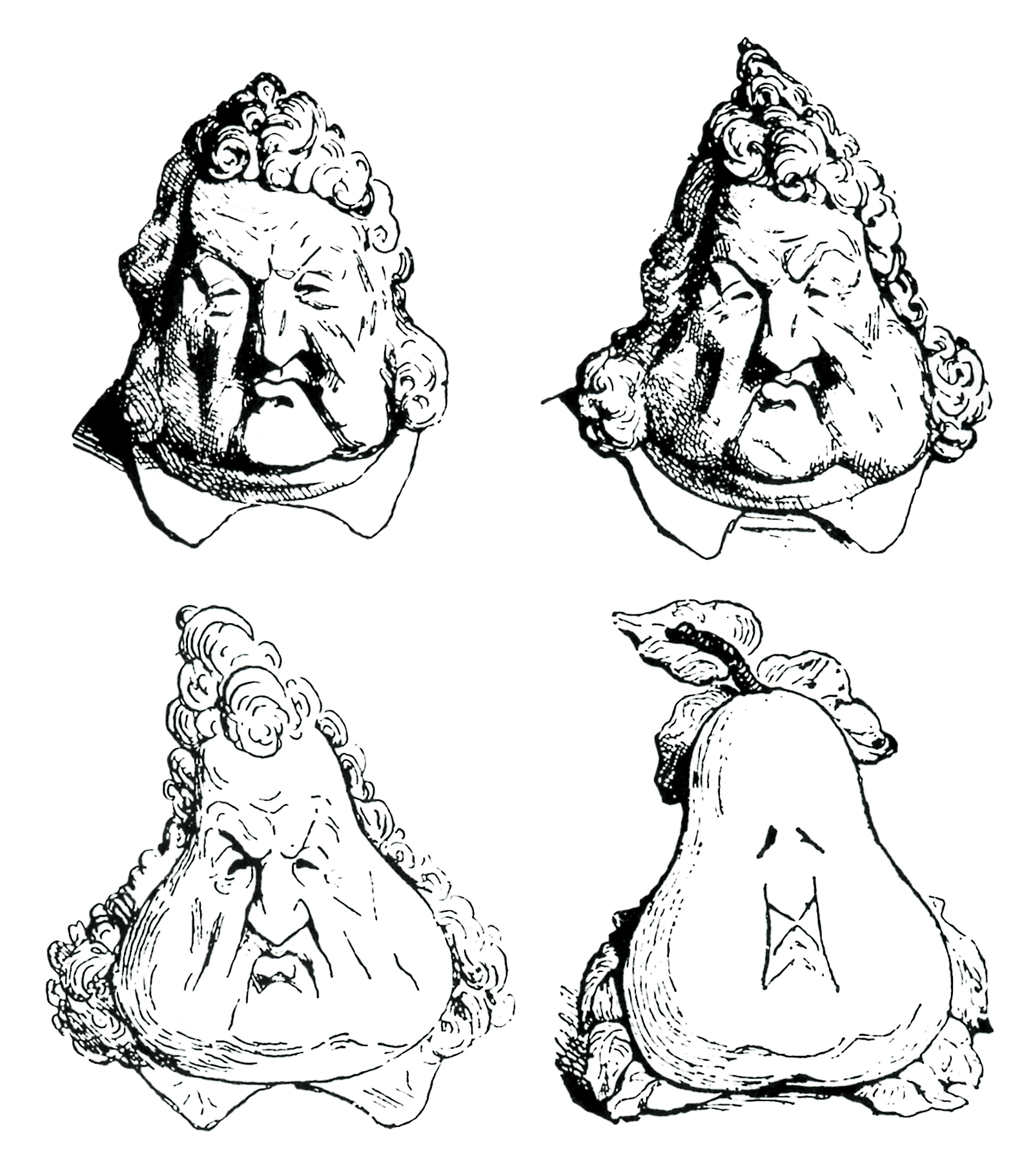

Wide at the Bottom, Narrow at the Top

King Louis-Philippe and the pear

Sasha Archibald

In the wake of new press freedoms won by the July Revolution of 1830, France’s King Louis-Philippe found himself just as popular a target of caricature as his despised predecessor, Charles X. Accordingly, the support of the “Citizen King” for free expression quickly cooled. Between November 1830 and April 1831, a period described in detail in Robert Justin Goldstein’s Censorship of Political Caricature in Nineteenth-Century France, no less than four press laws were passed expressly to limit the publication of images. The primary target of these laws was La Caricature, a tabloid-style weekly founded by twenty-eight-year-old Charles Philipon in November 1830. Philipon’s extraordinary penchant for caricature was outdone only by his zealous commitment to indicting the King. As he goaded the talents of such greats as Daumier, Grandville, and Traviès toward forwarding his cause, Philipon endured a steady barrage of harassment, lawsuits, fines, seizures, and raids, as well as multiple imprisonments. But even prison could not stop him: Philipon directed La Caricature and even launched a new caricature journal, the daily Le Charivari, from behind bars.

The most caustic weapon in La Caricature’s imagistic arsenal was a figure suggesting the ostensible resemblance of King Louis-Philippe’s face to a pear. Prosecuted in May 1831 for publishing two drawings in La Caricature that depicted men who looked like the King, Philipon’s defense ran that if all drawings resembling the King were to be censored, artists would have little left to draw. The government certainly couldn’t censor everything wide at the bottom and narrow at the top, Philipon continued, and to prove his point, he quickly sketched the king’s transformation into a plump pear. Immediately following his widely publicized acquittal, the pear drawings appeared in La Caricature. The likeness resonated with the people of France, and the symbol took off. Pears decorated the walls and buildings of Paris; caricaturists churned out drawings of pears in compromising positions; and common parlance began to denote La Caricature as The Pear. Stendhal’s Lucien Leuwen, Hugo’s Les Miserables, and the memoirs of Thackeray, Heinrich Heine, and Baudelaire all refer to the fruity representations ubiquitous in Paris between 1830 and 1835; an entire book of puns on the theme, Physiology of the Pear, was published in 1832. La Caricature followed the first drawings with several more: The allegorical Liberty constrained by a pear-shaped ball and chain; the king stooping to help a child draw a pear on a city wall; pear trees watered with blood; and pear-shaped arrangements of type. In 1833, Philipon published a particularly incendiary drawing depicting a monument in the shape of a pear placed on the site of Louis XVI’s guillotine death. In the ensuing court trial, the prosecution argued that the drawing constituted “a provocation to murder.” To this Philipon replied, “It would be at most a provocation to make marmalade.”

Sasha Archibald is associate editor of Cabinet and a Helena Rubenstein Curatorial Fellow in the Whitney Museum Independent Study Program.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.