The Real Thing

The Coke bottle and the third way

Joshua Glenn

It is pathetic, it is very nearly tragic. How much hunger is represented by all these ‘New’ things which give the American public such a quantity of gaseated water to stay their appetites?

—Van Wyck Brooks, America’s Coming-of-Age

In 1915, Van Wyck Brooks published America’s Coming-of-Age. The book-length essay, which established his reputation as one of the era’s leading literary and cultural critics, diagnosed and lamented what Brooks called a debilitating split between two uniquely American attitudes of mind: “Highbrow” and “Lowbrow.”

In 1915, a curvaceous soda-pop bottle was patented in the name of Alex Samuelson, plant superintendent of the Root Glass Company of Terre Haute, Indiana. The bottle had been designed as an entry in a contest sponsored by the nation’s Coca-Cola bottlers, who, like everyone else, had until then used straight-sided bottles.

“Highbrow” and “Lowbrow” are the vernacular short-hand, Brooks noted, for “vaporous idealism,” on the one hand, and “self-interested practicality,” on the other. Though these had formerly been united in the “prevailing American character,” wrote Brooks, in the eighteenth century a rift between the two appeared, as evidenced most strikingly in that century’s greatest American philosophers: Jonathan Edwards and Benjamin Franklin. By “subtracting from his mind every trace of experience,” Edwards invented Highbrow; and in Franklin’s “accommodating wisdom,” Lowbrow first appeared.

During the first half of the 1890s, sales of Coca-Cola syrup shot from 20,000 to 76,000 gallons per year; by the end of 1895, Coca-Cola was sold in every state and territory in the United States. These sales were to upscale soda fountains, where Coca-Cola was decanted into fountain glasses; Asa Candler, founder of the Coca-Cola Company, mistrusted the purity and integrity of bottled soda pop. But in 1899, two Tennessee lawyers—one of whom was named Benjamin Franklin Thomas—proposed to bottle Coca-Cola. Though Candler finally agreed, he insisted that “real Coca-Cola” came in glasses.

Today’s American, wrote Brooks, has been trained—by his teachers and guardians of culture—to feel in himself “the hovering presence of all manner of fine potentialities, remote, vaporous, and evanescent as a rainbow.” But absent Lowbrow’s “humanity, flexibility, tangibility,” he fretted, the Highbrow worldview produces only “a glassy inflexible priggishness ... which paralyzes life.”

The notion of selling Coca-Cola to anyone who walked into a grocery store or saloon clutching a nickel made Candler nervous. From the 1890s through the 1910s, according to Mark Pendergrast’s For God, Country & Coca-Cola, Candler “continued to harbor the Victorian illusion that Coca-Cola must remain a high-class fountain drink, fighting the democratic tide that bottling had unleashed.”

Between official American culture (an “orgy of lofty examples, moralized poems, anthems, and baccalaureate sermons”) and vulgar American humor, Brooks wrote, between the high-minded ethics we’re taught in universities and the nitty-gritty of doing business, between academic pedantry and “slang, journalism, and unmannerly fiction,” there is no connection.

