Object Lesson / Transitional Object

The cabinet of Baron de la Mosson

Celeste Olalquiaga

“Object Lesson,” a column by Celeste Olalquiaga, reads culture against the grain to identify the striking illustrations of a historical process of principle.

It is a modern convention to see culture as something alive and changing, yet by the time a trend is actually perceived it has often been dead for quite a while, the myriad artifacts it leaves behind acting as so many witnesses in, and for, its wake. The European curiosity cabinets of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries are among the best testimonials to these transitional moments of which culture is almost entirely made.

Caught between two modes of thinking and living—one traditional and theologically-based; the other modern and materially oriented—as well as registering a deeply changing relation to nature, the history of these monuments to human inquisitiveness spans almost two centuries of transformation, a period considered “illuminating” for its rational, systematic attempt at understanding how the world works. Curiosity cabinets were doubly residual: largely populated by the most “morte” of all natures (dried, stuffed, and bottled animals, plus all sorts of organic leftovers), they were also the poor offspring of the fabulous Wunderkammern, or wonder chambers, of the Renaissance, those immense collections of “rare” objects, where the natural and the artificial—products of “divine” and human craft, respectively—lived side-by-side as objects of amazement.

Unlike the Wunderkammern, where the elements of what we now call natural history were mainly objects of puzzlement and awe—not to speak of décor—the curiosity cabinets of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries mark the onset of a desire to grasp and control the mystery which made of nature such an enthralling realm. Once Wunderkammern began to lose their allure in the face of, among other things, a colonial expansion that made their treasures far more familiar and available than befits a bona fide object of wonder, the curiosity cabinet became the privileged form of exhibiting such goods.

This shift triggered a corresponding change in modes of display: moving out of the royal palaces—and coffers—that had made the fantastic scenarios of the Wunderkammern possible, naturalia began to be separated from artificialia (coins, instruments, and artworks such as paintings, sculptures, etc.), and organized by kind (shells, fossils, insects, etc.), enabling the typologies and classifications that established the basis for scientific thought. The enormous, unprecedented accumulations of both naturalia and artificialia contained in the Wunderkammern were then relocated from palaces and churches into the less glamorous, if equally prestigious, châteaux and mansions of the nobility. Further reduced and scattered, they continued this journey into places as seemingly disparate as the bourgeois salons of the nineteenth century and their institutional peers, that is to say, museums, of which the Wunderkammern and curiosity cabinets are the legitimate precursors. Quite literally, then, these collections went from riches to rags.

The change in spatial disposition that characterized the earlier part of this displacement was the first manifestation of the shift from the collections’ performative character into a more analytical mode of presentation. As they became the subject of proto-scientific inquiry, the collections of organic remains, which had hung theatrically from ceilings and walls, producing what had been considered a macrocosmic effect, began to be methodically arranged and stored on shelves and in drawers. In so doing, they sacrificed the immediacy of exhibition for the layered complexities of inquiry, a mode that suspects things of concealing essential truths and even representing something other than their simple selves. Natural history was no longer a matter of surface and exteriority, and therefore of mere aesthetic arrangement and disposition, but rather one of depth and interiority in the empirical sense. Admirative joy gave way to autopsic glee.

