Crash Covers

Mail trouble

Jeffrey Kastner

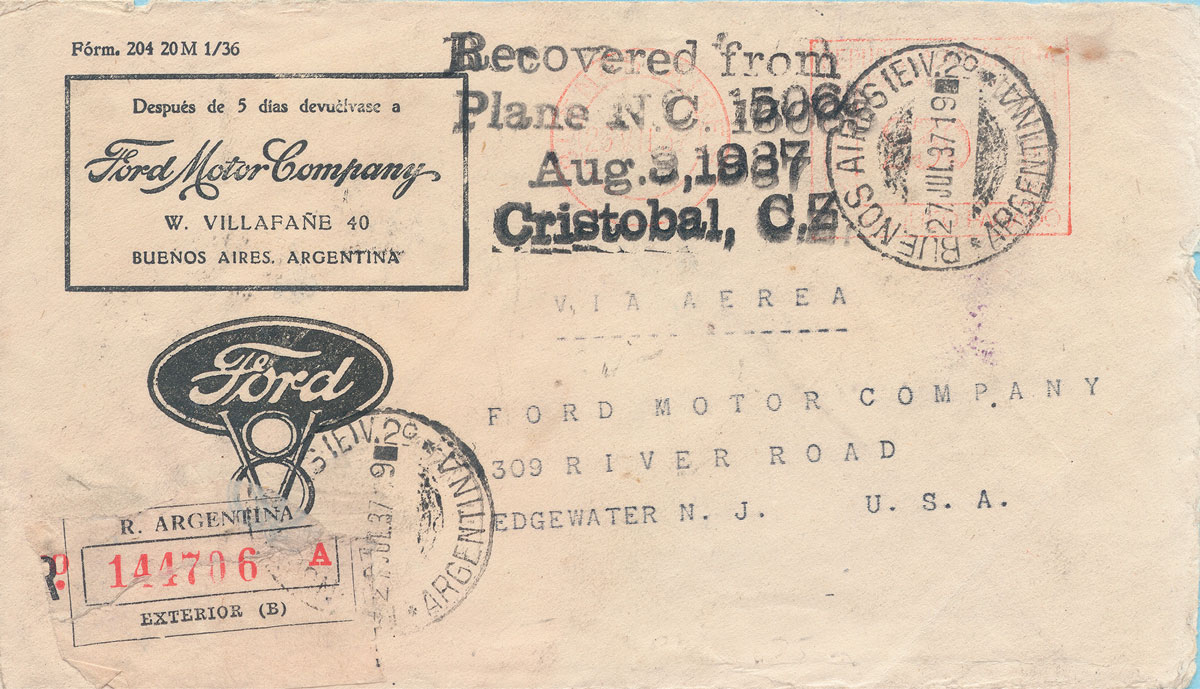

On an early August day in 1937, a plane trying to make a landing in what was then known as the Panama Canal Zone hit heavy weather and crashed in the waters of the Mosquito Gulf. Among the items on board later fished out of the southern Caribbean was some 43 pounds of mail, which was taken to a bakery in the nearby coastal town of Cristoba to dry out and then returned to the local post office. Before sending it off again to its intended recipients, local postal authorities stamped each item with a simple four-line message explaining its detour: “Recovered from / Plane N.C. 15065 / Aug. 3, 1937 / Cristobal, C.Z.”

