The Bitter Scribe of Quail Springs

John Samuelson’s Rocks

Sandy Zipp

Each city receives its form from the desert it opposes…

—Italo Calvino

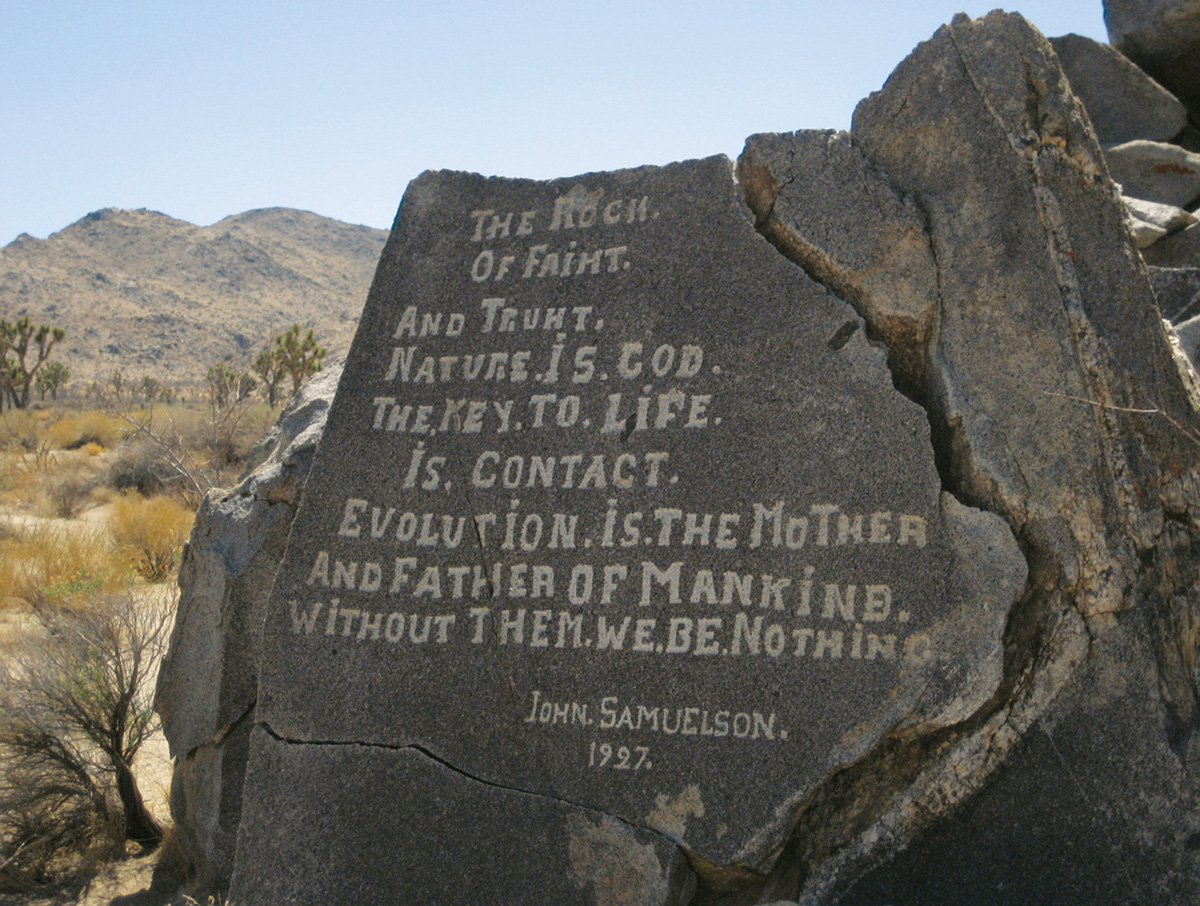

The way out is not far, but long underneath the high midday sun. Sandy and soft underfoot, the track works its way out from the road to an old stream bed and turns away west, skirting to the right of a long granite arm reaching down from the hills ahead. With shifting, unsure footing and hard sun in pinched eyes, we trudge on, pushing through spreading sand and the air, heat-heavy but sharp and still. The desert folds out ahead, its undulations and depths lost to the eye in sheer distance, two miles or more to a ring of hills. They stand against the bleached, searing sky, solid and hazy, shadowless, crumbling rock seeming smooth in the trilling sun. From this far back among the bent, reaching Joshua trees, we can’t see where we’re headed. With time and squint-eyed searching, though, it unmeshes itself from the cliffs behind—a low, dark hill, rocky and tumble-down, unapparent until we draw near how alone it sits, out before the slopes on three sides. We are hurrying now, running and hopping toward the base of this little hill and right up to where an upright rock rests, burnished dark and nearly smooth, facing out to us and the world, crazy and quiet, alone. Words are chipped and gouged out of its face and read:

THE ROCK.