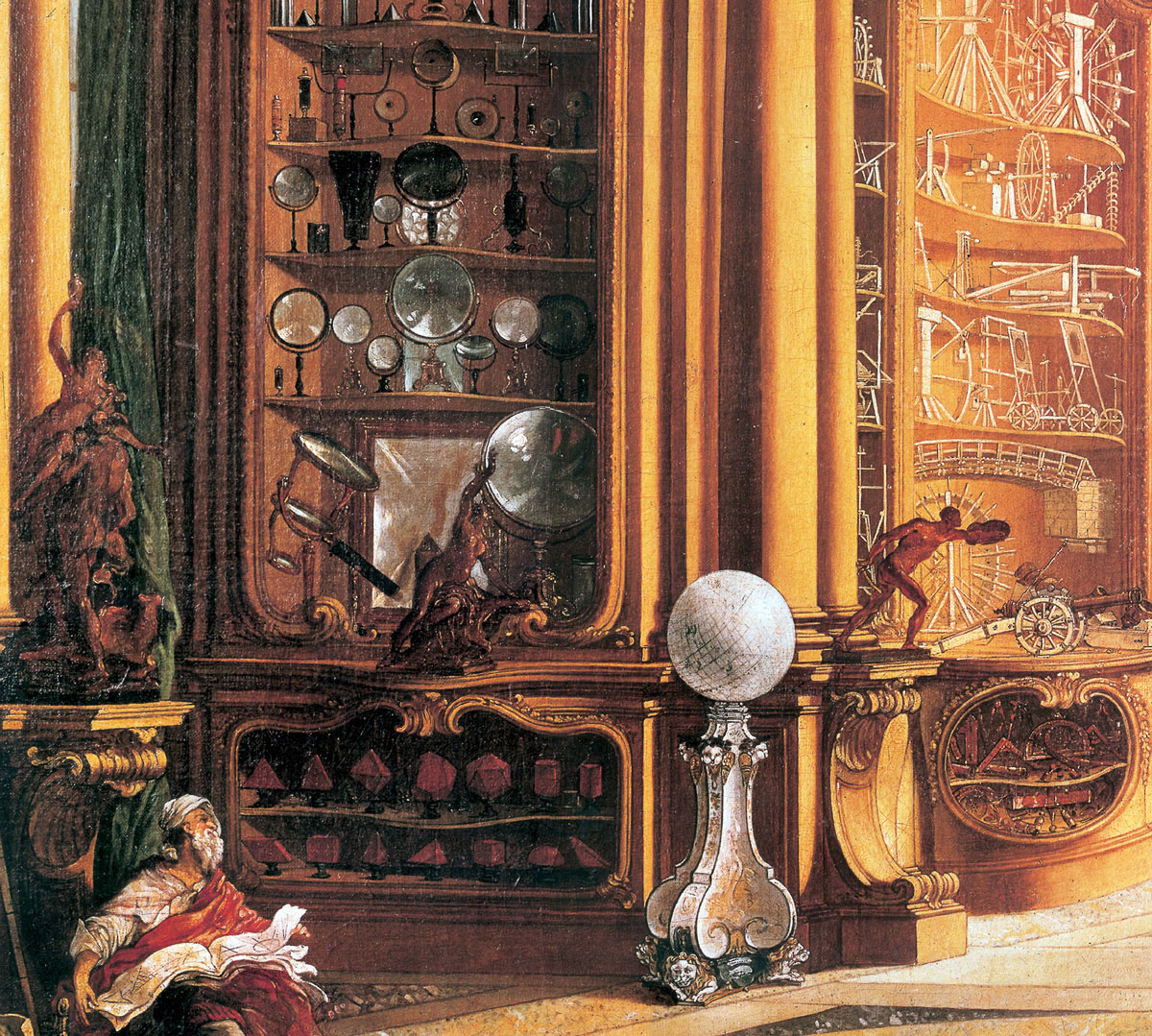

This particular transition from wonder to knowledge is recorded in a curiosity cabinet whose singularity is surpassed only by its beauty. Hidden away in the endless folds of Paris’s Jardin des Plantes, the Cabinet Bonnier de la Mosson stands as a unique manifestation of the intersection between aesthetics and science. Dating back to 1735, this luxurious cabinet, amassed and exhibited thanks to a family fortune based on the procurement of regional taxes, has the rare quality of combining the atmospheric mise-en-scène of the preceding Wunderkammern with the organizational intent of the later cabinets, producing an original blend of system and fantasy. Considered by many the richest and most imaginative French cabinet of the early eighteenth century, this curiosity cabinet was housed in the hôtel particulier, as the city residences of aristocrats and royalty were known, of Joseph Bonnier de la Mosson (1702–1744), located in the now extinct rue des Dominiques.

A young and rich heir as eccentric as he was talented, le Baron de la Mosson belonged to that privileged class that can afford to indulge in the pleasures of beauty and freedom without accountability, at least during their lifetime (what happens afterwards being quite a different story). Scandalous and nonchalant, this dandyesque collector did as he pleased both privately and publicly, setting up his most famous mistress, the opera singer “La Petitpas,” in his luxurious Hôtel du Lude. Having changed hands a few times before housing part of the Bonnier patrimony (the rest was in the Château de la Mosson, near Montpellier), this hôtel had on its first floor a row of seven connected rooms overlooking an expansive garden, an arrangement that enabled the Baron to set his cabinet like a thematic gallery.

