Inciting Genocide: An Interview with Michael Sfard

The legal case against Israel’s Channel 14

Sina Najafi, George Prochnik, and Michael Sfard

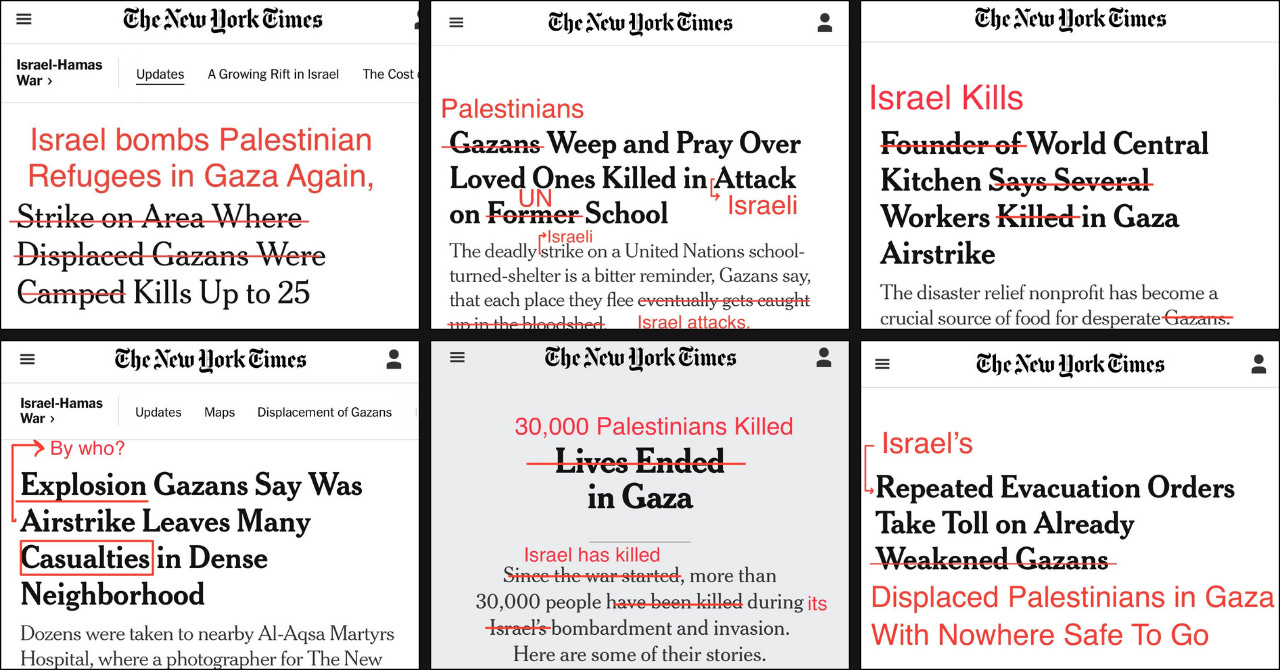

In the past two years, a number of notable reports in scholarly publications and in independent media sources have begun to assess the ways in which the almost universal failure of journalistic practices and ethics at prominent Western news organizations has abetted Israel’s genocide in Gaza. These investigations detail how the mainstream media, ranging from The New York Times to the BBC, have helped manufacture consent for the genocide through an array of mechanisms, including the routine dehumanization of Palestinians, overwhelming reliance on Israeli governmental perspectives, an almost total disregard for fact-checking, rhetorical sleights-of-hand, and the habitual exclusion of voices critical of Israel. Alongside these efforts, a growing number of human rights lawyers, including Francesca Albanese, have asked that certain Western media organizations be investigated for their complicity in the offenses outlined in the 1948 UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. Though much more rare, similar criticism has also been voiced within Israel. The investigative news platform The Seventh Eye has repeatedly documented instances of actionable media incitement, and a December 2023 letter signed by fifteen prominent Israelis—among them academics and former ambassadors—accusing the judiciary of ignoring genocidal public statements included examples of such speech on television programs.

In September 2024, news emerged that one of Israel’s foremost human rights lawyers, Michael Sfard, had submitted, along with two colleagues, a letter on behalf of three Israeli human rights organizations to Gali Baharav-Miara, the attorney general, asking that she investigate Israel’s Channel 14. The letter detailed how the channel—home to some of the most violent rhetoric demonizing and delegitimizing Palestinians—was potentially guilty of incitement to genocide, one of the most serious crimes recognized under Israeli law, as well as incitement to violence and incitement to racism. An accompanying document meticulously charted more than two hundred and fifty instances of allegedly genocidal speech aired on the channel. A second letter to the authority responsible for regulating commercial broadcasts requested that it investigate Channel 14 for violating the terms of its license. After months of inaction on the part of the attorney general, Sfard filed in May 2025 a petition with the country’s High Court seeking an injunction against the attorney general, the state attorney, and the police for failing to conduct an investigation into the broadcasts, as mandated by Israeli law.

There are a number of precedents within international law for examining the role that mediatized words and images can play both in inciting genocide and in positioning it as an acceptable response to the unwanted presence of entire populations. The crime of genocide had not yet been legally codified at the time of the Nuremberg trials (1945–1946), which instead charged the accused with “crimes against humanity,” among other atrocities. Notably, among the indicted stood Julius Streicher, founder and publisher from 1923 to 1945 of the virulently anti-Semitic weekly newspaper Der Stürmer. The judgment against him, delivered on 1 October 1946, stated: “In his speeches and articles, week after week, month after month, he infected the German mind with the virus of anti-Semitism, and incited the German people to active persecution.”

