Tatlin, or, Ruinophilia

The avant-garde and the off-modern

Svetlana Boym

The early twenty-first century exhibits a strange ruinophilia, a fascination with ruins that goes beyond postmodern quotation marks. In our increasingly digital age, ruins appear as an endangered species, as physical embodiments of modern paradoxes reminding us of the blunders of modern teleologies and technologies alike, and of the riddles of human freedom.[1]

Ruin literally means “collapse” but actually, ruins are more about remainders and reminders. A tour of ruins leads you into a labyrinth of ambivalent prepositions—“no longer” and “not yet,” “nevertheless” and “albeit”—that play tricks with causality. Ruins make us think of the past that could have been and the future that never took place, tantalizing us with utopian dreams of escaping the irreversibility of time. Walter Benjamin saw in ruins “allegories of thinking itself,” a meditation on ambivalence.[2] At the same time, the fascination with ruins is not merely intellectual but also sensual. Ruins give us a shock of vanishing materiality. Suddenly our critical lens changes and instead of marveling at grand projects and utopian designs we begin to notice weeds and dandelions in the crevices of the stones, cracks on modern transparencies, and rust on the discarded Blackberries in our ever more crowded closets.

While half-destroyed buildings and architectural fragments might have existed since the beginning of human culture, ruinophilia did not. There is a historic distinctiveness to the “ruin gaze” that can be understood as the particular optics that frames our relationship to ruins. The ruin gaze is colored by nostalgia, but nostalgia, too, is not what it used to be. Its object is forever elusive, and our way of making sense of this longing for home is also in constant flux.

In my understanding, nostalgia is not merely anti-modern, but coeval with the modern project itself.[3] Like modernity, nostalgia has a utopian element, but it is no longer directed toward the future. Sometimes it is not directed toward the past either, but rather sideways. The nostalgic feels stifled within the conventional confines of time and space. The ruins of twentieth-century modernity, as seen through the contemporary prism, both undercut and stimulate the utopian imagination, constantly shifting and deterritorializing our dreamscape.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Georg Simmel formulated a theory of ruins that resonates with contemporary preoccupations. According to Simmel, ruins are the opposite of the perfect moment pregnant with potentialities; they reveal in “retrospect” what this epiphanic moment had in “prospect.”[4] Yet they do not merely signal decay but also a certain imaginative perspectivism in its hopeful and tragic dimension. Simmel saw in the fascination with ruins a peculiar form of “collaboration” between human and natural creation. The contemporary ruin-gaze is the gaze reconciled to perspectivism, to conjectural history and spatial discontinuity. The contemporary ruin-gaze requires an acceptance of disharmony and of the contrapuntal relationship of human, historical, and natural temporality. Rather than postmodern, we can call it “off-modern”: it involves exploration of the side-alleys of twentieth- century history at the “margins of error” of major theoretical and historical narrative, tracing alternative genealogies of modernity from Viktor Shklovksy’s diagonal “knight’s move” to Tatlin’s spirals.

Looking back at the ruins of the twentieth century, we see more paradoxical mergers: between suprahuman state models and human practices, between individual aspirations and collective pressure, between ascending dreams and down-to-earth everyday survivals. The ruin-gaze challenges the notion of the “originality of the avant-garde” (Rosalind Krauss) and of the continuity of the utopian vision between the artistic avant-garde and the socialist state (Boris Groys).[5] Instead, it reveals the internal diversity of the avant-garde, its singularities and eccentricities that proved to be as historically relevant and persistent as its visionary elements and collective utopianism.

In fact, the tower embodied many explicit and implicit meanings of the word revolution. The word came from scientific discourse and originally meant repetition and rotation. Only in the seventeenth century did it begin to signify its opposite: a breakthrough, an unrepeatable event. The history of the tower reflects upon the ambivalent relationship between art and science, revolution and repetition. Shaped as a spiral, a favorite Marxist-Hegelian form, the tower culminated in a radical opening on top, suggesting unfinalizability, not synthesis. In fact, the tower commemorated the short-lived utopia of the permanent artistic revolution, of which Tatlin was one of the leaders. He declared that the revolution did not begin in 1917 but in 1914 with an artistic transformation; political revolutions followed in the steps of the artistic one, mostly unfaithfully.

