Dr. Southern California

Heading west for the cure

Lyra Kilston

Climate is to a country what temperament is to a man—Fate.

—Helen Hunt Jackson, Glimpses of Three Coasts

In the spring of 1602, Basque merchant Sebastián Vizcaíno was sent on a mission to map the California coast for Spain. Several months later, he and his crew docked in a placid bay he named San Diego and some of them went ashore to explore the foreign terrain. There, they encountered an astonishing woman who looked “more than one hundred and fifty years old.”[1]

As Vizcaíno’s journal recounts, the men crossed the sandy beach and were met by a large group of native people armed with bows and arrows. Emerging from the group was the wrinkled, elderly woman, who approached the sailors as an envoy. She was frightened of the pale-skinned, strangely dressed intruders and wept as she walked. The Spaniards, in turn, were shocked by her extremely aged appearance. Her name went unrecorded, but her deeply creased belly was described as looking “like a blacksmith’s bellows.” The sailors offered her beads and something to eat to show their peaceable aims. Tensions broke, and civil relations between the two cultures were established, at least for the day. The story of this impossibly long-lived woman may be one of the earliest sources of one of Southern California’s most enduring myths: the land’s ability to enhance longevity.

Centuries passed without much outside interest in the region beyond that of Spanish colonizers. But in the mid-nineteenth century, a trickle of immigration turned into a flood, transforming the newly recognized state. Gold in Northern California was one lure. Another was the opportunity to explore and document this wild land perceived as “new” and “empty.” Adventurers wrote in rapturous detail of how crops of grapes and citrus would burst from the rich soil, of tranquil weather patterns, and of the varied landscape of mountains, deserts, forests, and ocean. The mysteriously long lifespans of the indigenous inhabitants were also noted repeatedly, adding a supernatural air to the already intriguing land at the edge of the continent.

Doctors, too, fed into the lore. “The climate is so healthy that illness is rarely found and one sees many persons who have reached an age of over a hundred years,” wrote Dr. J. Praslow.[2] Praslow had arrived in San Francisco from Germany in 1849 to practice medicine. He soon set out to make a comprehensive “medico-geographical” (as he termed it) study of the state, becoming one of the first medically trained observers to link California’s geography and climate to its residents’ longevity. During his explorations, Praslow discovered “people here who were from 100 to 115 years old and who were still very active.” He concluded from his records of daily temperature, sun exposure, and agriculture that excellent health could be expected for incoming Pacific Coast settlers.

Around the same time, American physician James Blake reported similar findings about Northern California in The American Journal of the Medical Sciences:

I am but expressing my candid opinion when I state that I believe California will be found more conducive to the highest physical and intellectual development of the Anglo-Saxon race than any other part of the globe. There is not a day in the year in which the powers of the mind or of the body are enervated by heat or numbed by cold. And when the agricultural resources of the country shall become developed, and the swamp lands reclaimed and brought under cultivation, I believe that every external influence, detrimental to the preservation of health, will be reduced to a minimum.[3]

Further south, Italian-born physician Peter Charles Remondino, who cofounded San Diego’s first private hospital in the late 1870s, described the locale in a medical journal as a “paradise of old age.” He believed the region was capable of “setting back, so to speak, the march of our age for a generation or more.”[4] Furthermore, he claimed that the extended lifespan of the native people could be achieved by white settlers, leading them to new heights of physical and mental perfection. The source of this radiant health was proclaimed to be purely geographical, never genetic or cultural. It was the climate, the land, the place, that enabled such long lifespans. One only needed to relocate to reap its benefits.

Connecting health to locale is typically traced back to Hippocrates, who wrote the treatise On Airs, Waters, and Places around 400 BC. It prescribed how best to engage with winds, water sources, seasons, and sun exposure for achieving maximum robustness. The influence of his theory fluctuated over the centuries but gained immense sway in Europe and the United States in the mid- to late 1800s, as rates of illness soared and doctors often proved helpless. By 1860, the notion that health was dependent on place was widely accepted. Eastern American cities, with their humidity, long wet winters, and dense populations, augured inescapable disease. Doctors prescribed journeys to the West or Southwest for climatotherapy, citing the “radically curative and reinvigorating influences” of fresh dry air, ample sunshine, and new scenery.[5]

