Thing / No. 1

Your guess is as good as ours!

David Byrne, Nib Westingford, and Todd Wider

“Thing” is a column in which writers in various fields identify and describe a single found object not recognizable to the editors of Cabinet.

Not long ago, one of Cabinet’s editors found this enigmatic drawing on the streets of New York and brought it back to the office. None of us knew what it was, so we decided to ask a range of experts in various fields for their advice. Most had no idea, but three of them seemed so certain that we decided to publish their responses below.

Conveying a mild implication of antisocial, lonerish rambling, the American harmonica carries only the slightest inkling of danger passed on to it by its South American ancestors, such as the sembla. For with the harmonica, the musical and weapon functions previously linked in the instrument’s genealogical precedents reach their definitive separation. Music could now be safely contained within a non-combative vessel, or at least an instrument whose ritualistic function did not require darts. But since the rural Ecuadorian communities who constructed the sembla and practiced the rituals associated with it were eventually brought into the economic orbit of Quito (a process accelerated by NAFTA), samples have been extremely rare. Which accounts for my thrill at encountering a sembla like this one, as I myself did in my early anthropological fieldwork in Ecuador in 1964.

As you can see from the cutaway diagram, hollow shafts contained ringed, and in turn, hollowed darts with a range of protuberances. Skilled blowers could fire off a third, a half, or a quarter dart by sucking a portion of the dart into their mouths, and separating the petal-like nodules before firing. The trick was thus to continue the complex musical compositions while performing these manipulations—and trying, above all, not to swallow a dart. Master dart singers were called “dos linguas”—or “two tongues”—by those who participated in the sembla rituals, where audience participation had, of course, a more urgent sense: were any participant to slip visibly from the trance states that were the ritual’s goal, the sembla artist would, without losing a note, fire a small, hallucinogenic dart into him or her. The rush was instant, though comparatively temporary—quite unlike the eight-hour saga produced by the drug yagé, and chronicled in the letters of William S. Burroughs. Yet even 37 years ago, during my own fieldwork, Americans were already receiving permission to participate in the sembla rituals, and thereby, as my studies argued, materially changing them, blurring any understanding we might ever have had about the sembla’s precise role in these rituals.