OF FAIHT.

AND TRUHT.

NATURE. IS. GOD.

THE. KEY. TO. LIFE.

IS. CONTACT.

EVOLUTION. IS. THE MOTHER

AND FATHER OF MANKIND.

WITHOUT THEM. WE. BE. NOTHING.

JOHN SAMUELSON.

1927.

This much is clear: sometime in 1926, a Swedish immigrant, the John Samuelson who carved these words, appeared at miner Bill Keys’s ranch east of the Little San Bernardino Mountains in California’s Southern Mojave desert. Keys hired Samuelson to work one of his gold mines, and by 1927 the Swede had set up housekeeping with his wife just north of Quail Springs in the Lost Horse Valley—land that now lies within the bounds of Joshua Tree National Park. His wood and canvas shack sat alone near this small rocky hill; a corral reached out from the hillside into the Joshua trees and creosote. When the pulp writer Erle Stanley Gardner encountered Samuelson at the spring on a cold, blustery day in early 1928, he found an initially silent, lonely man eager to show his visitor the “Rock of Truth,” despite his embarrassment over its grammatical shortcomings.

Gardner said Samuelson needed just a little prodding and a few hot toddies before he could be persuaded to recount the story of his life. Wiping away the sentimental tears of remembrance, Samuelson began to unravel a yarn. Many years before, he said, he had been shanghaied onto a merchant vessel plying the Eastern trade routes. On a long stretch between ports, the weather had turned for the worse. Off the coast of Africa, the storm built into a gale, and the ship foundered. All hands, he assumed, were lost. By some sour stroke of luck, though, he made it over the side and washed ashore, where he was promptly captured by a tribe of natives. They carried him deep into the interior of the “Dark Continent.” After a number of lurid adventures involving man-eating ants, the attentions of a lovely tribal princess, and, of course, a considerable cache of gold, a tribal medicine man forced Samuelson to eat the “Bread of Forgetting.” The bread’s powerful magic knocked him unconscious, and his captors, apparently ready to be rid of this nuisance, delivered him to a colonial outpost. But after waking from his initial slumber, Samuelson found that he was blacking out time and time again for days on end—always just after a rain. What’s more, he couldn’t recall what had happened to him since a terrible storm at sea some months before. He resumed his wanderings at sea, eventually finding his way in his amnesiac state to Boston and the care of a doctor whose specialty was sleeping sickness. Recommending the curative powers of dry air and hot sun, the doctor instructed Samuelson as he might have some Midwestern consumptive: trade tenements and elevated trains for orchards and bungalows. Go West. Slowly, said Samuelson, out in the dry, clear air of the desert, where rain only came once or twice a year, his memory had returned to him in dreams.

Gardner had his doubts about this tall tale. But not one to hesitate when such good material was on offer, the writer paid Samuelson $20 and, later that year, published “Rain Magic”—a eugenics pamphlet in the guise of an adventure story in which Samuelson faces down a “monkey man,” admits to “going native,” and muses about the white man’s “advantages” over the “other races”—in the weekly adventure magazine Argosy. He claims to have visited Samuelson once or twice more in 1928. He found the miner bitter and reserved, but hard at work carving away at the rocks of his little pile, leaving his legacy of dispute with civilization.

WAKE UP YOU TAX

AND BOND SLAVES.

A POLITICIAN IS A BIRD THAT GETS

IN ON THE TAX PAYORS POKET BOOK

FOR A FAT RAKE OF AND HIS FREE KEEP’S.

HE LEAD’S YOU BY THE NOOSE WITH

ONE HAND WITH THE OTHER

HE DIGS IN YOUR POCKET.

A FREIND OF THE BANKER AND BIG

BUSINESS WHY.?.

ARE YOU THE FELLOW

MR. MELLON

THAT GRABED ALL OUR

DOUGH.

AIN’T YOU BETTER UP AND

TELL US.

WHERE IN HELL

DID IT GO.

