Melchers’s Ghosts

Monica Black

In the spring of 1953, a former Nazi named Anton Melchers, who in the Third Reich had been a newspaper editor, war reporter, and—according to his brother—talented propagandist, was admitted to the university psychiatric clinic in Heidelberg. His brother, a former high-ranking SS officer, brought him there because Melchers had stopped eating. At the clinic, Melchers reported hearing voices that accused him of sexual immorality and intimated that he would be “paraded” in the streets. Melchers was also preoccupied, his brother said, with anxieties about being “rounded up and taken away” as punishment for his National Socialist past.[1]

Melchers was in his early fifties and had no history of mental illness. He was highly educated and held a doctorate. But after the war, he lost his job as a reporter during denazification, a series of measures the Allies took in an effort to purge the former political order. He found it difficult to restart his life. He opened a residential hostel in Heidelberg with his mother, which he continued to run after her death, but that too went sour. After he kicked out an unmarried couple for “immoral” behavior, the former tenants retaliated, accusing Melchers of illegally permitting “nightly visitors,” a charge with overtones of sexual impropriety.[2]

Melchers’s is, perhaps, a story of mental illness, but it is also more than that, given that it unfolded against the backdrop of the Third Reich’s recent defeat. That event unleashed deep and enduring tensions in West Germany, and provoked fears of retribution and counter-retribution in a society awash in suspicion and bad blood. Denunciation had been commonplace in Nazi Germany. Citizens were encouraged to betray to the state those who defied the regime’s edicts (by violating, for example, the myriad racial laws aimed principally at Jews) or whom they suspected of disloyalty (because they refused to return a neighbor’s stiff-armed “Hitler greeting” or listened to foreign radio broadcasts.)

