Triskelion

The migrations of a symbol

Sasha Archibald

The three-pronged rotating disk pictured on this vomit bag is a stylized version of the triskelion, an ancient symbol with a long history akin in breadth, if not emotional resonance, to the swastika. The Manx Airlines logo is only one of many adaptations of the emblem, whose history is commonly said to have begun in Asia Minor, although versions of the symbol have been found in ancient Sanskrit, the rock engravings of Hopi Indians in North America, and Norse mythology. Regarded as having a meaning identical to that of the swastika—emblematic of the sun’s movement through the heavens and, hence, of good fortune and prosperity—the triskelion is nonetheless slightly more curious, with its trinity of figurative legs. The symbol is presumed to have begun as a pictograph of the sun whose curved rays were anthropomorphized, perhaps in reference to the deities who personified the sun.

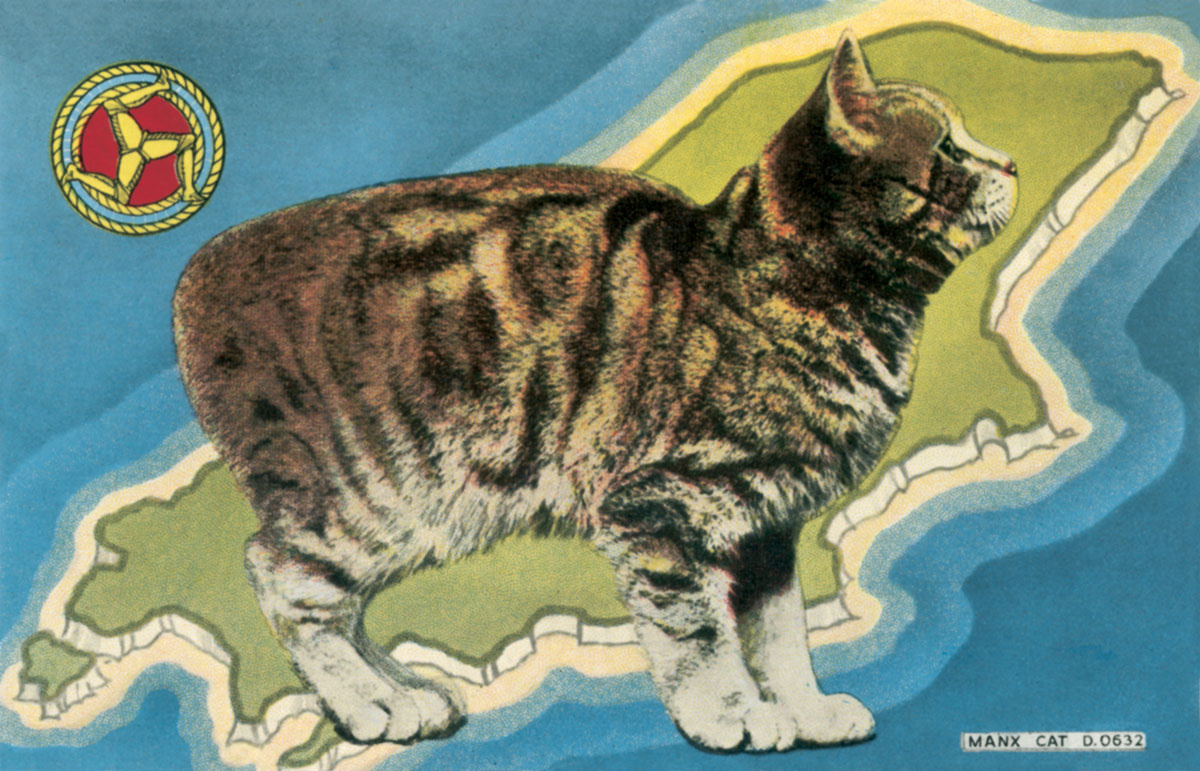

The symbol becomes associated as early as the sixth century BC with Sicily, then a Greek colony, purportedly because of the island’s three promontories. It remains the country’s official emblem. It is also the proud symbol of the Manx people of the Isle of Man, who seem to have inadvertently inherited it from the Sicilians via a long chain of royal marriage and conquest. The triskelion makes its first appearance on the Isle of Man on the Manx Sword of State in 1266, the year in which the Normans ceded the island to Alexander III of Scotland. How Alexander III became acquainted with the Sicilian triskelion is a somewhat convoluted story. Historian John Newton postulates that the migration of the symbol began with Alexander III’s marriage to Margaret, a daughter of Henry III.[1] Margaret’s sister, Isabella, married the Norman king of Sicily, Frederick III, but bore him no male heir. When Frederick died and his illegitimate son took the regency, Pope Innocent IV solicited Henry III’s assistance in organizing a coup against the son. In exchange for his help, Henry demanded that Sicilian rule be awarded to his child son (Margaret’s younger brother), Prince Edmund. The Pope agreed to Henry’s terms. Alexander III and Margaret apparently visited England in 1254, a visit that coincided with the extravagant celebrations honoring Prince Edmund’s new title—celebrations that would have undoubtedly venerated the Sicilian symbol. Alexander, apparently impressed by the emblem, recycled it for the Isle of Man when he was ceded the territory twelve years later.