Before long, newspaper advertisements, books, and travel guides were exalting Southern California’s climate cure. Readers elsewhere in the United States and in Europe were told of constant sunshine and near-instantaneous health recoveries. (One journalist in Pasadena, a town east of Los Angeles, satirized the deluge of boastful miracle-cure testimonies by stating, “When I left home I had but one lung and it almost gone. ... I have been two weeks in Pasadena [and now] have three lungs.”) Southern California was garlanded with romantic monikers and compared to salubrious sites abroad: “The Better Italy,” “The Land of Sunshine,” “The New Palestine,” and “A Mediterranean land without the marshes and malaria,” among others. Aided by the new transcontinental railroad, tens of thousands of people began to head west, permanently transforming the region. It is estimated that between 1840 and 1900, about a quarter of these new arrivals came because of illness; they soon were known as “health seekers.”[6] One historian, noting the newcomers’ belief that locale alone could replace medical care, facetiously suggested a nickname for the area: “Dr. Southern California.”[7] The promises of miraculous recovery were inflated, certainly, and their wide acceptance may appear naive. Yet many desperately ill Americans, having tried every other known cure, pinned their last hopes on this arid, sun-drenched “doctor.”

Medical practice at the time often harmed more than it healed. Bloodletting, purging, and blistering were common, destroying the little strength patients had left. Doses of addictive laudanum and poisonous mercury were liberally prescribed. Doctors still believed the medieval theory that sickness was frequently induced by “miasma”—harmful vapors arising from decomposing matter. (Some believed that a mere breath of miasmatic air, whether it drifted from a sewage-filled city river or radiated from steaming jungles in the tropics, caused the body to begin to decompose and ferment.)

At the same time, urban populations were growing exponentially, while cities’ antiquated systems of plumbing, sewage, and trash collection, not to mention their cemeteries, struggled unsuccessfully to keep pace. The condition of tenements in lower Manhattan was especially dire, as outlined in a New York state legislative committee report from 1857: “The dim, undrained courts oozing with pollution; the dark, narrow stairways, decayed with age, reeking with filth, overrun with vermin; the rotted floors, ceilings begrimed, and often too low to permit you to stand upright.”[8]

The antidote to this drab urban existence, rife with contagion and disease, beckoned. For those who could afford to get there, Southern California offered an alluring remedy. The sky was cloudless, nights cool, days brilliant, nature abundant. No slums or industry yet existed to stain the air. An official state health report of 1870 proclaimed California the “Sanatorium of the World.”

Such makeshift regimens, reliant on climatic cures, were also practiced in the warmer parts of Europe. But a more formalized health infrastructure was being developed in Europe’s colder climes, blending the efficiency of a hospital with the comforts of a hotel. A rural setting was paramount, reflecting the rising medico-geographical belief in nature cures, as well as the naturopathic method of holistic, drugless treatment.

In the middle of the nineteenth century, a hydropathic physician named Countess Marie von Colomb arrived in Görbersdorf, a village tucked into a pristine valley near what is now the Polish-Czech border. Colomb had studied with the famous self-taught Silesian peasant Vincenz Priessnitz, the “father of hydrotherapy,” and was seeking a location to open a clinic of her own.[9] Görbersdorf, surrounded by the lushly forested slopes of the Stone Mountains, offered clean air and fresh water, and like Priessnitz’s popular clinic, was at high altitude.

Colomb’s water-cure clinic prescribed a regimen of wet compresses, drinking copious amounts of spring water, several cold showers and baths daily, vigorous hikes, and sleeping with windows open in all seasons. Pleased with the clinic’s progress and its tranquil setting, she invited her brother-in-law, Dr. Hermann Brehmer, to visit. A botanist turned physician, Brehmer was also in search of a healthful locale to begin receiving patients. His medical research on the treatment of tuberculosis was centered on the theory of an “immune place.” After touring the valley and seeing Colomb’s clinic, he agreed that the location might offer the elusive immunity he sought.

Launching his practice in Görbersdorf in 1854, Brehmer began to treat a small number of consumptive invalids. His system included water treatments and hiking (or “methodical hill-climbing” as he called it), as well as a diet of milk, fatty foods, vegetables, and a nightcap of cognac. In time, he was able to acquire a large piece of land and undertake the construction of an imposing, thick-walled sanatorium. As word spread of this new type of tuberculosis treatment, and its magnificent facility and location, Brehmer’s Heilanstalt für Lungenkranke (literally, “healing institution for the lungsick”) grew, eventually housing several hundred patients.