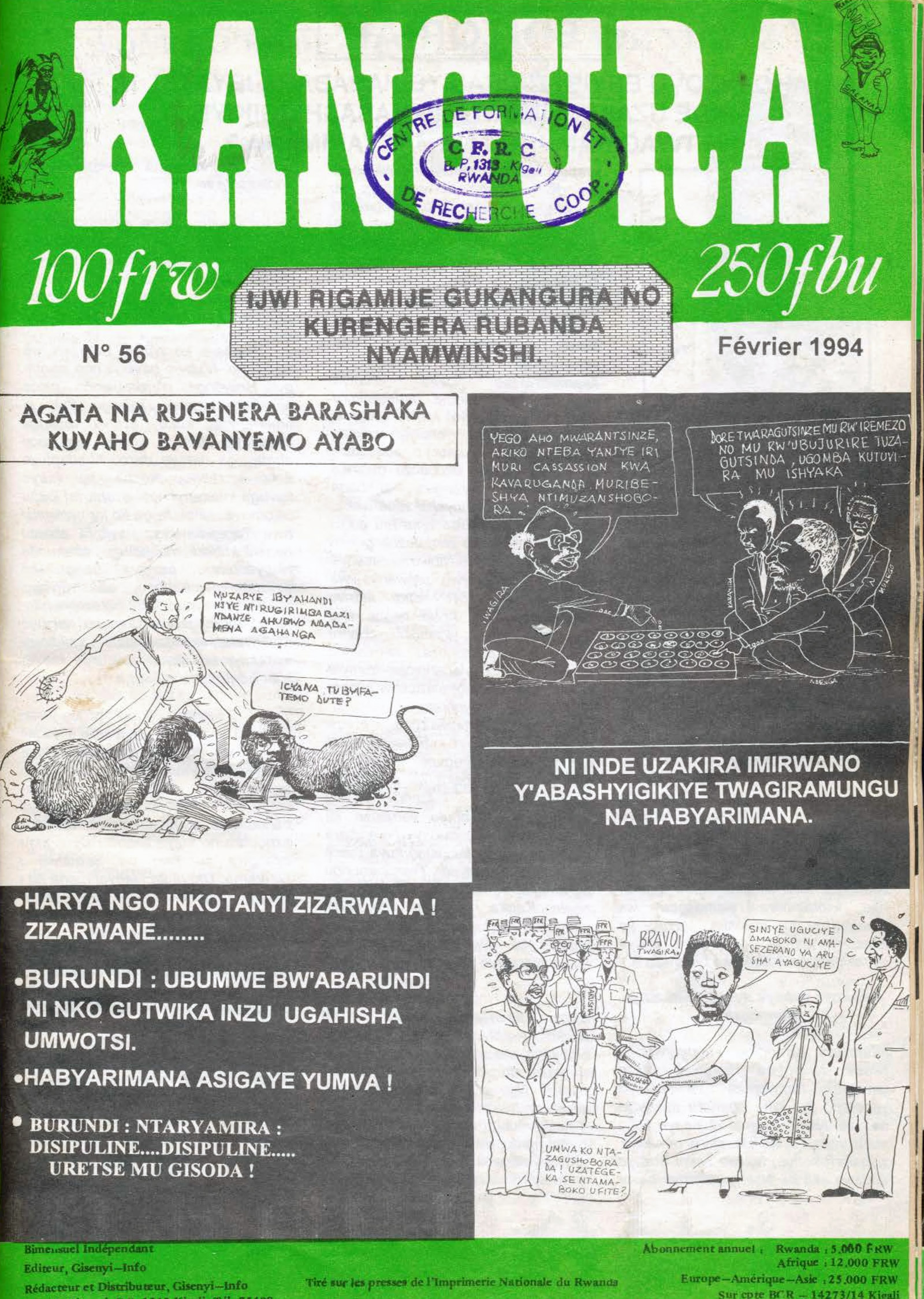

The most important legal precedent, however, was set by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, the first in history to deliver verdicts against individuals for crimes outlined in the 1948 genocide convention. Established by the United Nations in 1995 to prosecute those responsible for the murder of more than one million Tutsis over the course of some hundred days the year before, the tribunal finally sentenced sixty-two individuals, including three who collectively constituted the so-called media case: Jean-Bosco Barayagwiza and Ferdinand Nahimana, members of the committee that founded the notorious Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines, and Hassan Ngeze, founder and editor-in-chief of Kangura magazine. The charges faced by all three included that of “direct and public incitement to commit genocide.” Musician and singer Simon Bikindi, whose incendiary songs were often played on the radio, was also sentenced for the same crime.

In July 2025, Cabinet conducted an interview with Michael Sfard to discuss the legal, ethical, and political ramifications of the petition, both within Israel and internationally, as well as how it should be understood within the postwar framework of human rights. While editing the wide-ranging discussion over the next several months, changes were made as new information about the status of the petition became available. Sfard’s final additions and amendments to the interview were made in late January 2026.

CABINET: Perhaps we can start with an introduction to the background of the case against Channel 14.

MICHAEL SFARD: First of all, it’s important to understand that Channel 14 was born in sin. When it began in 2014, it had a license to broadcast material dedicated exclusively to traditional Jewish heritage themes, but it violated the terms and began to air news and programs of a political nature. At first, it was fined but then in 2018, the law was amended and its license expanded to allow it to broadcast news programs. So now, through this murky process, we have effectively a new channel that is allowed to broadcast news and current affairs, and it gradually evolved into the principal megaphone for the Israeli far right—that’s to say, the Messianic, ethnonationalist, Zionist right. And it came to be known as the Bibi channel, the channel voicing Netanyahu’s positions, providing unlimited airtime to him and his allies, while simultaneously fighting against those whom he perceives to be political rivals—not only on the left, his opponents on the other side of the political aisle, but also his rivals from within the right-leaning parties.

Ever since this transition, the channel has only grown to be more and more popular, its success fueled by its having adopted an editorial line that made it a very, very blunt platform for the expression of all sorts of politically incorrect positions. For instance, along with its nationalistic politics, Channel 14 is also a place where opposition to affording protections and rights to the LGBTQ community is given a stage.

We understand it’s the second-most popular channel in Israel.

Yes—since October 7th, that’s the case, at least during some hours of the day. Channel 14 began as a very peripheral channel and remained so for a long time with very low viewership. Gradually, it became what we initially labeled the “Israeli Fox News,” but I now understand what an understatement of the problem that was. In fact, it’s much worse; it’s Breitbart—something pandering to the conspiracy-driven radical right. What’s even more pernicious is that when they adopted this editorial character of being very “gloves-off” and shameless—of saying things that wouldn’t be said on other channels and ferociously inciting against groups within Israeli society, in particular against the Palestinians, of course—they did so in a notably seductive fashion. The channel employs TV personalities who are often highly charismatic and, critically, have a sense of humor. They make fun entertainment out of the news, while constantly sending a message to their viewership, “We are the best, we are the Jews!” All of this together was what made Channel 14 what it is today, a platform that basically serves as the hub for two communities: One is the staunch “Bibi-ist” group, which is composed of the populist camp that follows Netanyahu as a supreme leader, some of whom even see him as sent to the Jewish people from God. The other group is from the religious Zionist settlement movement. This community is not “Bibi-ist”; they’re not populists. They’re completely ideological. They have a very deeply held, genuinely devilish ideology, and Channel 14 is also their home.

I should add that for years, the channel has been enjoying all sorts of exemptions from the regulatory and financial burdens that other channels bear, and there are all kinds of excuses for this special treatment.

Do you feel that the hiring and promotion of Yinon Magal, who anchors the panel discussion HaPatriotim, has been partly responsible for shaping the channel’s profile as a showcase for something like feel-good brutal nationalism?

I’m not an expert on media, or on Channel 14 and its tainted history. I know the channel because of my own work supporting the human rights of Israel’s vulnerable populations, in particular the Palestinians. But from my perspective as an Israeli citizen who consumes Israeli media, yes, I think that those individuals are, as I mentioned, extremely charismatic and sharp. You can see equivalents in the American media landscape on the extreme right within the MAGA movement. Although I try not to succumb to that entertainment factor, it’s simply the case that some of them are really good in the sense that they put on a good show. They’re snappy and articulate, they know how to make an argument, and they are compelling. The Israeli and US reactionary media ecospheres championing these two regimes are very similar in that sense.