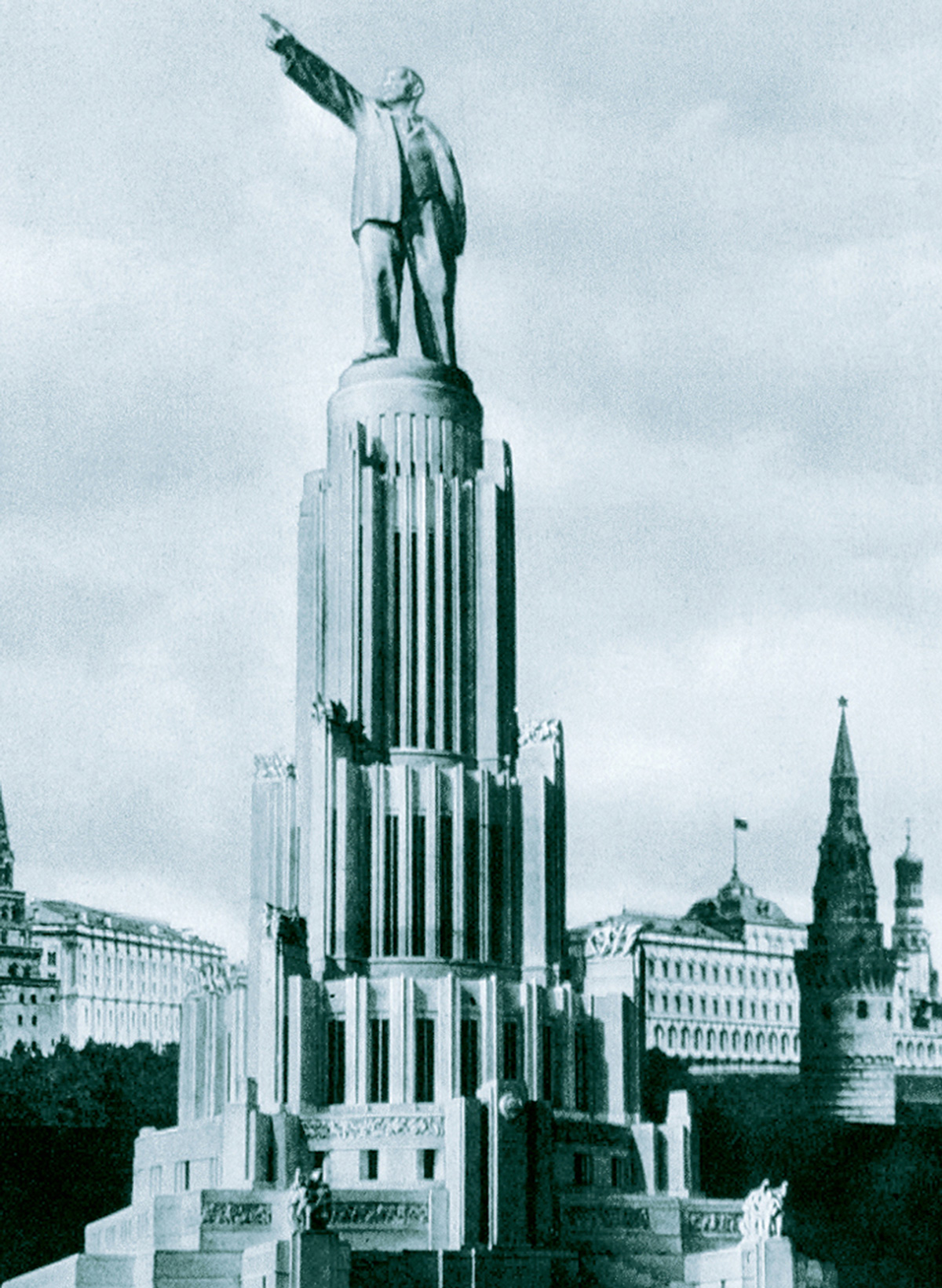

The art historian Nikolai Punin described the monument as the anti-ruin par excellence. In his view, Tatlin’s revolutionary architecture reduced to ashes the Classical and Renaissance tradition, and the “charred ruins of Europe are now being cleared.”[6] The writer Ilya Ehrenburg believed that the tower was an answer to all those figurative official monuments that he called “plaster idiots,” including Marx’s “which as a tribute to contemporary thought has been trimmed by an Assyrian barber.”[7] Tatlin’s tower sabotaged the perfect verticality of the Eiffel Tower by choosing the form of a spiral and leaning to one side.