Fusing the grandeur of towering Gothic architecture with elements of a homey Alpine chalet, Brehmer’s sanatorium offered everything required for an extended stay. In addition to a medical laboratory, amenities included a meteorological observatory; a vast library; men’s and women’s parlors; communal dining rooms; private bedrooms (whose windows were to remain open all night); and its own dairy, kept under strict hygienic supervision. No carpeting was permitted (a fibrous den of germs!), and air shafts and ventilators kept fresh air cycling through the building.[10] The sanatorium was surrounded by a vast forest laced with walking paths that offered the outdoor exercise Brehmer “prescribed,” the intensity of which he calibrated to his patients’ gradually improving strength. Brehmer believed that regular physical activity in the high-altitude air would strengthen the hearts of tubercular patients, which in turn would heal their lungs. This was not strictly true, but nonetheless his regimen did improve the health of many patients who arrived in the early stages of the illness.

Brehmer’s methods, and his synthesis of medical science with the healing properties of a salubrious locale, sparked a sanatorium movement that spread across Europe. (The term sanatorium is from the Latin sanare, to heal.[11]) It proliferated first in mountainous regions, where the sunlight was stronger and the air so clean it was said to taste like champagne. High-altitude villages like Görbersdorf and Davos, Switzerland, became famous health resorts, attracting invalids (who could afford the fees) from across the continent.

Davos’s renown began with Dr. Alexander Spengler, a German physician assigned to serve the small, mile-high farming village. Astride his horse, with his medical bag in tow, Spengler visited patients in the snowbound valley and began to notice an intriguing lack of tuberculosis. Instead, it was common, he observed, for locals to possess “a beautiful, symmetrical body, a bulging chest and a strong heart muscle,” as well as impressive stamina for scaling steep mountain slopes without becoming breathless.[12] Was it possible that, like Görbersdorf, this was an immune place?

Spengler could soon put his hypothesis to the test. In the middle of the bleak winter of 1865, he received two frail German invalids who had heard rumors of the illness-free valley. Exhausted from the nine-hour sleigh ride to reach Davos, they were taken under Spengler’s care. They followed the doctor’s instructions—most importantly, exposing themselves daily to the pure, bracing mountain air—and recovered after one season. Their triumphant story spread far and wide. Meanwhile, Spengler broadcast his victory to the medical community, and set about building a kurhaus (“curehouse”). It possessed long, wide porches for outdoor rest, where patients lay on chaise lounges for hours imbibing sunlight and brisk air. His healing regimen was unique. He prescribed “stabulation,” or sleeping in cow sheds to inhale the pungent vapors of the animals’ urine, taking cold showers even when the spray would turn to ice, and being massaged with marmot fat—a rich and easily absorbed liniment rendered from the alpine rodent and believed to be curative.

Eventually, good rail connections enabled Davos to develop into one of Europe’s most popular locations for health seekers. At first, they came only in summer, but belief in the antiseptic benefits of the unsullied, frosty air soon brought them in droves in winter as well, when they would wade through thigh-deep snow and sleep with windows flung wide open. More sanatoriums opened to receive the ever-increasing flood of patients. Their architecture evoked the lavish hotel-like model of Brehmer’s in Görbersdorf, but enhanced the patients’ exposure to sunlight and mountain air through south-facing windows, porches, and balconies. Frequently, the rooms featured hygienic interiors, with linoleum flooring and disinfectable furniture. Dietary regimens varied, but each institution monitored its patients’ meals closely, and prescribed schedules of rest, promenades, hydrotherapy, and ceaseless exposure to fresh air. To mitigate the isolation and the constant shadow of death, familiar domestic distractions were offered. One account of an alpine sanatorium described patients “clothed in long flannel dresses, … up to their necks in water in a common bath, where they remain for several hours together. Each bather has a small floating table before him, from which his book, newspaper or coffee is enjoyed.”[13]

Soon, “taking the cure” at a sanatorium was entrenched in European culture, claiming its own customs, tools, and rituals. It became as normal as leaving behind one’s home and family for an unknown period could be.

