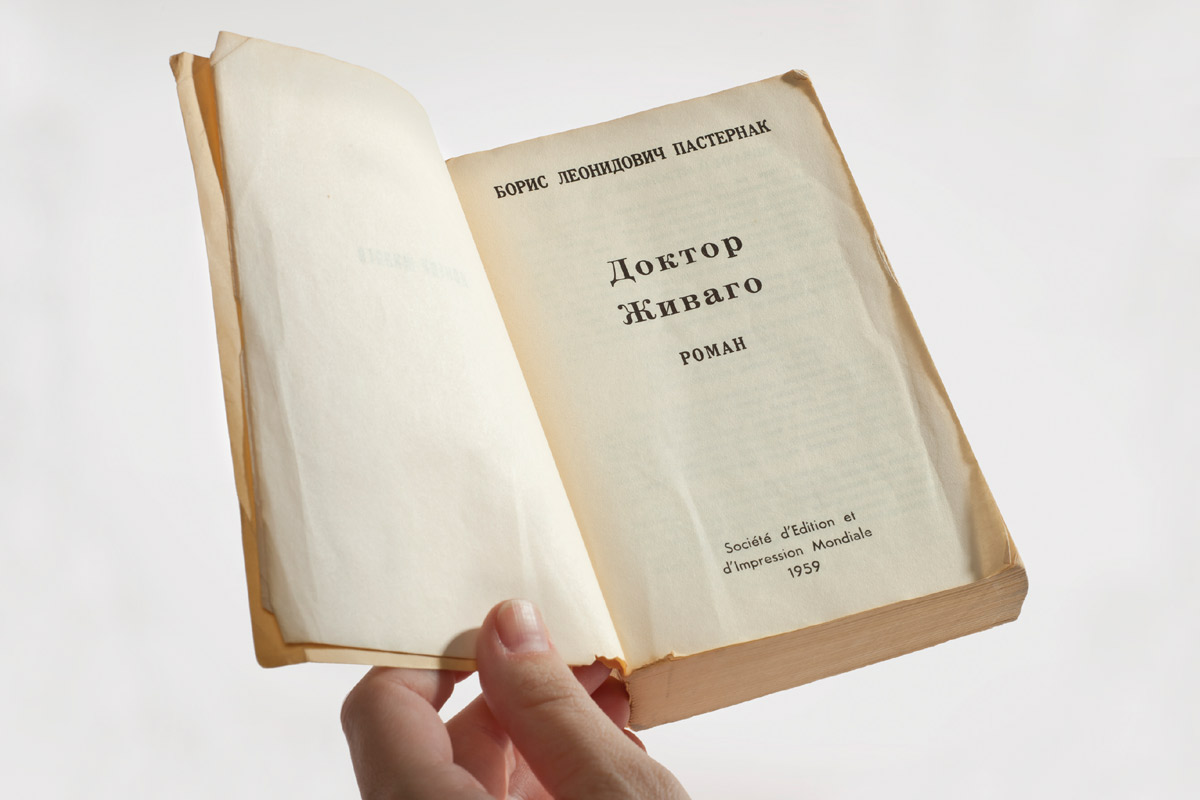

Well chronicled in the Pocket History is how it took only a few decades to go from Secretary of State Henry Stimson shutting down the US Army’s “Cipher Bureau” in the 1920s because it was wrong for “gentlemen” to “read each other’s mail,” to the Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) Allen Dulles declaring in the 1950s that “when the fate of a nation and the lives of its soldiers are at stake, gentlemen do read each other’s mail.” An image of a vest-pocket paperback copy of the Russian edition of Doctor Zhivago, published during Dulles’s tenure as director, is featured in the Pocket History, with the caption sternly quoting from Tolstoy’s book: “Pasternak’s novel became a tool that was used by the United States to teach the Soviet Union a lesson.” Expressing no direct endorsement or objection in the face of this allegation, the caption ends by simply noting the official declassification of related activities in 2014.

There is much retrofuturistic technology to be discovered in the collection. There might be a miniature camera hidden behind a brooch or button, or a bird for that matter. The Pigeon Camera, devised by the Office of Research and Development (ORD), was used during the still-undisclosed “pigeon missions.” It was small and light enough to be carried by the bird, which flies much lower than a satellite or an aircraft, and delivers more detail than other “imagery collection platforms.” Another initiative of the ORD was the Insectothopter, an eavesdropping Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) in the shape of a life-sized dragonfly. Robot Fish “Charlie,” on the other hand, was an Unmanned Underwater Vehicle (UUV) developed by the Office of Advanced Technologies and Programs. Equipped with certain communication and propulsion systems and remotely controlled, such aquatic exploration too was aimed at perceiving more and more terrains of nature as bearers of intelligence.

But the more modest examples also look more cunning. Take the pair of gold cufflinks that DCI Richard Helms presented to case officer George Kisevalter upon his retirement in 1970. Embossed with the Pallas Athena helmet and a small sword, it was one of two identical pairs designed by the Chief of Station Peer de Silva, a graduate of the United States Military Academy, after his alma mater’s “Duty, Honor, Country” crest. The other pair belonged to Pyotr Popov, a major in the Soviet Military Intelligence (GRU), codenamed ATTIC. Stationed in Vienna and then in East Berlin, Popov wore the cufflinks from 1953 to 1959, always looking for the other pair—worn by an assignee allocated by Kisevalter, his handler—in order to confirm a bona fide connection with the CIA.

Categorized as Bodyworn Surveillance Equipment, the dress code for clandestine activity is “inconspicuous.” The artisans, technicians, and engineers working at the Office of Technical Readiness (OTR) make sure that all accessories and clothing are carefully crafted to stay unremarkable, to help an intelligence officer dissolve into the ordinary appearance of a public body. The caption for “The Well Dressed Spy” reads, “Intelligence officers … know that quality and craftsmanship have been ‘built in’ to their appearances.”

Low-tech accessories can also help you avoid contact altogether. “Dead Drops” are containers, either too unimpressive or too repulsive to attract a second glance, left at prearranged locations. Two examples are a tubular spike, easily pushed back into the ground, and a taxidermied rat, with a cavity opened up in its abdomen. Similarly, a couple of things with the organic look of corms, rhizomes, or some other kind of underground stem are titled Seismic Intruder Detector Devices, “designed to blend in with the terrain”—layers of relay sedimented deep into nature by the craft of intelligence.

The Pocket History’s last chapter on “9/11 and After” ends with a double-page image showing the scale model of the Abbottabad compound, where Osama Bin Laden was tracked down and killed. This model is an identical double of another kept at the Pentagon, watched in the White House Situation Room while the raid was unfolding. The National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) not only modeled the compound but made a life-sized mock-up of it too, to better train soldiers for the raid. Soldiers interviewed after the operation in May 2011 said that during the raid, they felt like they had been there before.

The craft of intelligence stands out from the natural order of things only retrospectively, either when blown apart by the disastrous force of an ill-fated operation, or when the prescheduled end of a given time frame is met—or when some simulation is revealed as a precursor to a future assault that has already ended. Nature serves as a camouflage for the silent growth of history. History, in return, alters nature in the fashion of retroactive legislations—to be treated as always having had effect. It amounts to the craft of sending public time spinning in a rearward direction, always looping back to the present from a forced revision of the past, again and again, one declassified thing after another, one raid after another.

Mahan Moalemi is a writer and curator based in Tehran. He has a Master of Research degree from the Curatorial/Knowledge program at Goldsmiths, University of London. He is co-editor of Ethnofuturismen (Merve Verlag, 2018) and has contributed to numerous art and literary publications in Iran.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.