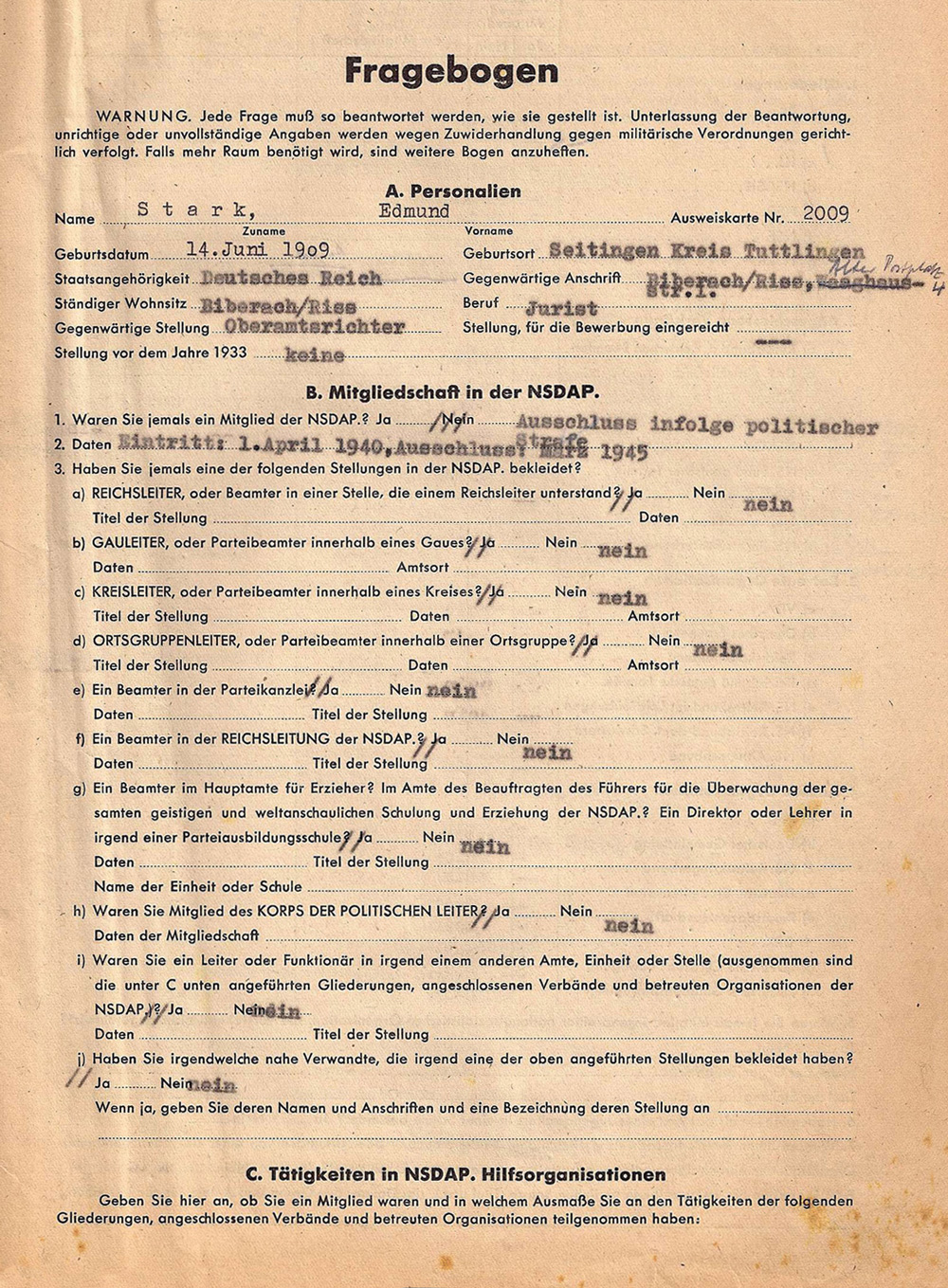

Then the Allies came, and a whole new layer of distrust and unease descended. Allied troops did not just blow up Nazi monuments and hack swastikas and offensive slogans off building facades; they also issued questionnaires and convened civilian tribunals to determine individuals’ degree of involvement in the Hitler regime, sorting the population into different categories based on their relative complicity. Those considered dangerous sometimes served time in internment camps. Those deemed less culpable were conscripted to clear rubble and their standard allotment of rations was reduced according to a calculation that depended on the category to which they had been assigned. As was true in Melchers’s case, individuals could be relieved—at least temporarily—of their civic rights and their employment, occasioning a considerable loss not only of income but also position and social prestige.

Denazification prompted less soul-searching than resentment and anxiety among the German population. People worried that their prior affiliations and involvement in everything from war crimes to far less nefarious acts—like having obtained property illegally during the Nazi years—would be revealed. That they would lose their jobs. That they might be prosecuted. That they would be unmasked, exposed. Melchers would almost inevitably have associated the regional occupying force, the United States, with both Germany’s humiliation and his own loss of power, and it is not inconsequential that he imagined that the proximate cause of his trouble was that one of his tenants had in fact had some Americans stay overnight, visitors whom he had promptly expelled. These particular Americans, Melchers was sure, had facilitated his downfall. Nor is it insignificant that the voices Melchers heard told him he would be publicly shamed, “paraded” in the streets for some ill-defined indiscretion. And, in a striking deflection, he worried that he would be rounded up and taken away, as Nazis like him had rounded up and taken their victims away.

Early West German social unease was so pervasive and so bad that even after the newly formed Federal Republic passed into law in 1949 a general amnesty protecting citizens from prosecution for various Nazi-era crimes, a conservative Protestant weekly called Christ und Welt referred to a gathering civil war. That civil war manifested itself, the journal’s editors explained, in the nagging possibility that an acquaintance—maybe a neighbor, a coworker, or even a friend—might decide to inform authorities about what one had done during the dark days between 1933 and 1945.[3] And the malaise lingered. Well over a decade after the war, in a blistering 1960 essay called “The Frozen Country,” US literary scholar John McCormick referred to “the isolation of German from German in what passes for society.”[4] The Germans “are a frenetic people,” McCormick continued. “Small incidents are inflated into tragedies; hypochondria prevails, and anything can lead literally to anything. The Germans are a haunted people, haunted by the recent past, by guilt, and by fear of the future both immediate and remote.”[5]