Trudeau read extensively about European sanatoriums and sought to institute a similar practice in the United States. The tranquil location on the shore of Saranac Lake, where he had lain for many days under the tall trees gazing out at the water, presented itself as ideal for treating patients. “I then unfolded ... my plan of building a few cottages at Saranac Lake ... where I could test Brehmer’s and Dettweiler’s rest, open-air, and sanatorium methods.”[15]

The doctor purchased ninety acres on the lake with the help of investors and the buildings for his institution began to rise, with facilities for administration, research, and caregiver training, as well as a laboratory with the latest medical equipment. Wanting to avoid a massive building with dark hallways and small windows, like Brehmer’s gothic building in Görbersdorf, Trudeau preferred the homier style of “cure cottages.” These houses varied in style and size—from a gingerbread Queen Anne look to Swiss chalet to English countryside—but all featured, crucially, effective air circulation and space for outdoor repose. During the long, icy winter, patients reclined outdoors, swaddled in blankets and fur.

The patients’ regimen was strict: alcohol, smoking, cursing, and intimate relations were forbidden. (The phrase “cousining” referred to illicit romantic affairs among patients; according to one source, a secluded gazebo on the grounds was called the “cousinola.”) The doldrums of open-air reclining were also alleviated with mandatory arts and crafts classes, formal dinners, and an enforced culture of optimism.

Trudeau’s sanatorium gained in reputation, even though the success of his methods was relatively limited in that he only accepted patients in the very earliest stages of the disease, some of whom would have improved regardless. Many curious doctors and health officials visited his Adirondack Cottage Sanatorium and soon Trudeau’s methods were replicated across the country. Word was also spread by celebrity patients. The author Robert Louis Stevenson, for example, found his health greatly improved at Saranac Lake and often recommended this “American Davos.”

However, not every “lunger” (as some tuberculars called themselves) could afford to travel to sanatoriums and pay the fees for room, board, and medical treatment. A network of free sanatoriums paid for by charitable, religious, or state institutions emerged, but beds filled quickly. Instead, the majority of the afflicted were cared for at home by relatives, despite the looming threat of contagion. Or, if they could afford the train ticket and survive the journey, they might relocate to the natural sanatorium of Southern California.

One of the early boarding houses for consumptives was founded in 1882 by Emma C. Bangs, who arrived from the east with her ill daughter. Having purchased land overlooking a deep, dry gulch in Pasadena, Bangs had a two-story wooden house built and began taking in tenants, many of whom came for the winter. One resident, Mrs. Jennie Banbury Ford, recalled this remarkable anecdote:

When Mrs. Bangs’ boarding house was most flourishing, there were many consumptives coming and going. It became so depressing it was suggested that they band themselves together under the head of “the busted lung brigade,” and create more hopeful and cheerful feeling. The suggestion was carried out and proved very successful. They elected officers, had a beautiful silk banner with “B. L. B.” embroidered on it and met all “busted lungers” with open arms. Those whose stay was ended were started on their several ways with smiles and cheers. Each member was compelled to sign the by-laws, which were amusing at least. They must “not sit in a draft, must consume just so much milk and so many eggs each day and look after each other’s comfort, etc.” To help the fun along, Mrs. Bangs bought a parrot in Los Angeles who knew how to cough exactly like a “lunger” and contributed much to the amusement. I don’t believe a more grotesque club ever existed, do you? It lasted for several years.[17]

The cheerfulness of the “busted lung brigade” aside, most health seekers had a less jubilant time. The high population of invalids had attracted a flood of doctors, or those posing as such, whose methods of healing were often eccentric and unregulated. Attempts to establish a state medical board faced fierce and constant resistance. In the first of its several iterations, in the late 1870s, it issued three separate licenses: for conventional medicine, eclectic medicine, and homeopathic medicine.[18] Unfortunately, it was impossible to pursue and fine the scores of unlicensed practitioners, some of whom vocally objected to the very notion of being tested and licensed in the first place. “In a country where sickness was once almost unknown,” observed British novelist Horace A. Vachell, “doctors, dentists, faith-healers, and quacks multiply and increase as the quails of yore.”[19] If an invalid was not under medical supervision, by choice or economic necessity, it was often up to them and their caretaker to perambulate from inland heat to coastal mist, mountain pines to valley shade, experimenting with atmospheres like ingredients to be measured and decanted into an airy elixir.