The desert that Samuelson drifted into was, by the mid-1920s, hardly the barren history-less nowhere the word desert conveys. As lonely as it was and as arduous as the journey to get there must have been, the Mojave was, like Henry David Thoreau’s Walden Pond one hundred years earlier, just about what Gardner called it in the title of his memoirs—a “Neighborhood Frontier” crisscrossed by generations of human interest and speculation. By the time Samuelson reached Quail Springs, he was an early forerunner of a horde of 1930s homesteaders migrating away from Los Angeles’s steady advance into the San Bernardino Valley. Quail Springs is also just over the mountains from Palm Springs—no more than twenty-five miles as the vulture flies from the resort of choice for the stars who were inventing Hollywood’s culture of spectacle and abundance in these years.

Nevertheless, in 1927 Quail Springs felt like a remote place. Far from paved roads, it must have seemed ideal for Samuelson’s life hewed from stone. Belief in the desert’s blankness has led many to erect their dreams and fantasies in its open expanse. From communal Biospheres and massive land art to Borax mines, missile silos, and imagined alien landing zones, those given to making tweaked gestures of wholeness, significance, secrecy, and survival have long found desert soil fruitful. But these rocks—several declarations of skewed transcendentalism, politics, and appraisals of popular figures of the era—seem actually to make something from the desert itself, rather than announce themselves as the something erected in its nothingness. Like tiny desert flowers suckled on a few drops of rain a year, they huddle humbly on their scraggly hill. Resolute and defiant, yes, but they are hardly the ravings of the “rugged individualist” our culture announces for us time and time again. Instead, they’re evidence of how Samuelson came to revive his humanity in the wilderness—in the margin between culture and nature—a borderland that marks the mutual dependence of each state on its supposed opposite. Our Jazz Age Thoreau tells us not that salvation lies in wilderness escape, but that to try to go “out,” back to that wilderness, is only to further explore the confines of “in,” of how we live as a civilization.

GOD

MADE MAN

BUT HENRY FORD

PUT WHEELS UNDER EM

THO. A. MASTER

OF THE GOLD’N RULE

HE. MUST DIE

TO. BE. APRRICIATED.

Why do people come out here—where it seems they shouldn’t be? A good number of paleoanthropologists believe that ages ago protohumans learned to walk erect and hunt food in deserts, not the fertile crescents or river-soaked meadows one might imagine—that it was, in fact, desertification that jump-started this particular phase of human evolution, the very one that led to a highly developed brain, and in turn to language and a plethora of human cultures. Perhaps a residue of this experience lingers somewhere in us. Perhaps humans will “naturally” seek the conditions where they found their distinctly human culture.

If John Samuelson came to revive his humanity here, then did this margin between culture and nature, this borderland like the thrumming inertia between sleep and waking, provide him with the psychic material for a renewed understanding of life? Or is this going out merely the first step? The test for us no longer resides in brute endurance or survival in the face of tooth and claw. Having gone out, one must negotiate the way back in and return to civilization with some vital clue to survival there, in civilization, not in the wilderness.

THE MILK OF

HUMAN KINDNESS

AIN’T GOT THICK

CREAM ON IT FOR

ALL OF US

ASK HOOVER?

The story of Samuelson’s life after Gardner’s last visit to Quail Springs is spotty and unsure. This much seems clear: in 1928, the local branch of the federal land office discovered that he was not a US citizen and voided his title to the land near Quail Springs. He, too, would have to go back in, leaving behind his hill and shack, the wide open air and some strange declarations carved into solid granite. Late that year, he struck camp and headed for Los Angeles.

We know nothing about what the Swede did in the City of Angels, where he lived or if he worked. There’s only one fateful detail. In the official literature available from the Joshua Tree Ranger Station at Twenty Nine Palms, a quote from Samuelson’s wife, Margaret—entirely unmentioned by Gardner—describes him as “a bitter and peculiar person ... the type who would shoot a man for little or no reason.” The same unattributed article also allows as to how there are several known “facts” about the “Bitter Scribe of Quail Springs”: “He was a hard worker, when he worked. He was a hard drinker, when he drank, and he was a hard fighter, when he fought.” And so, true to form, in 1929 Samuelson went to a “dance” in Compton, at that time a township of five thousand souls still ten miles south of Los Angeles proper. Sometime in the course of the evening he got into an argument with two unidentified men. There are few details to be had, but by all accounts Samuelson shot and killed both men. He was apprehended on the spot. Here, however, the record is of two minds. One account has him immediately convicted of murder. The other story, told by Gardner, is that he was declared insane and excused from a criminal trial. Either way he was sent north to Mendocino County to the California State Hospital in 1930; it seems he was condemned to live out his days hundreds of miles from the dry, curative desert amongst the wet northern pines.