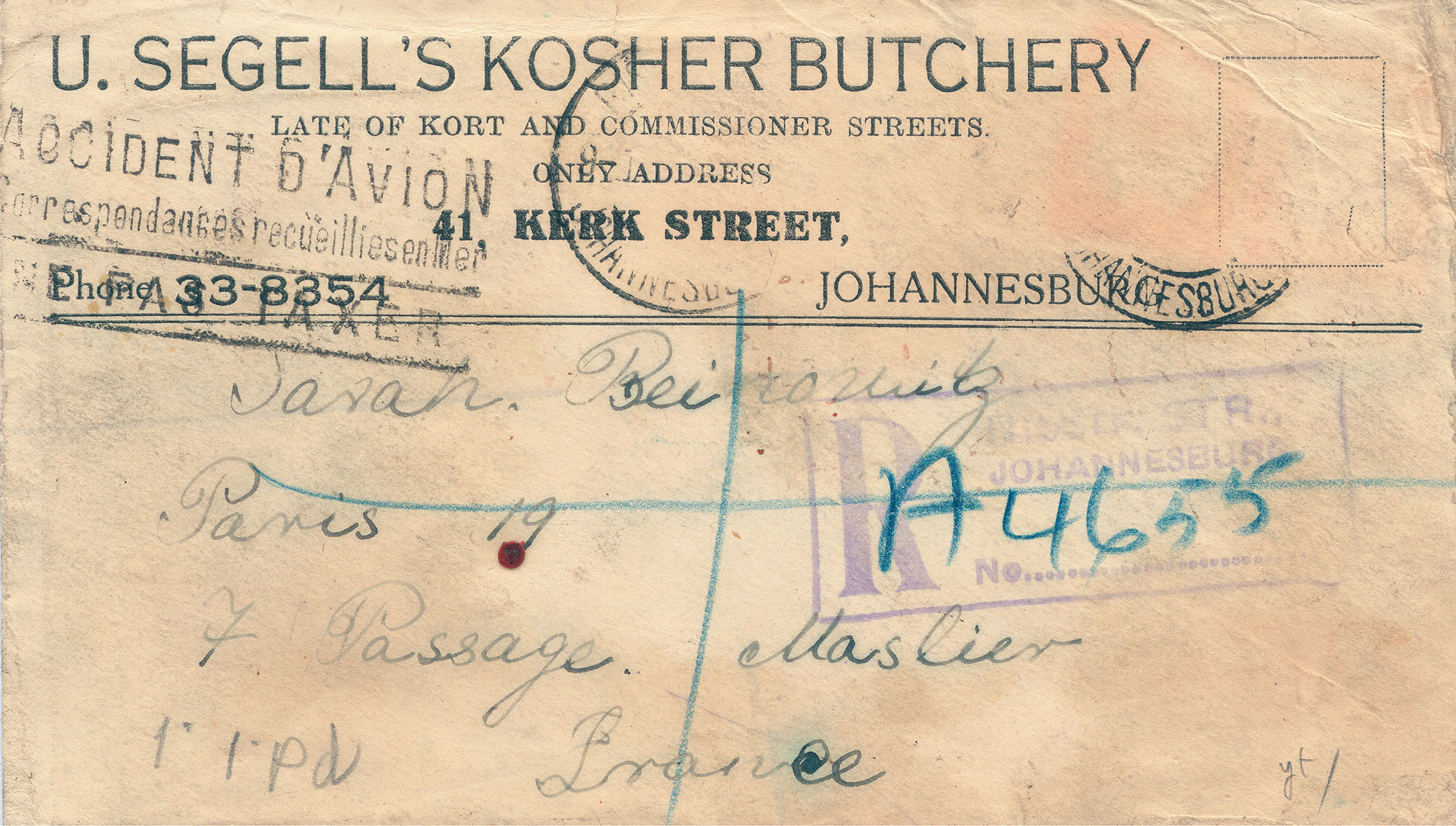

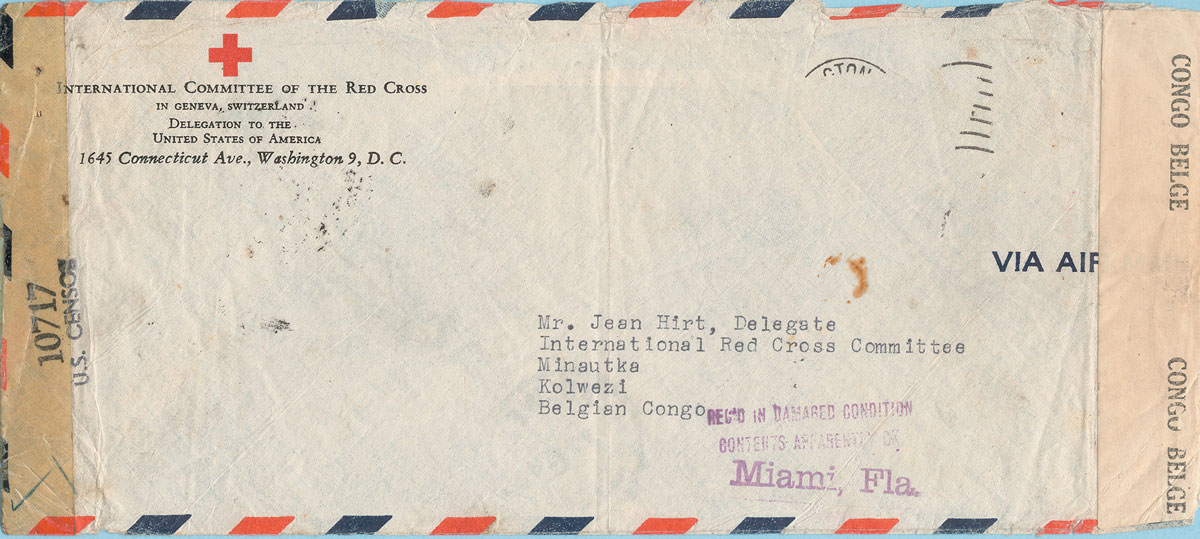

Since the first fixed-wing aircraft on an official mail-carrying flight successfully traveled the five miles between Allahabad and Naini Junction in India on 18 February 1911, millions of airplanes have safely and reliably carried billions of items around the globe via airmail. However, for the collector of “wreck mail” (a branch of philately dealing in memorabilia from various misadventures that have interrupted scheduled mail service, whether by land, by sea or, in this case, by air) this rule is less interesting than the rare exceptions to it. Kendall Sanford, a Geneva-based philatelist, has amassed a large number of what are commonly referred to as airmail crash covers—envelopes that bear damage, incidental markings, or official cachets resulting from or related to air accidents—specifically those involving either Pan American or Imperial Airways, Britain’s first overseas international carrier. The examples below—including a letter from an office of the Ford Motor Company in Buenos Aires to another in Edgewater, New Jersey, recovered from the Cristobal disaster—come from his collection.

Few activities in our everyday life represent as much of a leap of faith as the act of putting something in the mail. We readily consign materials constituting the full range of our relationships and obligations—from birthday cards to bill payments—to the maw of a mechanism we only vaguely understand; we buy into, without reservation, the idea that everything will turn out fine in the end. And it is remarkable how often it does. Important pieces of correspondence almost always get where they’re going; private information exchanged between people typically stays