Re-Use Value

Stock photography and the future of the past

Jenny Tobias

Consider this image. It’s clearly a turn-of-the-century studio portrait, but what else is it? To a stock photography agency, it could be an umbrella ad, a calendar illustration, or a costume designer’s reference. To one agency, it’s identified as:

According to the original caption, it is also a Portrait of Otto Bettmann—About 2 Years of Age, With an Umbrella.

Little Otto in his skirts could not have known that he would start collecting images as a teenager, earn a Ph.D. at twenty-five, begin compiling a picture history of civilization while curator of rare books in the Prussian State Art Library in Berlin, flee Nazism to the United States in 1935, and shortly thereafter found the Bettmann Archive, a major purveyor of stock photography. Nor did he know that sixty years after its founding, the Archive would be acquired by Microsoft’s Bill Gates for his Corbis image archive, shipped from lower Manhattan to a climate-controlled Pennsylvania mountain for preservation and digitization, and then redistributed over the Internet, where little Otto can be found today, exactly a century after the photographer snapped the shutter.

Stock photography plays a role in all contemporary media, from print to cinema to television, from the analogue to the digital (including computer games). It appears in news and entertainment media, and in commercial, literary, and scholarly publishing. It’s also intertwined with art photography, because artists both produce and use stock imagery. In the categorizing spirit of the industry, let’s define stock as the commercially motivated creation, collection, organization, and/or dissemination of professional but anonymous or corporatized images. Stock increasingly includes photojournalistic, moving-image, art historical, and fully computer-generated work—and even audio clips. One need only start reading photo credits to discover stock’s pervasiveness. No credit? That’s often stock too, at several removes from its origin. Like émigré Otto.

Pervasive but uncredited—this is also the place of stock in the history of photography. Yet, through its visual power and ubiquity, stock photography has played an important, if unwitting, role in promulgating new assumptions (or anxieties) about media in general and photography in particular. Over the past hundred years, stock’s consumers—we, the media-literate public—have come to terms with concepts that are as fundamental to the stock industry as to theories of the postmodern image. Specifically: photographs have no “essential” meaning or inherent truth; commerce, journalism, and art are deeply interrelated; authorship is fluid; and imagery of the past is integral to image-making in the present and future. Bettmann’s baby picture is a good example. The multiple categories defining his portrait demonstrate stock agencies’ understanding that images carry meaning far beyond the photographer’s intention and any inherent photographic truth. For example, nothing in this image itself denotes Jewish, which, like Whites, functions in the typological list more as a fraught social designation than as a visual cue. To contemporary eyes, moreover, the image could as easily be filed under Girls as Boys, while only in retrospect do the terms Prominent Persons and Archivist apply. German and American, similarly, may account for Bettmann’s émigré experience, but are hardly legible in the image. Yet, oddly, in listing all this detail, no descriptor fixes the picture in its era. To the stock industry, images are timeless because they are mutable.

As Bettmann recounts in his lively memoir Bettmann: The Picture Man, his pictorial history of civilization—which evolved into the Archive—entailed, among other methods of image-capture, the photographic cropping of famous artworks into decontextualized, freely circulating signs. A 1932 catalogue card, for example, shows a detail of Saint Lucas Drawing Madonna (ca. 1450) by Rogier van der Weyden. Under the general heading Writing Material, various subjects are parsed and cross-referenced: Drawing, Hands, Artist, Silverpoint, and Pergament (parchment). Such content-driven categorization would become key to the Archive’s commercial future, as a writer for the magazine P.M. foresaw just months after Bettmann arrived in the US:

This collection has not been made as an art collection. Subject matter is the foremost consideration ... [He] makes it possible to press the painters of old ... into service as illustrators.

In this way, the early business habits of stock agencies anticipated the postmodern understanding that images constitute “floating signs” in which meaning can be determined only in context.