Melchers’s tale gives us a glimpse into the haunted world McCormick described, a world of post-Hitler spiritual and psychological distress. Usually carefully hidden within families or among intimates, this distress could sometimes burst into public view in unaccustomed and unaccountable forms. Melchers’s doctors, for example, had a hard time diagnosing his trouble. Some of the voices he heard accused him of “whoring,” though he insisted that he was celibate. He believed he was being watched. His strained nerves made him oversensitive to noise and light, and sometimes he had to clap his hands over his ears to block out “acoustic hallucinations.” Doctors wondered first whether he might be psychotic. Then schizophrenic. Then they put him under electroshock, dosed him with insulin, and decided that he was suffering from brain atrophy.[6]

And yet: perhaps Melchers’s diagnosis was made more difficult because his symptoms were not just internal to him, the signs of a mystifying personal illness. They were symptoms, if one will, of history, and of a malaise at once personal and social. The historian of medicine Anne Harrington describes instances of “bodies behaving badly”—when an ailment’s origins, rather than being rooted in individual physiological, biological, or psychological factors, may instead arise from social experience.[7] Some contemporaries would have agreed. Though his own experience was vastly different from that of a Nazi like Melchers, novelist Thomas Mann observed that many of his fellow German exiles bore physical signs of their social alienation. They “seemed to be particularly susceptible” to “heart attack, in the form of coronary thrombosis or angina pectoris,” Mann wrote. Considering the grief and horror of their experiences, he continued, this was “scarcely to be wondered at.”[8] Mann also once referred, and not just metaphorically, one suspects, to the “heart-asthma of exile.”[9] As Harrington (along with some medical anthropologists) has proposed, experiences of “betrayal, interpersonal alienation, and power politics” may help account for certain manifestations of illness or sudden disability.[10]

In fact, Melchers was far from being the only person whose maladies doctors could not cure or even identify in postwar, post-Hitler Germany. The case of Bruno Gröning—who gained a mass audience as a spiritual healer—reveals that huge numbers of people found themselves suddenly struck by forms of paralysis, as well as deafness and blindness, after 1945. A refugee from the formerly German city of Danzig (today’s Gdansk), Gröning had been a solider and rank-and-file Nazi party member. He first came to national attention in 1949 when he was called to the bedside of a small boy who no longer had the strength to stand. Within a short time of meeting Gröning, the boy suddenly got up for the first time in many weeks. This event touched off an enormous response, sending tens of thousands of people on pilgrimages—first to the town of Herford, where the boy and his parents lived, and then to other locations up and down the country where Gröning appeared to enormous crowds. Gröning began being widely referred to as a “wonder doctor” (Wunderdoktor), or miracle healer. Such was his reputation that one woman wrote asking if he would raise her friend from the dead.

Gröning seems to have had particular success treating those experiencing sudden paralysis (of the legs, hands, feet) and other ailments whose reality doctors rejected or which they found impossible to remedy. And yet, again and again, in gatherings around Gröning, individuals who had suddenly lost their ability to walk discovered just as suddenly that they no longer needed their wheelchairs or crutches. A veteran, a former party member, a refugee: he was like them, but special. He understood their situation. He appeared to them to be a figure of a trust otherwise sorely lacking in society. But he also diagnosed their situation to be the result of spiritual emptiness: a turning toward evil and away from God.

Gröning was not alone. A number of wonder doctors achieved significant popular resonance in the 1950s. And there were also fiery evangelist-healers like Hermann Zaiss, a razor-manufacturer-turned-preacher. Zaiss exhorted the huge crowds who came to hear him preach to repent their sins, and linked widespread illness to collective wrongdoing. “Misfortune, plagues, pestilence, sickness of every kind … can come over a whole nation according to the Holy Scripture,” Zaiss warned. More trenchantly still, Zaiss prophesied that whatever one’s individual acts in the Hitler years had been, the entire nation would have to reckon “with what the community as a whole had earned.”[11] According to Zaiss, sickness was not just a physical condition in post-Nazi Germany. It could also be a metaphysical state, and a spiritual sign: evidence of a curse, of cosmic disfavor, of wickedness and the refusal to atone for it.

