Hell Is for White People

A painting from 1515 turns a mirror on its viewers

Alexander Nagel

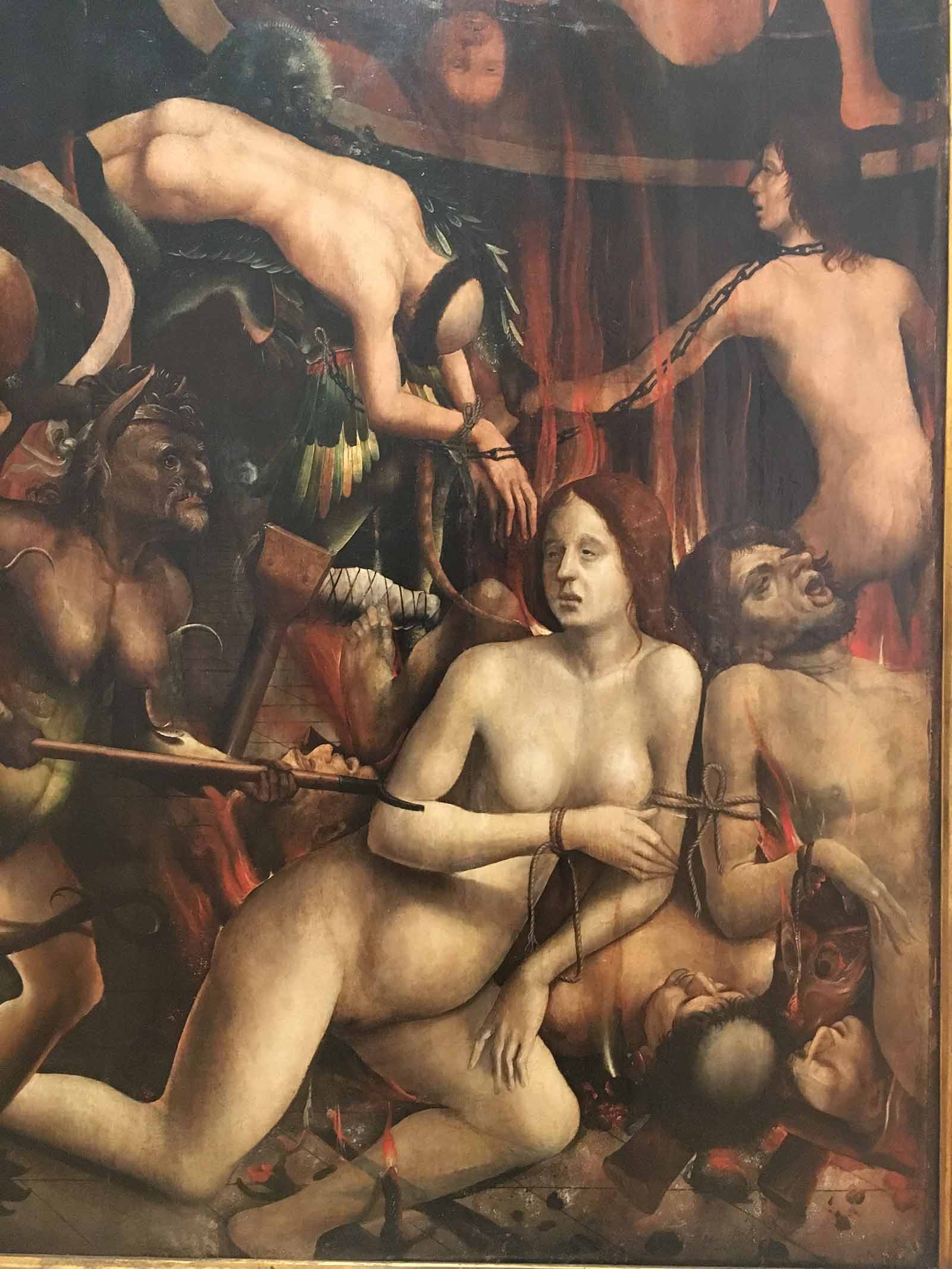

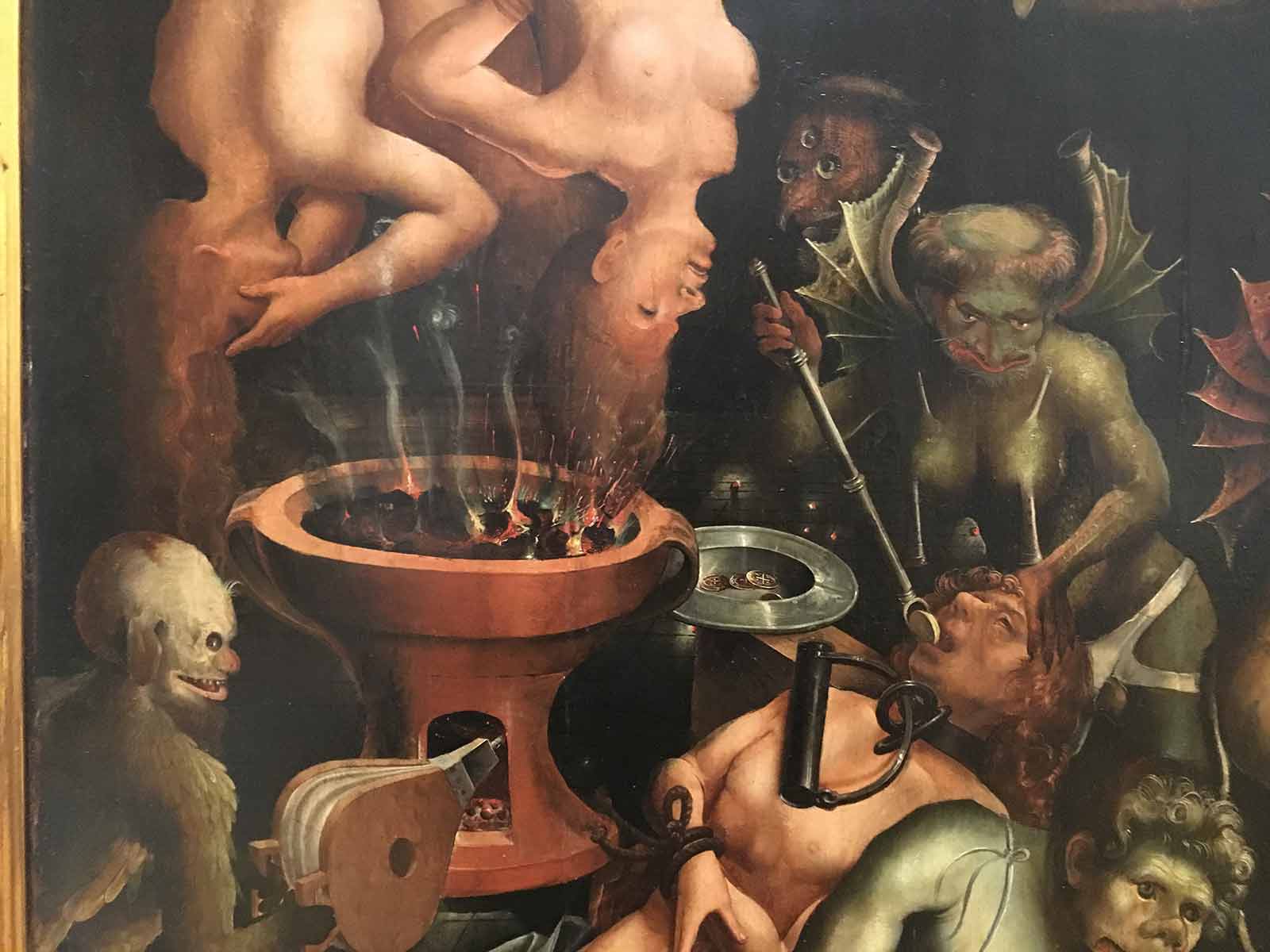

Naked people are tumbling into the picture through a circular opening at top right, their features immediately blurred by rising heat and smoke. Below, various bodies are being put to the flames, a traditional punishment for those consumed by lust in their lifetimes.

