Academic Discipline

A history of prisons and privilege at German universities

Reed McConnell

Wilhelm Rumpf is a naughty boy, and Schoolmaster Heinzerling isn’t having it. When Dr. Heinzerling walks into his classroom one morning to find Rumpf holding forth in an uncanny imitation of his own peculiar manner of address, he sentences him to three days in the school jail, or Karzer.[1] “At the naext stopaid traick I’ll aexpel you!” he tells Rumpf a few hours later while visiting him in his cell. “Pot yourself ain mai place.”[2] Rumpf, convinced that his expulsion is inevitable, takes this last injunction literally, locking Heinzerling in the Karzer and giving orders in Heinzerling’s voice until he decides to strike a deal. Clear my name, he tells Heinzerling, and I’ll never tell anyone that I outwitted you. [3] The deal holds, and no one is the wiser.[4]

First published in 1872, Ernst Eckstein’s short story “Der Besuch im Carcer” is a classic text in German high school classes and thematizes what was once an equally classic element of German universities and secondary schools. Starting in the sixteenth century, many educational institutions had their own jails, ranging in size from single rooms at boarding schools to entire wings or small buildings at larger universities. Students would be sent there for everything from general cheekiness to actual lawbreaking. As corporations, German universities had full jurisdiction over their students, meaning that they could send them to the Karzer for the sort of illegal conduct that would have landed townspeople in local jails.[5] But Karzer sentences were also meant to have an “educational function,” with sentences often arising from simple violations of the university code or behavior otherwise deemed improper.[6] These violations ranged from the banal to the bizarre.

The Leipzig University archive contains a record of all of the Karzer punishments meted out to students at the university between 1862 and 1879. The offenses range widely. Georg Adolph Waldemar Fischer, for example, was given fourteen days in the Karzer “for breaking his word of honor twice; for drunkenness [and] a disorderly, slovenly, and vagabond-like lifestyle,” and then expelled. Friedrich August Emil Thomas was given three days in the Karzer for purposefully smashing a street lamp; Franz Heinrich Adolph Matthes twenty-four hours for ripping down a poster; Ernst August Ludwig Wilhelm Martini three days for “excess in the streets.” The list goes on. The young men were punished for having girls in their rooms, defaming and attacking night watchmen (one of the most common offenses), participating or aiding in duels, and “roaming around at night.” Others were more lucky: Falk Wilhelm August Berold von Tettenborn, accused of “devilment,” and Carl Heinrich Hermann Herklotz, who was placed under investigation for “heavy drunkenness” after having an epileptic seizure, seem to have narrowly escaped the Karzer.[7]

Karzer were found throughout Germany, and the crimes for which students were sent to them remained relatively consistent. Students could end up in the Würzburg Karzer for playing dice, visiting two bars in the same night, bathing in the Main River, bringing a weapon to a lecture, or blasphemy.[8] But the two most common crimes across the board were participating in duels and causing nighttime disturbances: even an eighteen-year-old Karl Marx was given a night in the Bonn Karzer—from 16 to 17 June 1836—for making a “nocturnal racket.”[9] While less ubiquitous than in the German states, the practice was also found elsewhere in Europe. The University of Tartu in Estonia sent students to the university jail, or kartser, for everything from failing to pay library fines and “hiding one’s name and social class” to—in one particular case—gouging another student’s eyes out with a walking stick during a fight in a brothel. (This last offense generated a sentence of four months, several times the length of the average sizable sentence.)[10] And the University of Coimbra, Portugal’s premier university, founded its academic prison in 1541 in the ruins of the dungeons built in the fourteenth century for the Royal Palace.[11] It was in use until 1834 and today is the only surviving medieval prison in Portugal.

Prisons were not a common means of punishment in and of themselves in medieval and Renaissance Europe. Instead, they functioned far more like modern jails, serving as mere holding pens for those who had been convicted of crimes until their punishments were determined. After sentencing, lawbreakers were charged fines, thrown in the stocks, banished, tortured, or killed. And with the expansion of colonialism in the 1600s, those who ran afoul of local authorities were often simply sent away to live in prison colonies. It was not until the eighteenth century that imprisonment became a common form of punishment in Europe.[12]

However, the earliest Karzer appeared before this shift. One of the oldest and most famous of these was the Heidelberg Karzer, which was built in 1545.[13] Its first iteration was essentially a badly kept dungeon; one inmate said that “due to the awful mists, no one can stay in there long without dangerous illnesses.”[14] In April 1594, a young man named Caspar Flaminius was thrown into the Karzer due to a serial inability—or refusal—to pay his debts. Apparently, whenever he was able to convince creditors to push back a date of repayment, he would rush to someone else and borrow more money, and his final, lengthy list of creditors included a professor, multiple local merchants and cobblers, and the innkeeper of a local guest house called Zum Schwert. The creditors petitioned the university for his arrest, and he spent over two and a half years in the Karzer, his feet chained to prevent possible escape and his clothing rotting on his body from the dampness of the air. He was ultimately released not out of mercy, but because his father finally arranged for his loans to be repaid.

The Heidelberg Karzer remained small and dank until the mid-1730s, when an entirely new two-story structure was erected adjacent to the university’s central building. It featured two cells, as well as living quarters for the caretaker on the ground floor.[15] However, the two cells were not quite sufficient: the number of arrests was high enough that the caretaker was occasionally forced to imprison student convicts in his own home. Between 1822 and 1823, the top floor was significantly expanded to add four more cells, as well as a room for an attendant.[16]

