Finders Keepers

On the history of prodigies

Michael Witmore

Whenever I look at rare book auction catalogues, I feel an odd, sentimental kind of despair. Old volumes appear in inventories like basketed children, newly delivered from some ancient stream. Just as the bundles come within reach, they disappear into the anonymous hands of a collector or the stacks of a research library. They go on to careers as precious objects or simply sit there in the rushes, waiting for someone to pick them up.

As an academic, I am used to this feeling. I don’t buy old books; I read them. But that doesn’t mean I don’t occasionally want to pluck them from the stream, especially when they are as fabulous as the book I saw up for auction recently:

BEAUCHASTEAU, FRANÇOIS MATHIEU CHASTELET DE.

La Lyre du jeune Apollon, ou la Muse naissante du Petit de Beauchasteau. Paris: [Nicolas Foucault] for Charles de Sercy & Guillaume de Luynes, 1657.

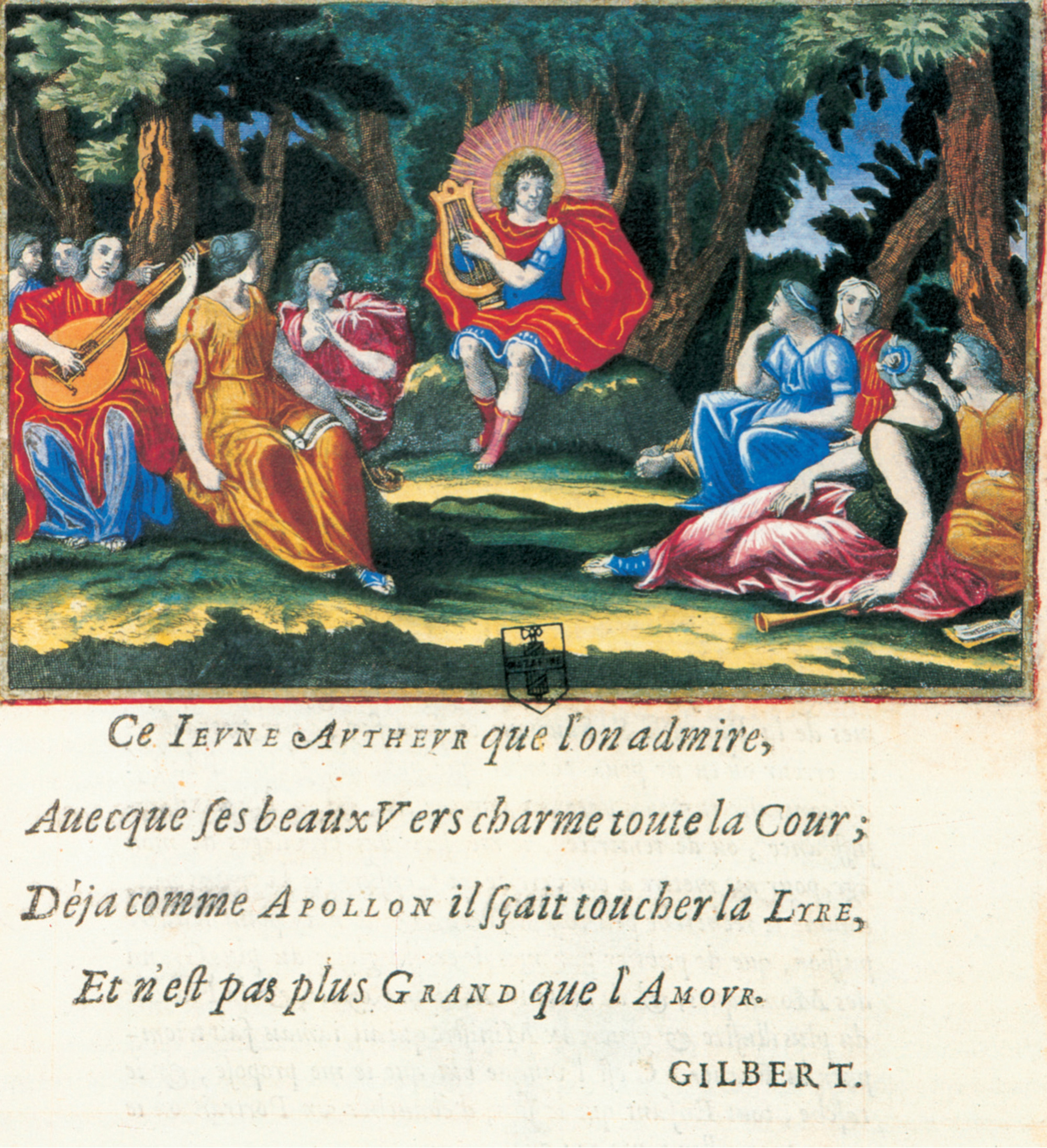

Two parts in one volume, 4°, [45] leaves (including engraved title, engraved frontispiece representing the author at age 11, and printed title in red and black), [1] leaf (half-title), 280 (numbered 262) pp.; [4] leaves, 143 (numbered 127), [1] pp., [9] leaves, and 26 engraved portraits, one half-page allegorical plate and two armorial headpieces. Modern full calf blindtooled in period style; mounted on title verso is the armorial bookplate, dated 1701, of Algernon Capell, earl of Essex, Viscount Maldon, and Baron Capell of Hadham; the Lucius Wilmerding copy (his sale, New York, 29 October 1951, Lot 84). One quire browned due to quality of paper.

FIRST EDITION of this remarkable collection of poems in praise of the most eminent men and women of the time, composed by the author between the ages of 8 and 12.

When you want a book, the argot of its description becomes irresistible in its clinical precision. “Leaves,” “frontispiece,” “quire,” and—prepare yourselves, bibliophiles—a period, full calf cover that has been “blindtooled.” (I imagine some Tiresian artisan-sage working steadily in his bookbindery…) At this point, it doesn’t really matter that “one quire is browned due to the quality of paper.”

The author of the volume, known in French as “Le Petit de Beauchasteau,” was one of the most celebrated child poets of the 17th century. I came across the description of his book by accident while doing research on child prodigies in 17th-century England. The French craze over “Le Petit de Beauchasteau” was matched, it turns out, by his enthusiastic reception in the English court in 1658. Apparently the child, then 13, was one of the favorites of Lord Protector Cromwell, the Puritan general who governed England during the aftermath of the Civil War. The English court invited the child (along with his father or perhaps an ecclesiastical “keeper”) to visit London that year, where the boy flattered his hosts by abjuring the Catholic religion. Cromwell was deeply impressed with the boy and wanted to keep him in London. But “Le Petit de Beauchasteau” slipped through his fingers and returned to France. Three years later he disappeared, a young poet who had had his day in the sun and then toppled off the map before reaching the tender age of 15. Later it was rumored that “Le Petit de Beauchasteau” made his way to Persia, which for “Enlightened” Europeans stood nearly at the vanishing point of myth and history.

