Leftovers / The London Necropolis Railway

A one-way ticket to the Brookwood Cemetery

John M. Clarke

“Leftovers” is a column that investigates the cultural significance of detritus.

Brookwood Cemetery, near Woking in Surrey, is the largest burial ground in Britain. It was built by the London Necropolis & National Mausoleum Company (LNC), established by a special Act of Parliament in 1852, as a one-stop solution to the problem of burying a burgeoning London’s dead. The cemetery opened two years later; at 500 acres, it was then the largest burial ground in the world.

Brookwood was over twenty-five miles from central London and its most unusual distinguishing feature was that it was served by its own private railway. The funeral trains carrying mourners and cadavers left from a station at 121 Westminster Bridge Road, just outside the Waterloo terminus. This unique station (designed by the LNC’s general manager, Cyril B. Tubbs) contained funerary workshops, mortuaries, and a private chapel of rest. It was used by the railway funeral service until 16 April 1941, when it was destroyed in the worst night of the Blitz by a German bomb. It was never rebuilt after World War II.

The funeral trains originally ran once a day (64,000 people were buried at Brookwood in its first twenty years), although by the 1930s it was unusual for the trains to operate more than twice a week. They left the private station at Westminster Bridge Road and joined the London & South Western Railway’s main line for the hour-long journey, and then reversed into the cemetery grounds at Brookwood. There were two stations to greet them there: North Station, which served Nonconformists, and South Station, for Anglicans, who occupied by far the larger part of the cemetery. Each station had its own licensed bar.

Death is meant to be the great leveler, but the funeral trains preserved class divisions and distinctions along with religious ones. You traveled strictly according to the funeral package you paid for. First Class mourners would travel in the most comfortable carriages on the journey to Brookwood, whereas Third Class was invariably used for paupers who were buried at parish expense.

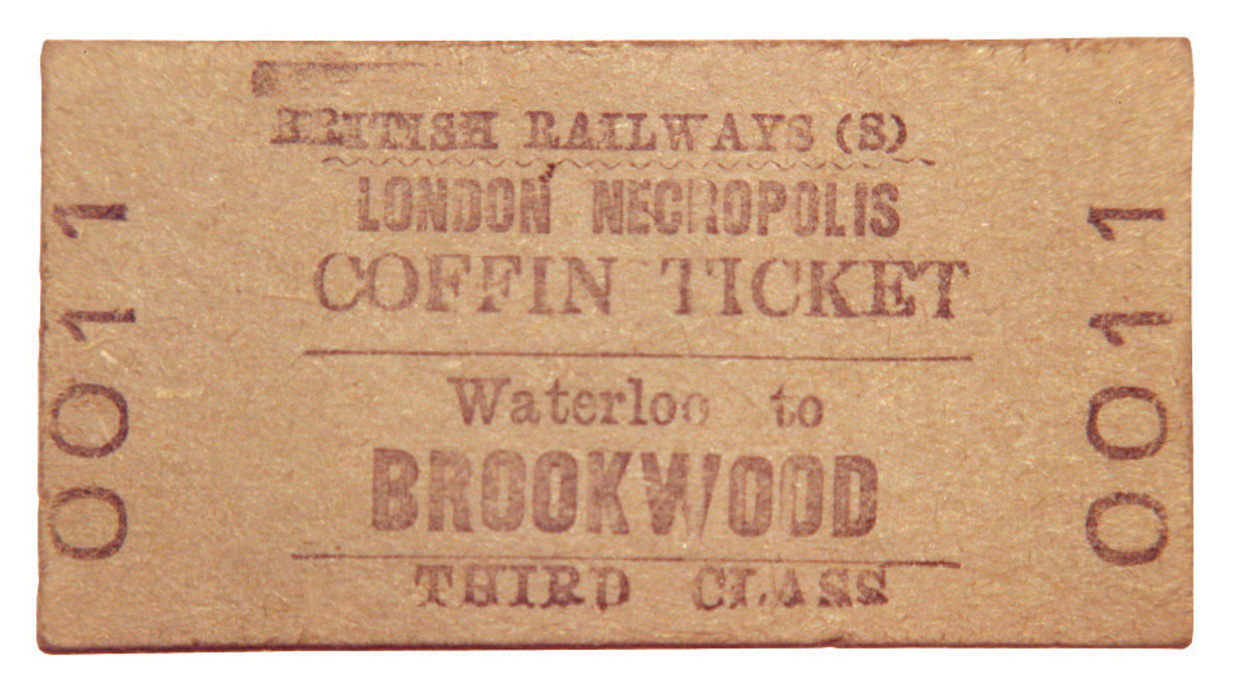

These distinctions were also applied to the deceased since First, Second, and Third Class coffin tickets (one-way, of course!) were issued for use on the trains. Not that they would have noticed the difference—the main method of distinguishing between the classes of the dead appears to have been the amount of decoration on the doors of the special hearse carriages used on these trains.

Sir Henry Morton Stanley (1841–1904) was perhaps the most famous passenger-corpse to use the Necropolis line. A famous journalist and explorer, best remembered for finding Dr. Livingstone at Ujiji (where, according to legend, he introduced himself by saying, “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?”), Stanley was granted a state funeral in Westminster Abbey, just like Livingstone. After the pomp and ceremony of the service, his horse-drawn hearse processed through London from Westminster to Waterloo, where his coffin was put aboard the funeral train. However, Stanley was not in fact buried at Brookwood—another hearse was on standby to take him to the graveyard at Pirbright Church, near his family home in Surrey, just over a mile away.

Today, only a few reminders of this extraordinarily morbid railway service remain. In London, the entrance building to the private station at 121 Westminster Bridge Road survives; at Brookwood, both stations were destroyed in the 1960s and early 1970s (a monastery, occupied by the St. Edward Brotherhood, has been built where South Station used to be). However, there are still a few clues to its history. The track bed of the railway can be followed through the cemetery grounds by a careful observer, where the two platforms to which they lead lie in ruins.

John M. Clarke has been exploring Brookwood Cemetery since 1976 and conducting guided walks around the cemetery since 1990. He is the author of three books on the Brookwood Cemetery and Necropolis Railroad, including the recent London’s Necropolis: A Guide to Brookwood Cemetery (Sutton Publishing, 2004), and is librarian of the Institute of Child Health and Great Ormond Street Hospital.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.