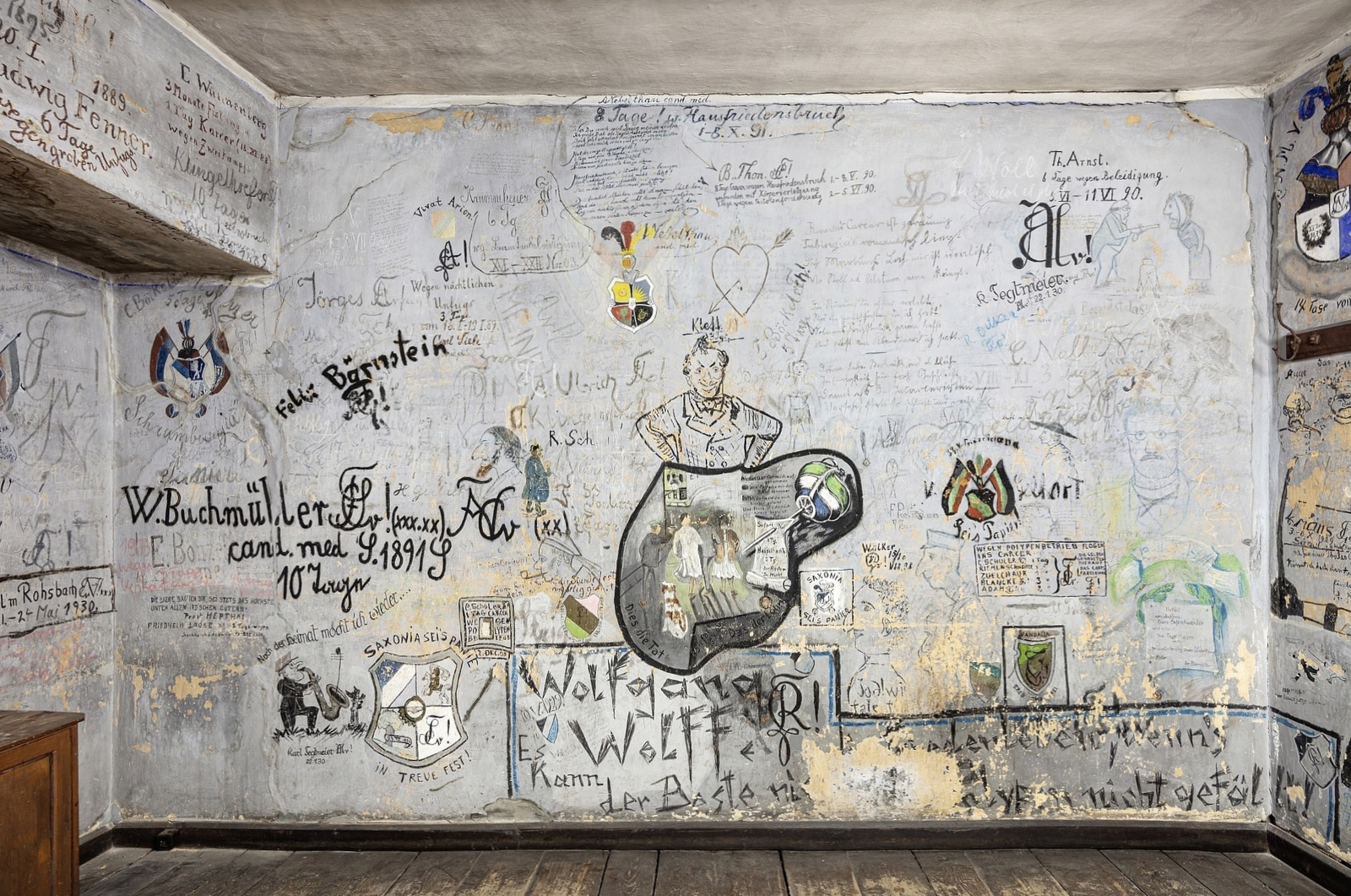

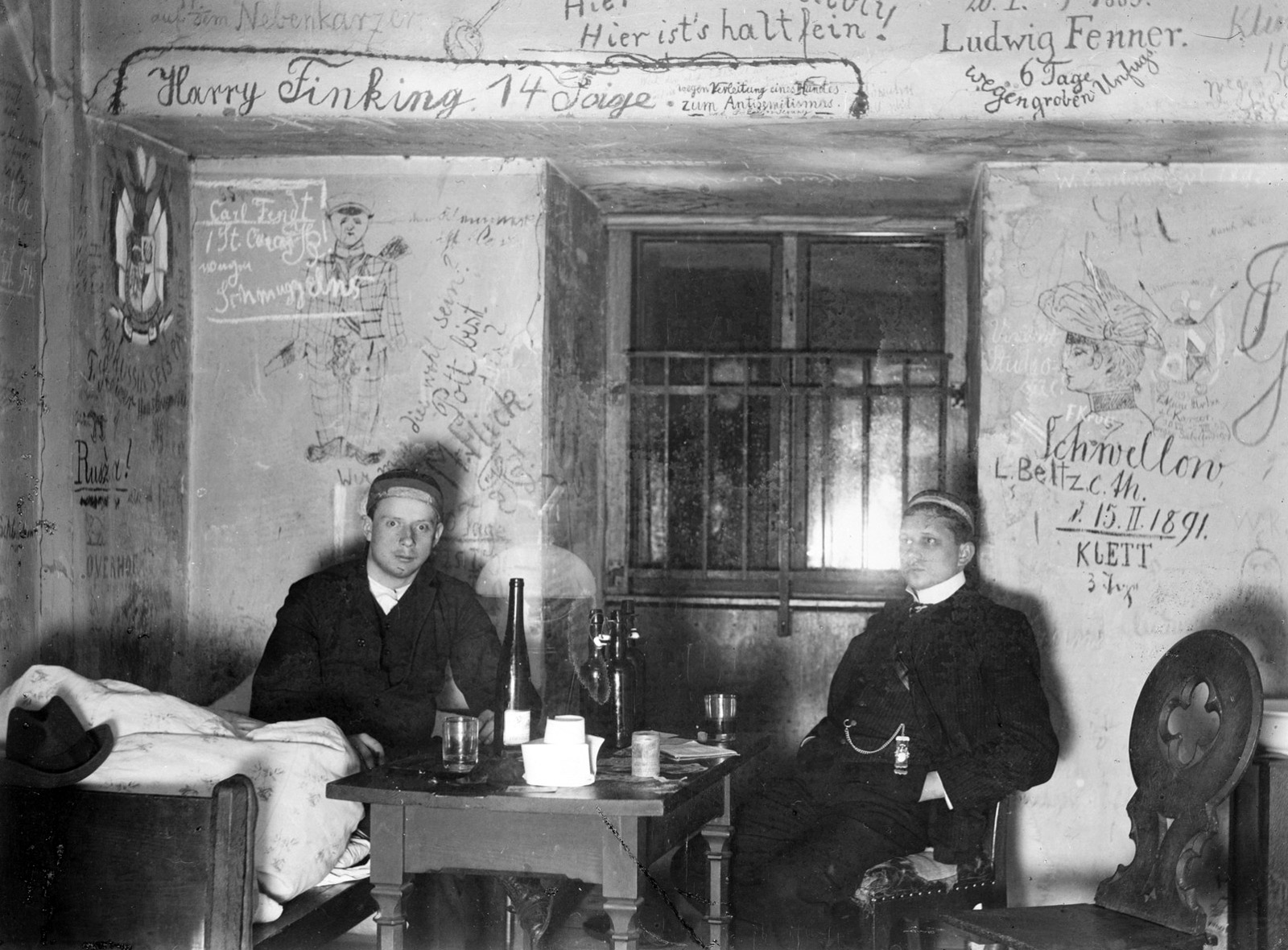

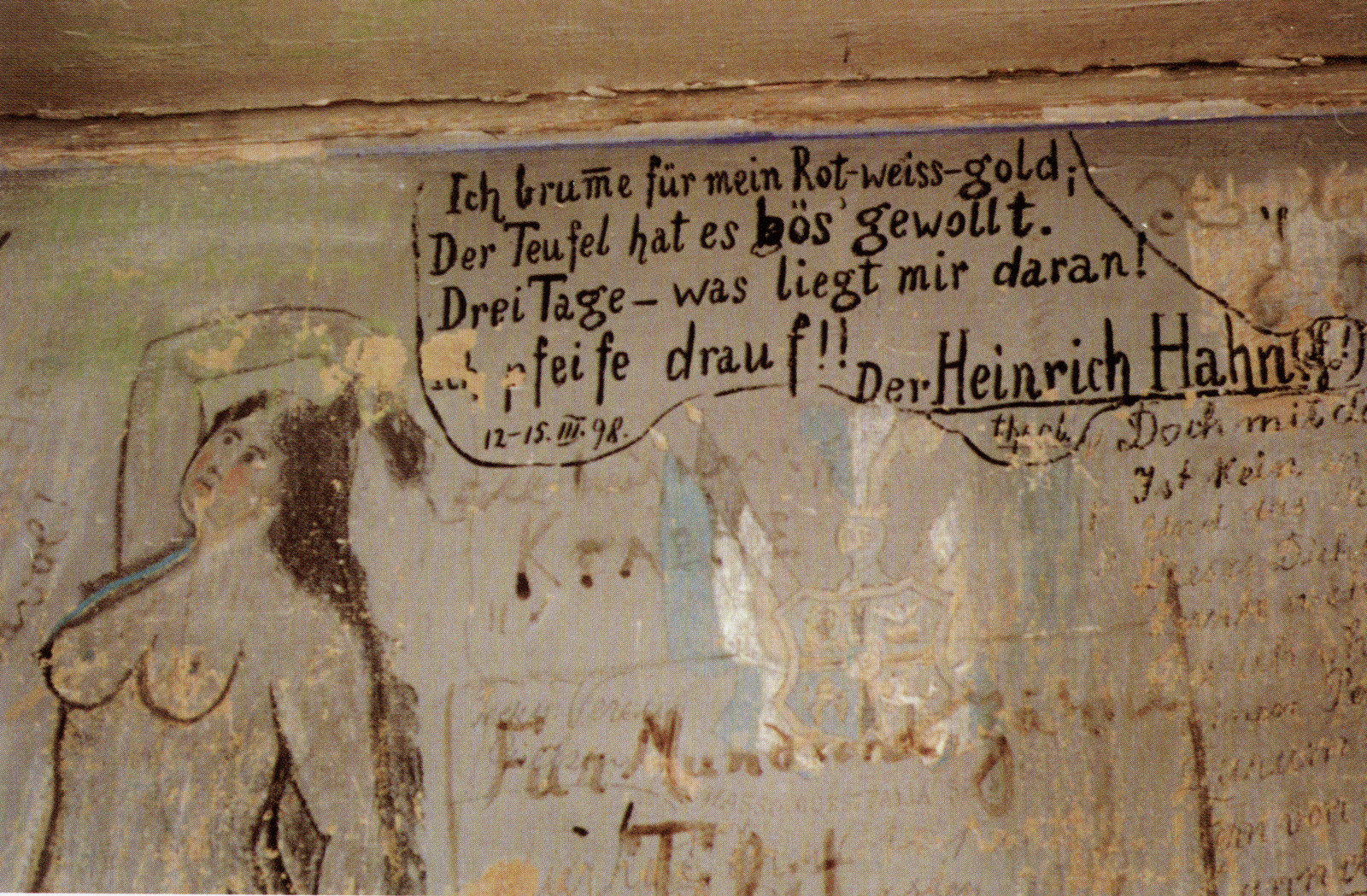

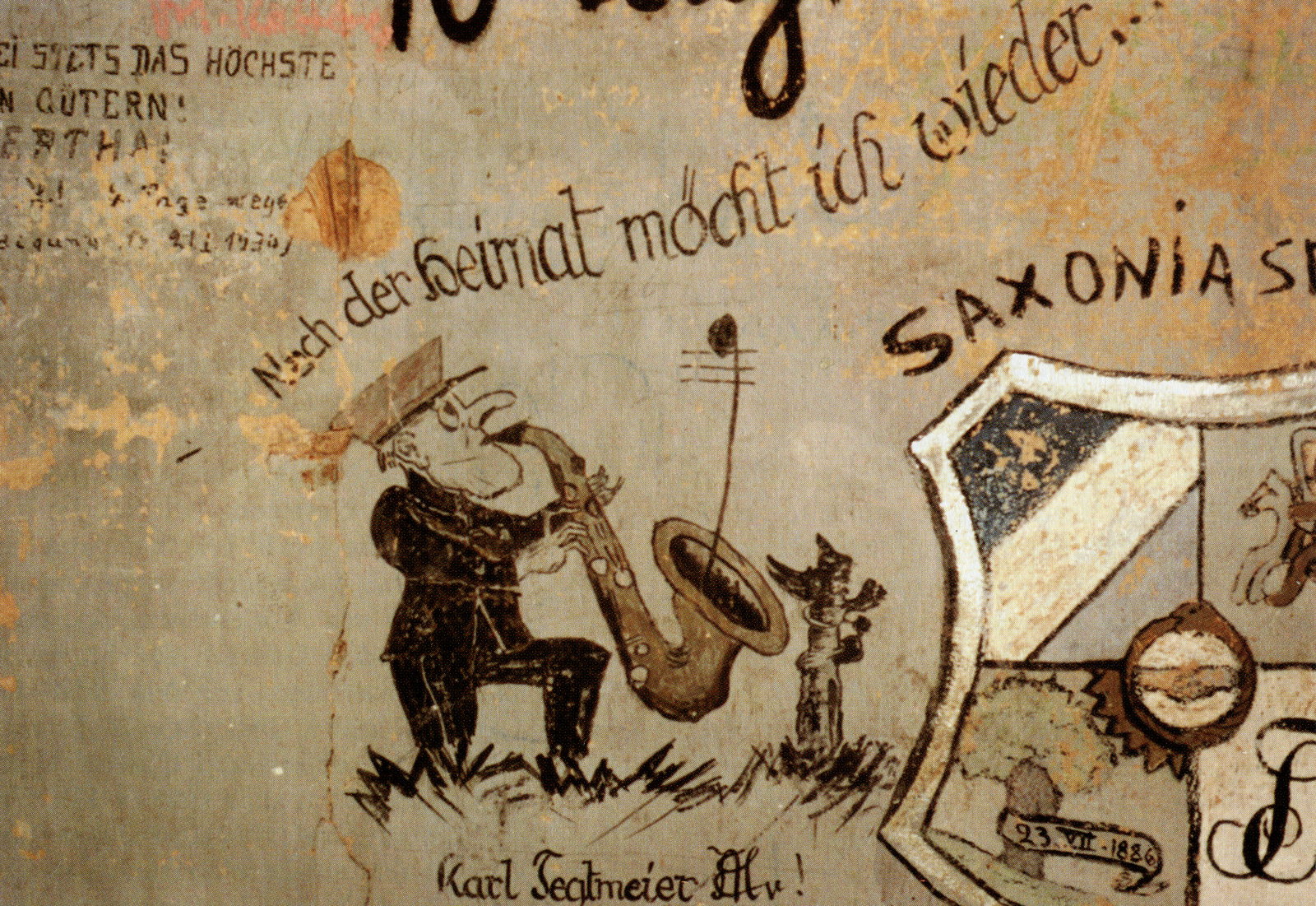

Today, the Heidelberg Karzer is best known for the murals and writing on its walls. Until it was taken out of commission in 1914, prisoners filled its rooms with graffiti, painting depictions of their crimes and documenting their complaints about the amenities. “Abandon all hope, ye who enter here!” reads an inscription, misspelled in Italian, above the first landing of the staircase leading into the Karzer.[17] Once inside, one sees names for each of the four main cells painted on the walls: Sans-Souci, Palais Royal, Solitude, and Villa Trall.[18] (In The Student-Life of Germany, an 1841 book of travel essays, British writer William Howitt recounts an earlier set of names for the rooms, including “the Hole,” which he describes as “the dark place into which the nightly disturbers are thrust, that they may here, undisturbed and undisturbing, exercise their fancies till morning.”)[19] Inscriptions like this, as well as lamentations for absent sweethearts, lyrics to drinking songs, and documentation of crimes and sentences, were commonplace in German Karzer. In 1895, a student named Harry Finking scrawled a text entitled Zur Naturgeschichte des Carcers (Toward a natural history of the Carcer) along a doorframe in the Marburg Karzer:

The Carcer (captivitas academica) is a rare plant that thrives in Central Europe in areas of high culture. It blooms for one to several days, seldom longer than two weeks. Its care demands generous watering with beer or other substances regulated by fraternities, for which reason it is considered to be a luxury plant. Some elder scholars ascribe it healing effects, yet this superstition has been disproven through the thorough investigations of younger researchers. However, the plant is highly valued by connoisseurs as an indulgence.[20]