—Nib Westingford, anthropologist

• • •

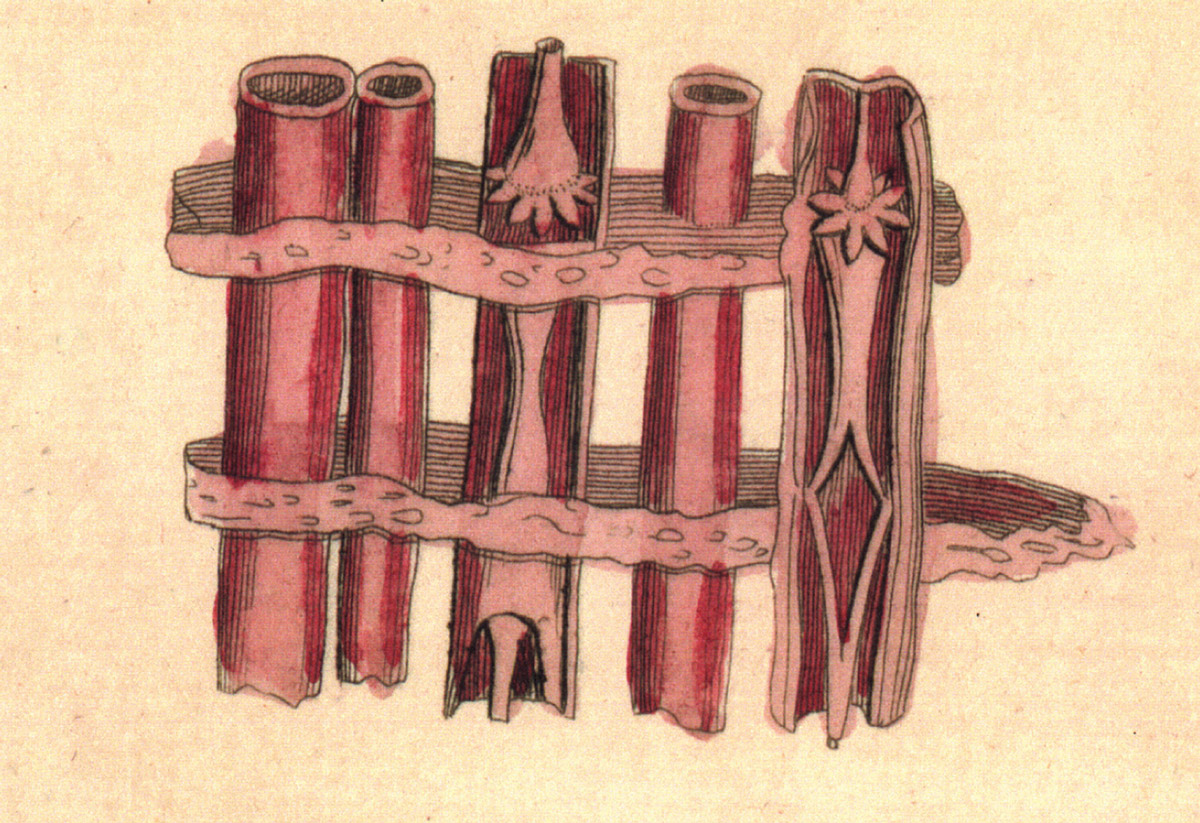

We encounter here the gross, histologic cross-section of a neurovascular bundle connecting two non-imaged body territories and traversing two depicted tissue planes. We can see the larger diametered vein adjacent to the smaller diametered artery, which bring oxygenated and deoxygenated blood back and forth between the body’s circulatory central pumping station and the periphery. A separately depicted nerve, with its epineural layer opened—peeled away, as it were—reveals the inner axonal and dendritic tetherings, drawn in a fanciful way, which conduct electrical impulses to coordinate response and sensation. Also depicted is an adjacent lymphatic chain, opened as well, which serves as the body’s peripheral filtration system, whose flowery cells suck out the toxins we ingest, breathe, and are immersed in. A lone vein completes the portrayal. This assignment has made me appreciate once again the beauty of a higher-celled organism.

—Todd Wider, plastic surgeon

• • •

This object is used in food preparation in Malaysia. The palm milk is allowed to partially ferment in one section, and then the devices in the subsequent sections are used to separate the “wine” from the palm “meat.” The “meat” is allowed to further harden in the final tube and can then be extracted and used as a food source for long journeys and fishing expeditions. The “meat,” a good source of vitamin D and calcium, is also invaluable during typhoon months when harvesting is impossible.

The importance of such devices to the cycle of fishing and exploration has imbued them with additional layers of meaning and significance, and they are often used in ceremonies related to upcoming voyages. Similarly, a useless miniature replica of this device is used in private homes as a fertility symbol. This replica is made out of acacia wood, which has a slightly aphrodisiac quality when placed on the tongue. The connection is therefore more than just symbolic.

—David Byrne, musician and artist

Author of several anthropological classics based on his fieldwork, including Stuck in Song: Notes from Inside the Ecuadorian Sembla Ring (1974), Nib Westingford is now curator of Musical Weaponry at the Moiré Institute in Zurich.

Todd Wider is a practicing plastic surgeon in New York, specializing in craniofacial anomalies and cancer reconstruction. He is currently obsessed with medieval armor, perhaps as a metaphor for romantic attachment in the modern age.

David Byrne is an artist and musician who lives in NY. He was born in Scotland and grew up in suburban Baltimore. His most recent project is a book and DVD that documents his investigations into the use of Powerpoint as an artistic medium.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.