As a product for sale, stock’s context is consumer desire, and the index of this interest is the agency classification system. How do people search for images—that is, how do they locate in the plethora of available goods the particular picture-commodity they wish to buy? A 2001 micro-study in Creative Review, a publication serving the advertising and graphic design industry, reflects the often clumsy process of matching a general idea to a particular representation. In the informal, month-long survey of stock agencies, top search categories included Baby, Business, Computer/s, Family, Flower/s, Internet, Water, Woman/en, and the more specialized science-photo category Human Body. (Oddly, Man was a top search at only one agency, less popular than Money or Dog.) The survey suggests that the search process tends to begin with simple nouns like these, and end with subtle abstractions. For example, Getty customers who searched on their own most often queried People, Business, or Computer, while the most frequent searches mediated by a stock-agency rep were Escapism, Absence, Cut Out, Nobody, Strategy, Afterlife, Role Reversal, and Communication Problems. Because of this unstable relationship between ideas and images, categorizing is the focus of much research and development in the world of stock, and “keyword” is now a verb. Keywording writes the new master narrative.

Master narratives of photography’s history, however, are only now recognizing stock photography. Long marginalized along with that of most commercial photography, the history of stock photography is as fragmented as its images. Still, historians who have tackled the subject seem to agree on four elements central to stock’s development: the professionalization of photography, advertising, and modeling—especially modeling by women—in the late nineteenth century; the popularity of photographic entertainments like the stereoscope; the rise of the picture press in the early twentieth century; and the sheer magnitude of stock itself—the quantities of photographs available for use and reuse.

In the twentieth century, stock emerged as a discrete commercial practice. Of agencies that have been studied, sales records from the H. Armstrong Roberts agency date to 1913, and it published a catalogue in 1920 that is believed to be the first of its kind. The Black Box studio in New York and Photographic Advertising Limited in London were selling stock by the early 1930s, and the Bettmann Archive was founded in late 1935, less than a year before the debut of Life magazine. By mid-century, stock agencies were integral to journalism and advertising. Culver Pictures, prominent through the 1950s, was born of just such a confluence: working at a Philadelphia newspaper in the 1920s, D. Jay Culver repurposed unused publicity photographs, reselling them as photo essays to New York magazines. As television and other non-print media became prominent, successful stock agencies reinvented themselves to suit. Beginning in the late 1980s, intense consolidation resulted in mega-agencies, notably Getty Images, which now commands 70 million visual assets, having acquired major stock archives and similar repositories of audio, film, art, sports, news, and celebrity photography. Its holdings include Time-Life images as well as the major collection of British photojournalism, the Hulton Archive. Whatever the medium, the first century of stock is the history of speculative interrelationships between journalism, art, and commerce, in which a source can be a client, a client can be a source, and sources might be once or twice removed from their original context.

Thus, by the 1980s, Barbara Kruger, Richard Prince, and other media-conscious artists of the “Pictures Generation” had almost a century of journalistic and commercial photography to mine for their investigations of the generic image. Their works questioned notions of originality, as well as the gender and ethnic stereotypes perpetuated by stock photography. And of course, advertising itself soon reincorporated the postmodern lessons of media appropriation and recontextualization. Addressing the interconnectedness of art and commerce, in the early 1990s artist and designer Tibor Kalman edited Colors, an advertisement in the form of a magazine published by the Benetton clothing company. Colors made extensive use of stock, with particular emphasis on recontextualization. Kalman claimed to use photography to show that “you have to learn (and then teach others) to mistrust everything. ... To be responsible, those of us who work in the media have to tell people not to believe in us.”

Arguably, a proportion of media consumers today have learned this lesson precisely because of these powerful deployments of stock photography, resulting in a kind of media-savvy available even to primary school children: a knowing attitude towards the fluidity of fact and fiction, news and entertainment, art and commerce. Of course, such cynicism does not readily translate into immunity from advertising’s influence. Colors stimulated an unusual amount of public debate about photojournalistic manipulation and sensationalism, much of it focused on explicitly altered images (such as Queen Elizabeth Photoshopped with Asian features). Ironically, debate about Colors became a media event in itself, much of it sensationalist: Kalman achieved his goal. For while photojournalism still carries the baggage of objectivity, stock is manipulative by definition. For example, in stock’s copyright-casual early days, rights were often sold to a corporate body, abandoned, ignored, or lost through successive appropriations. Images would also often be further decontextualized through re-captioning, cropping, “ghosting” and “silhouetting,” in which the central image is isolated from its background.