Numerous, too, are the images, which vary dramatically in skill level and content. They depict students out on the town, caricatures of professors, naked women, and a variety of animals. One recurring motif is negative depictions of police officers, who in the nineteenth century were pejoratively referred to as Polypen, an antiquated German word meaning “octopuses,” because they were thought to reach out and grab their victims like an octopus catching hold of its prey with its tentacles. A drawing from the Marburg Karzer features an officer with an enormous belly and tiny legs; another features an angry rhinoceros in a constable hat labeled “Polyp.”

Such graffiti has fascinated generations of visitors to Germany. In his travel account A Tramp Abroad, Mark Twain recounts being told about the university Karzer during an 1878 visit to Heidelberg. Delighted by the concept, he managed to secure a visit and recorded some of the inscriptions he saw on the walls: “In my tenth semestre (my best one), I am cast here through the complaints of others. Let those who follow me take warning”; “Three days without cause, apparently out of curiosity”; and “E. Glinicke, four days for being too eager a spectator of a row.”[21]

Charmed, Twain attempted to buy one of the tables that had been sitting in the Karzer for decades, if not centuries, bearing the markings and graffiti of generations of students. Alas, the table was not for sale, unless Twain wanted to wait for the attendant to get approval from his superior, who would then need approval from his superior, who would then need approval from his superior. It was turtles all the way up.[22]

