Phases of Life 1: The Artificial Foster-Mother

The birth of the incubator

Samantha Vincenty

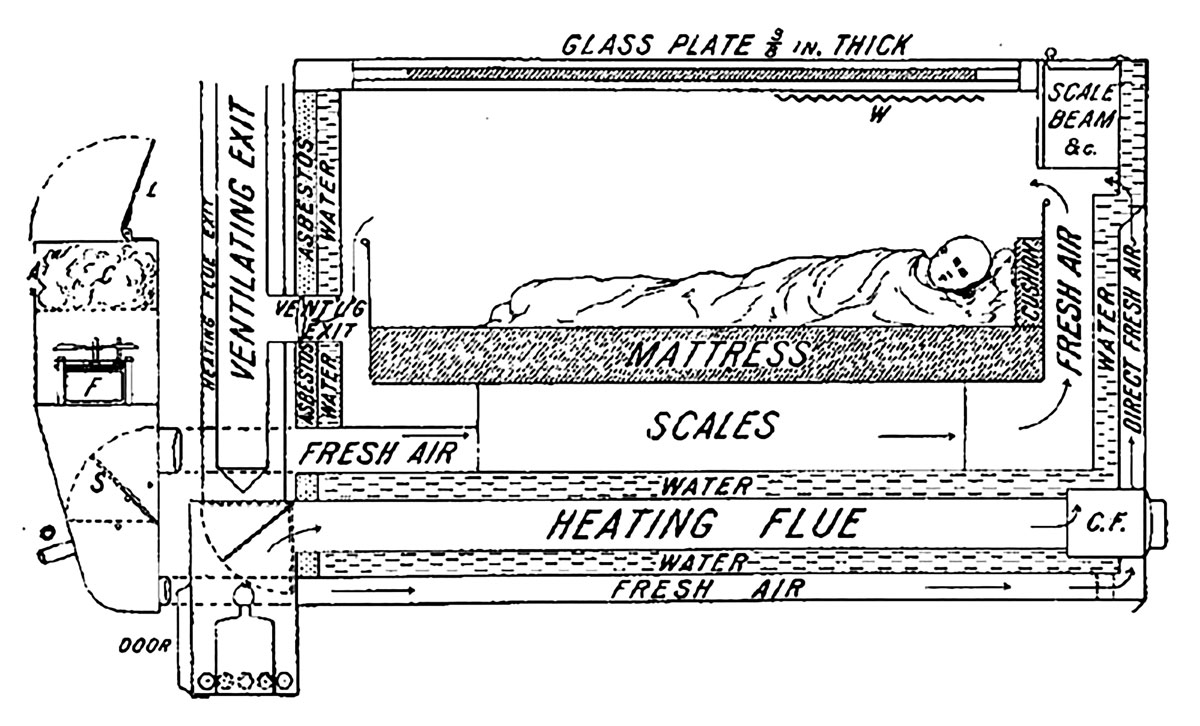

In 1878, an obstetrician at the Paris Maternité named Etienne Tarnier visited the poultry incubation house at the Paris Zoo and forever changed the course of what would come to be known as neonatology. Spurred by what he considered a fatalistic consensus within medicine that prematurity was a hopeless condition, Tarnier commissioned the zoo director to build the first couveuse, or incubator, for human children.[1] There had been several other means of treating premature infants in this period—such as placing them in warming tubs that provided heat from hot water encased between its double steel walls—but Tarnier’s invention provided the unique benefit of a glass enclosure, ideal for both heat retention and optimal observation. Like their predecessors in the hatchery, multiple infants were placed in this first model; after several more revisions to its design and heating methods, each newborn enjoyed privately heated containers.