You’re making us think of Tucker Carlson’s devastating interview of Senator Ted Cruz in June 2025.

Yes. How did I react to that spectacle? I actually shared the Carlson video on my own social media feeds; I’ve never done that before with material from these sorts of sources.

Thinking of how slick these shows are, and of how effective their messaging is, we want to ask you later specifically about the role of humor in their approach. The use of humor to normalize, and even glamorize, exterminationist discourse is, of course, not a new tactic. It was also a strategy used at Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines, the infamous Rwandan radio station. But maybe we can first delve a little into the petition itself and how the three NGOs on whose behalf you’re advocating came together.

Already in the early days of the war on Gaza, a group of activists sensed that something different was happening. Something unlike what we had seen in previous security crises or military operations—a shift in the collective psychological state. They recognized that this moment was being exploited to normalize violence in ways we had not witnessed before. The normalization, dehumanization, and incitement to war crimes and genocide were everywhere—not only on Channel 14, but also echoed by public officials, cultural and artistic figures, and even on other television channels.

The focus on Channel 14 did not emerge immediately. It followed earlier initiatives in this field—including a letter from Holocaust and Jewish Studies scholars to Yad Vashem calling for public criticism of the growing incitement, and even a letter from former senior officials to the attorney general. Yet, as we delved deeper, it became clear that Channel 14 was distinct—unique in its scale, in the bluntness and directness of its most extreme statements, in the almost complete absence of dissenting voices in its studios, in the uniformity of its messaging throughout the day, and in its deliberate amplification of incitement on social media.

There’s a famous sketch from the mid-1990s produced by a very well-known Israeli theater group, the Ha-Hamishia Hakamerit, the “Cameric Five.” The sketch portrays a children’s television channel that receives a call from a young student who’s been asked to write a homework essay she’s finding difficult. Asked by the host what the topic is, she answers: ‘The Assassination of Yitzhak Rabin: Pros and Cons.’” At the time the skit was aired, this was seen as crazy, of course—outrageous satire that would never happen in reality. But after October 7th, we actually did have discussions that raised questions like, “Mass Killing: Pros and Cons” or “Creating Humanitarian Disaster in Gaza: Pros and Cons.”

The activists recognized that Channel 14 was an especially powerful and influential tool in the hands of those seeking to promote such agendas, and that confronting it required a broad and coordinated response—one far more comprehensive than anything undertaken before. This realization brought together three organizations—The Democratic Bloc, Zulat, and the Movement for Fair Regulation—who jointly developed a collaborative effort that deepened their understanding of the severity of the situation and led to concrete actions to curb incitement and prevent the escalation of hate-driven violence.

We’d like to go back to your statement that Channel 14 is not alone in its incitement, despite its uniquely systematic approach. In November 2023, an Israeli broadcaster posted a video on its social media, before taking it down in response to criticism, of a group of Israeli children singing in support of what was happening in Gaza. Its lyrics had lines such as, “Within a year, we will eliminate them and we will return to plough our fields.” While preparing for this interview, we watched it again, sure that it must have been Channel 14, but it was actually Kan, the public TV station. And there have been many other breaches of journalistic standards that turned out to be on Channel 12 or 13—for instance, a reporter from Channel 12 accepting an invitation from the army to blow up a building in southern Lebanon live on camera. But as you say, the question of systematic incitement is the important thing in the petition.

What has been your legal strategy once you and the group settled on a specific set of complaints? We understand that the petition comprises three different charges of incitement: incitement to genocide, which is, of course, the most important one; incitement to violence; and incitement to racism. Could you tell us about the three separate strands of the petition? It might be helpful here if you could also explain the relationship between the 1950 Israeli law on genocide that you invoke in the petition and the United Nations’s 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

There are several challenges in a case like this. First of all, I want to say something about strategy. It was never our intention at any point to launch a criminal investigation against a specific individual for a specific statement. It would be important, of course, that such investigations be undertaken, but that’s not what this case is about. This case has much larger aspirations. We look at the aggregated incitement statements, and we say that in this instance, the sum is far greater than its individual parts—and far worse. That’s why it’s so similar to the Rwandan radio case, in which some of the defendants were not those making the inciting statements, but their guilt stemmed from their editorial positions and the overall, systemic project of incitement that the channel executed.

Establishing the difference between a litigation dealing with a specific statement by a specific individual and one alleging that there is a system devoted to constant incitement was our first challenge because we wanted to make sure that the court wouldn’t break the case into a hundred small cases. Secondly, there was the challenge of translating the tenets of international law into domestic Israeli law. Because under the terms of international law, the incitement we see on Channel 14 is not divided into the three elements in our petition. Incitement to violence and incitement to racism are foreign to international criminal law. The only category that is identical in both sets of law is, in fact, incitement to genocide.

The reason for this is twofold. First of all, let’s say something about incitement. Incitement to commit a crime is not a crime in general unless it is explicitly defined as such with regards to a specific offense. Typically, once some activity is designated as illegal, then assisting, aiding, and abetting or soliciting that offense is also a crime. If you solicit a crime, no matter what the crime is, then the solicitation is a crime in and of itself. But incitement is not the same. In the case of incitement, there must be a specific standard that says incitement to this particular act is a crime. Why? Because of the importance of freedom of speech. The crimes of solicitation and aiding and abetting apply to particular activities that are about to occur. You are not aiding and abetting crimes in general; you are aiding and abetting, for example, the murder that is going to be committed tomorrow against a certain individual. You solicit a murder of a specific victim, and you do it by persuading a specific person or persons to commit the crime. Incitement to murder is to call on the general public to commit that crime. It could be incitement to murder a specific individual; for example, a public statement telling residents “If Mr. Jones comes anywhere near our neighborhood, he should not get out of here alive.” Or it could be calling on the public to murder a class of people: “Let’s not allow migrant workers to enter our neighborhood and get out of here alive.” That is incitement.

In Israeli law, there are several categories of incitement that have been criminalized. One category of incitement, which is also a criminal offense under international law, is incitement to genocide. Incitement to war crimes or incitement to crimes against humanity do not constitute criminal offenses. Incitement to genocide—public incitement to genocide—is a crime in and of itself regardless of whether the genocide is actually carried out. And this principle is anchored in the 1948 UN genocide convention, and also in the 1998 Rome Statute that established the International Criminal Court, which includes an article specifying that incitement to genocide is a crime.

Israel signed and ratified the UN genocide convention in 1949, which defines and criminalizes the crime of genocide and imposes on the international community the obligation to prevent such acts and punish those responsible for them. Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben Gurion, allowed it to be signed, and, in fact, this is the only international treaty that Israel has signed and ratified that grants international tribunal jurisdiction over conflicts vis-à-vis the implementation of the convention. Every other international convention to which Israel has been a signatory has since been signed with a reservation clause that limits jurisdiction over Israeli matters and denies international tribunals the power to adjudicate Israel’s actions. And we can understand why this exception has been made. First of all, in 1949, international law in general seemed a much better friend to Israel than it does today. International law actually allowed Israel to be established, or at least helped facilitate its establishment. And second, the Jewish people were the generic and obvious victims of genocide. No one thought that one day genocide would be alleged against the Jewish state itself.

