The Medicine Barrel

The gospel of Viavi hygiene

Paul Collins

The worst of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake came well after the shaking stopped, as fire swept the downtown district, fueled by leaking gas mains. Amidst the conflagration, there remains a curious account by a girl on Portola Street. Her father worked for real estate magnates Herbert and Hartland Law, and as the fires raged across the city for a second day, he was making runs to the family home, driving a horse-drawn wagon filled with barrels. Teams hastily dug ditches for the barrels and covered them over in the hope of saving their precious contents from the blaze.[1]

They probably hadn’t the faintest idea what those barrels contained.

• • •

The two brothers responsible for shaping San Francisco in the earthquake’s aftermath are now as buried in obscurity as the barrels their employees hid away. The Law brothers were born in the 1860s by the mills of Sheffield, England, but soon immigrated to Chicago, and in 1884 they struck out for San Francisco. By 1906, Hartland was established as an M.D., and Herbert as a chemist. More importantly, they headed local business associations and owned prominent San Francisco buildings, including the new Fairmont Hotel. Their holdings were worth millions.[2]

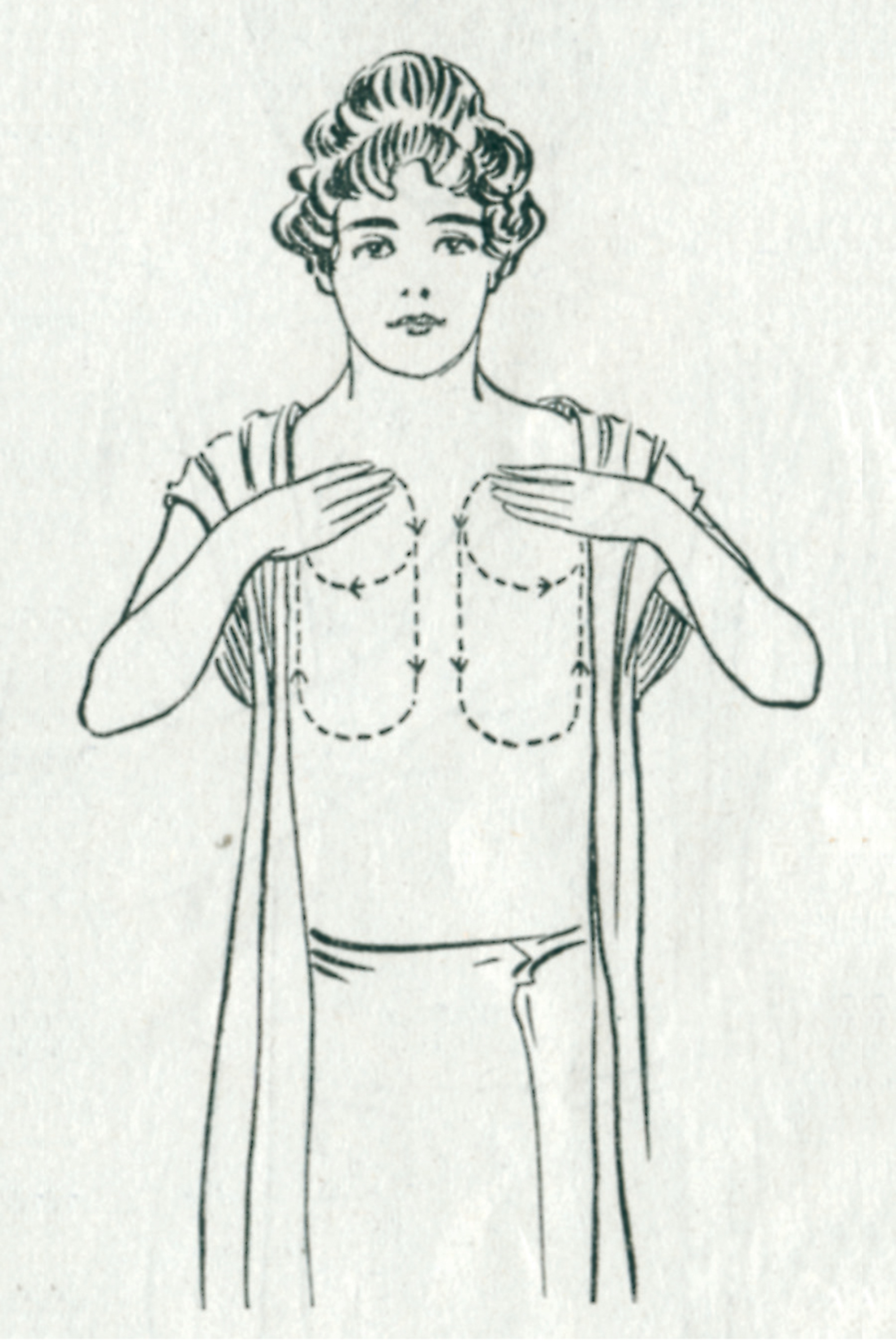

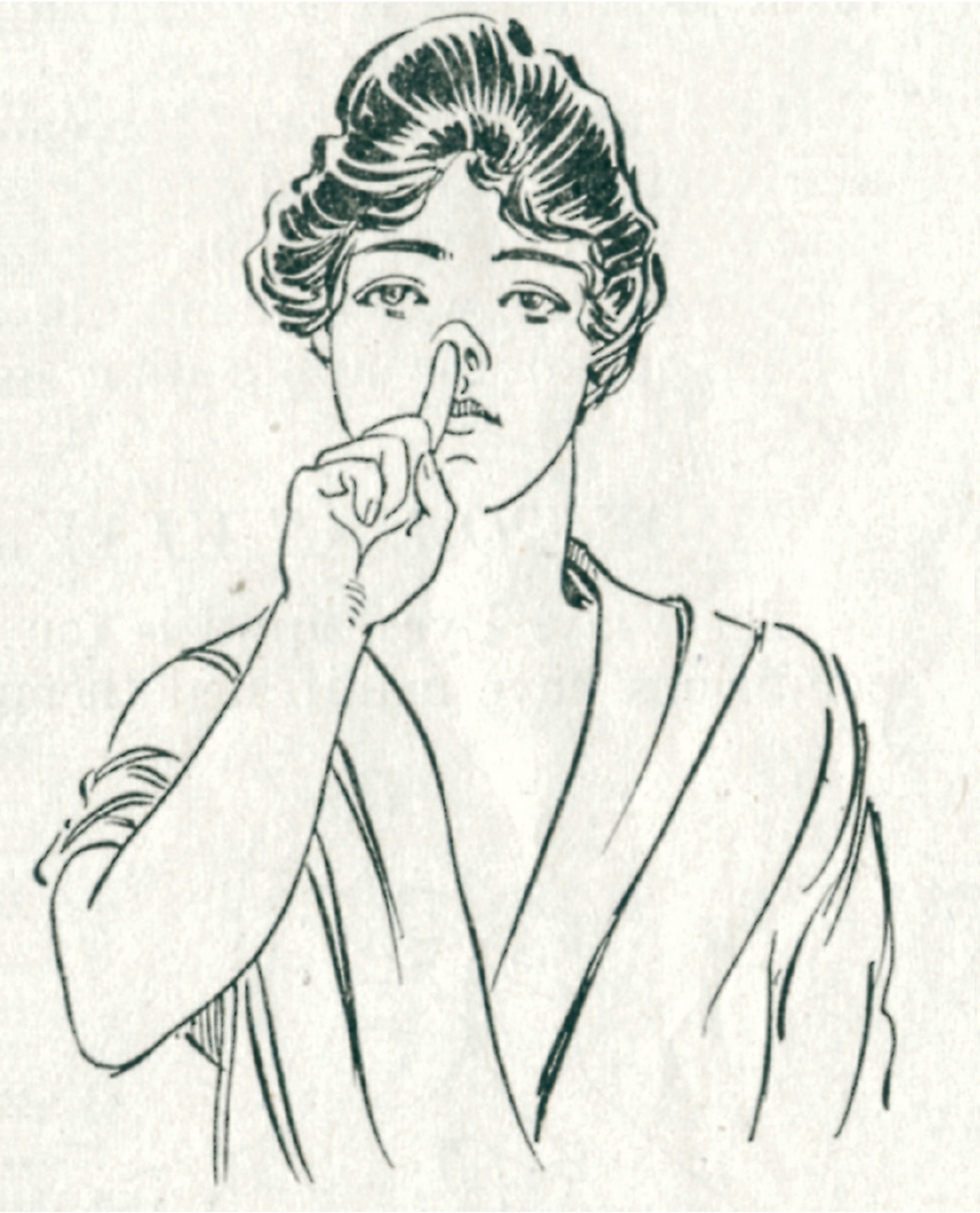

How did they do it? The secret was Viavi. In 1899, a volume of medical advice made its way into American and British homes: Viavi Hygiene, by Hartland and Herbert Law. The book ministered to myriad complaints: tumors, back pains, constipation—and, of course, the Victorian favorite, catarrh. Like many patent medicines, the Viavi system promised common sense and hard science—namely, through Viavi Capsules, Viavi Royal, Viavi Laxative, Viavi Cerate, Viavi Iron Tonic, and above all else, the Viavi douche.