The plenitude and content of the graffiti that so delighted Twain reflects a shift in the nature of imprisonments in the Karzer. In 1877, a nationwide change in the law shifted jurisdiction over criminal conduct from universities to local governments.[23] Accordingly, universities were stripped of their power to punish students for anything beyond mere infractions of the university code. This sped up a trend that had been underway for decades: Karzer were losing their power to inspire fear and, toward the end of the nineteenth century, began to close one by one. By the late 1800s, spending a night in the Karzer was treated almost uniformly as a lark and a rite of passage rather than an actual punishment. Twain sketches an exchange of the sort that he imagines might happen between a student and a constable sent to bring them to the Karzer:

“If you please, I am here to conduct you to prison.”

“Ah,” says the student, “I was not expecting it. What have I been doing?”

“Two weeks ago the public peace had the honour to be disturbed by you.”

“It is true; I had forgotten it. Very well: I have been complained of, tried, and found guilty—is that it?”

“Exactly. You are sentenced to two days’ solitary confinement in the college prison, and I am sent to fetch you.”

STUDENT. “Oh—I can’t go to-day.”

OFFICER. “If you please—why?”

STUDENT. “Because I’ve got an engagement.”

OFFICER. “To-morrow, then, perhaps?”

STUDENT. “No, I am going to the opera, to-morrow.”

OFFICER. “Could you come Friday?”

STUDENT. (Reflectively.) “Let me see—Friday—Friday. I don’t seem to have anything on hand Friday.”

OFFICER. “Then, if you please, I will expect you on Friday.”

STUDENT. “All right, I’ll come around Friday.”

OFFICER. “Thank you. Good day, sir.”