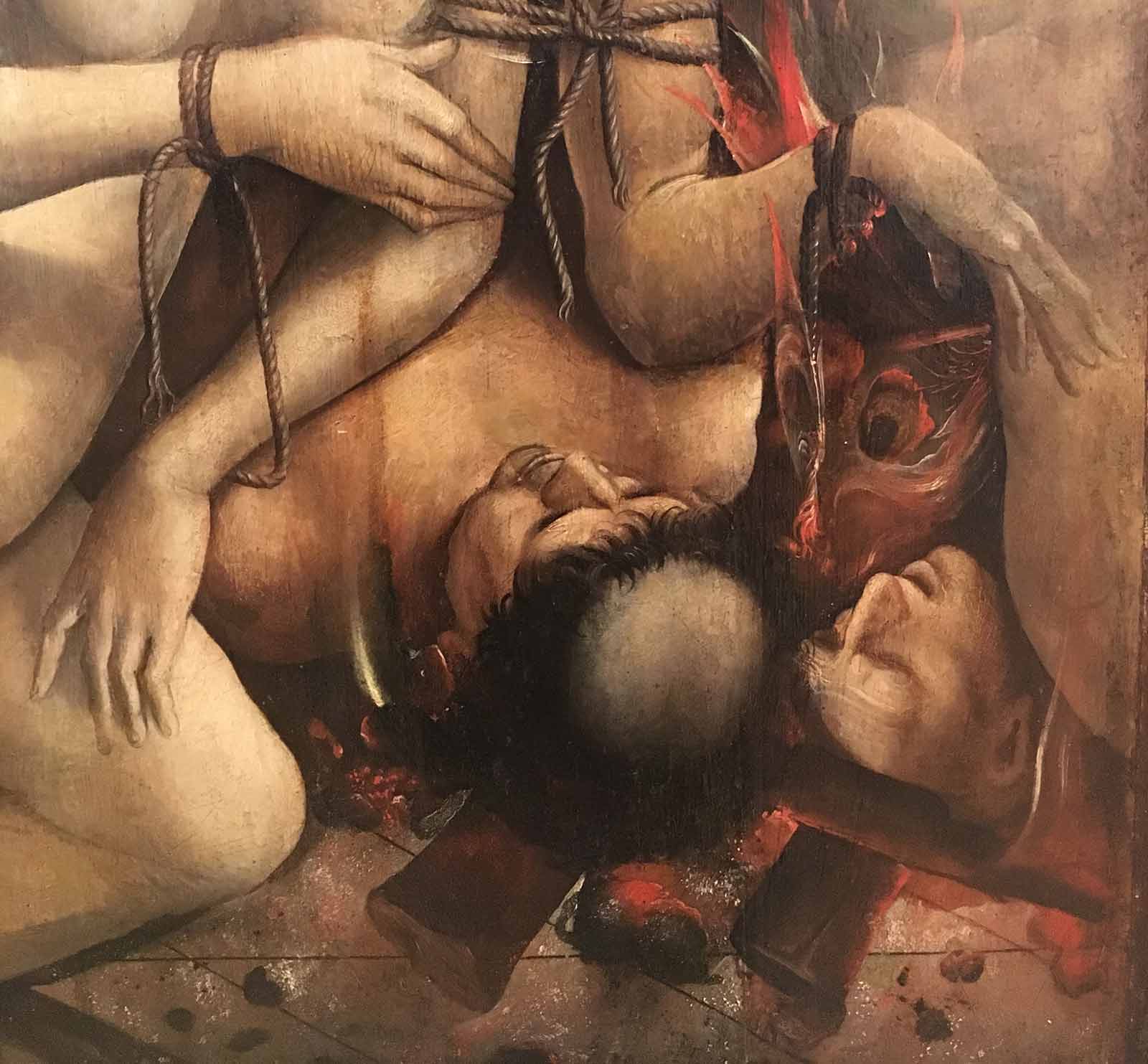

A screaming man deeper in the flames is bound to a woman whose genitals are clearly on view. She is being prodded toward the flames by a bearded, hook-nosed devil with pendulous breasts and curved spikes sprouting from his armor. Under the naked couple, we see the tops of two heads, one of them tonsured like a monk or friar, their bodies lying flat on kindling that is catching. Between their heads, the flames coalesce into a glowing mask-like figure. We bend forward to try to get a visual handle on it—is it flame or face or mask?—only to find an expression of open-eyed horror mixed with fascination, a mirror to our own.

Above the bound couple, a demon carries one body over his shoulder and leads another by the hand, though the prisoner is already chained around the neck. Taking his two captives from the flames toward fresh tortures in the center of the picture, the demon’s rodent-like face looks left, a rictus revealing sharp teeth. He shows his backside, his tail toward us, and we see that his left leg appears to be in a cast, bent at the knee, resting on a crutch. Prosthetics come naturally to these creatures. He is covered in feather-decorated armor, or maybe the feathers just belong to him. He wears a helmet made of a ferret-like animal looking backward and apparently vomiting blood, or maybe he just has two faces, front and back.