Yet uncannily, Tatlin’s monument was not free from the “ruin’s charm” despised by revolutionary thinkers and artists from Malevich to Guy Debord. Lissitsky praised Tatlin’s tower for its synthesis of technical and artistic knowledge, old and new forms: ”Here the Sargon Pyramid at Khorsabad was actually recreated in a new material with a new content.”[8] The edifice in Khorsabad was actually a ziggurat, a pyramidal structure with a flat top that most likely corresponded to the mythical shape of the Tower of Babel, which in turn resembled the ziggurat at Babylon called Etemenenanki.[9] So in its attempt to be the anti-Eiffel Tower, Tatlin’s tower started to resemble the Tower of Babel, which was in itself an unfinished utopian monument turned mythical ruin. Moreover, in the case of the Tower of Babel, the tale of architectural utopia and its ruination is mirrored by the parable about language. The Tower of Babel, we recall, was built to ensure perfect communication with God. Its failure ensured the survival of art. Since then, every builder of a tower has dreamed of touching the sky, though, of course, the gesture remained forever asymptotic.

Every “functional” modern tower evokes this mythic malfunctioning of the original communication. Roland Barthes’s poetic commemoration of the uselessness of the Eiffel Tower could easily apply to its Soviet rival as well. Barthes wrote that while Eiffel himself saw his tower “in the form of a serious object, rational, useful, men return it to him in the form of a great baroque dream which quite naturally touches on the borders of the irrational.”[10] Much of visionary architecture, in Barthes’s view, embodies a profound double movement; it is always “a dream and a function, an expression of a utopia and instrument of a convenience.” Barthes’s Eiffel Tower was an “empty” memorial that contained nothing, but from the top of it you could see the world. It became an optical device for a vision of modernity. Tatlin’s tower played a similar role as an observatory for the palimpsest of revolutionary panoramas that included ruins and construction sites alike.