JUDGE BEN LINDSEY

A. MAN THAT

UNDERSTANDS HUMANETY

AND BIG ANOUGH

TO. LIVE. IT.

STUDY NATURE OBEY THE LAWS

OF IT YOU CAN’T GO WRONG

IT PAYES COMPUND ENTEREST

FOR LIFE AND NOT ONE PENNY

ENVESTED?

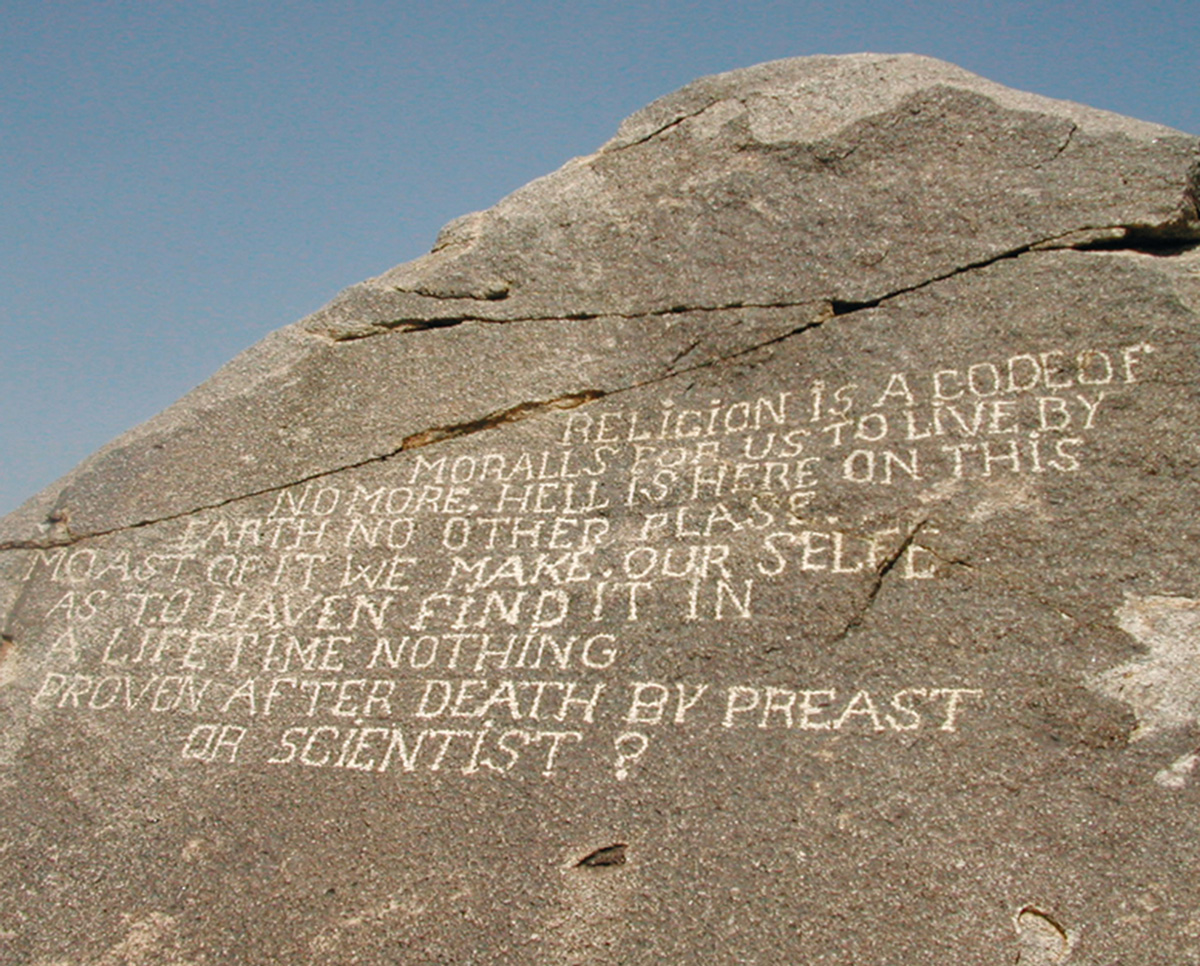

Clearly the narrative lenses we’ve been given to view John Samuelson are many, and none of them too reliable. Samuelson may be a fantastic liar or Gardner an even more outlandish storyteller. Any truth is lost to time. Opting out of this bind makes for a more intriguing legacy for the “Bitter Scribe of Quail Springs.” There are, as it turns out, seven rocks lurking around Samuelson’s hill, and two stones have two declarations on their faces, making for nine statements all told. Sitting two to three miles from the nearest road, in open desert, they are rarely seen and have been left virtually untouched. These are clearly not the hazy mutterings of an amnesiac just arrived on American shores. They improvise on odd details of life in 1920s America. Recalling a brand of settler populism that the speculative, boom-time Twenties did much to destroy, they also offer oblique and bitter meditations on time, religion, nature, and destiny.