In a cauldron at the center—matching in size the oculus upper right, as if they were fitting pieces that have slid apart—three friars and two women languish in boiling liquid that is actively releasing bubbles and steam. A traditional punishment for greed, here it is notably applied to three men who belong to religious orders. The basin hangs on three chains, descending from an unknown vault above. Three of the five figures look up toward this height as they struggle to breathe. Below them the fire crackles, sending sparks into the air.

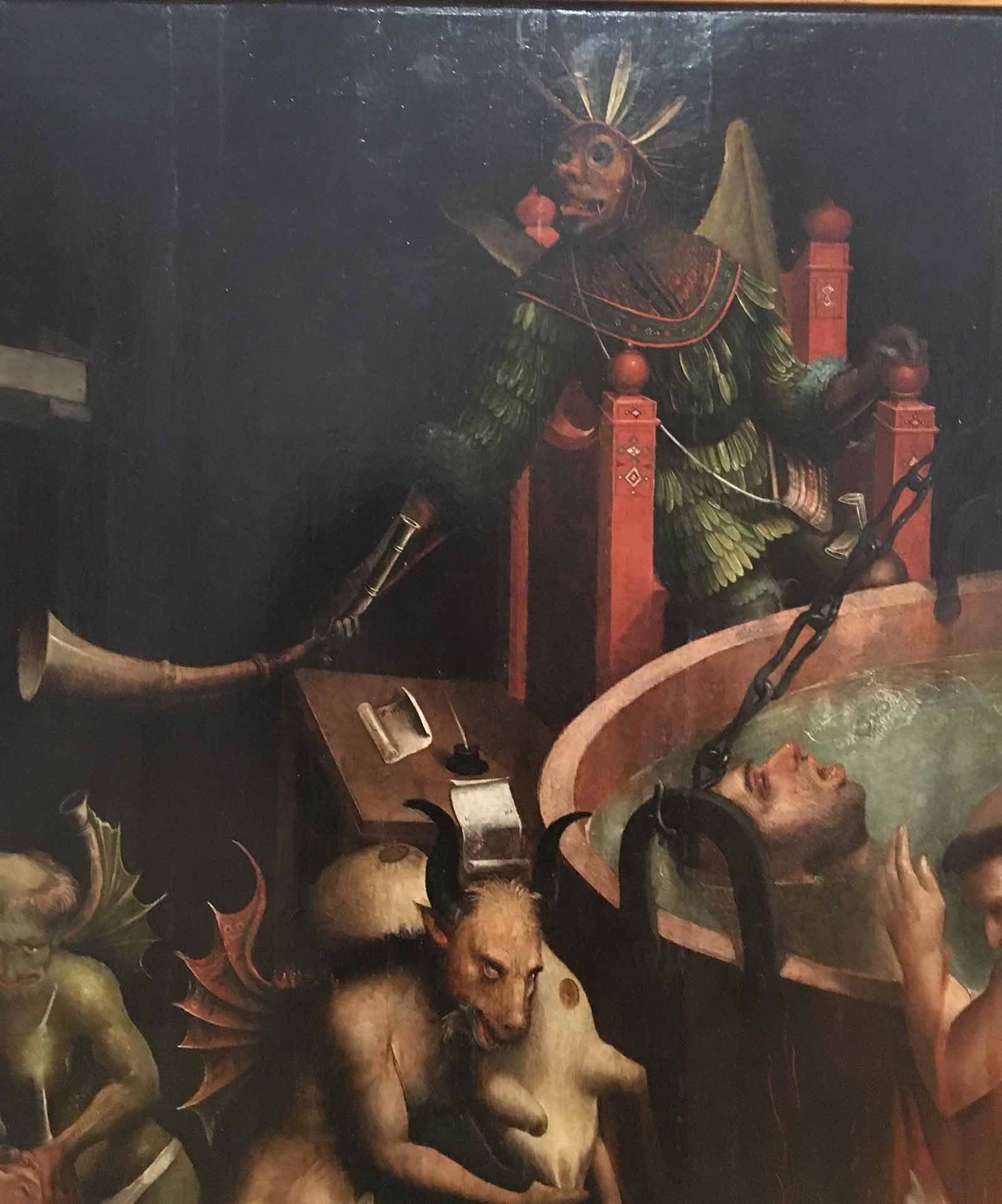

The Devil, presiding over the scene, sits on a throne that has been identified as West African. His mask-like face with wide-open eyes turns toward his right, our left, as does his right hand, which brandishes an ivory horn similar to ones from the Ivory Coast that had already reached Portugal.