Each of the three largest rooms was dedicated to a different component of the cabinet; the Library, which contained all the “musts” of a collector worthy of the name; the Cabinet of Mechanics and Physics, the earliest and, for some, the most outstanding because of its scientific instruments; and the Second Cabinet of Natural History, boasting a magnificent array of preserved animals. It is this last section, and specifically its furniture, that the naturalist Buffon (author of the voluminous Histoire Naturelle, considered the first modern encyclopedic compendium) purchased for the equivalent of $45,000 at the sale of the Cabinet Bonnier in 1745, with the purpose of integrating it into what was then known as the Cabinet du Roi and after the French Revolution became the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle. The remaining, smaller four rooms were dedicated to the Cabinet of Chemistry or Laboratory; the Cabinet of Pharmaceutics or Apothecary; the Cabinet of Tools; and the First Cabinet of Natural History (which Bonnier consolidated with the droguerie in 1740), containing hundreds of fish, reptiles, plants, and even human fetuses, in jars. Finally, discreetly exhibited in a small corridor off this latter room were several anatomical “curiosities,” such as a black man’s skull—dried skin and all—as well as models of male and female reproductive organs in colored wax.

In itself, the great variety of the cabinet constituted an event: conceived as a proto-scientific endeavor, Bonnier started by collecting mechanical and laboratory instruments, to which naturalia, all sorts of physical and chemical oddities including virginal milk and red gold powder, and even automatons were added, making of his cabinet the equivalent of several in one. Yet while the collection’s quantitative richness enabled each particular cabinet to occupy the wall of an entire room, what was most impressive was its quality, the wealthy amateur, as Bonnier was known, having even traveled to Holland twice to acquire items directly, instead of through his favorite Pont Neuf merchant, Edme-François Gersaint (1694–1750). This famous art dealer, the first to conduct a natural history sale in Paris in 1736, was charged with the inventory and auction of the collection after Bonnier’s premature death, thus being placed in the peculiar position of helping to assemble and then dismantle the collection in less than ten years.

Beyond the collection, what stood out the most was the furniture in which it was exhibited—the cabinets were made of a precious oak, and some of the display cases lacquered and adorned with organic motifs. This décor reached a baroque apotheosis in the Second Cabinet, whose glass doors were surrounded by elaborate fauna and flora carvings, as well as items drawn from the collection itself, such as animal horns and heads (daintily known in French as massacres), which were affixed, along with corals and shells, to the armoires. The delirious complexity of this “seductive sight” not only matched but even accentuated that of the fascinating objects contained within.

It is the unique mise-en-scène of the Second Cabinet of Natural History’s wooden skeleton, so to speak, which constitutes the major interest of the Cabinet Bonnier today. By taking the collections off the walls and ceilings and enclosing them instead within the confines of shelves and drawers, cabinets in general acted as mediators between objects and spectators, adding a layer of concealment and distance to what had until then been presented as an integral part of the viewer’s universe, not something that required differentiation. Furthermore, this kind of arrangement and composition represented a fundamental shift from the Wunderkammern’s three-dimensional environment to a two-dimensional plane: whereas in the former, visitors entered a room where they were literally surrounded by “wonders” that made their heads turn in every which way, in the latter they stood facing the cabinets, their frontality signaling that being integral to the universe had become second to looking at it.

Yet, by reproducing the antics of macrocosmic desire in an alignment that responds more to the notion of linear continuity than to that of circular containment (thus sitting on the threshold of modernity), the Cabinet Bonnier manages to transfer this theatrical atmosphere to a new visual register in which, rather than simultaneously perceived, display is read like the pages of an open book. This impression is enhanced by the Cabinet’s disposition as a horizontal C, with its three central armoires facing the windows, and a lateral armoire on each side. Consequently, while the Cabinet Bonnier as a whole is usually lauded for its proto-encyclopedic virtues (the Cabinet predates Diderot’s Encyclopédie, compiled between 1751 and 1780, but is clearly of the same spirit, given its thematic specialization and range), what strikes a contemporary viewer most about the Second Cabinet of Natural History is its capacity to thread multiple scenarios in an atmospheric continuum, weaving through the different armoires and shelves in such a way that the gaze does not stop at any one element, but rather seeks to take in the whole—shelf by shelf, item by item—with the same voracity with which we devour the phrases of an enthralling text.