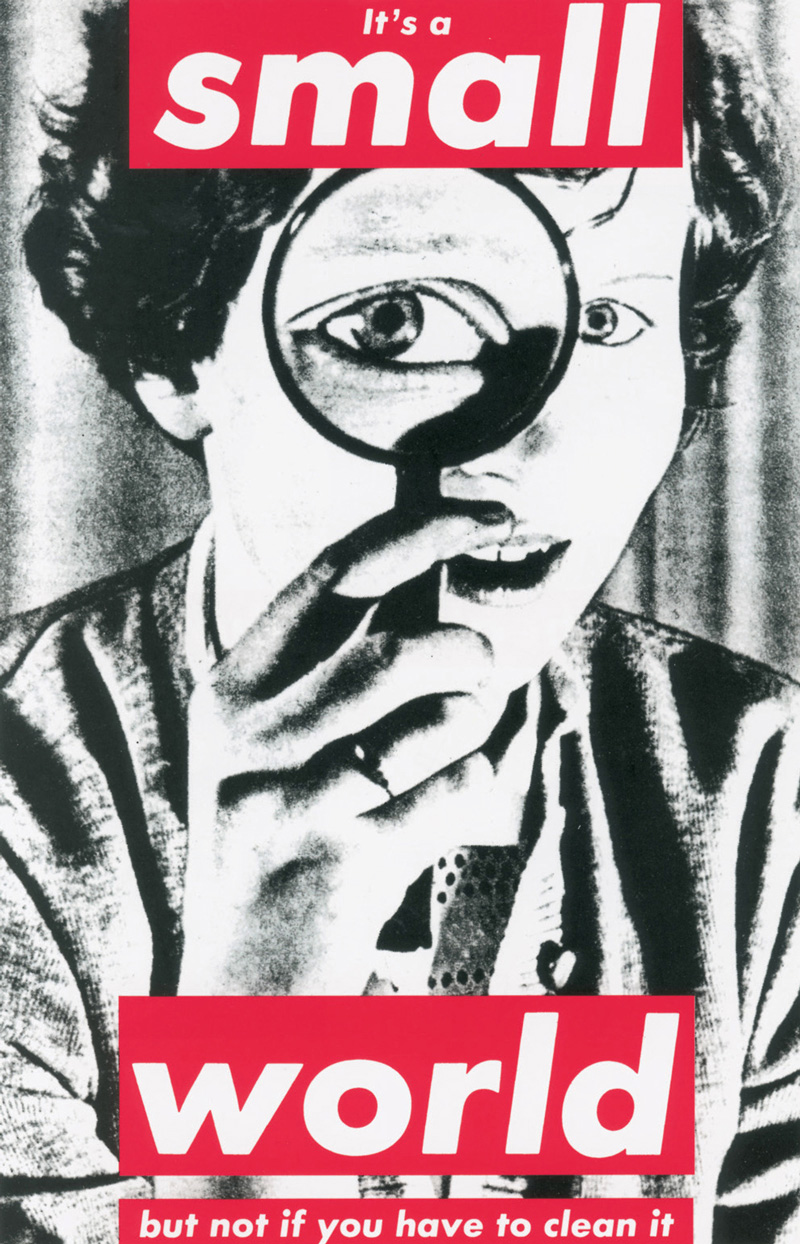

Sometimes, though, the author refuses to give up the ghosting. Consider Barbara Kruger’s 1990 silkscreen Untitled (It’s a Small World But Not If You Have to Clean It). Anyone acquainted with the artist’s work would assume that the photograph is an anonymous image drawn from an advertisement, picture library, or stock agency. Anyone, that is, except for Magnum photographer Thomas Höpker and his subject, Charlotte Dabney, who sued Kruger for appropriating Charlotte, As Seen By Thomas (ca. 1959), charging copyright infringement, “unfair competition,” and violation of Dabney’s civil right to privacy by making her “a public spectacle.”