STUDENT. “Good day.”[24]

While this imaginary exchange is purposefully exaggerated, its tenor serves as a good indication of how students had come to view a stay at the Karzer in the second half of the nineteenth century, a period that saw them staging outrageous parodies of the rites associated with it. A 1908 compilation of student accounts of life at the University of Marburg includes a vignette about a remarkable procession that took place in 1905:

The procession displayed the transport of the academic criminal in a comical manner. At the front [marched] the color guard with a sign that revealed the goal of and reason for the trip. Then came a litter, escorted by two sinister officers of the law [and] carried by two porters, in which the delinquent, with a shaved head and in a blue prison jacket, received the homage of the masses. Bedding, clothes, books, pipes, and tobacco cases followed. A dignified quartet in evening dress paid their last respects, and a night watchman at the rear made just as much of an impression with his halberd and bugle as with his extraordinary physiognomy. Having arrived at the university building, the delinquent disappeared before the eyes of his attendants in order to move into his new apartment. … From on high, this man responded from his prison, in a voice choked with tears …, with words of farewell.[25]

The Heidelberg Karzer retains a mural of a similar parade on one of its walls, and Andrew Cowin’s Heidelberg Student Prison describes the images thus:

Instead of a horse and carriage, the smoking hero has to make do with a cart and a guard riding cockhorses, while a few necessities are pushed along in a pram. In fact, the ritual of taking a fraternity member to prison was often staged with great theatricality, sometimes with the victim being wrapped in chains while groups of mourners wailed pitifully.[26]

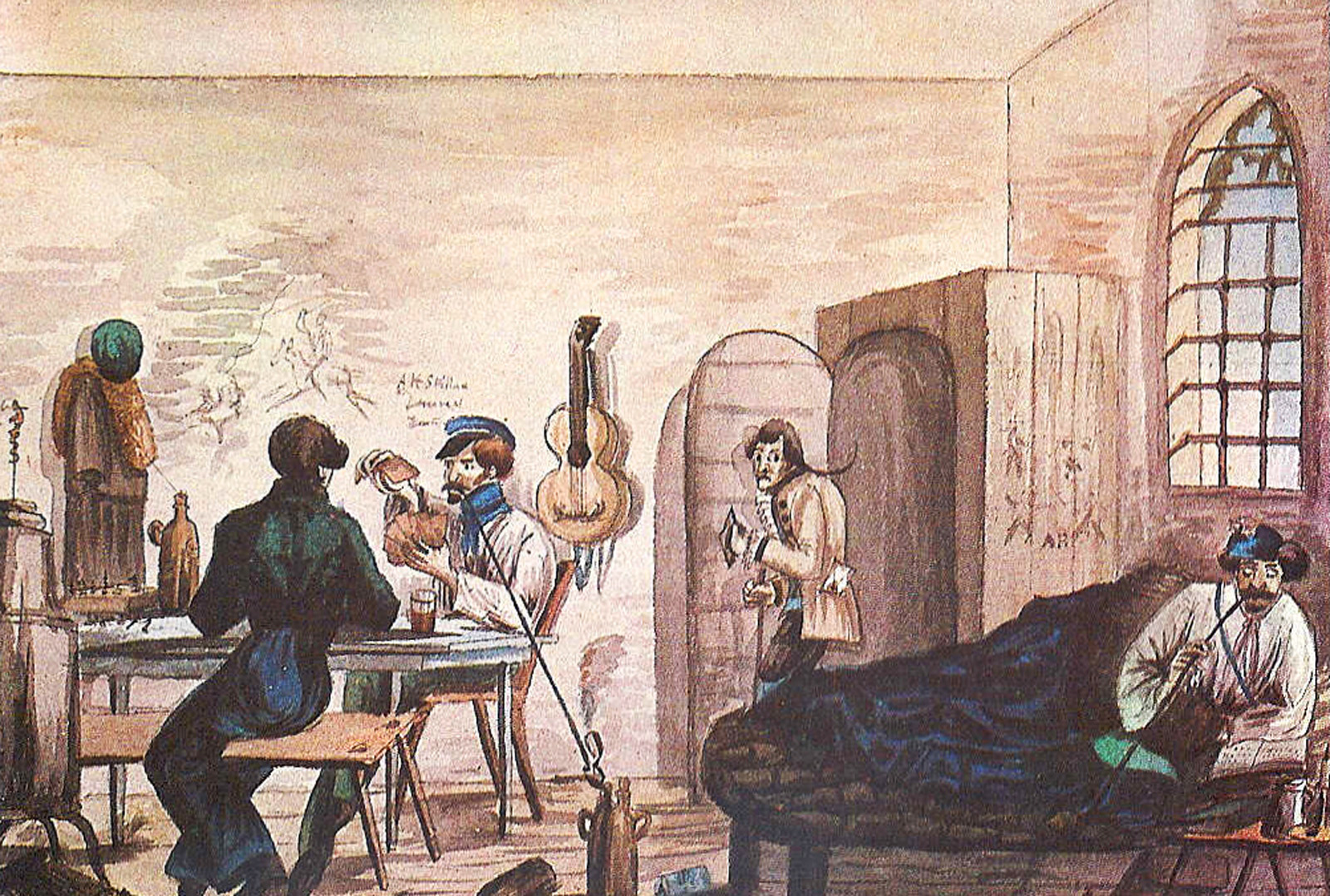

But the revelry did not end with the prisoner’s procession to his cell. Even when entirely isolated, many young men imprisoned in Karzer in the mid- to late 1800s managed to turn their sentences into festive occasions. In a 1907 article for Ludoviciana, a special publication created for the University of Giessen’s tricentennial, a Dr. Carl Dickoré-Lollar recounted his stay in the Giessen Karzer during his student days several decades before. Sometime during the mid-1800s, he was given a whopping three weeks for participating in a duel. No matter—a Karzer sentence was a cause for excitement, and he was determined to make the most of it. He arrived well prepared, writing,

I had my suitcase sent ahead, [filled] with books and drinks. My bedsheets were sent from home, and in order to not have to live out the long stretch between bare walls devoid of decoration, I brought my canary in its cage, some handsome pictures, potted flowers, long pipes, and other equipment with which I decorated my new home.[27]

The room was not designed for comfort. It was outfitted with simple wooden furniture, and the toilet, set into a closet, featured a hole small enough to quash “any hopes of using it as a means of escape.”[28] The windows were barred to prevent them from being used as conduits for flasks and boots full of wine brought to the prisoner by well-wishers. Students quickly developed a way around this problem, pulleying flasks up to the window and emptying them through the bars into water jugs. Presumably making use of this method, Dickoré-Lollar was delivered one flask of beer each day by his local barkeeper and another by a friend, in addition to the stash of drinks he had brought with him in his suitcase. Still more beer appeared when his brother joined him in the cell, sentenced to four days for having been his second in the duel. He managed to smuggle in several flasks of beer under his large coat, and they began drinking with gusto as a storm raged outside. When the caretaker paid them a call in the middle of the night, he nearly fell over in shock at the sight of the bacchanalian scene in the cell, but the brothers merely pulled him into their midst and got him so drunk that they had to carry him back to his quarters and put him to bed.[29]