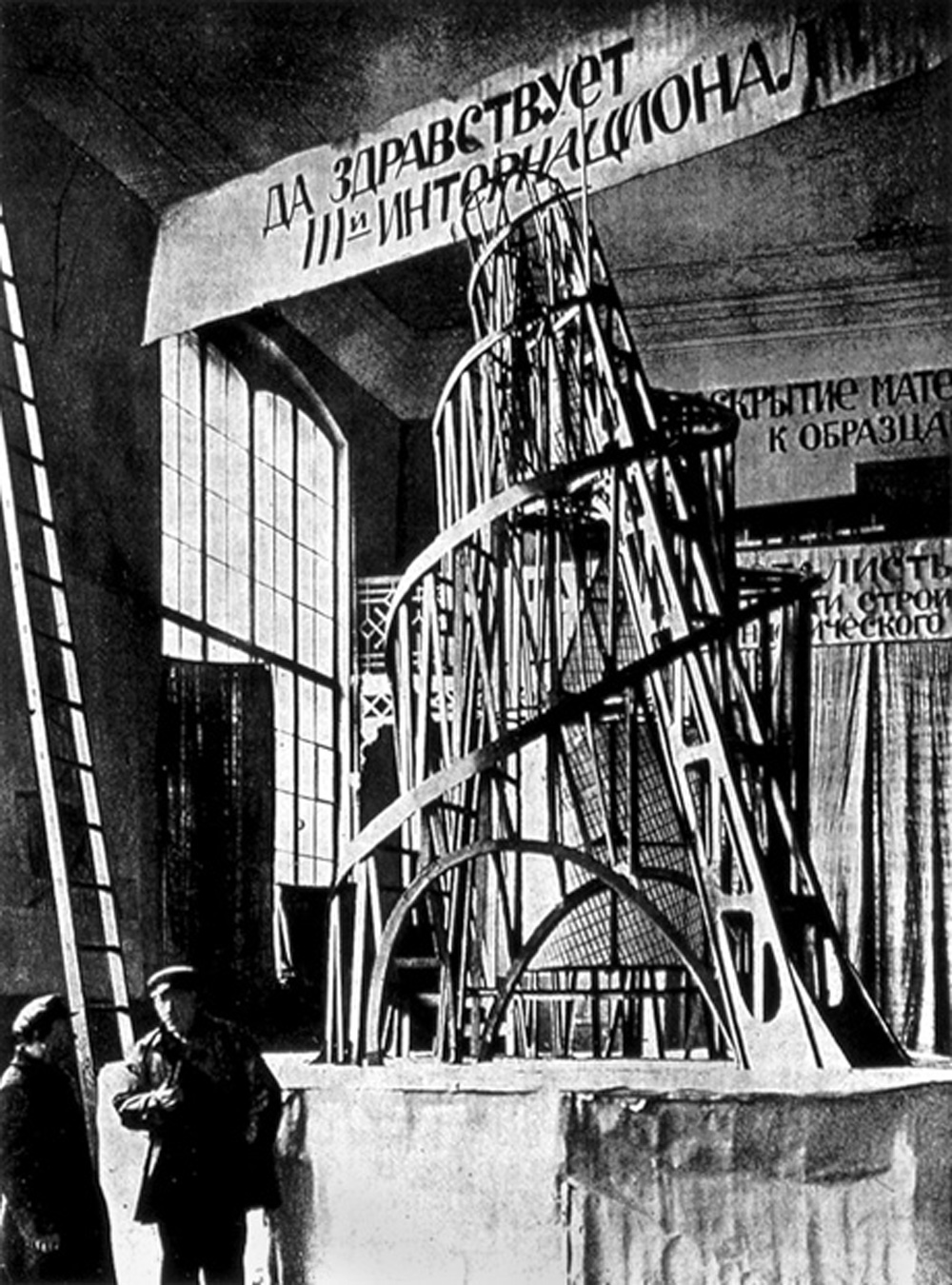

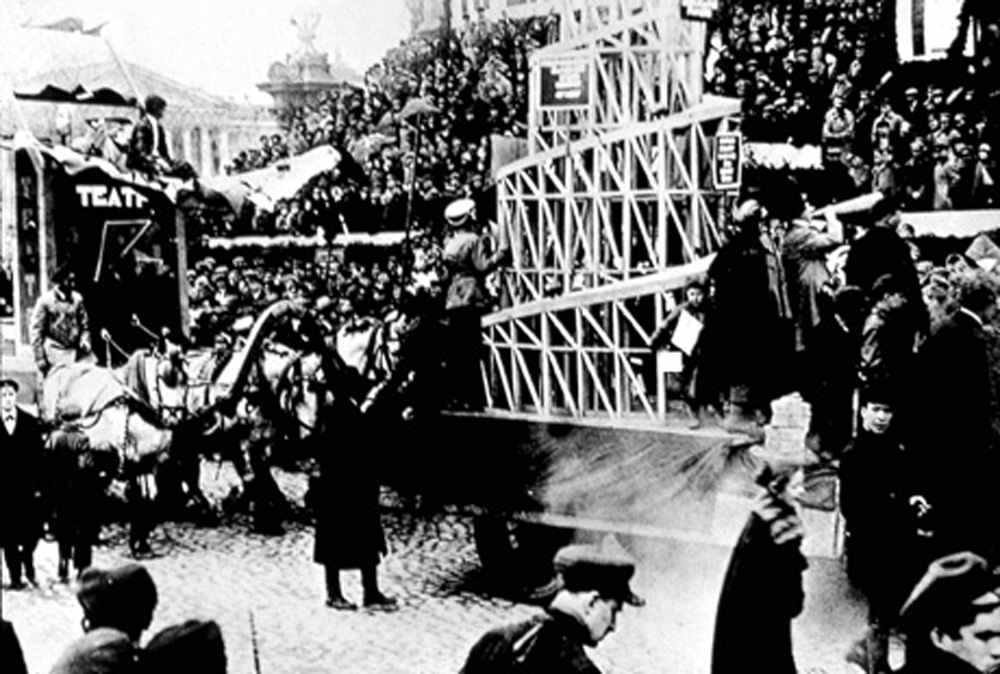

Unlike the Eiffel Tower, Tatlin’s was never built. The failure of its realization is not due merely to engineering problems and concerns about feasibility. The tower was both behind and ahead of its time, clashing with the architectural trends of the Soviet regime. It appeared as an incomplete theatrical set, not gigantic but human-scale, a testimony to revolutionary transience. Leon Trotsky wrote that Tatlin’s project gave “an impression of scaffolding which someone has forgotten to take away.”[11] In fact, it remained “a scaffolding” for future architecture. Tatlin, faithful to avant-garde “technique,” left no professional architectural drawings of the tower, offering space for unpredictability and imagination. Even the original model of the tower has not been preserved. Most of the few remaining photographs are from November 1920 and May 1925 when the model of the tower was paraded during Soviet demonstrations.[12] In 1920, articles about the tower appeared in the Munich art magazine Der Ararat and caught the attention of the emerging Dadaists. “Art is dead,” declared the Dadaists. “Long live the Machine Art of Tatlin!”[13] Yet to some extent, the Dadaists’ celebration of the death of art via Tatlin’s spiral guillotine was an act of cultural mistranslation and a common Western misconception about the Russian avant-garde. By no means was Tatlin a proponent of machine-assisted artistic suicide, especially not at the time of the revolution when “the death of art” was more than a metaphor. Instead, Tatlin argued against the “tyranny of forms born by technology without the participation of artists.” His own slogans, “Art into Life” and “Art into Technology!”, do not merely suggest putting art in the service of life or technology, or putting life in the service of political or social revolution.[14] Rather, they propose to revolutionize technology and society by opening horizons of imagination and moving beyond mechanistic clichés and what Tatlin dubbed “constructivism in quotation marks.”[15]