As the century drew to a close, the perception of tuberculosis changed. News of the disease’s easily communicable nature was dispersed widely through public health campaigns, amplifying concerns over the danger it posed. An ordinance against spitting in public spaces was passed in Los Angeles in 1896 to stave off contagion. As historian Emily K. Abel points out, by “spreading the message that contact with a tubercular could be deadly, health educators transformed sufferers into menaces.”[20] Panic spread faster than the deadly bacilli.

After years of advertising the region quite explicitly to lure invalids, residents now complained that promoting health services would only burden the area’s resources. Tales circulated of penniless consumptives with multiple children in tow arriving by train and collapsing at the station. In the Los Angeles area, charitable institutions and the free county hospital were over capacity and understaffed. Eventually, locals passed a law decreeing that only county residents of at least one year could get free medical treatment, trying to ward off the steady flow of ill and impoverished newcomers. Suspicion and hostility were especially heaped upon non-white Californians, such as laborers of Native American, Chinese, and Mexican heritage, who were viewed as likely carriers of the disease. “We wish more population of the right sort,” read a coded 1895 editorial in a promotional magazine called The Land of Sunshine. “But we are particular. We are anxious to have our friends come; but not everybody.”[21]

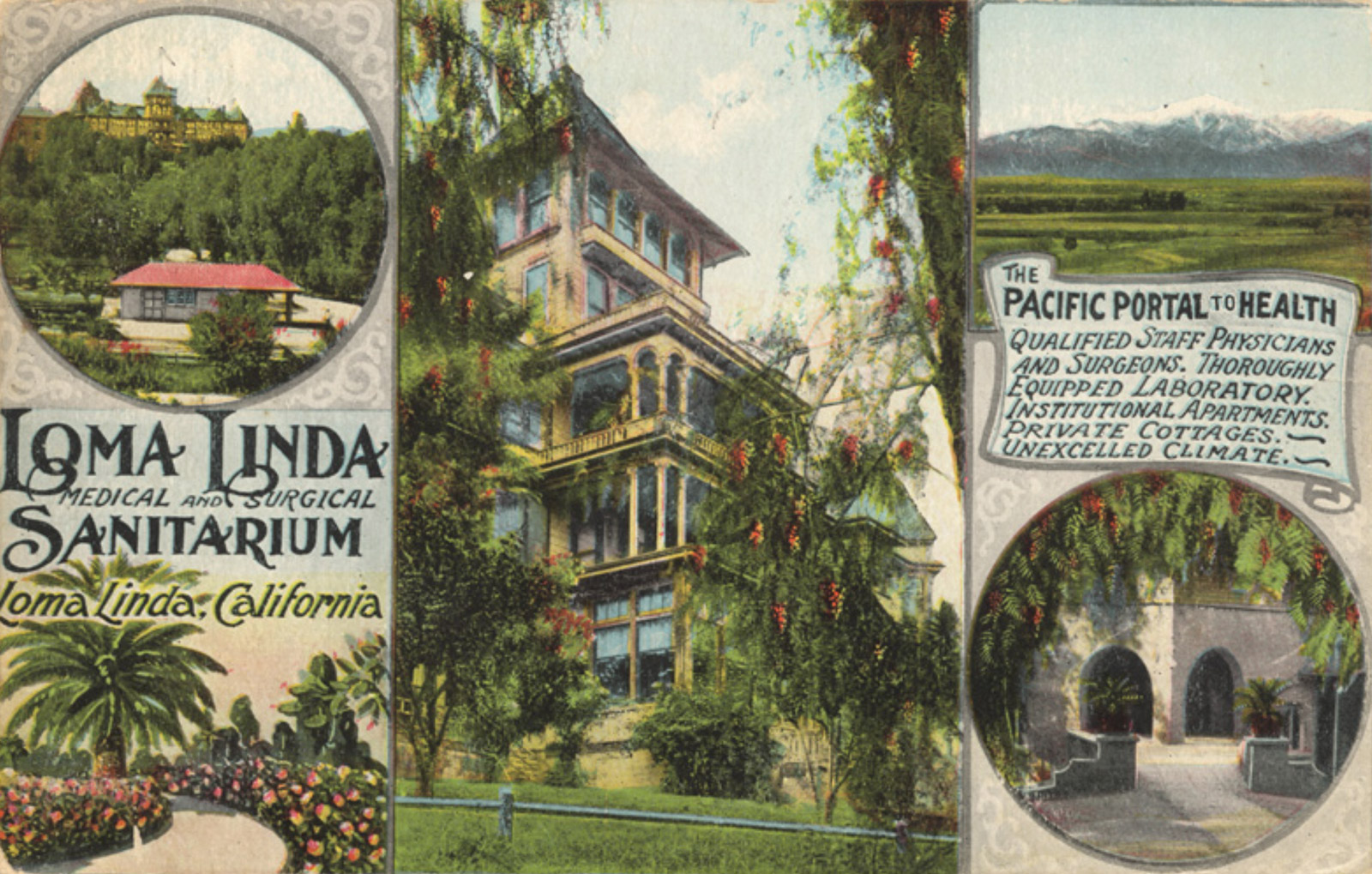

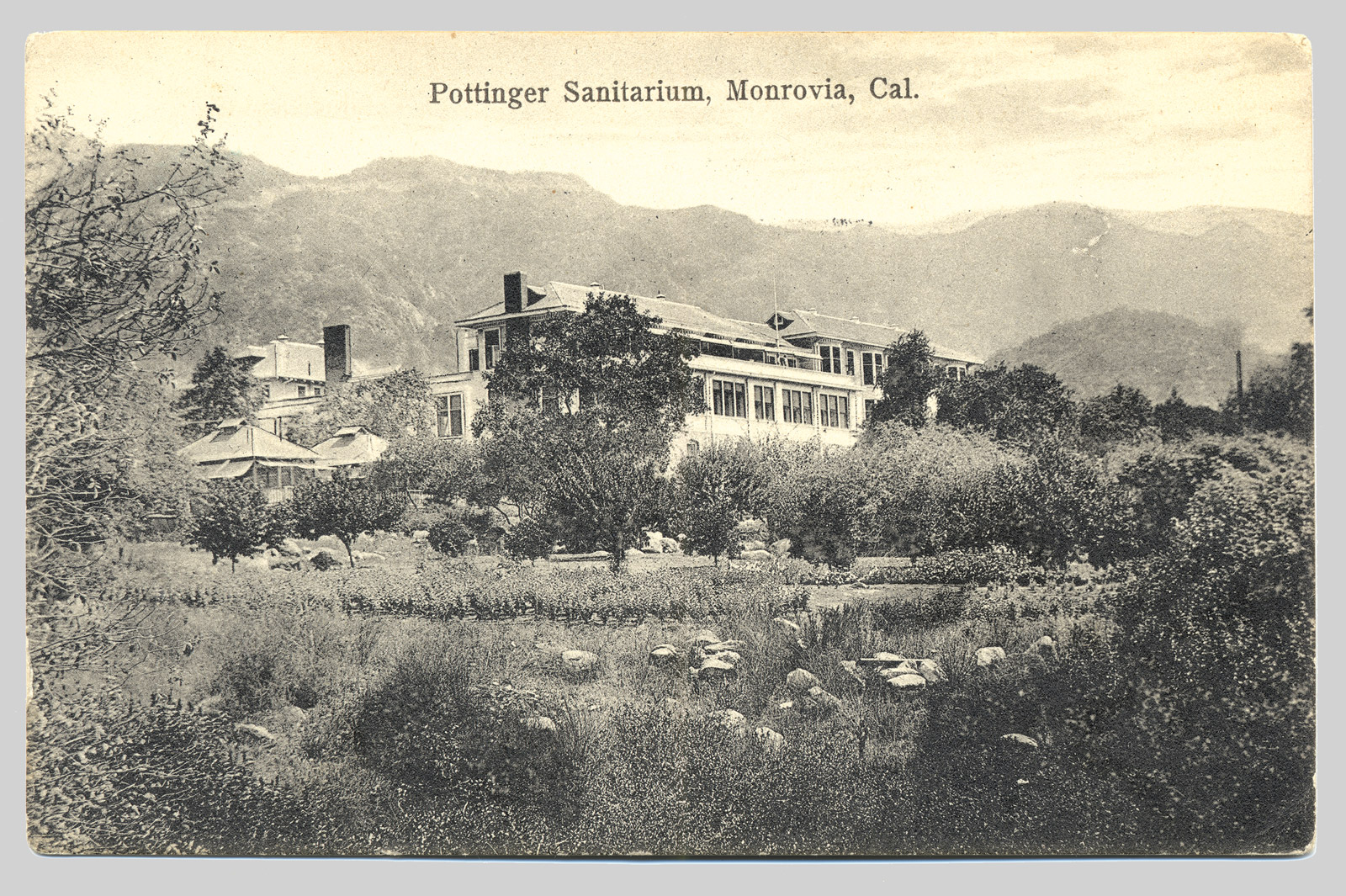

In order to contain the disease, consumptives were encouraged to enter sanatoriums skirting the city, staffed with doctors and nurses enforcing their unique diets and strict daily schedules. The Barlow Sanatorium, funded by charitable donations, opened in 1902 for indigent consumptives. They were housed in secluded hillside bungalows, forbidden