Drinking was often accompanied by singing, another important part of nineteenth-century student life. Student organizations would publish song books (Kommersbücher) for their members that were studded with heavy, protruding Biernägel, or beer nails, that protected the book covers from tabletops sure to be slick with beer. Ownership of such books was common. In fact, a Kommersbuch was found among Friedrich Engels’s possessions when he died, and he claims to have attempted at one point during his exile in England to teach a canary the melody of “Gaudeamus Igitur,” an especially popular student song.[30] In The Student-Life of Germany, Howitt documents some of the other student drinking songs of the sort that appeared in Kommersbücher; their titles include “The Year Is Good, the Brown Beer Thrives,” “When Carousing, I Shall Die,” and “Crambambuli, That Is the Title.”[31] The right to sing these songs, it seems, was guarded jealously by their singers:

Should a Knote dare to sing a student song, he is to be well cudgeled; not so much on account of the excellence of the song, as on account of the audacity of the Philistine, presuming to desecrate songs sacred to the students, especially as it is impossible that he can have so much feeling as to appreciate the elegance and beauty of such songs.[32]

Howitt then goes on to document different phrases used to describe drunkenness among the students: “He is full and furious,” “He has got a bag-wig,” “He saw wooden cans in heaven,” “He has made himself a beard,” “His house is haunted,” “He is poodle thick,” “He goes as if all houses were his,” “He has had too much of a good thing,” “He has sprinkled his nose,” “He looks like a duck in thunder,” “He takes the church-spire for a toothpick.”[33] In the Karzer and its environs, bag-wigs abounded.

Such carousing must be understood in the context of another institution: German university brotherhoods (Burschenschaften), which had their roots in early German nationalist movements. At the turn of the nineteenth century, Germany was little more than a collection of small, loosely connected, self-governed states. Although Otto von Bismarck would not incorporate these states into a unified nation until 1871, the early years of the nineteenth century saw a nascent sense of German nationalism spreading among the bourgeoisie. This nationalism had a variety of sources, including, in some quarters, the desire to free the German states from Napoleonic rule.[34] Students were central actors in driving Napoleonic troops from Germany, as well as in early nationalist movements; German armies (containing many university students) managed to force Napoleon out in 1815, and the first Burschenschaft was founded in Jena the same year.

With Napoleon defeated, state governments turned their attention inward, targeting the rising tide of nationalism that they had begun to fear would lead to revolution. In 1819, the murder of playwright and Burschenschaft opponent August von Kotzebue by Burschenschaft member Karl Sand served as a welcome excuse for the German states to come together and ban student organizations wholesale, at which point they went underground.[35] Between 1819 and 1848, state governments pursued a relentless campaign against nationalists, and Burschenschaften members were barred from working, arrested, and driven into exile.[36] Students responded by flouting the laws and organizing frequent demonstrations. In 1828, a mob of two hundred students descended on the Heidelberg Karzer to free an inmate, and in 1832 students in the Palatinate region led impressive protests for national unification, culminating in widespread student mobilization in the revolutionary years of 1848–1849.[37]

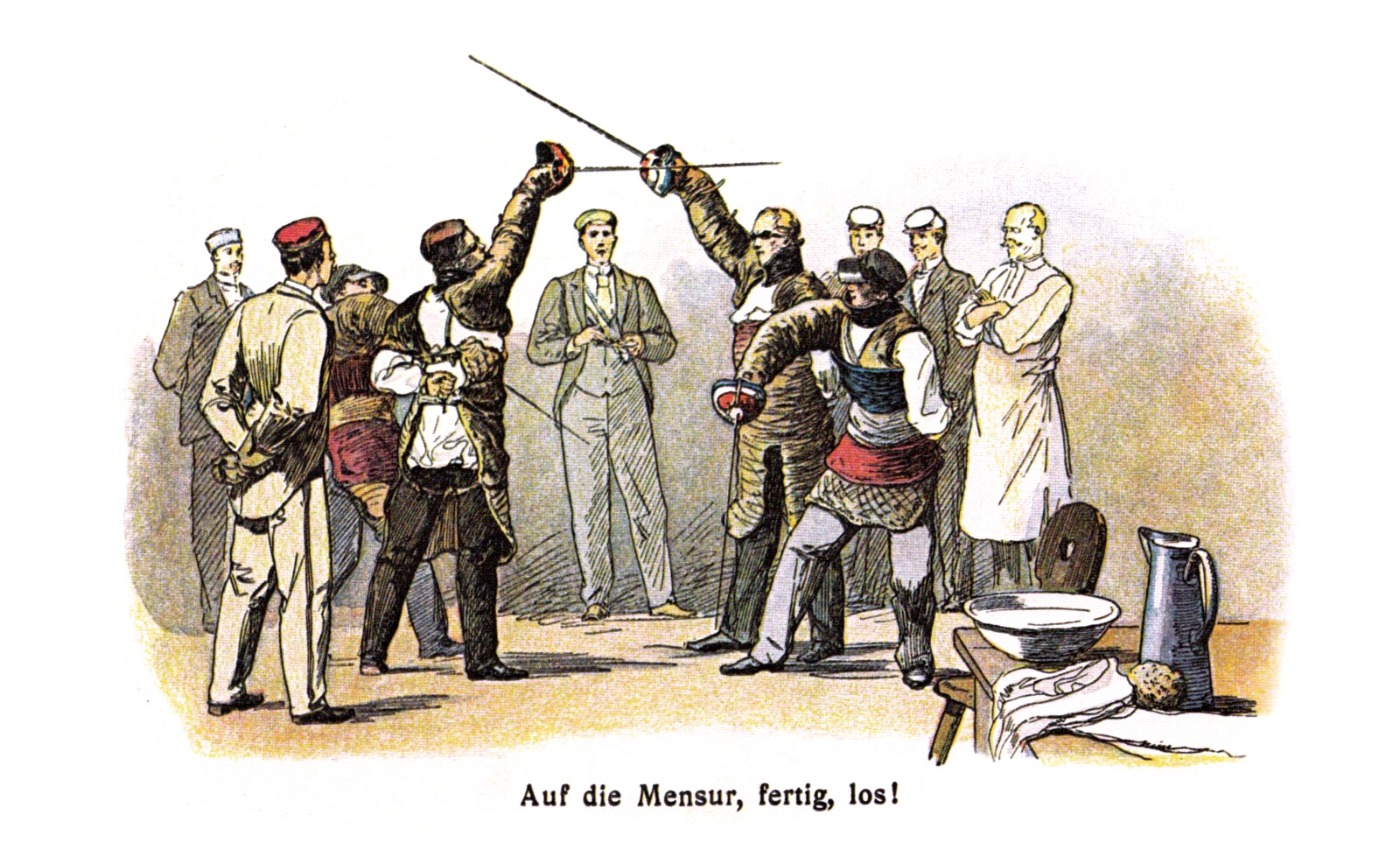

But the Burschenschaften were not all political agitation and liberal ideals. They were, at the end of the day, social organizations full of eighteen-year-old boys, and it was the Burschenschaften that encouraged a great deal of the drunken and lewd behavior that landed students in the Karzer in the first place. Burschenschaften have historically required that their members engage in a certain number of fencing duels, or Mensuren, in order to maintain their membership, and much of the dueling that led to Karzer sentences likely took place as part of this requirement.[38] Thus, it is unsurprising that Burschenschaft coats of arms feature prominently in the graffiti on the walls of German Karzer. The Heidelberg Karzer even features a coat of arms for a fake Burschenschaft named Karzeronia, created by members of the Suevia and Guestphalia Burschenschaften.[39]