The exceptional status of Israel’s membership in the genocide convention explains why South Africa could initiate proceedings against it in the International Court of Justice (ICJ), when under no other circumstances could a so-called contentious, as opposed to advisory, case against Israel be opened there. The difference between the two is that an advisory opinion case asks the court for a legal opinion that, while authoritative, is not binding, whereas a contentious case asks the court to adjudicate a conflict and render a judgment that is binding. This unique character is also why the General Assembly can only refer cases—for example, the legality of the Separation Wall (2004), the legality of the occupation (2024), the Israeli obligations regarding humanitarian and UN agencies in the Occupied Palestinian Territories (2025)—to the ICJ for an advisory opinion. The tools of advisory opinions do not need state consent, but let’s leave that aside for now. Having signed and ratified the genocide convention, Israel then incurred the obligation to adopt the norms of this convention into domestic law. Thus, in 1950, Israel also enacted legislation through the Knesset that effectively enshrined the norms of the genocide convention in Israeli law. Consequently, genocide is considered a crime under Israeli law. And under the definition of that crime, there are also all kinds of derivative offenses, so that, ultimately, not just the commission of genocide but also the attempt to commit genocide is a crime. Aiding and abetting genocide is a crime. And inciting genocide is a crime. And, by the way, in Israeli law, all of these transgressions carry the maximum penalty of death.

One interesting aside: Israel has also enacted a specific law to deal with crimes by the Nazis. And in that distinct law, the law for the punishment of Nazis and those who aided Nazis is precisely the law under which Israel brought Eichmann and others to justice. In that law, as it happens, the definition of genocide is wider than the definition given in the genocide convention.

The term “genocide” was coined and defined by Raphael Lemkin, a Polish-Jewish jurist from Lvov. I would strongly recommend the excellent book East West Street by Philippe Sands, which tells the story of, among others, Lemkin and his struggle to get the crime of genocide enshrined into international law. Lemkin had a vision of genocide that entailed the destruction of a group by a variety of means, not just by killing members of the group. For him, genocide was a concerted effort by a state with all of its powers and tools to destroy a national, ethnic, or religious group. Killing is one major tool, but so is crushing their political institutions, destroying their economic means of production, erasing their educational system, eliminating their leadership, and annihilating their cultural properties. All of those may be acts of genocide. For Lemkin, genocide was the act of narrowing down humanity’s group diversity, destroying a group of people and the way of life that population embodies.

In 1945, Lemkin lost the battle of getting the crime of genocide formally recognized at the Nuremberg trials; the framework for the trials established at the London Conference of August 1945 did not encompass genocide, only crimes against humanity. When it came to the mass murder of Jews, the Nazis were convicted of extermination as a crime against humanity, but not of genocide. Later on, however, Lemkin, who had fled to the United States during the war, managed to convince the United Nations to establish the genocide convention. But the definition of genocide adopted in the convention was much narrower than that which Lemkin had originally envisioned. It included only two forms of destruction: physical, namely killing directly or causing death, and biological, namely preventing the next generation by means of forced sterilization, but it did not include cultural or spiritual destruction. When I give lectures to students, I ask them: “If we compelled all Jews to convert, so that there wasn’t a single Jew left on the planet, would that constitute genocide?” No, that would not be genocide under the genocide convention. But under Lemkin’s definition, it might be.

There are many explanations as to why the international community adopted a much narrower vision of genocide. One was certainly the concern of the colonialist powers that under the broad definition of genocide, any type of colonialism might come to be considered a genocidal project. The genocide convention ultimately defined genocide as either the physical or biological destruction of a group done with an intention to destroy that group. So, if you kill many members of a group, or create conditions that make life impossible for the group, that is not in itself sufficient to make you responsible for genocide. You have to enact this mass killing with an intention to annihilate the group. International courts subsequently made rulings and interpretations that narrowed the category even more, and what can serve as proof of intention has been interpreted very narrowly by them. Unless the perpetrators openly declare that their intention is to commit genocide, inferring intention from deeds can only be accomplished if that is the only reasonable conclusion to be drawn from those particular deeds. Not the most reasonable, but the only reasonable conclusion. By the way, this interpretation is currently under review in two important cases pending at the ICJ—a case that deals with the allegation of genocide in Myanmar, and the South African case against Israel.

Let’s take an example from Gaza. Israel has starved the people of Gaza. It has blocked humanitarian aid, and blocked food from entering Gaza. It has bombed the pipes that provide water. It has bombed the facilities that clean the water. It has created a humanitarian catastrophe and spread famine. One reasonable explanation for this set of actions would be that Israel wants to destroy the people of Gaza, and that is genocide. Another reasonable explanation, however, might be that Israel wanted to put pressure on Hamas so that it would surrender and release the hostages. Now, let’s assume that the genocidal explanation is more reasonable; according to international case law, that’s not enough. Because as long as there is another reasonable explanation, we cannot assume from the deeds that there is the requisite intention.

We have digressed, but for all these reasons, incitement to genocide is easier to prove than genocide itself. You don’t need genocide to actually take place in order to find someone responsible for its incitement.

Does the charge of incitement to genocide still need to establish the intent to do so?

Yes, but it’s easier to do this because, first of all, there is a presumption in every legal system that people intend what they say, and that they intend what is reasonably understood from their words. So, when someone says, “Why do we have the atom bomb if we’re not using it in Gaza?” the burden shifts to that person to prove he didn’t mean that we should nuke Gaza. If, in the context of a discussion about who is and who is not a legitimate target of attack, someone says, “Well, only those who are directly responsible for October 7 should be killed, we should not target innocent people,” and someone else says, “There are no innocent people in Gaza,” then the reasonable inference to be drawn from the latter person’s statement is that everyone in Gaza is a legitimate target. When you livestream a constantly updating ticker on your website of how many terrorists Israel has killed in Gaza so far, and that number matches exactly the number reported by Gaza’s Ministry of Health of the total number of people killed, including babies, that means you are saying that all those individuals are terrorists. And when you say that all of them are terrorists, you mean that they should be eliminated. I’m giving only a few examples, but there are hundreds more like this.

If incitement to genocide already constitutes such a serious crime in Israeli law, what was the rationale for additionally including incitement to violence and incitement to racism? The latter was especially surprising given how ethnonationalism, and therefore racism, are written into Israeli law. What does it mean to single out Channel 14 for incitement to racism?

Putting aside for a moment the statements that, in our view, clearly qualify as incitement to genocide, there were many of other statements that, while not incitement to genocide, still involved incitement to violate the internationally recognized laws of war. Incitement to use starvation and to bomb residential areas constitute incitements to commit war crimes, but this is not an offense under Israeli law—nor, for that matter, is it a crime under international law. Given these circumstances, we found that the most effective legal strategy was to allege other types of relevant incitement that are criminalized under Israeli law.