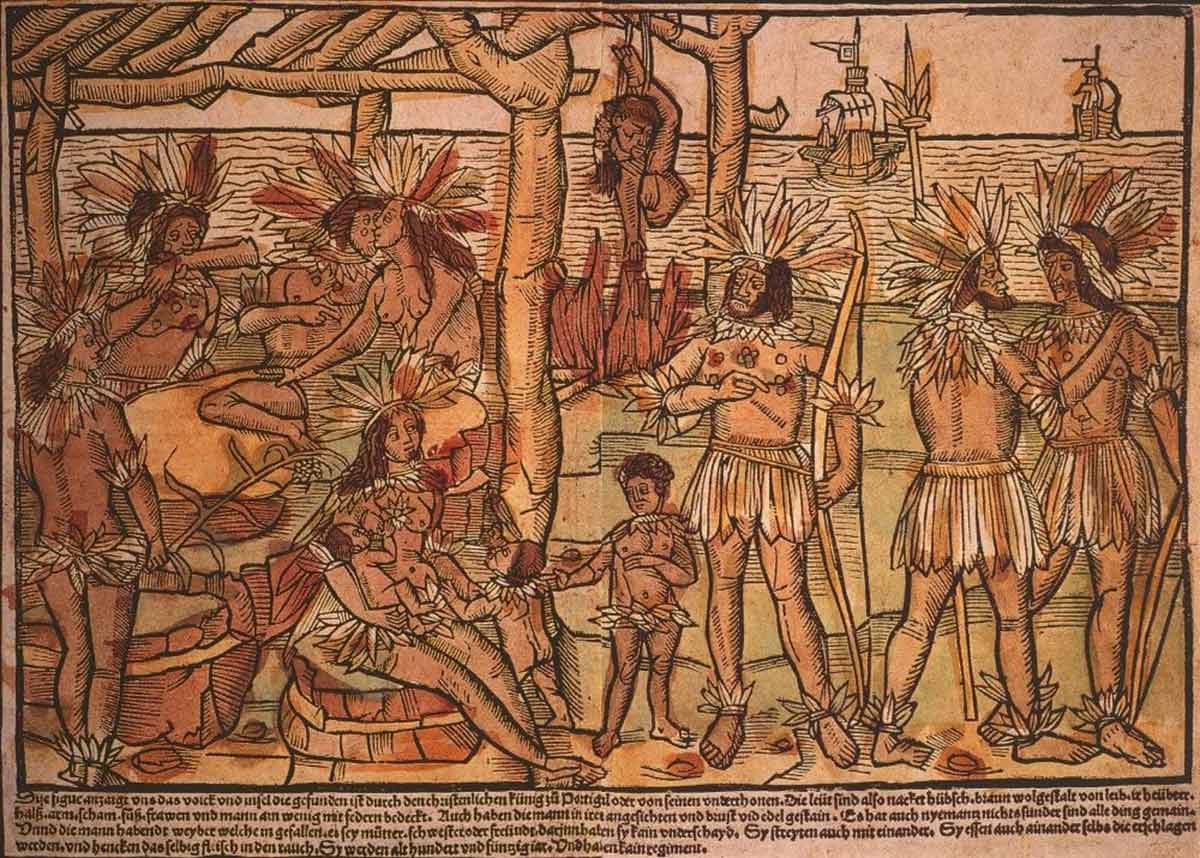

The Devil wears an elaborate suit of feather armor, as well as a feather headdress that strongly resembles those of the Tupi natives of Brazil, already famous in Europe for their reputed cannibalism, free sexuality, and open social structure, without hierarchy, marriage, or money.

Around the Devil’s shoulder is a purse with red and white decorations. On his left knee is a folded piece of paper. On the table to the right is an inkwell with a pen and two paper scrolls with undecipherable writing on them, accounts of a sort that we will never understand. This Devil is a foreigner, an amalgam of the peoples encountered (and dominated) on recent Portuguese voyages. But here he is in charge.

Below the table, a horned, goat-faced demon with a bird’s beak for a penis and red dragon wings with black and white decorations holds a pig’s skin over his shoulder, emptying some kind of powder (spices?) or liquid into a funnel placed firmly in the mouth of a prisoner with long flowing blonde hair who is shown gagging, due punishment for gluttony. Below him, another prisoner is being fed a lump of metal (gold?) by an androgynous demon with breasts and a sort of toga, and hand-like feet. Perhaps this is punishment for greed.