If forms of sickness can grow out of a generalized mistrust, profound social alienation, and a gnawing sense of failure and shame, then the question we might most fruitfully ask is not so much “did Bruno Gröning cure people?” as “what was Gröning curing?” Many of those who came to see him talked about how much they trusted him, in ways that they did not, perhaps, trust their doctors. Physicians were heavily implicated in the eugenic policies of the Third Reich and helped carry out hundreds of thousands of state-mandated sterilizations and “mercy killings.” In sharp contrast to the instrumentalist, technocratic form of medicine practiced in Nazi Germany, Bruno Gröning’s supplicants found relief from their afflictions, they said, just by being near him.

• • •

If you have never heard of this aspect of postwar German history, that’s in part because there is no archive of spiritual malaise induced by catastrophic defeat or fears of your past coming back to haunt you, the way that there are archives for political parties and institutions of state. Stories like Melchers’s sit in some folder somewhere, in a box, on a shelf in storage, but they have to be discovered, which happens mostly by accident, if at all. When they are found, it is usually amid other documents, ones that have seemingly little to do with the history of Nazism and the longer-term social effects of its defeat in Germany. Melchers’s story, for example, was discovered by psychology professor Dr. Viola Balz when she was doing research on 1950s drug trials for the early psychopharmaceutical chlorpromazine.

Denazification—the measures enacted by the Allies to root former Nazis out of positions of power and influence and to strip Nazi ideas, symbols, law, and language out of public discourse—is largely considered by historians to have been a failure. Yet the hundreds of thousands of people who gravitated toward figures like Zaiss, Gröning, and other postwar wonder doctors suggest ways that it actually may have succeeded—albeit in a perverse way.[12] Taking Melchers’s case as an example, we can see how the past came back to haunt him even as he (and his doctors) bracketed its significance and projected fears of his persecution onto his tenants. Denazification may not have been entirely successful in its effort to drive former Nazis out of public life. But fears that their ghosts would catch up to them may have caused some—like Melchers—to lose not just their jobs, but their minds.

- Viola Balz unearthed Melchers’s story while conducting archival research for her article “Terra Incognita: An Historiographic Approach to the First Chlorpromazine Trials Using Patient Records of the Psychiatric University Clinic in Heidelberg,” History of Psychiatry, vol. 22, no. 2 (June 2011), p. 188.

- Ibid.

- “Die kleine Amnestie,” Christ und Welt, vol. 3, no. 2, 12 January 1950, p. 2. Cited in Norbert Frei, Adenauer’s Germany and the Nazi Past: The Politics of Amnesty and Integration, trans. Joel Golb (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), pp. 19–20.

- John McCormick, “The Frozen Country,” The Kenyon Review, vol. 22, no. 1 (Winter 1960), p. 36. Great thanks to Till van Rahden for recommending McCormick’s essay.

- Ibid., pp. 57–58.

- See Viola Balz, “Terra Incognita,” pp. 190–192.

- Anne Harrington, The Cure Within: A History of Mind-Body Medicine (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 2008), p. 251.

- Thomas Mann, The Story of a Novel: The Genesis of Doctor Faustus, trans. Richard Winston and Clara Winston (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1961), p. 76.

- Cited in Sean A. Forner, German Intellectuals and the Challenge of Democratic Renewal: Culture and Politics After 1945 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), p. 60.

- Anne Harrington, The Cure Within, pp. 253–254.

- Hermann Zaiss, Gottes Imperativ: Sei Gesund! (Marburg an der Lahn: Verlagsbuchhandlung Hermann Rathmann, 1958), p. 43. My translation.

- Svenja Goltermann makes a similar argument in her book The War in Their Minds: German Soldiers and Their Violent Pasts in West Germany, trans. Philip Schmitz (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2017), pp. 90–92.

Monica Black is a historian of twentieth-century Germany and central Europe. She is the author of A Demon-Haunted Land: Witches, Wonder Doctors, and the Ghosts of the Past in Post-WWII Germany (Metropolitan Books, 2020) and Death in Berlin: From Weimar to Divided Germany (Cambridge University Press, 2010). Black teaches at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, and is editor-in-chief of the journal Central European History.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.