So, Channel 14 is vociferously encouraging the use of a kind of force against Palestinians in Gaza that is illegal for soldiers to use under international law, and therefore this meets the criteria of incitement to violence. Unlike incitement to genocide, incitement to violence has to occur in circumstances that a judge would be convinced has the potential to be translated into action. So, there’s an element of statistical probability at work in this particular charge. If someone who is effectively a nobody makes a comment on social media that could be considered incitement to violence, there’s probably no case there because there’s such a low likelihood of the statement having any effect. But if a political or religious leader, someone who has significant numbers of followers, makes an analogous statement calling on his followers to use violence unlawfully, that would be a crime.

And is it the case that the national context in which a statement is made can help determine the extent of incitement?

Yes. The context is not only about the identity of the person making the inflammatory remark, but also about the timing of the statement. There are moments when the air is filled with gasoline, and a small spark can blow everything up. After October 7th, Israelis were understandably enraged. So, in that wartime context, incitement becomes lethal—more so than in calm days.

If we have understood you correctly, another aspect of context would come into play around the issue of an aggregate editorial line. In that framework, context is constantly being reinforced and magnified by an entire series of statements—by a series of personnel, personalities, et cetera.

Yes, it’s critical that this incitement is an ongoing phenomenon. It’s not a one-off. If you are a viewer of Channel 14, you get that line every day. Repetition normalizes the idea, for example, that there are no innocent people in Gaza. That specific point has, in fact, been a recurring theme in Channel 14’s broadcasts since the beginning of the war.

If you heard it once or twice, you could think, “Well, they’re very furious, so it’s like cursing someone.” But when you have that sentiment drummed into you constantly over many months, it gradually normalizes the idea. When people routinely talk about bombing residential neighborhoods to dust, then we get accustomed to the notion that this is something legitimate.

You also raised the issue of incitement to racism. I understand where you’re coming from when you say that the Israeli system of governance is one big racist endeavor, but that’s not how Israel sees itself. That’s why we have a law that criminalizes incitement to racism, because we are not, in our own eyes, simply a Jewish state. We’re a democratic Jewish state, and whether you like it or not, this self-image is extremely powerful.

Now, I should add that this self-image has become less and less persuasive even internally. When I was growing up in the 1970s and 1980s, that idea of a democratic Jewish state was the governing ethos: Yes, Israel is the homeland of the Jewish people, but it’s also a pluralistic, democratic country where other groups, namely non-Jewish citizens, mainly Palestinians with Israeli citizenship, should receive equal individual rights. It was clear that it is a state that does not have a racist ideology. (For the sake of clarity, I should mention that Palestinians in the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Gaza strip are not citizens of the State of Israel; they are under Israeli occupation and are stripped of their civil and political rights. It is in Israel proper that there are two million Palestinians who are citizens of Israel and form 20 percent of its population). It took me many years to see through that facade.

There are Palestinian members of the Knesset, and there have been Palestinian ministers in the government, and we currently have a Supreme Court judge who is Palestinian. We have all these alibis, and it took me many years to realize that these are actually very weak alibis. Because at the same time as you have these supposedly exemplary embodiments of egalitarianism, there were so many policies and practices in place to dilute and almost completely empty ordinary Palestinian-Israeli citizenship of value. But this depletion is achieved in a very complex way. It is not written into law. If you look at the law—except for a small number of important laws that are obviously discriminatory, such as the law of return—in general, they are to be applied to all equally. You need to understand the details of how the Israeli state works in order to understand how the law can exist and be respected without actually securing equality for the day-to-day existence of Palestinians. My good friend the political geographer Oren Yiftachel has developed the concept of “ethnocracy,” which is exactly what we have in Israel. It’s where you have a seemingly democratic governance system, but underneath a very thin crust, you have policies and practices that make sure that all centers of power remain under the control of a certain ethnic group. And, concurrently, that the other ethnic groups will always be inferior.

Since it’s not written into the law, however, and all Israeli citizens, including the 20 percent who are Palestinian, have the right both to vote and to be elected, the enforcement of bias is more subtle. The image of being a vibrant democracy is important to the state’s functioning, on both the domestic and the international level. The need to preserve the image—however specious or shallow it might be—then becomes a powerful tool for me to instrumentalize as a human rights lawyer. The Israeli state has to pay in cash, as it were, to maintain that image. And this “cash” has enabled some of my biggest victories in court. These successes won’t actually undermine the system; they won’t change the basic tenets of its operation. But from time to time, you have to pay royalties on the conceit of being a fair democracy in order to maintain that pretense.

What you’re saying now brings to mind remarks that you made in an interview from 2018 about a case of yours in Bil’in in the Occupied Territories. There, you discussed the complex relationship between victory and success in a scenario where you can prevail in individual cases, such as the one in Bil’in, but can’t challenge the overall structural inequity. You spoke then of how difficult it can be in this context to maintain a clear line between success and failure.

It’s worse than that. It’s not just a victory or success; it’s whether I become, despite all my good intentions, a collaborator with the existing system by virtue of giving it a chance to show that it can work on behalf of Palestinian rights. By enabling the Israeli state to occasionally grant victories to me and my legal arguments, I allow it to maintain its democratic self-image, which is, in fact, a false image. So yes, that’s the existential dilemma that I think human rights lawyers in Israel face when going to court; maneuvering on this thin crust that I mentioned, we embolden the argument that Israel is a democracy.

Has your thinking on this issue changed over the past seven years since that interview, as the situation has become even more dire?

Well, around the time of that interview, I wrote a book called The Wall and the Gate: Israel, Palestine, and the Legal Battle for Human Rights. That book was a very long study of precisely this dilemma. The question of what human rights activists, and specifically legal activists, should do in the face of a regime that—while operating in systematic violation of democratic principles—allows them certain internal paths of litigation. This is a massive question that began to be confronted by lawyers long before my time. Even during the Vietnam War, lawyers in America were asking themselves, “Should we go to the American courts to challenge American warfare policies?” And similarly, lawyers in South Africa thought, “It’s true that we can get success here and there for specific black clients, but should we go to the courts of the apartheid regime? Are we not legitimizing the system by even applying for justice there?” I’ve been grappling with the issue for a long time since it concerns the validity of my entire vocation.

How do you think about these dilemmas with respect to the very case you now have before the High Court of Justice?

First of all, I came to the conclusion that, for me, the possibility of neglecting, or boycotting, the courts is never an option so long as there are clients who want to apply to them, especially if the clients come from the disenfranchised or victimized community. I’m not the one to decide for Palestinians whether they want to turn to Israeli courts for the small chance that they will get remedy. They do get remedy from time to time. I do periodically win cases, especially ones that have a specific effect and no wider ramifications. So, if someone finds his or her own particular olive grove in danger of being uprooted by the government, I can take their case to court and perhaps win. In the book, I described an imaginary discussion between a lawyer and a client. The lawyer takes the position, “We shouldn’t go to court,” and tries to explain to the client why that is, even though there’s a chance that she would indeed get a remedy from that court. This would never happen with me because if a Palestinian asks for my help, I will help. But even so, there can be larger issues of strategizing that must be factored into my decision, and sometimes there are cases that should not be pursued because the harm that would come out of them would be greater than any potential good.