to spit, and started each day with a plunge into cold water. A year later the Pottenger Sanatorium, set amid fragrant citrus groves on a south-facing mountain slope, opened with eleven beds. Its founder, Dr. Francis M. Pottenger, had traveled to Southern California with his wife in an attempt to cure her consumption. As her health failed, Pottenger devoted himself to researching the disease and its possible cures. Influenced by reading about the success of Brehmer’s and Trudeau’s methods and by his personal observation of their institutions in Görbersdorf and Saranac Lake, he decided to build his own sanatorium, suited to the unique, health-giving climate of his new home.

“My task,” recalled Pottenger, “was to adapt the buildings to the year-round open-air life in Southern California.”[22] To this end, he housed patients in canvas tents three sides of which were made of wire netting and open to the air. The resulting exposure to sunlight and air, as well as a diet of garden-grown vegetables, fresh dairy, and copious doses of the “Pottenger cocktail” (orange juice, soda, and castor oil) proved beneficial. His institution, which eventually supported up to a hundred patients, gained widespread prestige due to its modern methods and strong recovery rate. Other institutions followed; by 1911, there were at least twenty-three facilities for the treatment of tuberculosis across California and a few years later, those that accepted lower-income patients began receiving state funds.[23]

And yet, the lore of California’s miracle climate was being steadily eclipsed by a drive to redefine the region’s identity. Working in tandem with a slew of laws tracking or excluding consumptives, promotional publications shifted gears. Now they hawked the miracles of plentiful business opportunities and cheap land, hoping to lure hearty, industrious families instead of the weak and dying. California was recast as a place where the healthy could get even healthier. If an orange grew into a remarkably vibrant globe in the dead of winter, if the oldest and largest trees in the nation soared out of California soil, what then might happen to a strong and healthy person?