For Dabney and Höpker, Charlotte, As Seen by Thomas remained the inalienable work of one photographer and one subject. But Charlotte was seen in a slightly different way by the editors of the German photography magazine Foto Prisma, which published it in 1960, and in another by Kruger, who thirty years later appropriated the shot from an unknown source and cropped it into politically charged art. It was then seen by museums as a promotional tool: for Kruger’s traveling retrospective in 1999–2000, the work was manufactured into everything from refrigerator magnets to a five-story billboard. In the end, the suit was thrown out on a significant technicality: copyright law changed—and changed back—at key moments, placing Charlotte in the US public domain between 1988 and 1994.

In this context, authorship is ultimately a function of international copyright law, and authorship plays a much greater role in the stock industry today, in the era of Disney-driven copyright extension. Because rights management can inhibit use (ask any scholar or publisher), the stock industry has responded with lucrative “rights-free” collections. These themed image collections (often pre-silhouetted) are sold once for unlimited use by the buyer.

Yet an equally strong industry trend concerns new claims to authorship and identity, with recognizably “name brand” sources like Tony Stone Images (now owned by Getty) in demand as an alternative to truly generic, anonymous-looking stock. Max Zerrahn’s A woman holding a magnifying glass to her eye (undated) from the stock agency fStop/Veer embraces the snapshot aesthetic, grunge fashion, and quasi-portraiture. Not only is the photographer named; we learn that “Max plays guitar in the Indiepop band Solarscape.”

Works like this not only reappropriate for the commercial market the aesthetics of Nan Goldin and Cindy Sherman, but commodify the “lifestyle” and politics of their images as well. On the other hand, the work represents a new legitimacy for unapologetically “commercial art.” One might even call it Realist Capitalism: the frank embrace of photography’s role in a larger socio-economic system.

The art-stock model also operates in reverse: stock-photo morgues are being reanimated by the marketing of selected images as art. Such newly reclaimed images include nostalgic sports photojournalism and pictures by renowned Works Progress Administration photographers. The New York Times, for example, proudly advertises that “our historic photographs, with traditional frames, grace the walls of hotels, hospitals, government agencies, law firms, galleries, financial institutions and celebrities’ homes.” Of course, this art-commerce interconnection may be newly lucrative, but it is not entirely new: legendary art/commercial photographer and curator Edward Steichen had wallpaper for his home made from a musical motif supplied by Bettmann. Even Bettmann’s baby picture has come full circle: in the Corbis era, the one transaction on record for this image is for “personal use,” which to a company rep means “to hang on the wall in your house or something.” Thus a personal portrait was put into commercial service, then eventually became domestic art.