Commerce Secretary when Samuelson lived at Quail Springs, Herbert Hoover was then seen as a leading Progressive technocrat, a lonely voice warning Calvin Coolidge that the bull market was getting out of hand. He had led successful efforts to regulate radio, the industry at the leading edge of the 1920s stock bubble. He had been known as a great humanitarian for his leadership in preventing mass starvation in Belgium and Russia after World War I. Directing engineering and relief efforts during the 1927 flood, he had saved many thousands of lives in the Mississippi Delta. Was Hoover a lonely dispenser of “the milk of human kindness,” the only politician with the gumption to stand up to “the banker and big business?” Or had this Swedish drifter soured on Hoover long before Bonus Marchers, shantytowns, and bank failures left most of the nation convinced that the reserved Iowan individualist was a do-nothing bumbler in the face of spreading international tragedy in the early years of the Depression? It’s hard to say, just as it’s difficult to tell whether Samuelson admired Henry Ford’s perfection of the assembly line, strict workplace rules, anti-Semitism, and moral rigidity, or expressed his “aprriciation” for Ford’s achievements with fond hopes for the carmaker’s early expiration. The $5-day that Ford instituted at his Highland Park plant in 1914 was big money. After that, Ford workers could buy Ford cars, but only by chaining themselves to the ever-moving assembly line. Maybe that didn’t sit well with Samuelson’s irascible populist temper, or maybe Samuelson the drifter gave Ford credit for enabling America’s God-given democracy of movement, the right to up and split.

It’s not surprising that financier and Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon—early architect of a tax-cuts-for-the-rich, trickle-down economics—earns only Samuelson’s scorn. Or that he admired Judge Ben Lindsey. Lindsey was a nationally famous Progressive-era judge from Colorado, forgotten now, who spoke out for economic justice, women’s suffrage, and fairness in sentencing for juvenile offenders. (He saw them as misguided, as “delinquents” rather than as criminals, and the separate juvenile courts he established in Colorado were copied around the country.) But if Lindsey is ever remembered any longer it is for his campaign to legalize “companionate marriage” and his role as what his biographer calls “the chief spokesman in America of the sexual revolution of the 1920s.” Lindsey was less than concerned about the loosening of morals that so troubled the remnants of America’s Victorian establishment in the 1920s. In The Revolt of Modern Youth from 1925 and The Companionate Marriage of 1927, Lindsey defended fallen women and open marriage and divorce. He recommended birth control—calling for decriminalizing contraception—as a way to keep marriages child-centered, liberate women, and reduce reckless abortion. Railing against dour, hectoring clergymen and a society that tried to keep kids in line through fear, he celebrated young sexual experimenters whose attempts to adapt to a new world were only made tragic by economic injustice and the “social ills” of “broken homes, desertions, sorrow” that stigmatized young women without means. In The Companionate Marriage, Lindsey barnstormed for modernism in nuptial practices—calling for open, contractual marriages based on human partnerships (and the right to divorce by mutual consent) rather than marriage ordained and constricted by the “natural” bonds of God and church. Eventually his “humanety” got him drummed out of Colorado, and, like Samuelson, he headed for Los Angeles.

Samuelson’s sheer cussedness, his ambiguous ponderings on politics, and his righteous blasphemy give the impression of a small-time Mencken. You get the idea he would have been the scourge of the local newspaper’s letters page. But most of these rocks are meditations on nature. And for Samuelson nature gains its power under the close and intimate influence of human action. Maybe it was the fact of making them, the long hours under the sun with hammer, chisel, or pick that pressed home the rough embrace of human artifice and nature. “Study nature” and “obey the laws of it,” he wrote; it will be an investment that “payes compound enterest.” But it is not money, but some other currency, some other energy of human commerce, that will be our ultimate payoff—is it not clear that this energy is the exchange made between culture and nature itself, the spiritual politics of “contact?” Put all these carvings together and they say it themselves—there’s a haphazard logic of connection between all these awkward, stone assertions. They make it seem entirely sensible, natural even, that they’ve been waiting here out away from everything to give us a chance to put the world together in new ways. Like sparks struck with flint off their rough faces, they make contact, speaking out across time to us in a language that seems unhinged, but comes together the more you look around.