This current incitement case is, I think, a strategically correct case. Whatever happens, it stands to challenge the larger system and the facade of democratic equality. It’s an important case in that it will present valuable material on the relationship between what’s going on in international law and in Israeli domestic law. I also think that this case confronts the Israeli judicial system with a fundamental question about our identity. Who are we? Are we still what we thought, what we were told at school? We were taught that we are the descendants of Holocaust victims who realized that there are things that are simply not done. We were educated to believe that we created a state that is a haven for Jews, but also a democracy. Are we in fact now a state in which racist and genocidal incitement are permissible? In that sense, it’s a very powerful case.

On the face of it, your case seems overwhelmingly strong. What do you envision as being a conceivable defense? And how do you see it enduring, beyond what the respondents do, in the Israeli psyche or discourse?

I have answers, but I obviously can’t suggest a defense for a case that I’m litigating right now, one in which the defense of the attorney general has not yet even been heard. Channel 14 did submit a response, denying incitement to genocide, and alleging that the petitioners are trying to silence it for political reasons. From my own perspective as a lawyer, I think Channel 14’s extensive track record of broadcasting incitement is simply incontestable. I don’t think it is possible to defend this case. That said, there is an issue of prosecutorial discretion that could be invoked here. Prosecutorial discretion means that even if prosecutors say that a given case raises considerable suspicion, or even certainty, that a crime has been committed, they can still decide not to pursue the case for all sorts of reasons. I don’t want to imply that this is what I think is likely to happen here. I think that invoking prosecutorial discretion in this case would be preposterous. Prosecutorial discretion is usually drawn upon in very insignificant cases, where the offense is a misdemeanor, or there are some alleviating circumstances. Here, it is the exact opposite of that. We’re dealing with one of the worst offenses that we can imagine, and the offense has, moreover, been committed by a roster of some of the most powerful people, politically and publicly.

On top of this, the offense is foundational to the identity of the Israeli state.

Exactly. I think that most people in the attorney general’s office would consider this something that needs to be investigated and prosecuted, but politics makes it very, very dangerous for them to actually do so because this is an extremely powerful channel deeply connected to the prime minister and to the governing coalition.

Furthermore, the attorney general’s office is already engaged in many battles with the current government. Were the attorney general to push back against the petition instead of accepting our demand to launch an investigation, this decision would not be based on legal reasons. They would have to word it in legal terms, of course, but, in reality, the reasons would be political.

We wanted to ask you about the role of the courts in the current Israeli political landscape more generally. You’ve discussed elsewhere how at some point the political opposition to the government became so weak, almost non-existent, that litigation and the work done by NGOs became the primary, or even only, mode of opposing key government policies. Could you talk about how you envision that redefined mandate shaping events in the future? It would also be great to hear how the government’s judicial overhaul impacts the void that you’re filling.

The issues you’re raising are ones I commented on before the judicial overhaul. To be precise, what I meant then was that there is no parliamentary opposition to Israeli policy toward the Palestinians. In the past, there had been two parliamentary camps. One aspired for annexation, and the creation of a single apartheid state between the river and the sea—without providing, of course, civil rights to Palestinians. The other camp was pursuing partition and a two-state solution.

That second camp collapsed politically—it simply evaporated, for all kinds of reasons. And so, the only institutions that were left to push back against the expansionist practices designed to violate Palestinian rights—policies that grab more land and push Palestinians into their urban enclaves—were human rights organizations, lawyers, and civil society in general. These latter groups are not programmed to be a political opposition. They are programmed to do the work that human rights groups do—that is, to represent clients and to educate the public on issues of human rights—rather than to become electable.

In this situation, it became the case that whenever the government was declaring a new policy or enforcing a new measure in the West Bank, journalists who wanted to quote the other side would come to us to fill the void; this was because the political parties that represent primarily the constituency of Palestinians with Israeli citizenship have been so delegitimized that the Israeli media usually ignores them in reporting public political disagreements. But we’re not the other side of the government. It’s true that we are the other side in the sense that we are the checks and balances on the government, but we’re not competitors to the current coalition. There should be a healthy opposition that plays that part, and such an opposition just doesn’t exist in Israel. That placed us in a very awkward position. Since we don’t have parliamentary tools, and we don’t have the tools that politicians have for influencing the public, one of the main tools left to us is litigation. It shouldn’t have been like that, but it’s what happened.

I must add that in some aspects it’s no longer like that. First of all because the Israeli political map has changed completely, and today there is a large opposition to the values the government is promoting. The opposition did not emerge on the issue of settlements, nor on the issue of the treatment of Palestinians, but nonetheless, there is strong opposition to the current government for other reasons—because of the judicial overhaul, because of Netanyahu and his corruption, but also in relation to the radical right. There’s an opposition to their vision of Israel, and the huge demonstrations against the government, where hundreds of thousands of Israelis went out onto the streets, showed it. While this is not an opposition to the Israeli policy towards Palestinians, criticizing the government on its radical nationalistic and anti-democratic ideology opens the door to a discussion about racism and to opposing Jewish supremacy.

But the bigger reason why litigation has lost its primacy as a tool with which civil society can oppose the government is because the Israeli political right, which has been more or less in power for the last thirty years, has completely changed the character of the Israeli judiciary. For one, there was a generational change at the Supreme Court that led to the appointment of many new justices. These new justices were not of the type that still maintained the image of the 1980s that I talked about; many of them were rather blunt nationalists with conservative worldviews. For the first time, some of the justices were even settlers. That’s one reason the character of the judiciary has changed. The second is the judicial overhaul. The court and the judiciary have come under fierce attacks by the government, which tried, and is still trying, to weaken it, and the first victims were Palestinians, not Israelis.

The court has found itself under the magnifying glass, with every ruling it issues becoming a trigger for the government to agitate against it. The court has therefore had to choose very carefully the cases on which it expends its limited capital. Providing remedy for Palestinians under occupation, who have zero weight in Israeli politics, was always a very rare occurrence, but now the risk of providing tailwind to the lie that the right wing has been spreading about the court being a “leftist,” or even “pro-Palestinian,” institution has made it even rarer. A further disincentive to intervention by the court is the fact that the treatment of Palestinians was never at issue for the Israeli camp that views itself as “liberal” and that organized the massive demonstrations to protect the judiciary. Any pretense to engagement with the Palestinian cause was, of course, further dispelled after October 7th.