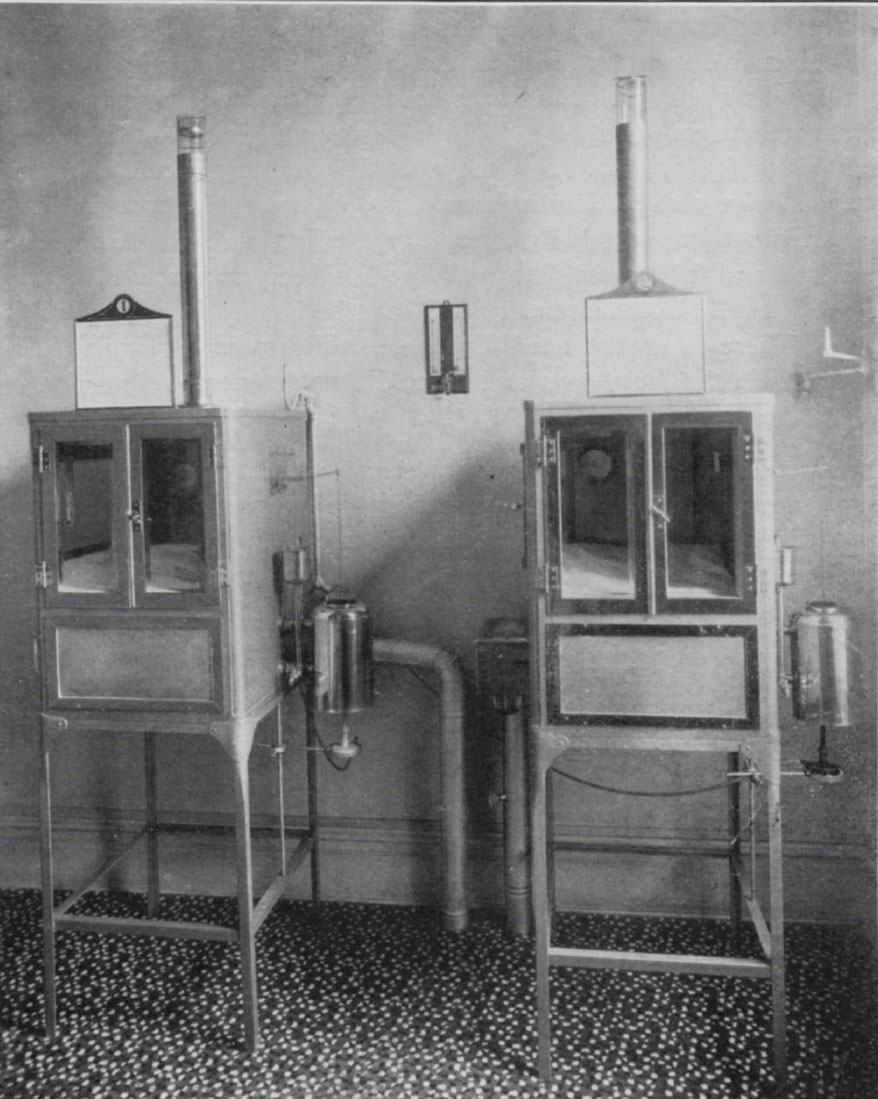

The exhibition of the incubator lay very close to its roots as a zoo exhibit. In 1888, another French doctor, Alexander Lion, recognized the visually compelling power of babies-under-glass. Lion had developed the first commercially available incubator, revolutionary in its regulated heating system and its portability. His machine’s ability to function independent of a hospital setting allowed Lion to establish a storefront maternity ward in Nice. In order to finance his charity and garner the attention of both the public and the medical community, Lion threw open the storefront’s doors and began charging admission to see the “babies just big enough to put in your pocket.”[2] By 1896, four more storefront incubator institutes had opened in France.

Promoting the technology abroad seemed like the next logical step. This would soon be accomplished at world’s fairs and international expositions, which were at the height of their popularity. At the 1901 Pan-American in Buffalo, President McKinley proclaimed them “the timekeepers of progress.... They stimulate the energy, enterprise and intellect of the people and quicken human genius”[3]—unfortunately for McKinley, this Expo was to be his last glimpse of “progress,” as he was assassinated the day after making these remarks. A Paris Maternité alumnus named Martin Couney had better luck than McKinley when he presented his first incubator baby sideshow at the 1896 Berlin Exposition, which featured six newborns from the Berlin Charité hospital. Although the Charité’s doctors believed that the infants were terminal, all six of them survived—and, within two months, Couney’s Kinderbrutanstalt (“child hatchery”) had attracted over 100,000 visitors. After a second show in London—which featured Parisian infants, since British hospitals refused to participate in what they perceived to be an exploitative spectacle—Couney brought his exhibit to the US.

Propped up to face the audience and periodically fed by wet-nurses, the incubated “performers” delighted crowds at the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition, the 1901 Buffalo Pan-American, and the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Although Couney’s sideshows spawned several imitators— Barnum and Bailey offered their own version—the longest running show was Couney’s Premature Baby Incubators building in Coney Island, which opened in 1903 and showcased underdeveloped infants (including, for a brief time, Couney’s own daughter) for almost 40 years. According to a 1939 New Yorker profile, Couney kept careful watch over the diets of his wet-nurses and the behavior of his hired guides, many of whom were actors, to ensure that they stuck to the sober script he had written for them, as they had the tendency to pepper the lectures with “smart-aleck wisecracks.”[4] The sideshows drew little criticism despite the fact that it was selling peeks at children—many of whom were struggling with respiratory ailments, a leading cause of death among preemies—right on the Midway, or in the case of Coney Island’s Dreamland park, alongside Lilliputia, the midget community, and Hell Gate, the thrill ride that started the infamous Dreamland fire. Aside from an initial visit from the Brooklyn Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children and a handful of negative editorials, the shows were largely regarded with reverence. As historian Jeffrey P. Baker has written, “Even the Barnum and Bailey show was described in sober and scientific terms by an American medical journal.”[5]

The 1939 World’s Fair featured the last touring incubator baby sideshow. Since the technology had become mainstream, the Coney Island building ended its nearly 40-year run shortly thereafter. The incubator sideshows offered a nascent form of edutainment while creatively funding an apparatus that boasted a very high survival rate: about 7,500 out of 8000 babies “graduated” from the Coney Island sideshow; at the 1939 World’s Fair, the American Medical Association reported that 86 of the 96 infants exhibited survived.[6] Dr. Couney will not be remembered for innovations in neonatology, but his shows catalyzed a new era in childbirth and neonatal medicine. The advent of the incubator came at a time when childbirth was already in the midst of moving from the home to the hospital; maternity wards were no longer mainly occupied by poor and unmarried women. The incubator was a whole new venue for caregiving, mediated by medicine and entirely divorced from the mother if necessary. The emerging evidence that science could indeed work miracles, presented in the guise of entertainment, may have allayed the collective anxieties that attended such uncharted technological territory and distracted onlookers from the cultural tug-of-war between obstetrics and home birthing.

- Jeffrey P. Baker, The Machine in the Nursery (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 1996), p. 26.

- Smith. Strand Magazine (London) 12:770–776, 1896. See www.neonatology.org/classics/smith/smith.html.

- Baker, The Machine in the Nursery, p. 93.

- A. J. Liebling. “Patron of the Preemies,” The New Yorker, 3 June 1939.

- Baker, p. 92.

- See www.neonatology.org/classics/silverman/silverman1.html.

Samantha Vicenty is a crossword editor and former research assistant for Cabinet. She lives in Brooklyn.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.