private; items of value consistently reach their destinations unmolested. No doubt it is this sense of inevitability about the mail, the generally high degree of assurance that usually accompanies its use—as well as our changing relationship to it in an increasingly digital age—that makes its rare failures all the more poignant. And it is this intersection between the rare and the poignant that makes such philatelic artifacts, indeed all such “souvenirs,” so prized.

As Susan Stewart, the author of On Longing, has observed, the souvenir “distinguishes experiences. We do not need or desire souvenirs of events that are repeatable,” she writes. “Rather we need and desire souvenirs of events that are reportable, events whose materiality has escaped us, events that thereby exist only through the invention of narrative.” Our experience of mail tends to be point-to-point: we know origin and terminus, but what lies between remains a mystery. Crash covers expose the shape of the network, open a window on a usually clandestine system, and invite the introduction of narrative. And there surely is something of both triumph and calamity in them—only by being found did they come to be celebrated; only by being lost did they come to be desired. Their status as objects is based on a delicate calibration of success and failure, and on the uncanny way they carry the evidence for both in their very materiality—fulfillment and flaw written together like a postscript on a faded piece of stationery.

Cabinet wishes to thank Kendall Sanford for his assistance with this article. For more information, see his website at http://aerophilately.net

Jeffrey Kastner is a New York–based writer and an editor of Cabinet.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.