Manx citizens, however, seem to prefer an official history of the symbol that reaches back to ancient Norse, not Scottish influence; in fact, their unofficial motto for the symbol jeers: “The Arms of Man are three legs: One kneels to England, another kicks at Scotland and the third spurns Ireland!” Norse mythology relates the symbol to the Celtic triplicity in unity—the wave of the sea, the breath of the wind, and the flame of the fire form an equilateral triangle around the earth element—and this tripartite structure is also apparent in the trident of Mannanan, the ancient sea-god whose home was the Isle of Man and for whom the island is named. The Isle of Man’s triskelion pointedly turns to the right, following the movement of traditional Breton dances and processions (a leftward-turning symbol would imply hostility) and is encircled by a gold ring emblazoned with the text “Wheresoever you throw it, it will stand.”

During World War II, the symbol was associated with a different maxim; soldiers of the 23rd Special Troops, or the “Ghost Army,” designed their insignia by combining the triskelion with three bolts of lightning and the unconventional motto, “Deceive to Defeat.” A troop of soldiers with art and design backgrounds who specialized in deception-based warfare, the Ghost Army created innovative camouflage techniques, used sound recordings of soldier activity to disorient or mislead the opposition, and fabricated inflatable decoys. The Ghost Army’s existence remained classified information until 1995; their insignia of legs without faces, unauthorized by the Army and only secretly circulated among members of the troupe, aptly conveys the regiment’s covert operations.

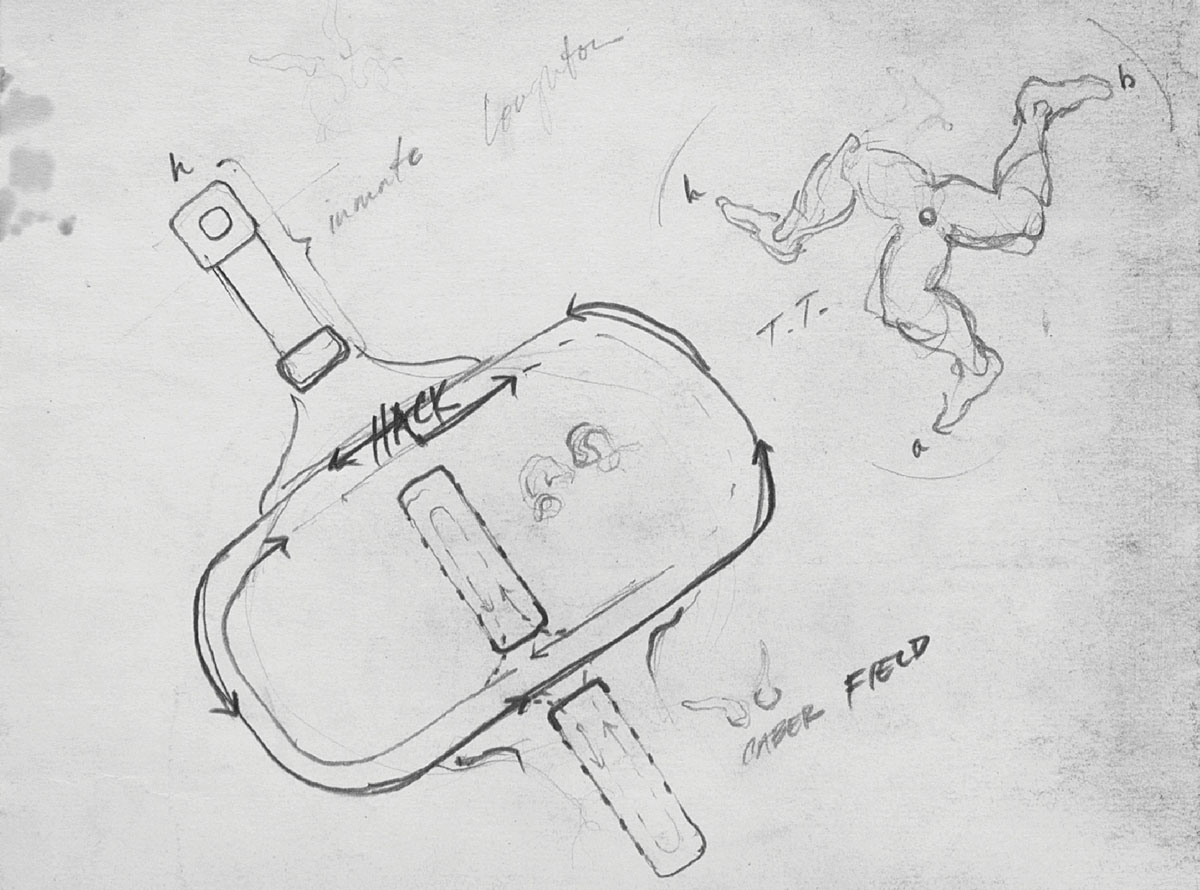

The triskelion might also be recognized as the central visual motif of Matthew Barney’s Cremaster 4 (1994), which takes place on the Isle of Man and richly alludes to the island’s folklore and mythology. In the film, three teams, the Ascending Hacks, the Descending Hacks, and the Loughton Candidate, a satyr wearing a suit, compete in a race that alludes to the Isle of Man’s annual Tourist Trophy motorbike races. The triskelion is the racers’ emblem, emblazoned on motorcycle sidecars and helmets, but also provides the shape of the race itself. The teams furiously travel in three arcs—one to the left, one to the right, while the Loughton Candidate burrows downward through the earth—towards their finish line: the central axis of the triskelion’s spinning legs and point of fusion, collision, and consummation.

- John Newton, “The Armorial Bearings on the Isle of Man,” Proceedings of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Liverpool, no. 39 (1885), p. 207.

Sasha Archibald is an associate editor of Cabinet.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.