The book, on the other hand, still exists (and has not, as far as I know, been purchased). For a mere $2,500, you can “own” what Cromwell could never quite get his hands on: the legacy of a youth who possessed both virtuosity and courtly fame. In doing so, you would join an illustrious line of keepers who may have pondered the mystery of the child’s disappearance while studying the engraved portraits of 17th-century “worthies” that are interspersed among the poems. Particularly striking is the brightly colored frontispiece that depicts the author, at age 11, as the young Apollo surrounded by adoring (if somewhat startled) muses. In the background, just to the right of the child’s strangely glowing head, one can glimpse the stand of Olympian woods through which “Le Petit de Beauchasteau” must have crept on his way to oblivion.

The possibility of true disappearance, forestalled by the existence of this pretty little book, was just as real for other child prodigies of the age. Christian Henri Heinecken, for example, the “wunderkind” from Lübeck, was only three and a half when he amazed the king and queen of Denmark with his elegant disquisitions at court. At the time of his death (age four), Christian had studied sacred and profane history, geography, genealogy, anatomy, French, and Latin. In an image commemorating his demise, the young genius sits at a writing desk while a skeleton reaches over his shoulder to grasp a paper that reads: vivitur ingenio, cetera mortis erunt (“through genius one lives, all the rest will pass away”). Like the young Apollo, the child from Lübeck is destined to fade into the mist, but perhaps the legend of his accomplishments will remain. With a little help from death, he will hop off the high-backed chair and step smartly into the garden behind him, never to return.

• • •

Children, like legends and rare books, are often on the verge of disappearing, and it is for those who have left the kingdom of childhood—that high-walled garden whose gate has always been left swinging in the background—to wonder where they’ve gone. Perhaps this is why a book like La Lyre de jeune Apollon commands such a high price today. Granted, prices for 17th-century books are already high because of their obvious historical value. But La Lyre is of particular interest to cultural historians because it documents another age’s fascination with marvelous events and persons. Seventeenth-century libraries were full, in fact, of books and pamphlets breathlessly describing fiery armies gathering in the sky, corpses speaking out against their murderers, and children prophesying in the middle of the night in strange tongues. The 17th century was not afraid of marvels; they were the tabloid stuff of gossip as well as the elevated subject of scientific inquiry.