Modern Burschenschaften are, for the most part, highly conservative student groups that often overlap with far-right extremist movements. Although technically banned under the Nazi regime in 1935, many of them had developed a commitment to anti-Semitic ideals in the late nineteenth century, and it was easy enough for them to simply rename themselves and take on a new life as NS-Kameradschaften, a common type of Nazi social organization. After the end of the war, the Americans and British explicitly banned the resurrection of Burschenschaften on the basis of their ties to National Socialism, but the groups simply rebranded themselves again, this time as “friendship clubs” or “tavern societies,” until the newly founded Federal Republic of Germany lifted the ban in 1950. In today’s Germany, the right-wing leanings of Burschenschaften still go far beyond mere nationalism. In 2011, the Deutsche Burschenschaft, the oldest and largest umbrella organization of fraternities, caused a scandal when it established an ethnic requirement for membership: to join, one had to be descended predominantly from European ancestors. Merely possessing German citizenship did not suffice, and around the time that it issued this edict, the organization threatened to expel their Mannheim chapter for including a German student of Chinese descent in their membership.[40]

This brings up an important point: Karzer were ultimately as much an instrument of privilege as of punishment, especially over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Young men at German universities could expect far better treatment than their working-class counterparts when it came to punishment for the same crimes and infractions. It was easy for these young men to treat their punishment as a farce because it was, in fact, a farce. In the meantime, beggars were being thrown into workhouses as punishment for their poverty, a practice that continued through the early years of the twentieth century. And the Karzer was not only a playground for the middle class and the rich, but specifically for middle-class and rich men. Women only appeared in Karzer in wall inscriptions lamenting the absence of girlfriends and in murals depicting nude, large-breasted female bodies. Save some exceptional cases, it was not until the early twentieth century that women students were even allowed to study at German universities, and by that point, Karzer had been all but phased out.

The Karzer, then, is very much a relic of a bygone age. As delightful and fantastical as many of its stories may be, it belongs to an order of things that should have been left behind long ago, but that has regrettably persisted in more ways than one. The German educational system was designed from the start to maintain strict forms of class stratification, and in many parts of the country, secondary schooling is still split into three tiers—Hauptschule, Realschule, and Gymnasium—where only Gymnasium students are expected and prepared to continue their education at university. Students of color are kept almost entirely out of Gymnasien; Uğur Şahin, one of the two Turkish-German immunologists who developed the mRNA technology responsible for inoculating large swaths of the world against Covid, was told by his teacher that he could not apply to Gymnasium.[41] Stories like this are far from uncommon.

Of course, this type of racialized and classed social stratification is not unique to Germany. It is also a key feature of contemporary American education, from kindergarten all the way through university (the latter, perhaps not so coincidentally, was initially modeled on the German university system). In the 1950s, the University of Chicago had the dubious distinction of being the first American university to build an expansive private police force. Today, it is home to the second-largest private police force in the world (topped only by the Vatican’s Gendarmerie), which has jurisdiction over entire Chicago neighborhoods and is not subject to Illinois’s Freedom of Information Act.[42] Like the German academic judiciaries that once meted out Karzer sentences, such private campus police forces were created to cushion students against the rougher treatment inflicted on unaffiliated locals. In practice, however, with elite campuses now less racially and economically uniform, university police forces have often ended up offering this protection unequally, with students of color, student-activists (who are often disproportionately working class), and visibly queer students hassled, threatened, or met with outright violence.[43] In the meantime, byzantine academic juridical councils protect rapists from facing consequences for their actions and ensure that powerful professors who harass and assault students are permitted to keep their jobs. Elite universities in the United States, in other words, have maintained campus relations that would in many ways be familiar to a nineteenth-century German university student. Whether such universities are capable of fundamental change or whether they will continue to maintain tyrannical police forces, strategically inaccessible bureaucracies, and populations of young fraternity brothers nourished on impunity remains to be seen.

- Ernst Eckstein, The Visit to the Cells, trans. Sophie F. J. Veitch (London: Provost, 1876), pp. 8–12. Available at archive.org/details/visittocells00veitgoog. The original German-language version of the story, which appeared in 1872 in serial format in issues 1427, 1428, and 1429 of the magazine Fliegende Blätter, is available at digipress.digitale-sammlungen.de/calendar/1872/newspaper/bsbmult00000628. The German word Karzer is a Germanization of the Latin word carcer, meaning prison. The spellings Karzer and Carcer are often used interchangeably in historical German-language documents, and the spellings vary in different versions of Eckstein’s book. It should be noted that the singular and plural forms of the word Karzer are identical.

- Ernst Eckstein, The Visit to the Cells, p. 28.

- Ibid., pp. 29–46.

- Ibid., p. 51.

- In comparison with the wealth of information available on university Karzer, there is little available on secondary school (Gymnasium) Karzer, especially with regard to legal matters; as such, I am able to make legal generalizations about university Karzer only.

- Andrew Cowin, Heidelberg Student Prison (Heidelberg, Germany: Heidelberg University, 2011), p. 6.

- See Leipzig University Archives, “Karzerstrafen,” n.d. Available at ual.archiv.uni-leipzig.de/karzerstrafen.php. My translation.

- See University of Würzburg Archives, “Gerichtsbarkeit,” n.d. Available at uni-wuerzburg.de/en/uniarchiv/ausstellungen/insignienundgeschichtsbewussts/gerichtsbarkeit.

- Disenrollment record for Karl Marx quoted in Carsten Bernoth, “Zelle mit Aussicht: Der Bonner Karzer 1818–1899,” Bonner Rechtsjournal, no. 2 (February 2010), p. 260. Available at bonner-rechtsjournal.de/fileadmin/pdf/Artikel/2010_02/BRJ_260_2010_Bernoth.pdf. My translation.

- Ken Ird, curator, University of Tartu Museum, email to the author, 12 November 2021.

- See University of Coimbra, “Academic Prison,” n.d. The archived webpage is available at web.archive.org/web/20230203160035/http://visituc.uc.pt/en/prision.