No longer were desperate invalids free to investigate curative microclimates or fill brocaded hotel hallways with the pathos of their coughs. The years of unregulated health seeking were drawing to a close, but the region’s reputation had been sealed.

This essay is a modified excerpt from Lyra Kilston’s recent book Sun Seekers: The Cure of California (Atelier Éditions, 2019).

- Sebastián Vizcaíno, “Diary of Sebastián Vizcaino, 1602–1603,” in Spanish Exploration in the Southwest, 1542–1706, ed. Herbert Eugene Bolton (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1916), p. 81.

- J. Praslow, The State of California: A Medico-Geographical Account, trans. Frederick C. Cordes (San Francisco, John J. Newbegin, 1939). The book was originally published in Göttingen, Germany, in 1857.

- James Blake, “On the Climate and Diseases of California,” The Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal, vol. 78, no. 193 (October 1852), p. 303. Blake’s article was first published in The American Journal of the Medical Sciences, no. 47 (July 1852).

- Peter Remondino quoted in Kenneth Thompson, “The Idea of Longevity in Early California,” Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, vol. 51, no. 7 (July–August 1975), p. 813.

- Physician Daniel Drake quoted in Kenneth Thompson, “Climatotherapy in California,” California Historical Quarterly, vol. 50, no. 2 (June 1971), p. 117.

- These figures are drawn from Sheila M. Rothman, Living in the Shadow of Death: Tuberculosis and the Social Experience of Illness in American History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), p. 132.

- John E. Baur, The Health Seekers of Southern California, 1870–1900 (San Marino, CA: Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery, 2010), p. 12.