Viavi Hygiene went through six editions in three decades, and the Viavi Company grew into a behemoth, at its height boasting 20,000 employees in ten countries, with offices in virtually every American city as well as in London, Paris, Edinburgh, Dublin, and Johannesburg. But Viavi was as notable for its invisibility as for its importance. While contemporary magazines teemed with advertisements for Cardui tonic, Kickapoo Indian Worm Killer, and Brewster’s Medicated Electricity, none were placed by Viavi. Instead, you find tasteful announcements like this, quietly tucked into the classified section of the New York Times on 21 June 1931:

WOMAN, ambitious, to qualify for position of interest explaining Viavi preparations; eventually to manage and organize territory; local and up-state opportunity open; excellent commissions; permanent position offered. T.L., 333 Times.Among such dreary jobs as selling “an absolutely new educational plan for children,” and door-to-dooring “Daintymaid, a sanitary necessity,” Viavi must have looked downright alluring. It certainly had a decade earlier, when the Times ran an advertisement lamenting how “the intelligent, mature woman, inexperienced in business, faces a problem in securing satisfactory vocation.” In the 1940s, the Times was still promising to “LADIES, a dignified, splendid opportunity.”

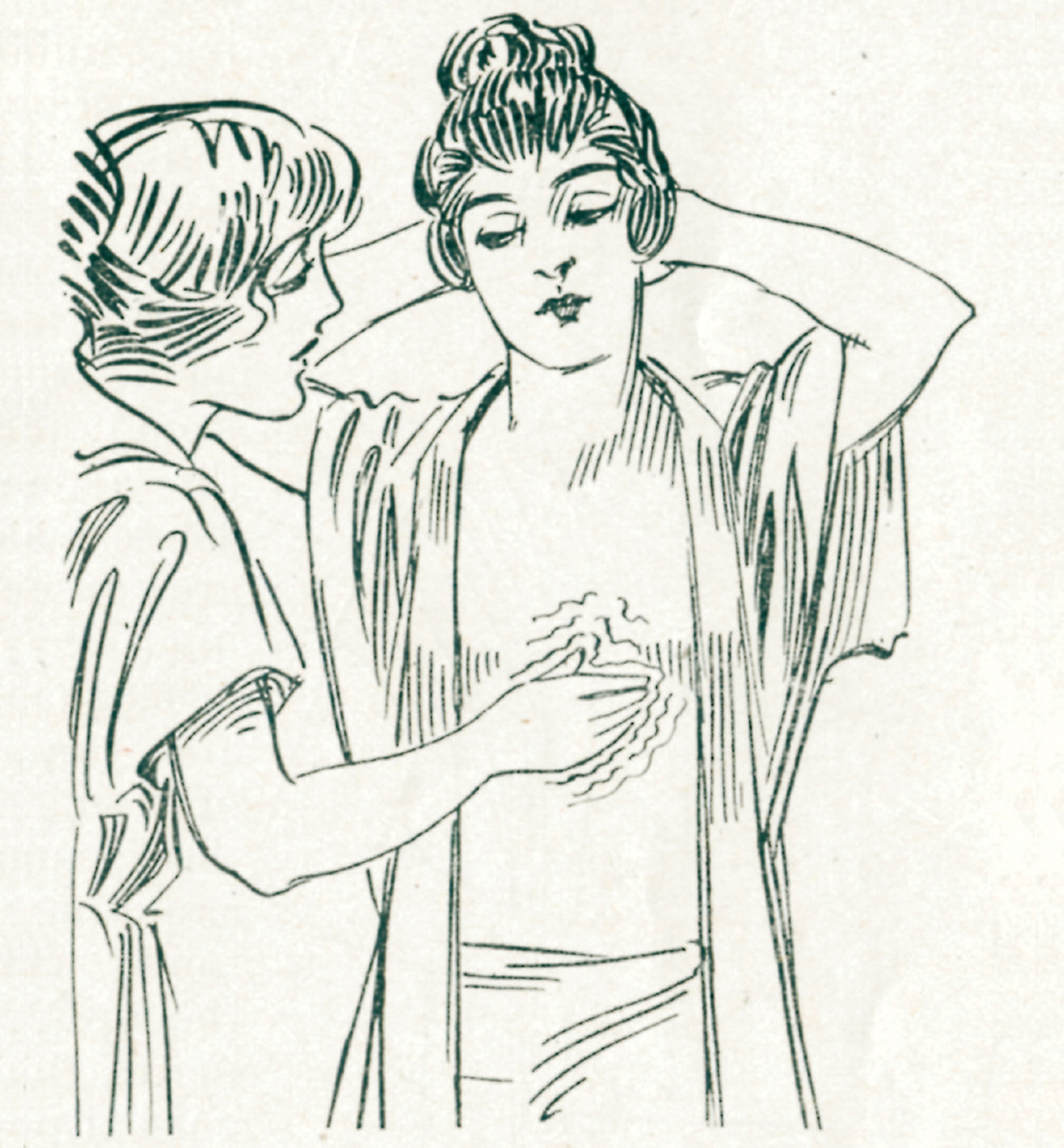

The Viavi gospel was then passed around by recruits to neighbors at lecture halls. The Viavi Manager’s Guide dictated everything from how to arrange the furniture in a Viavi office, to the proper wording of newspaper ads and lecture titles, to the best day and time to hold lectures (2 p.m. on Tuesdays). Viavi saleswomen were instructed to book Masonic halls, temperance unions, and churches, where they disguised sales pitches as “health lectures.” These invariably ended with virtually everyone in the audience being diagnosed as needing Viavi treatment.[3]

Viavi employment was carefully pitched to middle-aged women. “We do not want old, worn-out solicitors, peddlers, people devoid of ambition, and the like,” the Guide scolds. It advises managers to recruit nurses and dressmakers, as both were privy to gossip about the female ills Viavi remedied. But the best recruits came from a class that was trusted yet discontented:

TEACHERS.—There is probably no class of people better fitted to our work than school teachers. Fully eighty percent of them are dissatisfied with their occupation. The remuneration of skilled teachers is constantly decreasing; the number of people desiring these positions is constantly increasing. The necessity of the directors to get fresh, vigorous, young blood means that the older ones will be out of employment at a time of life when they most need permanency.Novices underwent two screening interviews, then five training lectures on the wonders of