- For a history of this shift in penal practices, see Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Vintage Books, 1995).

- Lukas Ruprecht Herbert, Die akademische Gerichtsbarkeit der Universität Heidelberg (Heidelberg, Germany: Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, 2018), p. 76.

- Ibid., p. 78.

- There is actually some uncertainty as to the original number of cells. While both Andrew Cowin’s Heidelberg Student Prison and Lukas Ruprecht Herbert’s Die akademische Gerichtbarkeit settle on two, Cowin mentions that there is “a document of 1806 [that] speaks of three cells.” See Heidelberg Student Prison, p. 18.

- Andrew Cowin, Heidelberg Student Prison, p. 18.

- Ibid., p. 20.

- Ibid., p. 27. The first three are all names of famous palaces; about the fourth, Villa Trall, Cowin writes: “The Villa Trall (formerly called Vivat nox, i.e., ‘hail the night’) derives its name from the student word for silliness and nonsense, Trall.”

- William Howitt, The Student-Life of Germany (Philadelphia: Carey and Hart, 1842), p. 152.

- See plate 26 in Hans Günther Bickert and Norbert Nail, Marburger Karzer-Buch: Kleine Kulturgeschichte des Universitätsgefängnisses (Marburg, Germany: Jonas Verlag, 2013), p. 48. My translation.

- Mark Twain, “Appendix C,” A Tramp Abroad, vol 2. (Leipzig, Germany: Bernhard Tauchnitz, 1880), pp. 248–249. The second of the three inscriptions is rendered in the original German in the book, and is my translation. Twain suggests that the student who wrote it had committed an infraction merely because he was curious about what it was like to spend time in the Karzer.

- Ibid., p. 250.

- The legal jurisdiction of universities had traditionally extended to those categorized as “related to the university,” and as such included the wives, children, and widows of university personnel. For more on the 1877 law, see Philipps University of Marburg Archives, “Zur Handhabung der Disziplin: Der Marburger Karzer,” n.d. Available at ausstellungen.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/karzer/.

- Mark Twain, “Appendix C,” A Tramp Abroad, pp. 245–246.

- Ludwig Müller, Marburger Studenten-Erinnerungen (Marburg, Germany: Universitäts-Buchdruckerei von Johann August Koch, 1908), pp. 99–100.

- Andrew Cowin, Heidelberg Student Prison, p. 29.

- Carl Dickoré-Lollar, “Im Gießener Karzer,” Ludoviciana: Festzeitung zur dritten Jahrhundertfeier der Universität Gießen, no. 4 (Summer 1907), p. 61. Available at geb.uni-giessen.de/geb/volltexte/2005/2611/pdf/Ludo4-Dickore-60-62.pdf. My translation.

- Ibid. My translation.

- Ibid.

- Hans Günther Bickert and Norbert Nail, Marburger Karzer-Buch, p. 58.

- William Howitt, The Student-Life of Germany, p. 292.

- Ibid., p. 289. Howitt draws this quotation from a late eighteenth-century text titled Dissertatio de norma actionum studiosorum seu von dem Burschen-Comment, which was published under the pseudonym Martialis Schluck. Knote was a slang word used by students to designate those they considered to be of a lower status.

- Ibid., pp. 296–297.

- See Christian Jansen, “The Formation of German Nationalism, 1740–1850,” in The Oxford Handbook of Modern German History, ed. Helmut Walser Smith (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 244.

- Mary Fulbrook, A Concise History of Germany, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), pp. 106–107.

- Hans Günther Bickert and Norbert Nail, Marburger Karzer-Buch, p. 67. The so-called “Demagogue Persecution” also required that any book less than 320 pages in length be submitted to the censors prior to publication, a policy designed to prevent the printing of political pamphlets. To get around this, determined publishers would print books with tiny pages and enormous print in order to stretch out tracts to just over this limit. See Mary Fulbrook, A Concise History of Germany, p. 107.

- Andrew Cowin, Heidelberg Student Prison, pp. 10–11.

- These mandatory Mensuren were duels in every respect but one: the aim was not to win (opponents were generally fellow brothers in one’s Burschenschaft), but to prove that one was able to engage in a risky, stressful situation while still upholding the brotherhood’s code of gentlemanly conduct. Ideally, one would—at least in the early days of the practice—also sustain a wound that would result in a facial scar.

- Information in the Leipzig archives suggests that the associations were also at times involved in strange, cross-Burschenschaft actions. In 1866, ten young men seem to have been under investigation for having assisted in burying a victim of suicide. Representatives of eight different Burschenschaften—Misnia, Dresdensia, Lusatia, Saxonia, Guestphalia, Germania, Arminia, and Alemannia—were given Karzer sentences for their organizations’ involvement in these events. See Leipzig University Archives, “Karzerstrafen.”

- Florian Diekmann, “Burschenschafter streiten über ‘Ariernachweis’” (online only), Der Spiegel, 15 June 2011. Available at spiegel.de/lebenundlernen/uni/rechtsruck-im-dachverband-burschenschafter-streiten-ueber-ariernachweis-a-767788.html.

- See Ernst Dieter Rossmann and Behrang Samsami, “Gemeinsam denken,” Der Freitag (Berlin), 2 December 2020. Available at freitag.de/autoren/behrang-samsami/gemeinsam-denken. An article in Monocle notes that Şahin was allowed to apply to Gymnasium only after a white German neighbor intervened with officials at his school. See Aaron Burnett, “Fractured State” (online only), Monocle, 12 January 2023. Available at monocle.com/minute/2023/01/12.

- See Nathalie Baptiste, “Campus Cops: Authority without Accountability” (online), The American Prospect, 2 November 2015. Available at prospect.org/civil-rights/campus-cops-authority-without-accountability.

- Ibid. Baptiste mentions a 2006 incident at the University of California Los Angeles in which Mostafa Tabatabainejad, a student of Iranian descent, was tasered by campus police while studying in the university library, as well as a 2015 incident in which Tahj Blow, a Black Yale undergraduate (and son of New York Times columnist Charles Blow), was forced to the ground at gunpoint by a campus police officer who assumed he was not a student. Similar events happen all the time; in 2019, Barnard College officers refused to let a Black student enter the library, and in 2018, officers at Yale harassed a Black graduate student who had fallen asleep in a common room of her own dorm building. The list goes on.

Reed McConnell is a writer and anthropologist whose work has appeared in The Baffler, Frieze, n+1, Tagvverk, and The Point, among other publications. She holds an MA in cultural theory and history from Humboldt University and is a PhD candidate in anthropology at the University of Chicago.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.