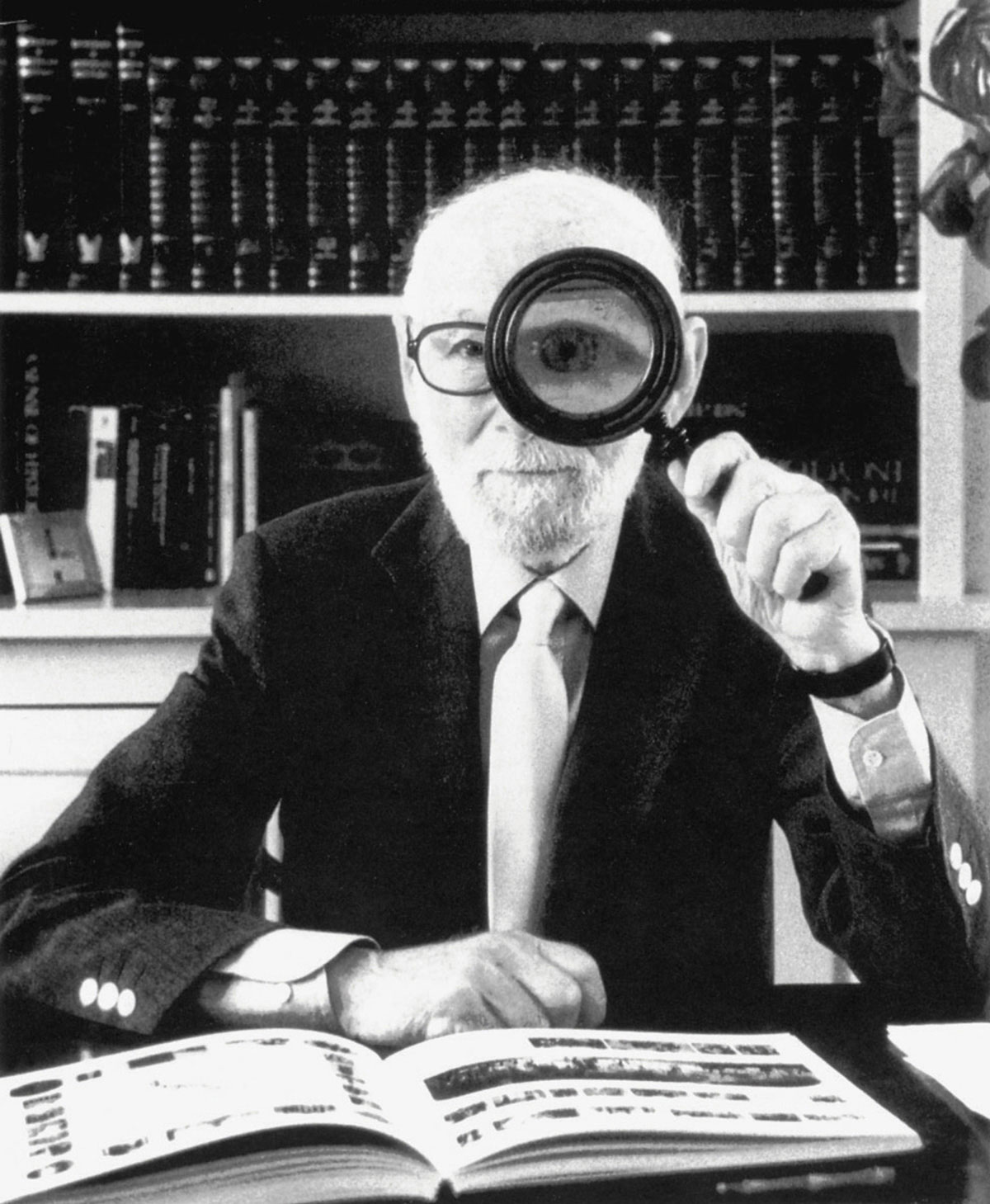

The stock industry thrives on this art-commerce- journalism mix. Heightened contemporary awareness of this interrelationship has, arguably, fostered new interest in works evoking what we like to think of as the pre-critical period, a time of more innocent image consumption. This can be seen in the current popularity of “naive” commercial photography, which takes on a new light in comparison to the critical meta-photography of the Pictures Generation. For example, Portrait of a Man Holding Up Magnifying Glass (undated) is distributed by Retrofile.com, an agency focused precisely on this “retro” market niche. Similar interest now embraces other types of stock media, such as “library music” and “clip art.” In the stock industry, a commonplace is the “twenty-year” rule, the age at which culture attains camp status and therefore becomes re-marketable. As Bettmann himself said, “I hate nostalgia but I’ve made a hell of a living from it.”

And what of the future of this past? When Corbis purchased the Bettmann Archive in 1995, sixty years after its founding and three years before Bettmann’s death, it heralded the incorporation of one of the oldest stock agencies into one of the newest. The most endangered segments of the Archive are now stored at minus four degrees Centigrade, conditions which, in conservation terms, “stop time.” Thus immune to degradation, stock can fast-forward into digital multimedia and a bright future.

Put under a magnifier at the turn of the next century, what will the history of stock photography look like? Practical as well as philosophical, Bettmann conjectured, “Maybe in fifty years no one will be able to read—then the collection will be more valuable than ever.” In a sense, this is already true: images are no longer “read” in the same way they were fifty or a hundred years ago, and this new literacy is arguably the result of re-reading and revaluing the stock photograph.

Jenny Tobias is a librarian at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and a student in the Ph.D. Program in Art History at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.