It is said, for example, that King Charles I was thrilled to examine a man who had been brought to court to prove William Harvey’s theory of the circulation of the blood. The man’s chest had been blown open in battle, but the wound had healed without entirely closing. At the direction of Harvey, the king carefully placed his fingers inside the wound to feel the beating heart, which thanks to a paucity of nerve endings was virtually anaesthetized. (The story may be apocryphal.) We also hear stories of Robert Hooke—a celebrated member of London’s Royal Society—combing the woods for pieces of glowing tree bark in order to demonstrate the phenomenon of phosphorescence. Prodigies of all sorts were the prizes of curious minds, a reward for looking beyond the usual course of events for something truly spectacular.

A man whose beating heart can be touched with the hand. A piece of bark that glows in the night. A child who writes and rhymes like an adult. Such phenomena were not so different for early modern Europeans. Child prodigies were yet another example of the way in which nature (via human reproduction) could occasionally surprise observers by producing something unusual. Like comets in the night sky, ultra-precocious children were a startling aberration from the “usual course of nature,” even if their overzealous parents were the most visible cause of their appearance on the world stage. But it seems that such extraordinary talents were destined to fade. While many prodigious children grew up to become even more talented adults—witness Mozart’s dizzying ascent in the European courts—any particular childhood would always be on the wane.

How long can a child prodigy remain a child? “Le Petit de Beuachasteau” may have been destined to disappear into an imaginary Persia, since it was only there that his fabulous talents could be preserved without parallel. But, just as easily, his childhood could have been understood as already passed, since prodigious children were already adults in crucial ways. As one of his admirers wrote in the volume:

A le voir, on le croit enfant,

A l’ouïr, on voit sa vieillesse.

[To see him, one would think him a child,

But hearing him, one recognizes that he is old.]

The idea that children already possessed the knowledge and experience of those far older was already ensconced in the literature of the middle ages. Centuries before Wordsworth declared the child father to the man, medieval writers were celebrating the character of pueri senes or “wise children” who had superior powers of reasoning and theological discernment. Quite often it was the young Jesus who was the source of this image. The adolescent deity, confidently lecturing his skeptical audience on the steps of the temple, illustrated for medieval readers the sovereignty of knowledge when it was uncorrupted by sophistry or greed.

A series of child preachers and prophets would follow in the God-child’s ancient footsteps throughout the late 17th and 18th centuries. When rural Protestants in France lost their nerve and converted to Catholicism, for example, their children berated them in the middle of the night with long sermons about righteous long-suffering. Like conduits for unconscious guilt, the rustic Enfants de Dieu or “Children of God” lectured all comers in several languages during their midnight trances, denouncing their parents to crowds of onlookers and, eventually, to doctors and ecclesiastical authorities sent from the city to investigate.

Another child prodigy, Jacqueline Pascale (sister of the mathematician Blaise), made her way to religion later in life. Also known as “Sister Euphemia” because of her piety in the convent at Port Royal, Jacqueline Pascale began as a poet who wrote her first epigrams and rondeaux at the age of twelve. Anxious to see her charge advance, Jacqueline’s benefactor financed the publication of a collection of her poems (now lost) entitled Vers de la petite Pascale [Poetry of the Little Pascale] (1638). As proof of her talents, the collection is said to have included several epigrams that the girl had composed in an ante-chamber while waiting to meet queen Anne of Austria. Suspected as an imposter, the young poet was asked to demonstrate her talents to the ladies of the court at St. Germain before she could be presented to the monarch in person. She acquitted herself handily with the following poem, composed spontaneously for a Madame de Hautefort:

Beau chef-d’oeuvre de l’univers,

Adorable object de mes vers,

N’admirez pas ma prompte poésie.

Votre oeil, que l’univers reconnoît pour vainqueur,

Ayant bien pu toucher soudainement mon coer,

A pu d’un meme coup toucher ma fantasie.

[Beautiful masterpiece of the universe,

Adored object of my verse,

Do not admire my impromptu poetry.

Your eye, which the world recognizes as its conqueror,

(Able to strike suddenly at my very heart)

Was able, in the same stroke, to touch my imagination.]

Once admitted to the royal audience, Jacqueline became the darling of the royal couple and her verses survive in letters describing her exploits. She also proved a charming actress, a skill which proved invaluable a year later when—while acting in a child troupe for the powerful Cardinal Richelieu—Jacqueline utterly charmed the man who had recently taken measures against her father for sedition. “Voilà la petite Pascale,” the Cardinal exclaimed when she approached him (somewhat timidly) after the performance. Standing before the great eagle-eyed prelate, she recited the following poem:

Ne vous étonnez pas, incomparable Armand,

Si j’ai mal contenté vos yeux et vos oreilles:

Mon esprit agité de frayeurs sans pareilles,

Interdit à mon corps et voix et mouvement,

Mais pour me render ici capable de vous plaire,

Rappelez de l’exil mon miserable père.