From the very beginning, the Tatlin tower engendered its double—a discursive monument almost as prominent as its architectural original. The writer and literary theorist Victor Shklovsky was one of the few contemporaries who appreciated the unconventional architecture of the tower. For him, this was an architecture of estrangement: its temporal vectors pointed toward the past and the future, toward “the iron age of Ovid” and the “age of construction cranes, beautiful like wise Martians.”[16] To cite Walter Benjamin, in this case “modernity quotes prehistory.” The air of the revolution functions as the project’s immaterial glue. Thus, at the origins of modern functionalism in architecture is the poetic function as well as engineering inventions. Describing the “semantics” of the tower, Shklovsky speaks of poetry: “The word in poetry is not merely a word, it drags with it dozens of associations. This work is filled with them like the Petersburg air in the winter whirlwind.”[17] Tatlin’s tower appears as a monument to the poetic function itself. In its foundation, the two meanings of the word techne—that of art and of technical craft—continuously duel with one another.

Hence the tower is not merely an engineering failure but an exemplary case study of constructivist architecture. Architecture was imagined as archi-art, as a framework for a worldview and a carcass for futurist dreams. This made it both more and less than architecture in the sense of a built environment. Revolutionary architecture offered a scenography for future experimentation and embodied allegories of the revolution. The most interesting examples of this “archi-architecture” were not built monuments but rather dreamed environments, models, or unintentional memorials. Shklovsky describes his own ludic ruin/construction site that lays a foundation for the subversive practice of estrangement.

It is little known that Shklovsky was the first to describe the Soviet Statue of Liberty in the same collection of essays in which he reviews the Tatlin tower. In The Knight’s Move (1919–21) written in Petrograd, Moscow, and Berlin, Shklovsky offers us a parable about the metamorphoses of historical monuments that functions as a strange alibi for not telling “the whole truth” or even “a quarter of the truth” about the situation in post-revolutionary Russia. In 1918 in Petrograd, a monument to Tsar Alexander III was covered up with a cardboard stall on which were written all kinds of slogans celebrating liberty, art, and revolution.[18] The “Monument to Liberty” was one of those transient, non-objective monuments that exemplified early post-revolutionary “visual propaganda” before the granite megalomania of the Stalinist period:

There is a tombstone by the Nicholas Station. A clay horse stands with its feet planted apart, supporting the clay backside of a clay boss ... They are covered by the wooden stall of the “Monument to Liberty” with four tall masts jutting from the corners. Street kids peddle cigarettes, and when militia men with guns come to catch them and take them away to the juvenile detention home, where their souls can be saved, the boys shout “scram!” and whistle professionally, scatter, run toward the “Monument to Liberty.” Then they take shelter and wait in that strange place—in the emptiness beneath the boards between the tsar and the revolution.[19]

In Shklovsky’s description, the monument to the tsar is not yet destroyed and the monument to liberty is not entirely completed. A dual political symbol turns into a lively and ambivalent urban site inhabited by insubordinate Petrograd street kids in an unpredictable manner. In this description, the monument acquires an interior; a public site becomes a hiding place. Identifying his viewpoint with the dangerous game of the street kids hiding “between the tsar and the revolution,” Shklovsky is looking for the third way—the transitory and playful architecture of freedom. He performs a double estrangement, defamiliarizing both the authority of the tsar and the liberation theology of the revolution. The “third way” here suggests a spatial and a temporal paradox. The monument caught in the moment of historical transformation embodies what Walter Benjamin called the “dialectic at a standstill.” The first Soviet statue of liberty is at once a ruin and a construction site; it occupies the gap between the past and the future in which various versions of Russian history coexist and clash.

In Shklovsky’s view, Tatlin’s tower and other transitional monuments to liberty become monuments to estrangement, not to utopia. Estrangement is an exercise of wonder, of thinking of the world as a question, not as a staging of a grand answer. Thus, estrangement lays bare the boundaries between art and life but never pretends to abolish or blur them. It does not allow for a seamless translation of life into art, nor for the wholesale aestheticization of politics. Art is only meaningful when it is not entirely in the service of real life or realpolitik, and when its strangeness and distinctiveness are preserved. So the device of estrangement can both define and defy the autonomy of art.

Hence, such an understanding of estrangement is different from both Hegelian and Marxist notions of alienation. Artistic estrangement is not to be cured by incorporation, synthesis, or belonging. In contrast to the Marxist notion of freedom that consists in overcoming alienation, Shklovskian estrangement is in itself a form of limited freedom endangered by all kinds of modern teleologies.