For a judge to protect a Palestinian today is almost a philanthropic enterprise. You don’t get anything in return, only trouble. If you do so, it’s because it’s the right thing to do. In the current environment, every victory for a Palestinian petitioner is immediately spun by the Israeli right to fuel a new cycle of incitement against the judiciary for being pro-Palestinian, for being a leftist, progressive, activist court. This is among the most colossal lies in Israeli politics; the court’s record from the last six decades—which I analyzed in The Wall and the Gate—proves how the court was essential in “koshering” almost every policy that violated Palestinian rights and allowed the establishment and expansion of settlements. Nevertheless, the lie works, and as a result, I think even those judges who would like to be more active in protecting Palestinian rights are intimidated by those advocating for radical judicial overhaul.

So, there are two issues here. One is the change in the composition and the character of the judges, and the second is the judicial overhaul that cows even those judges who are sympathetic to the kind of petitions we have put forward against Channel 14.

Are you suggesting that in order to assert the integrity of the court system, the Palestinians had to be entirely abandoned as a subject of concern for the judiciary?

Yes, the fractional percentage of petitions on behalf of Palestinians and their basic legal rights that used to be upheld was sacrificed after the judicial overhaul, and all the more so after October 7th. In the first weeks and months after October 7th, there were petitions submitted on behalf of Palestinian fathers, mothers, and families who had lost contact with their loved ones. Perhaps these individuals were being detained by the military; maybe they had been taken to Israel. No one knows where they are. No one knows whether they were injured. No one knows if they’re charged with anything. And the courts simply dismissed these petitions out of hand, without any deliberation whatsoever. I’ve made a career out of criticizing the courts—even in the 1980s and 1990s when they were functioning more robustly than today. But even so, I can say that ten or fifteen years ago, one wouldn’t find a judge who would completely seal their ears to the plight of a mother who wants to know, just to know, where her son is.

Some legal scholars have tried to understand what role, if any, international law retains at a time when its entire legitimacy seems to have been eroded. What do you think of this in the context of the specific challenge you face in Israel today? As the old political and legal norms crumble, how has the role of a lawyer like yourself changed and do you find yourself having to draw on new kinds of tools or to adopt a more provisional position in relationship to what might have once been counted on?

We Israeli human rights lawyers have been struggling with these issues long before the corrosion of the international rules-based postwar order began. Our experience here has long been of institutions that shift between distorting international law and adopting interpretations that go well beyond the legal consensus, or outright ignore it.

This is a phenomenon we’ve experienced, and that I’ve personally witnessed from the beginning of my career about three decades ago. To invoke a metaphor, what has changed for me—and it is a massive change—is that while the international legal framework might have altered in my courtroom because those who called the shots had begun distorting or ignoring the rules, I knew that around me, in the other parts of the house, the core tenets of international law as I understood them were, more or less, still being upheld. When I heard something completely outrageous, I could shout, “You’re acting in a way that no one outside this room accepts!” This is, to some degree, no longer the case. The distorting and ignoring of the fundamental principles of international law have now spread to other parts of the house. There is an episode of The X-Files in which someone wakes up one morning and suddenly discovers that he speaks a different language from everyone else. They all use the same words, but without the same meaning or grammar. Similarly, I suddenly find that I’m in a new reality where the president of the United States can say something that seems on the face of it nonsensical or criminal or both, but the world immediately starts aligning to accommodate that idea. When the US president says that the people of Gaza should be relocated somewhere else, it’s like saying that gravity is no longer the force that governs the relationship between objects. And, of course, the Netanyahu government says this kind of thing all the time.

Or consider Annalena Baerbock, now president of the UN General Assembly, who asserted, when she was Germany’s foreign minister, that civilians lose all protected status under certain conditions.

For example, yes. Look, there were cases in the past that undermined our sense of norms; I’m thinking of Abu Ghraib, Guantánamo Bay, and the extraordinary renditions. There were notable, egregious cases, but they were seen as aberrations. Not by everyone, but by most commentators. This was still the case, for example, when the first Trump administration officially recognized the annexation of the Golan Heights.

But what we’re seeing now is something completely different. And it’s too early for me to say how my colleagues and I can adjust ourselves to this shift. I’m still in a position where I cling to my network of international lawyers and international statesmen and stateswomen who believe that the UN charter and the international laws governing human rights and international humanitarian law are—I wouldn’t say sacred, because I’m an atheist—but the closest to what the sacred can be for a secular person.

These are insights and principles that we as a species have slowly, painstakingly evolved at the conclusion of thousands of years of civilization and mainly of atrocities—of suffering. We’ve reached these understandings with blood. We’ve created this system, which though not perfect is nonetheless optimistic and humanistic. And to crush this remarkable, shared guiding ethos now—well, I don’t know how we could overcome such a loss.

I must add that I believe that it will not be crushed. I genuinely believe that what we are witnessing is the most dangerous attack on international law and order since World War II. In fact, it’s arguably the most dangerous attack of all because it comes from the very actors who were supposed to guard it, who were supposed to raise it as their banner—even if they occasionally violated it. I’m not talking about merits, but only perceptions here. The United States has frequently violated international law. That’s important to acknowledge, but it’s also important that international law was a flag that America held aloft and rallied around.

Without question, this has also been the case with regard to Germany, probably the single most important guardian of the postwar international legal order. So, when the chancellor invites Netanyahu, a person who has international arrest warrants issued against him by the ICC for crimes against humanity and war crimes, to Berlin, or visits him in Israel and poses for a picture with him, that teaches the world that the previous standards no longer apply. That creates new norms. But, as I said, I believe this will pass. Because there’s nothing that can replace it. It’s not like the Cold War, where you had competing ideologies. You don’t have that anymore.

Do you think this petition has in itself come to be perceived as a threat to the powers-that-be at Channel 14 in ways that have led them to mitigate their incitement?

There are changes, but I’m not sure it’s because of the petition. There are also changes on the ground. A ceasefire was announced, which has not stopped the violence and killing but did lower considerably the intensity of fighting. Things are not the same in the war. After the petition was filed, they, of course, began devoting airtime to attacking us. Suddenly, they have an investigative piece on Zulat, one of the NGOs we’re representing, and against me personally. All of it is complete rubbish. So, the petition was clearly enough of a concern for them to feel they had to fight back. I’m sure that if the attorney general does eventually launch an investigation, we’ll see the channel engaging with it more seriously.

In this context, there’s another thing that we did not touch on, and that is advertisers. In my opinion, one of the main ways that audiences become psychologically habituated to the messages of incitement broadcast on Channel 14 is through the very ordinary, reassuring advertising that you watch on the channel. Between a segment containing incitement to genocide and incitement to a war crime, you might see an IKEA, Nestlé, or Carrefour advertisement or a car commercial.

We saw that someone has in fact made an online database of all the advertisers on Channel 14.

That’s right. And I think that at a certain point, the international interest in the petition will potentially raise red flags for advertisers. In Sweden, there have already been discussions around the issue of IKEA advertising on the channel. There’s more and more of that kind of thing happening. And that pressure could have an effect.