[Do not be shocked, excellent Armand,

If I have not contented your eyes and ears:

My soul, troubled with incomparable fears,

Has inhibited my body, voice and gestures,

But if I am capable of pleasing you here,

Recall from exile my miserable father.]

The voice of the young poet apparently melted the Cardinal, who ended up inviting her father to return from hiding without fear of harassment. (Why don’t the publicly disgraced enlist children in the project of public rehabilitation today? Where are the cherubic defenders of Martha Stewart and Kenneth Lay?)

Jacqueline’s remarkable encounter with Richelieu can be repeated only because it appears in books—the true keepers of childhood. Books grow old but they stay the same, and like the impromptu poetry of “La petite Pascale,” they lead their keepers back to the unsupervised nurseries of legend. Perhaps this is why Jacqueline, Henri, and Matthieu de Beauchasteau became more poignant as child prodigies when their exploits were connected with “lost volumes” or “rare editions.” Those volumes became pathways, lines of flight: swinging gates to ancient gardens that had been summarily abandoned.

But what of the adults who read, write and collect these books? These exiles from the garden are an inverted form of the wise child—aged in years but precociously infantile, attached to desires that cannot be fulfilled in the wide, wide world of adulthood. Consider, for example, the life of Victor Cousin, a 19th-century philosopher and scholar who collected all available records of Jacqueline Pascale’s performances and assembled them in a volume entitled, Jacqueline Pascale: premiéres études sur les femmes illustres et la sociéte du XVIIe siècle [Jacqueline Pascale: first studies of famous women and the society of the 17th century]. Cousin was as an intense man who, according to some, was romantically obsessed with one of his older and more risqué 17th-century subjects, the Duchess de Longueville, also known as the “sinner of the Fronde.” Once the editor of the works of Descartes and Plato, Cousin spent the later years of his career chronicling famous and infamous females of the 17th century. The Paris wits registered their disdain of Cousin’s barely concealed longing with the mock epitaph: “Here lies Victor Cousin, the great philosopher, in love with the Duchess de Longueville, who died a century and a half before he was born.” Perhaps he should have stuck with lecturing on truth and beauty.

In the albumen print portrait of Cousin that resides in the Getty collection, any trace of whimsy or sentiment has been banished. The philosopher’s right hand is tucked, like the Emperor’s, into the side of his buttoned suit. He is the visual opposite of the child prodigy: aging, grim, marked by the knowledge that life is short and scholarly work is long. Like Richelieu, Cousin seems to possess an implacable, probing eye. Here is the finder of lost words, the curator of childhood past. “Whatever is lost in childhood” his expression seems to say, “can be found again.” But found where? In books of course, like the one about “La petite Pascale.”

When Cousin sits down to write his biography of young Jacqueline, he is creating an object that has already, in some crucial sense, gone missing. Books, like any particular childhood, are precious because they are only passingly present. They are written, in fact, at the moment when their contents are about to disappear. Which is why Cousin’s attempt to retrieve Jacqueline’s life and poems is so beguiling, even if it is ultimately misguided. He knows that books are tangible things—they have blindtooled covers, glorious illustrations, faulty bindings and missing pages—whereas childhood and memory are not. In the face of oblivion, the facts of youth must be gathered, accounts must be made. “La petite Pascale” will reach out to her audience once more, he thinks, this time from the bending leaves of a philosopher’s tome.

Bibliography

François Mathieu Chastelet de Beauchasteau, La Lyre du jeune Apollon, ou la Muse naissante du Petit de Beauchasteau (Paris: [Nicolas Foucault] for Charles de Sercy & Guillaume de Luynes, 1657). For sale by E. K. Schreiber.

Victor Cousin, Jacqueline Pascale: premiéres études sur les femmes illustres et la sociéte du XVIIéme siècle (Paris: Didier, 1869).

Victor Cousin, Madame de Longueville: la jeunesse de Madame de Longueville (Paris: Didier, 1853).

Victor Cousin, Du Vrai, du beau et du bien (Paris: Didier, 1853).

Michèle Sacquin, ed., Le Printemps des geniés: les enfants prodiges (Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale/Robert Laffont, 1993).

Michael Witmore teaches English at Carnegie Mellon University. His book, Culture of Accidents: Unexpected Knowledges in Early Modern England, was just published by Stanford University Press.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.