By the mid-1920s, the artistic climate in Soviet Russia had changed significantly. In her diary of 1927, Lidiia Ginzburg, the literary critic and younger disciple of Tynianov and Shklovsky, observed: “The merry times of laying bare the device have passed (leaving us a real writer—Shklovsky). Now is the time when one has to hide the device as far as one can.”[20] The practice of aesthetic estrangement had become politically suspect already by the late 1920s; by 1930, it had turned into an intellectual crime. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Tatlin worked on another monument of avant-garde technology, the artist’s namesake—Letatlin (a neologism that combines the Russian verb “to fly”—letat’—and the name of the author). If the tower represented a dream of the perfect collective, the new agora for the Third International, Letatlin was an individual flying vehicle. A biomorphic structure, somewhere between a costume and a vehicle, it resembled the firebird from Russian fairy tales stripped to its bare bones. Today, it looks like a vestige of a modern Icarus, a tribute to the dream birds and nonfunctional machines imagined by artists since the Renaissance. Since Tatlin hoped to have his projects sponsored by the aviation industry, his essay on art and technology was introduced by an epigraph quoting Stalin: “Technology decides everything.” Only in Tatlin’s case, technology did not function according to the program. Neither a celebration of Soviet engineering nor a solemn statement of Russian cosmism, Letatlin was an intimate artistic vehicle, a graceful monument to a dream, not a journey into another world. There was nothing otherworldly or technological about Letatlin. Most likely it could not fly. Not in a literal sense, at least.

Letatlin and the tower belong to a very different history of technology, an enchanted technology founded on charisma as much as calculus, linked to premodern myths as well as to modern science. What remains of Letatlin are the vertebrae of the wings, the drawings that resemble those of Leonardo da Vinci. What remains of the Monument to the Third International is an architectural skeleton in an old photograph. Both unrealized monuments appear in retrospect poignantly anthropomorphic and interconnected. The tower resembles the ruin of a mythical space station from which Letatlins could soar into the sky.

Tatlin’s artistic life from mid-1920s to the mid-1930s is rich in contradictions refracting its time. He designed the coffin of Russia’s revolutionary poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, who committed suicide in 1930. In 1931, Tatlin received the honor of “distinguished artistic worker” and in 1932 opened a solo exhibition, the only one in his lifetime, where the critics observed—erroneously, it seems—that Tatlin had moved from “art to technology.” In 1934, the OGPU invited him together with other artists to observe the construction of the White Sea Canal, one of the early sites of Stalin’s slave labor. After a few other failed attempts at designing public architecture, Tatlin gradually retreated from the artistic public sphere; he did illustrations for Kharms and other children’s writers (before some of them disappeared during the purges) and worked on theater design. At the official “Artists of Russia” exhibit (1933), Tatlin’s works were shown in a small hall dedicated to “formalist excesses” (a successful predecessor of the “Degenerate Art” exhibition in Germany). Soviet critics proclaimed that Tatlin’s works demonstrated “the natural death of formal experiments in art” and declared Tatlin to be “no artist whatsoever.”

What do artists do when they outlive their cultural relevance? In the Soviet case, we know very little about the last fifteen years of work of the founders of the visual avant-garde, including Vertov and Tatlin who died in 1954 and 1953, respectively. What can an avant-garde artist make after his officially declared death?

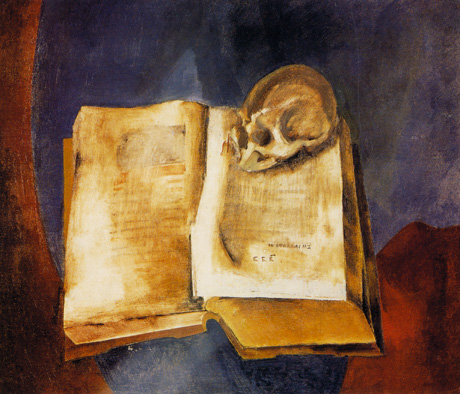

Tatlin’s “postmortem” work consists—literally—of nature mortes, in a brown and gray palette painted on the thinly concealed surfaces of the old canvas or icons and of desolate rural landscapes on the backdrops of Socialist Realist theater productions. At first glance, these works seem untimely and in their technique resemble some of Tatlin’s earliest experiments with figurative painting before 1914. In my view, the belated untimeliness of Tatlin’s still lives and landscapes speaks obliquely of their time—the time of purges and war. Still lives are reminders of the other, non-revolutionary rhythms of everyday life. They preserve the dream of home, of domesticated nature, and of a long-standing artistic tradition. Tatlin’s still lives are devoid of visual sensuality; they represent endless variations on the same themes: wild onions and radishes, nondescript garden flowers, knives stuck into the browning flesh of not-so-fresh meat, a skull with an open book. These look like memento mori, foregrounding the fragility of even the most frugal domesticity.[21] There is a subtle tension between the ahistorical still lives and the dates on the minimal caption: 1937, 1944, etc. Still life was not politically suspect and was one of the few remaining genres on the margins of Socialist Realism that survived extreme censorship. Strangely, this was one of the favorite genres of prison art promising a temporary escape into a quieter plane of human existence. The maker of still lives excels in the art of minor variations, performing a manual labor of cultural memory.