Here, the eye acts like a camera traveling over the treasurescape offered by the cabinet, a sort of visual caress that elicits the ambiguous joy of touching the cabinet and its objects, yet at a distance. For unlike the preceding Wunderkammern, where the elements of natural history remained within tactile grasp, the moment the collections’ format is reduced and stacked, the peculiar concealment of bidimensionality is substituted for panoramic display. Depth, rather than being conveyed by traditional perspective, is implied by the symmetry of arrangements whose apparent simplicity is in fact redefining the relationship between the internal and the external. This particular mode of display unwittingly lays the ground for the fully-developed scientific vision that, abandoning all interest in surfaces, will study natural history from the outside in.

At the very same time, cabinets began to incorporate an element that was absent in the original Wunderkammern, and which enhances the aura of organic remains while simultaneously keeping them farther out of reach than ever. This element is glass, and perhaps few cabinets exhibit it so magnificently and self-consciously as the Second Cabinet of the Bonnier collection, where wrapped by the coils of wooden serpents, the glass-paneled doors add a luminous layer that, like an artificial frost, transforms natural history into an enchanted scenario. For glass, through its transparency and shine, has the rare virtue of simultaneously animating and distancing the objects it covers, endowing them with both life and death. This is why it was used in the Middle Ages to protect the relics of saints—which were at the very origin of Wunderkammern—and later on to add distinction to all cult objects, from material remains that signaled a mystical relation to nature to those art objects whose status deserved, or simply needed, such veneration.

Glass, the materialization of the aura once ascribed to sacred people and objects, seals a sort of visual pact with the spectator, an exchange treaty whereby the viewer agrees to sacrifice proximity and potential tactility for the pleasure of ocular astonishment. It is as if glass grants spectators the privilege of a visit to a fantastic world whose main force resides precisely in being imaginary. There is no real equivalent to this dimension, and therefore viewers accept the deal, half-knowing that it hinges on the elusiveness of a desire whose fleeting satisfaction is worth the price of a distance both spatial and hierarchical. The gradual introduction of glass as a major actor in cabinets underlines this transition from a theologized nature, felt as close and familiar, to a reified one removed to a second degree. This final remystification of organic remains is ironically also their swan song, preparing their imminent fall into the dissecting hands of science.

The Cabinet Bonnier de la Mosson is a visual transcript of this complex transition from theology to reason, and from touch to vision, that was centuries in the making. The fascination elicited nowadays by its Second Cabinet of Natural History is far from the one the entire cabinet knew during its heyday, when Bonnier proudly showed it to a general public that comprised aristocrats, scientists, and laymen alike, enabling the private to become public long before this practice became current, and profitable. This at a moment when the natural history fever in Paris was so strong that the Cabinet du Roi attracted 1,200 to 1,500 visitors a day, an attendance many museums of natural history would surely envy today. The most brilliant product of one of the largest inheritances of the time (equivalent to almost $2 billion), the Cabinet Bonnier was rapidly sold and disseminated after the eccentric Baron’s sudden and mysterious death at the age of 42, in part to settle his outstanding debt to Louis XV. This amount—some $90 million in taxes collected by Bonnier but never transferred to the crown—represented about five percent of the original Bonnier de la Mosson fortune.

Interestingly enough, Bonnier established his cabinet during roughly the same four years he was conducting his passionate and scandalous affair with La Petitpas, for whom he built a fairy palace in his garden and fought with neighbors and priests alike, much to the general contentment of the gossip circles of the time. Painted by Watteau and Nattier, the inspiration for at least one satirical tract, and chronicled later by the Goncourt brothers, “Gilles”—as the opera girls referred to the erudite collector—was a central character of eighteenth-century Parisian idle society. Once the relationship with La Petitpas dwindled, the now melancholic Baron considered his cabinet finished and commissioned the architect Jean Baptiste Courtonne le Jeune (1711–1781) to execute the drawings that have kept it for the record. Soon after La Petitpas’ death, Bonnier married and died, as if unable to survive the passage from the world of pleasure and fantasy he had created for himself into that of a society for whose morality he cared so little. His cabinet, then, was maybe as much of a transitional object for him as it is for the history it now represents.

Celeste Olalquiaga is the author of Megalopolis: Contemporary Cultural Sensibilities (University of Minnesota Press, 1992) and The Artificial Kingdom: A Treasury of the Kitsch Experience (Pantheon, 1998). She is currently writing a book on petrification. See www.celesteolalquiaga.com for more information.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.