To the left, another prisoner is being punished for his greed by being fed coins at the hands of a tonsured, bearded demon with trumpets growing out of his/her breasts, and two more trumpets serving as armature for his wings, while a ragged jockstrap fails to hold a testicle. The coins going into the prisoner’s mouth are identifiable as Portuguese gold ten-cruzado coins of the period of Emmanuel I (1495–1521), with their characteristic crosses and platter-like borders. The gold in these coins came from Sudan.

Behind is a three-eyed beak-nosed demon, apparently without a body, who stares with triplicate rapt eyes (perhaps drawn from Hindu images recently encountered by Portuguese navigators?) at three prisoners suspended upside down. The hair of one of the hanging women is being consumed by the fire, while another tries in vain to protect her eyes from being burned out. These figures hang over a sort of altar with glowing fiery coals that is being stoked from below by an albino demon with a natural monochrome coat of feathers, who plies the bellows while laughing and turning truly haunting eyes toward us. Embers spit out from this altar and land on the pavement behind.

No one knows who painted this depiction of hell, or who asked for it to be made, or even what purpose it served. We only know that it was done in about 1515 in Lisbon. To my eye, the facial types resemble those of the royal painter Cristovão de Figueiredo, who died in 1525. Several of the strange motifs—the figure with bent knee on a crutch, the pig orifice, the spurting fire, the beak-nosed figure, and the albino monster—are closely drawn from a triptych by Hieronymus Bosch that was in Portugal (probably in the Portuguese royal collection) at the time, and now hangs in the same museum as this painting.

Our painting of hell is big, much bigger than you might expect from looking at a photo. It doesn’t fit clearly into any category of picture known at the time. It is an independent panel, not a scene in a fresco cycle that gains meaning from the larger program. It’s not an altarpiece, nor is it a typical private devotional image, which would have been smaller. Its oblong shape suggests it was not part of a larger structure, as in triptychs by Bosch and others, where hell occupies one compartment, one part of a larger statement about human life and the world. This is a big stand-alone painting of a subject that normally didn’t stand alone. The painting lowers you right down to the sub-basement of hell and lets you look. The looking begins as voyeuristic fascination and then sinks into self-reflection.

Does the painting demonize the peoples of Africa and America and possibly Asia by associating them with the Devil’s domain? Possibly. But it also shows white Europeans receiving due punishment, and clearly identifies them as white Europeans. There had been paintings of hell before, showing people (much like the people for whom the paintings were made) undergoing various punishments for their sins. But this painting no longer represents generic humanity. Here, the tortured are marked as white Europeans, being punished by mostly swarthy monsters with distinctly exotic trappings drawn from the newly encountered inhabitants of the farthest ends of the world—all the way down the African coast, all the way across the (Atlantic) Western Ocean, and, possibly, as far as India. And the punishments seem to concentrate on the sins unleashed by the European expeditions, the sins of rapaciousness: lust, gluttony, and greed. The monks and friars who accompanied these expeditions, tacking missionary work onto commercial exploits, are emphatically included among the damned.

The painting is full of upendings that unsettle orientation, and doublings and triplings that set off a viral logic of proliferation, presenting figures as multiples or versions of each other—the three hanging women, the several prone men, the repeated tonsured friars, etc. The viewer walks back and forth in front of it, taking in the sickening details, never quite putting it all together as a picture. An uncontained quality, enhanced by its unusually large size, makes it less like a picture than an infectious atmosphere or a fever dream. Viewing here is not distanced but self-involving, seeing inseparable from the strangeness of seeing oneself seeing. Turning the colonial gaze back on the colonizers, the painting presents the hairstyles of the Europeans, such as the tonsures, in the manner of recent European reports and images depicting the strange hair and stylings of outlandish natives. Here, Europeans themselves go naked, just as bestselling accounts were then describing the inhabitants of America, Africa, and India. Here, white people are the rapacious ones, the lusty ones, the ridiculous ones, and the defeated ones. Two faces, the albino monster to the left and the flame mask to the right, turn toward us as if to say, yes, I know you’re enjoying watching this, and have you considered this might be you?

Some images from the period—just a few—show the costs of subjection and colonization for the native populations of America, Asia, and Africa. Almost none, apart from this one, prod their viewers to imagine the costs for the colonizers themselves. Depicting Europeans as Europeans, it challenged its original viewers to ask: is this my tribe? And of its future viewers it asks, who was this tribe and what is my relation to it?

Alexander Nagel teaches art history at New York University.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.