Moreover, the closer we look at Tatlin’s still lives, the more they appear to be exercises in double vision, but not in a conventional sense of political double-speak. Rather, there is a tension between the figurative flowers and the abstract background. In the foreground are the sparse still lives, and in the background the thickly painted planes from which the counter-reliefs once sprung. These unspectacular and belated stage sets were abandoned by the biomorphic revolutionary Icaruses. No Letatlin would land here anymore; no foundation of a revolutionary tower can be laid on this swampy soil of fear. Tatlin’s late works resemble a desolate “natural setting” in which the projects of the avant-garde have turned into the ruins of the revolution.

• • •

And yet, nevertheless, still … artistic works have their own paradoxical lives.[22] The tower remained a phantom limb of the nonconformist tradition of twentieth-century art, in paper architecture, conceptual installations, and new design, opening up another conjectural off-modern history. Talin’s tower was not destined to exist in the open space of the city. Instead, it acquired a second life in many models built around the world since the 1960s. One could distinguish between faithful reconstructions and reflective appropriations. One of the most faithful replicas was reconstructed on the floor of the mosaic factory where Tatlin worked in the last years of his life. And the most recent Russian reconstruction of the tower took place between 1986 and 1991 by a group of young architects and designers who performed a meticulous analysis of Tatlin’s sketches and few photographs.[23] Never realized as a radical revolutionary monument, the tower came into material existence as “artistic heritage.” In the post-Soviet remake of the tower, reconstruction and ruination of the revolutionary ideals coincided.

On the other hand, creative if unfaithful appropriations of Tatlin’s project lead to a fascinating intersection between architecture and installation. Ilya Kabakov used the spiral shape of the tower for his House of Projects, returning utopia back to its origins—not in life but in art. Jane and Louise Wilson’s Free and Anonymous Monument, a project based on decaying post-war modern architecture, produces flickering shapes of Tatlin’s tower through a cinematic perspective. Similarly, in some of Gordon Matta-Clark’s “cuts” through buildings slated for demolition, Tatlin’s tower, the model of future architecture, appears via negativa—in the shapes of the cut itself, which echoes the tower’s Babelian spiral. It continues to haunt contemporary art like a specter of lost opportunities.

In these architectural and artistic projects, the off-modern reveals itself in a form of a paradoxical ruinophilia, and in the recycling of industrial forms and materials. New buildings or installations neither destroy the past nor rebuild it; rather, the architect or the artist co-creates with the remainders of history and collaborates with modern ruins, redefining their functions—both utilitarian and poetic. The resulting eclectic, transitional architecture reveals a spatial and temporal extension into the past and the future, into different “existential topographies” of cultural forms. The off-modern gaze acknowledges the disharmony and the contrapuntal relationship between human, historical, and natural temporalities. It is reconciled to perspectivism and conjectural history. Thus, the off-modern perspective allows us to frame utopian projects as dialectical ruins—not to discard or demolish them, but rather to confront them and to incorporate them into our own fleeing present.

The portions of this text on Tatlin’s tower are a revised excerpt from Svetlana Boym’s forthcoming book Architecture of the Off-Modern, a FORuM Project Publication of the Temple Hoyne Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture at Columbia University.

- For more on the theory of ruinophilia, see my forthcoming article “The Ruins of the Avant-Garde” in Andreas Schonle and Julia Hell, eds., The Ruins of Modernity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008).

- Walter Benjamin, The Origin of German Tragic Drama (London: NLB, 1977), pp. 177–178.

- See Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia (New York: Basic Books, 2001).

- Georg Simmel, “The Ruin,” in Kurt H. Wolff, ed., Essays on Sociology, Philosophy and Aesthetics (NY: Harper and Row, 1965), 262. “This is as it were a counterpart of that fruitful moment for which those riches which the ruin has in retrospect are still in prospect.”

- I refer here to Rosalind Krauss, The Originality of the Avant Garde and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1985) and to Boris Groys, The Total Art of Stalinism: Avant-Garde, Aesthetic Dictatorship, and Beyond, trans. Charles Rougle (Princeton University Press, 1992) whose ideas shaped contradictory attitudes towards the avant-garde.