MOTHER TIME.

NEITHER WEALTH LAW’S NOR ARMY’S CAN STOP THE

HUMAN MIND FROM CREATING NEW OR EMPROVE UP ON

THE PRESENT DAY RELIGION AND GOVERNMENT.

WATER IS SAFT ONLEY HARD IN THE CHEMICALL’S

BUT WITH TIME THE OCEAN CAN GRIEND THE

HARDEST GRANIT INTO A POWDERED SAND.

SO WITH TIME WILL THE HUMAN RACE GRIEND

OUT ITS OWN DESTINY’S REGARDLESS OF THE

OPPOSITION OR PARTY IN POWER.

More than sixty-five years have passed since John Samuelson left these parts, but, like Samuelson, the land here continues to be ill at ease with the world looming just beyond the near horizon of hills. Maybe it’s the wide, clear skies. The bright, open air. Too much light in my eyes. But the desert brings on strange affiliations, unexpected links, the strange vertigo of digression, a desert madness of connective possibility where un-looked-for combinations suddenly seem only natural. John Samuelson’s ruins start to appear more than lost and nothing less than prophetic. How else to arrive here but by the bent paths of off-kilter association? Samuelson may have put his words in stone, but he’s still caught in the web of fantasy and prophecy that he and Erle Stanley Gardner have spun around him. It actually seems fitting that John Samuelson’s alleged story was told in the pulp fiction of the day, because his life and work seem to predict the modern tales of true-crime that still haunt these parts.

Sandwiched between a Marine base to the North and a National Park to the South, the towns along nearby Route 62 seem mired in violence. Over the past decade or so they have endured moral panics over gang activity, a grisly rape and murder of two local girls by a Marine, and constant low-level petty crime and domestic violence—all of it turned up a notch by the so-called methamphetamine “epidemic” plaguing the Southwest. Self-described upstanding citizens of these towns—kin, perhaps, to those who ran Ben Lindsey out of Colorado—may dispute the desert madness, preferring to lay the blame for the area’s half-cocked dissolution at the feet of the town’s undesirable elements, but there’s no mistaking that this is a place that has floated free, that has lost all organic “contact” with its environment. Everywhere there is a silent, unnerving despair slipping up from the cracks in the baking asphalt and from behind the boosterish Chamber of Commerce slogans. Mistaking the desert’s openness for emptiness, this once and former retreat from the world is stifling itself, “grinding out” the frightful human “destiny” John Samuelson spoke of in solid, enduring granite not far away, but in another time and place altogether. Long and far indeed, but fitting for this place where one man learned to speak in the landscape, carving out a series of warnings to a human civilization sprung from the desert that is maiming itself and the land as it returns there.

RELIGION IS A CODE OF

MORALLS FOR US TO LIVE BY

NO MORE. HELL IS HERE ON THIS

EARTH NO OTHER PLASE.

MOST OF IT WE MAKE. OUR SELFE.

AS TO HAVEN FIND IT IN

A LIFETIME NOTHING

PROVEN AFTER DEATH BY PREAST

OR SCIENTIST?

John Samuelson never returned to the Mojave. As far as I can tell the story ends something like this: sometime in 1930, he managed to escape from his keepers in Mendocino. Eluding pursuers, he made his way northward through Oregon and into Washington. Apparently, he finally landed at a logging camp somewhere in Washington, from where he wrote a series of letters to Bill Keys, his old employer at Quail Springs. The first of these was sent in 1940 and the last in 1954. In his letters, which apparently have not survived, Samuelson said he dreamed of returning to the desert but feared he would be caught by the law. He knew he’d never see the desert again. The last letters Keys got from Washington, a short time after Samuelson’s final missive in 1954, came from the camp’s officials. They contained the news that Keys had no doubt long expected. The first revealed that his old employee had been hurt in a logging accident. Then, not long after, came the final note. After lingering near death for some time, Samuelson succumbed to his injuries and died.

Sandy Zipp lives in Long Beach, CA. He has written for the Baffler, Metropolis, In These Times, and the New York Times and is now at work on Manhattan Projects: The Rise and Fall of Cold War Urban Renewal in New York City (forthcoming, Oxford University Press). He has a Ph.D. in American Studies from Yale and will begin teaching urban and cultural history at Brown University this fall.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.