And perhaps the complex issue of humor is also relevant here. We were surprised and pleased to see that the question of tone is brought up in the petition as an important part of the legal case. How much harder is that to adjudicate? You can hold people accountable for their words, but tone is presumably a more subjective or elusive matter. Humor can inform the tone of remarks and, in theory, could mitigate or even defuse their express genocidal intent. Even in translation, we can see that there are attempts by the channel to deploy humor in a very particular way. It’s another form of normalization and of “giving permission” to the population. The conventions of civilized discourse sometimes turn out to have a role in preserving social integrity. When these are stripped away, the culture actually does degenerate, and this can translate into a real switch in how policy gets conducted. With Trump, there is a sense that he is a sort of emperor with no clothes who revels in his nakedness, and tells everyone else to revel in that shamelessness also. By treating the prospect of atrocities more with a kind of mild frisson of amusement than as a sinister threat, you can preserve a kind of strategic ambiguity without ever actually softening, let alone withdrawing, the threat itself. We see this in American politics all the time now. Trump is very funny sometimes, especially when he is being most cruel.

On Channel 14, it’s mostly cynicism, but there’s also humor, regular humor. The project that is being implemented by Channel 14 and by its equivalents in the US mediascape—as well perhaps in Europe—is one of legitimizing our hatred and violent aggression. And this is why it’s so appealing; we all have dark passions, we all have dark urges. The entire socialization project is based on how we suppress those dark impulses. And here come people who are good-looking, who are successful, who are funny, and who are very charismatic, and they tell you, “What are you afraid of? Just say it. You want to kill them? What’s the big deal? Just say it.” And suddenly, I let that sentiment out, and I feel so much better about myself. And in between this cathartic brutality, I see an advertisement for diapers or whatever. So, it’s no big deal. “Those old elites, those privileged people, taught you all this time that you were bad for having such impulses, that you were inferior. No! The opposite. You’re good.” That’s fascism—the essence of fascism. That’s what they do, and they do it very well. Humor is about lightness, the lightness of cruelty. It’s not, “Alright, let’s go into a dark space alone, and once we’re there, I’ll say in a heavy tone, ‘We have to kill them.’” No, I don’t want to be part of that; that’s too much. But this stays chatty and amusing. It says, “Don’t be afraid; join us.”

In parallel to humor, you also have the phenomenon of a live audience in the studio that claps and reinforces the messaging. It’s so powerful and smart. It’s not only this TV personality saying things you only whispered to yourself; there’s a whole crowd of regular people out there clapping hands and cheering, so you can feel, I’m not alone in this.

“I’m not alone in this.” That’s a very eloquent way of putting it, the sense of “I’m not alone in my worst self.”

Yes. Exactly.

It’s now late January 2026, six months after we conducted the bulk of our interview. We are about to publish this discussion, and wonder if you could provide an update on where things stand today, some sixteen months after you first initiated proceedings against the channel?

The attorney general has asked that the petition be dismissed on the grounds that she has not yet decided on whether to launch an investigation, that the decision-making process is underway, and hence that the petition is “premature.” This is a strange position to take, to put it mildly, given that this issue has been on the attorney general’s desk for more than a year.

Earlier this month, the attorney general and the police notified the High Court that it would take them eight more months to render a decision on whether to launch a criminal investigation. They explained their amazingly slow timeline by the fact that we, the petitioners, had provided them with so many examples of allegedly inciting statements made on the channel’s programs that it would take a long time to review them all.

This is, of course, a poor excuse for a system that is lightning fast when it comes to review alleged incitement by Palestinians. In fact, in their notice to the court, they conceded that the unit responsible for identifying incitement will be busy in February and in March, because that is the period of Ramadan, and “past experience shows that during this period of the year, the opinion unit is required to engage in urgent examination of many statements that raise suspicion of offenses of incitement to violence, incitement to terrorism, and support for and identification with a terrorist organization.”

I’ve heard many excuses in my life for why authorities take forever to do something they don’t want to do, but this one is among the most outrageous: We don’t have time to decide whether to investigate Channel 14 because we already know we’ll be busy investigating Arabs. Because that’s what we do during Ramadan. And obviously that’s a thousand times more important than investigating suspicion of incitement to genocide by Jews.

Now the High Court will have to decide what to do with law enforcement authorities that are unwilling to investigate Jews for incitement to war crimes and are doing everything they can to avoid it.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14623528.2025.2558401

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01436597.2025.2462787

https://jls.tu.edu.iq/index.php/JLS/article/view/1034

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/17506352231178148

https://academic.oup.com/ccc/article/18/4/310/8246022

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13537121.2024.2394292

For additional reading from independent publications and platforms, see:

https://thebaffler.com/latest/lying-eyes-malekafzali

https://jewishcurrents.org/the-genocides-the-new-york-times-forgot

https://cfmm.org.uk/bbc-on-gaza-israel-one-story-double-standards

https://www.theguardian.com/media/2024/feb/04/cnn-staff-pro-israel-bias

https://www.commondreams.org/news/israeli-human-rights-groups-gaza-genocide

https://www.commondreams.org/news/israel-gaza-genocide-2673945281

https://thepalestineproject.medium.com/yes-it-is-genocide-634a07ea27d4

https://jacobin.com/2024/07/amos-goldberg-genocide-gaza-israel

https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/hrbodies/hrcouncil/sessions-regular/session60/advance-version/a-hrc-60-crp-3.pdf

https://www.middleeasteye.net/opinion/war-gaza-pro-israel-bias-western-media-off-scale

https://theintercept.com/2025/07/30/new-york-times-hamas-aid-israel-gaza-famine

https://zeteo.com/p/new-york-times-whitewashing-israel-genocide-gaza

https://deadline.com/2025/07/bbc-letter-israel-pr-charles-dance-miriam-margolyes-1236446798

https://www.dropsitenews.com/p/bbc-civil-war-gaza-israel-biased-coverage

https://theintercept.com/2025/08/04/gaza-famine-diabetes-illness-medication

https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2025/7/23/yes-the-new-york-times-is-committing-genocidal-journalism

https://theintercept.com/2024/04/15/nyt-israel-gaza-genocide-palestine-coverage

https://jacobin.com/2024/02/new-york-times-anti-palestinian-bias

https://theintercept.com/2024/02/07/israel-palestine-journalism-nyt-thomas-friedman

Michael Sfard, based in Tel Aviv, is one of Israel’s foremost human rights lawyers. His books include The Wall and the Gate: Israel, Palestine, and the Legal Battle for Human Rights (Metropolitan Books, 2018), and his articles on human rights law have been published in Haaretz, The New York Times, The Independent, and Foreign Policy. In 2012, he was the recipient of the Emil Grunzweig Human Rights Award.

Sina Najafi is editor-in-chief of Cabinet.

George Prochnik is the author of the memoir I Dream With Open Eyes (Counterpoint Press, 2022); Stranger in a Strange Land: Searching for Gershom Scholem and Jerusalem (Other Press, 2017), shortlisted for the 2018 Wingate Prize; and The Impossible Exile: Stefan Zweig at the End of the World (Other Press, 2014), winner of a 2014 National Jewish Book Award. He is an editor-at-large at Cabinet.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.