Viavi, the fabulous commissions, and careful rules on how to book lectures and arrange the Viavi office. Then recruits had to place a deposit for half the retail value of a traveling saleswoman’s kit containing hundreds of dollars worth of Viavi goods. Unlike any other form of employment—except, say, Amway—you faced wasting all that time and effort, and fabulous future commissions, unless you now paid to get in. As the Guide explained, “It is just as important to secure new workers as it is to sell the remedy.”[4] For Viavi wasn’t merely selling douches: It was selling douche employment.[5]

But what was in those barrels?

The question arose soon after Viavi Hygiene hit the shelves. In England, the 10 March 1900 issue of The Lancet reported on a coroner’s inquest for Mrs. Elizabeth Mary Lake, an East Sussex resident. She had died of a perforated ulcer at the age of 42. A married woman of Lake’s age was precisely the customer Viavi sought, and the coroner found a representative of the British Viavi Company, Miss O’Dowda, to have been Lake’s sole source of medical advice.

The Lancet describes the hapless Miss O’Dowda at the inquest:

Miss O’Dowda, examined by the coroner, is either in reality, or poses as, an ignorant woman. She said that she was the branch house manager for the British Viavi Company. Asked “What is the Viavi Company?” she said that she did not understand the question. Further pressed she said that it was a company for health treatment at home. Her business was to give instructions with regard to the remedies to people who wished to buy them, to advise them as to their application, and to put them in touch with the hygienic department in London, which was controlled by a medical adviser, where they are treated by correspondence from London…. The medicines were composed of vegetable substance, but she [Miss O’Dowda] did not know what they were.

Mrs. Lake’s diagnosis-by-mail had not been for an ulcer, but a “tumorous condition of the bowels,” for which Viavi products had been prescribed. The coroner then called upon the London diagnostician for Viavi:

Henry Thomas Woodward, describing himself as M.D. of the University of Pennsylvania, said that … his business was to look over the correspondence from patients and return answers. Asked by the coroner if he had any objection to telling the court the ingredients of the medicine, witness replied that he had no objection but did not know.

Nobody, it seemed, knew exactly who they working for or what they were selling.

On 17 January 1903, The Lancet had worse news for Viavi, reporting a court decision against Viavi “for breach of contract—i.e. for failing to cure,” and noting something curious: co-founder Hartland Law, M.D., was not listed in the Medical Register. Moreover, his brother Herbert Law, F.C.S., did not appear on rolls of the Fellows of the Chemical Society.