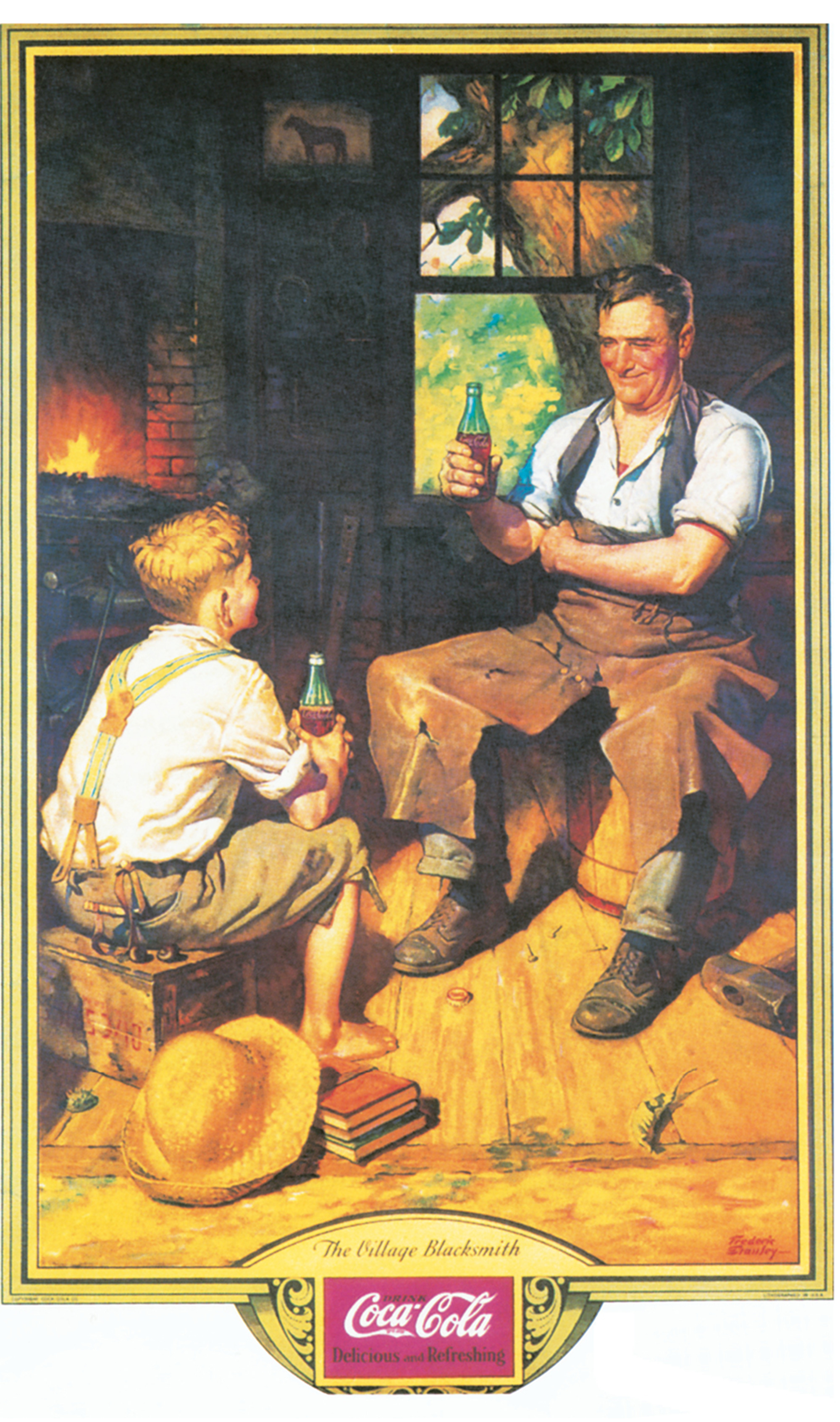

Early Coca-Cola advertisements featured prim and proper women, posed in stiff upright positions, demurely taking a sip. Coca-Cola owed its early popularity, however, to its mixture of small amounts of cocaine and caffeine. Habitual users, known in the 1880s as “Coca-Cola fiends,” couldn’t get enough of it; when calling for Coca-Cola at a soda fountain, they asked for a “dope.”

The purity and integrity of American literature, Brooks wrote, had been preserved only “at the cost of expressing a popular life which bubbles with energy and spreads and grows and slips away ever more and more from the control of tested ideas, a popular life ‘with the lid off.’” Americans were drifting, he insisted, between “desiccated culture” and the effervescent realm of “stark utility.”

By 1905, 119 plants were producing bottled Coca-Cola, and sales kept soaring: by 1909, there were 418 Coca-Cola bottling plants. Concerned fountain operators complained to Candler that bottling diluted the Coca-Cola brand (so to speak), because local distributors sold the drink in a motley assortment of containers. In 1913, Coca-Cola bottlers announced their contest.

Brooks insisted that the supreme goal of life in American society ought to be “self-fulfillment.” The self-fulfilled individual would be one in whom “the hitherto incompatible extremes of the American temperament were fused.” This person would not be a middlebrow; Brooks rejects notions of cultural uplift as analogous to “the frame of mind of business men who retire at sixty and collect pictures.” Instead, he or she would be what we might term a high-lowbrow: an artist and craftsman who would both discover and invent what Brooks called the issues that “make the life of a society.”

According to legend, the 1915 Coca-Cola bottle was both an invention and a discovery. Seeking inspiration for a design that would win the Coca-Cola bottlers’ contest, Alex Samuelson directed a Root Glass Co. accountant to research the beverage’s signature ingredients: the coca plant and the kola nut. The accountant mistakenly produced a drawing of a cocoa bean pod, whose bulbous shape Earl Dean, the Root Glass Co. machinist, then reproduced in bottle form, including the bean’s distinctive ridges. Samuelson’s and Dean’s prototype won the bottlers’ contest hands-down.

“One admits the charms of both extremes,” Brooks wrote, speaking once more of Highbrow and Lowbrow, the academy and Wall Street. “But where is all that is real ... if it is not essentially somewhere, somehow, in some not very vague way, between?”

In the late 1960s, market researchers determined that young Americans despised phonies and valued authenticity. Searching for a slogan that would appeal to young and old, hawk and dove, Coca-Cola’s “Real Thing” campaign debuted in 1969.

What America needed in order to become modern, concluded Brooks, was a “focal centre” in which everything admirably characteristic of Americans—the best of Highbrow and Lowbrow alike—would sum itself up. America needed a totem, he wrote, that would “create everywhere a kind of spiritual team-work.”

According to Mark Pendergrast’s history, bottled Coca-Cola is the world’s most widely distributed product, available in nearly two hundred countries. “Coca-Cola” is the second most universally recognized word on earth (after “OK”), and the curvaceous Coca-Cola bottle has become a symbol of the Western way of life.

Joshua Glenn is a Boston-based writer and editor. He is co-editor of Taking Things Seriously, a collection of photos and essays that will be published by Princeton Architectural Press in the fall of 2007.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.