- Nikolai Punin, Pamiatnik Tret’emu Internatsionalu, Proekt xudozhnika V.E. Tatlina (Petrograd: Otdel IZO Narkomprossa, 1921), p. 1.

- Ilya Ehrenburg, E pur se muove (Berlin: Gelicon, 1922), p. 18.

- El Lissitsky, “Basic Premises, Interrelationships between the Arts, the New City, and Ideological Superstructure” in William G. Rosenberg, ed., Bolshevik Visions, Part II (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan,1990), p. 188.

- John Elderfield, “The Line of Free Men: Tatlin’s ‘Towers’ and the Age of Invention,” Studio International, vol. 178, no. 916, November 1969. Siegfried Giedion has compared Tatlin’s tower to the spiral lantern of Borromini’s S. Ivo della Sapienza and to the figura serpentina in the mannerist and baroque architecture.

- Roland Barthes, “The Eiffel Tower,” in The Eiffel Tower and Other Mythologies (New York: Noonday Press, 1979).

- Leon Trotsky, Literature and Revolution [1924]. Quoted in Troels Andersen, Vladimir Tatlin, (Stockholm, Moderna Museet, 1968), p. 62.

- The model shown in November 1920 is discussed in the Club Cézanne where Lunacharsky, Meyerhold, and Mayakovsky debated Tatlin’s projects.

- These slogans were proposed at the First Dadaist Fair in the summer of 1920 by Grosz, Hausmann, and Heartfield.

- Vladimir Tatlin, “Iskusstvo v texniku,” in Vystavka rabot zasluzhennogo deiatelia iskusstv V. E Tatlina (Moscow-Leningrad: Ogiz-Izogis, 1932), p. 5.

- Anatolij Strigalev & Jurgen Harten, Vladimir Tatlin, Retrospektive (Köln: Du Monte Buchverlag, 1993), p. 37.

- Victor Shklovsky, “Pamiatnik tret’emu internatsionalu,” in Khod konia (Moscow-Berlin: Gelikon: 1923), pp. 108–111.

- Ibid., p. 110.

- The statue was erected by the sculptor Paolo Trubetskoi in 1909 on Znamensky Square near the Nicholas Station, now Vosstaniia Square near the Moscow Railway Station. This is how Shklovsky introduces the story: “No, not the truth. Not the whole truth. Not even a quarter of the truth. I do not dare to speak and awaken my soul. I put it to sleep and covered it with a book, so that it would not hear anything.” Ibid., pp. 196–197.

- Shklovsky, Khod konia, op. cit., pp. 196–197. For a comparative analysis of Shklovsky’s theory of estrangement, see Svetlana Boym, “Politics of Estrangement: Victor Shklovsky and Hannah Arendt” in Poetics Today, vol. 26, no. 4, Winter 2005, pp. 581–611.

- Lidiia Ginzburg, Chelovek za pis’mennym stolom (Leningrad: Sovetskii pisatel’, 1989), p. 59.

- Contemporary artist Leonid Sokov recalls that in the 1970s during the first Tatlin exhibit since the artist’s death, various elderly women who worked in the mosaic factory or in the local theaters brought with them small pictures of Tatlin’s forgotten still lives that the artist apparently gave them in exchange for money and food.

- Tatlin’s tower found echoes in another unbuilt monument of the twentieth century: The Palace of Soviets (architect Boris Iofan), which was supposed to have been built on the site of the destroyed Cathedral of Christ the Savior. In the Palace of Soviets, the dynamic and open spiral is made static, turned into a terraced colonnade and decorated with a gigantic statue of Lenin. War interrupted Stalin’s architectural ambitions, relegating the Palace of Soviets to the realm of “paper architecture.” A replica of the cathedral in concrete was built in 1998.

- The group included D. Dimakov, N. Debrin, I. Fedotov and E. Lapshina. Previous reconstructions of the tower were made in Sweden (1968), England (1971), France (1979), and USA (1980, 1983). There was another reconstruction in Russia made by T. Shapiro, once Tatlin’s collaborator, in 1975 and 1980.

Svetlana Boym is a theorist and media artist. She is the author of The Future of Nostalgia (Basic Books, 2001), the novel Ninochka (SUNY Press, 2003), and the forthcoming Architecture of the Off-Modern (Columbia University Press, 2008). She is currently working on an art project, “Nostalgic Technologies,” and finishing a book on freedom. Boym teaches in the Department of Comparative Literature at Harvard University and is an Associate of the Graduate School of Design. For more information, see www.svetlanaboym.com [link defunct—Eds.].

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.