- Report of the Select Committee Appointed to Examine into the Condition of Tenant Houses in New-York and Brooklyn (Albany, NY: C. Van Benthuysen, Printer to the Legislature, 1857), p. 14. This section of the report is quoting an undated newspaper article “from the pen of Mr. Spaulding, of the N.Y. ‘Courier and Enquirer.’”

- Priessnitz advocated for cold water treatments, breaking from the established European spa traditions of seaside cures and visits to pungent mineral springs. His methods invoked skepticism among many (local authorities often raided his clinic to examine his sponges for sorcery or hidden drugs), but were widely replicated and absorbed into other health regimens.

- Frederick Rufenacht Walters, Sanatoria for Consumptives: A Critical and Detailed Description Together with an Exposition of the Open-Air or Hygienic Treatment of Phthisis (London: Swann Sonnenschein, 1902), pp. 151–153.

- Sanatorium, sanitarium, or sanitorium? The difference lies between the Latin roots sanitas (health, sanity) and sanare (to heal, to cure). The form varied by country, and sometimes even by doctor. With such similar words in use, the results were often muddled. Here, sanatorium is used to mean a nature-cure institution.

- Alexander Spengler quoted in “O Switzerland!”: Travelers’ Accounts, 57 BCE to the Present, ed. Ashley Curtis (Basel: Bergli Books, 2018), p. 11.

- Quote from a Baedeker guidebook in Andrew Beattie, The Alps: A Cultural History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 184.

- Edward Livingston Trudeau, An Autobiography (Garden City, NY: Doubleday Page and Company, 1916), pp. 10–11.

- Peter Dettweiler was a physician who was one of Brehmer’s former patients at Görbersdorf. He stayed on after his recovery and worked with Brehmer for a number of years as one of his assistants, before leaving in 1876 to found the Falkenstein sanatorium in Germany’s Taunus mountains. Where Brehmer emphasized vigorous blood-pumping exercises for invalids, Dettweiler pioneered the rest cure—an approach that would prove more enduring. His sanatorium provided deep verandas and cane recliners for patients to lie on while benefiting from the mountain air. He also founded Germany’s first “people’s sanatorium” for invalids of low income—a model that would proliferate throughout the nation and beyond.

- Los Angeles’s population was estimated to have increased from 11,000 to 80,000 in the 1880s. See Glenn Dumke, “The Boom of the 1880s in Southern California,” Southern California Quarterly, vol. 76, no. 1 (Spring 1994), p. 105.

- J. W. Wood, Pasadena, California, Historical and Personal (n.p.: published by the author, 1917), pp. 120–121.

- See Linda A. McCready and Billie Harris, From Quackery to Quality Assurance: The First Twelve Decades of the Medical Board of California (Sacramento: Medical Board of California, 1995). “Eclectic medicine,” a term in use from about 1830 to 1930, referred to a theory of botanical treatments and physical therapy, but was also used to encompass any approach that was not conventional.

- Horace A. Vachell quoted in Carey McWilliams, Southern California: An Island on the Land, (Layton, UT: Gibbs Smith, 1973), p. 100.

- Emily K. Abel, Tuberculosis and the Politics of Exclusion: A History of Public Health and Migration to Los Angeles (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2007), p. 21.

- Emily K. Abel, Suffering in the Land of Sunshine: A Los Angeles Illness Narrative (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2006), p. 53.

- Francis M. Pottenger, The Fight Against Tuberculosis: An Autobiography (New York: Henry Schuman, 1952), p. 125.

- See Philip P. Jacobs, A Tuberculosis Directory Containing a List of Institutions, Associations and Other Agencies Dealing with Tuberculosis in the United States and Canada (New York: The National Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis, 1911), pp. 13–16. For further reading on the number and type of health facilities in the Los Angeles area in the first decades of the twentieth century, see Emily K. Abel, Tuberculosis and the Politics of Exclusion, pp. 39–51.

Lyra Kilston is a writer and editor based in Los Angeles. Her first book, Sun Seekers: The Cure of California (Atelier Éditions, 2019), examines three moments in Southern California history and the many eccentric newcomers—from fervent nature-cure healers to modern architects to barefoot vegetarian hermits—who built up the region’s renown as a center for healthy, natural lifestyles around the turn of the twentieth century. Her next project is on 1970s ecological architecture in the American West.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.