The Lancet does not seem to have dented Viavi’s business, and Viavi Hygiene went into a second edition. A lavish headquarters was built at the corner of Van Ness Avenue and Green Street, and the brothers acquired buildings along Mission and Montgomery Streets. But their most ambitious purchase was the luxurious Fairmont Hotel, which on 18 April 1906 was just two weeks from its grand opening.

The earthquake that struck that day represented spectacularly bad timing, for it occurred hours after the wrecked Fairmont’s insurance had expired. Though many of the fires were out by the morning of the 20th, Army officers began needlessly dynamiting other buildings to create firebreaks. The demolition expert was blind drunk, and the Viavi Building was destroyed with an enormous excess of explosives, spraying flaming debris across the city and setting off a new conflagration which roared over Russian Hill and through North Beach, completely destroying over 50 city blocks.[6]

But disaster only made the Laws stronger, as the city’s reconstruction consolidated their position as real estate magnates. In the three years that followed, the duo handled seven million dollars worth of property deals, pouring $1.84 million into rebuilding the Fairmont alone. Herbert co-founded the local Chamber of Commerce, became director of Wells Fargo Bank, and chaired the civic planning committee for new streets—including those in the Marina, a district built upon marshland that the Law brothers had drained and filled.

But not everyone was impressed with the Law brothers. Four months after the earthquake, Collier’s magazine began to publish muckraker Samuel Hopkins Adam’s exposé of patent medicine, a landmark series titled “The Great American Fraud.” Adams saved special vitriol for “a fake concern, called the Viavi Company, which preys upon impressionable women.” Even more damning was a lengthy article in the April 1907 California State Journal of Medicine, which commissioned a chemical analysis of Viavi Capsules to reveal once and for all what this miracle drug contained: golden seal extract and cocoa butter.

The Journal also uncovered a compelling reason for the popularity of certain Viavi products. Women knew the royal in Viavi Royal implied pennyroyal, though openly selling abortifacients was illegal. Viavi vehemently denied that its products were meant for any such purpose—but Viavi literature extolled the douche’s ability to “limit the number of offspring.” Herbert and Hartland were no feminists; they followed the money, and were happy to prescribe vegetable grease to women dying of diabetes and rectal cancer. Surely, the Journal thundered, the politicians gathering to commemorate the earthquake’s first anniversary at the resurrected Fairmont would realize that blood money had rebuilt the hotel. But, “Will they care how the money has been garnered?”[7]

Apparently not. The American Medical Association complained for decades about Viavi patients dying from lack of treatment, while the company continued to flourish. The Law brothers lived to ripe old ages and died as multimillionaires.[8]

• • •

So what happened to the Viavi Company? After the deaths of the Law brothers in 1948 and 1952, one might assume Viavi died a quiet death along with its founders. There is no website, and no trace of it in newspapers and magazines. But there is a phone number. It is for Viavi Brand Products, based in Lafayette, California. A friendly receptionist answers the phone; when asked if it’s a hundred-year old company, she ponders it for a moment.

“I don’t know … probably? Yeah. I think it’s been around a long time.”But surely this Viavi company could be almost anything—it could manufacture garden hoses or electrical transformers. What are the odds that this is the same company that peddled Viavi Capsules, Viavi Cerate, and Viavi Royal a century ago?

What exactly does Viavi Brand Products of Lafayette, California, make?

“Herbal bitters,” she chirps. “Liquid calcium, and cerate…”

- See “Early Years in San Francisco” by Helen Perrin, at sunsite.berkeley.edu:2020/dynaweb/teiproj/ef/ [link defunct—Eds.].

- Their land holdings are described in Herbert Law’s obituary in the San Francisco Chronicle, 19 January 1952.

- This “everyone’s ill” approach runs throughout Viavi Hygiene; the lecture ploy is described in the 14 July 1906 Collier’s magazine.

- Emphasis added.

- Viavi recruitment was similar to that great American humbug Amway, superbly explained by Matt Roth in The Baffler, issue 10.

- See sfmuseum.org/1906.2/lafler.html

- “The Viavi Treatment: Its Promoters and Its Literature.” California State Journal of Medicine, April 1907 (vol. V, no. 4), pp. 73-79.

- See volumes 1 (1912) and 3 (1936) of the AMA’s series Nostrums and Quackery and Pseudo-Medicine, by Arthur Cramp.

Paul Collins edits the Collins Library for McSweeney’s Books and is the author of Banvard’s Folly and the forthcoming Sixpence House. He lives in Portland, Oregon.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.