Artist Project / Hopefuls

Want you to want me

David Levine

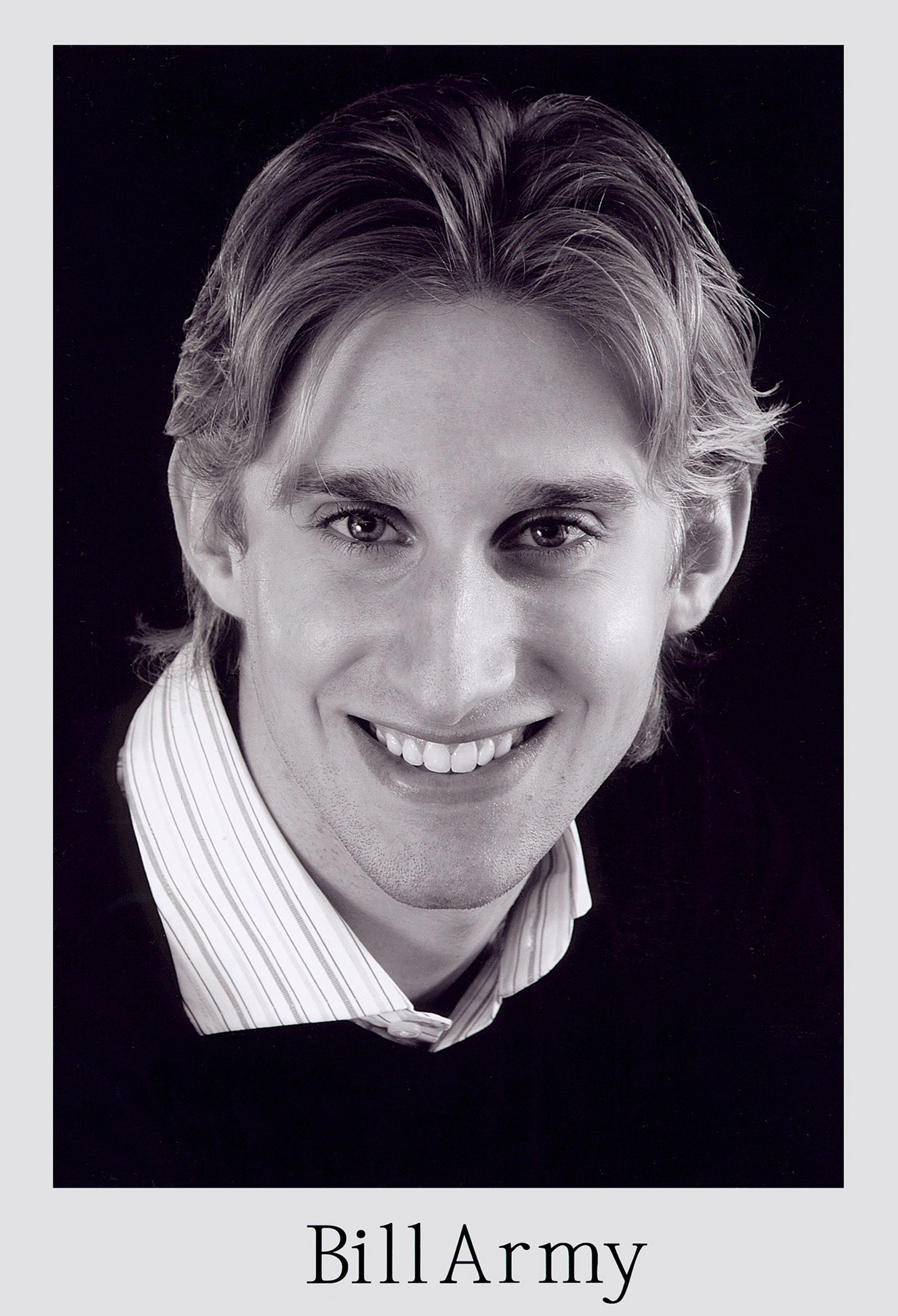

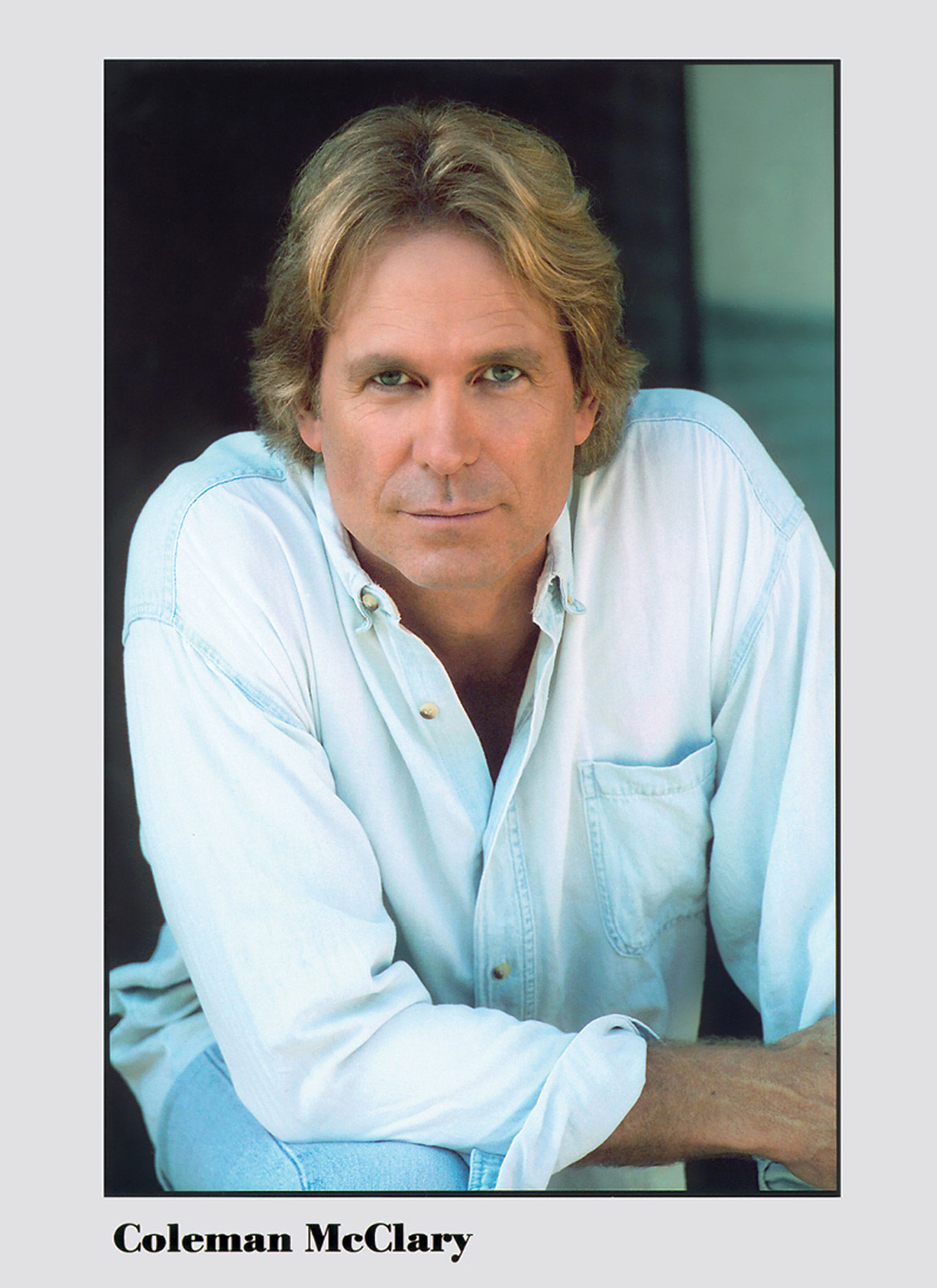

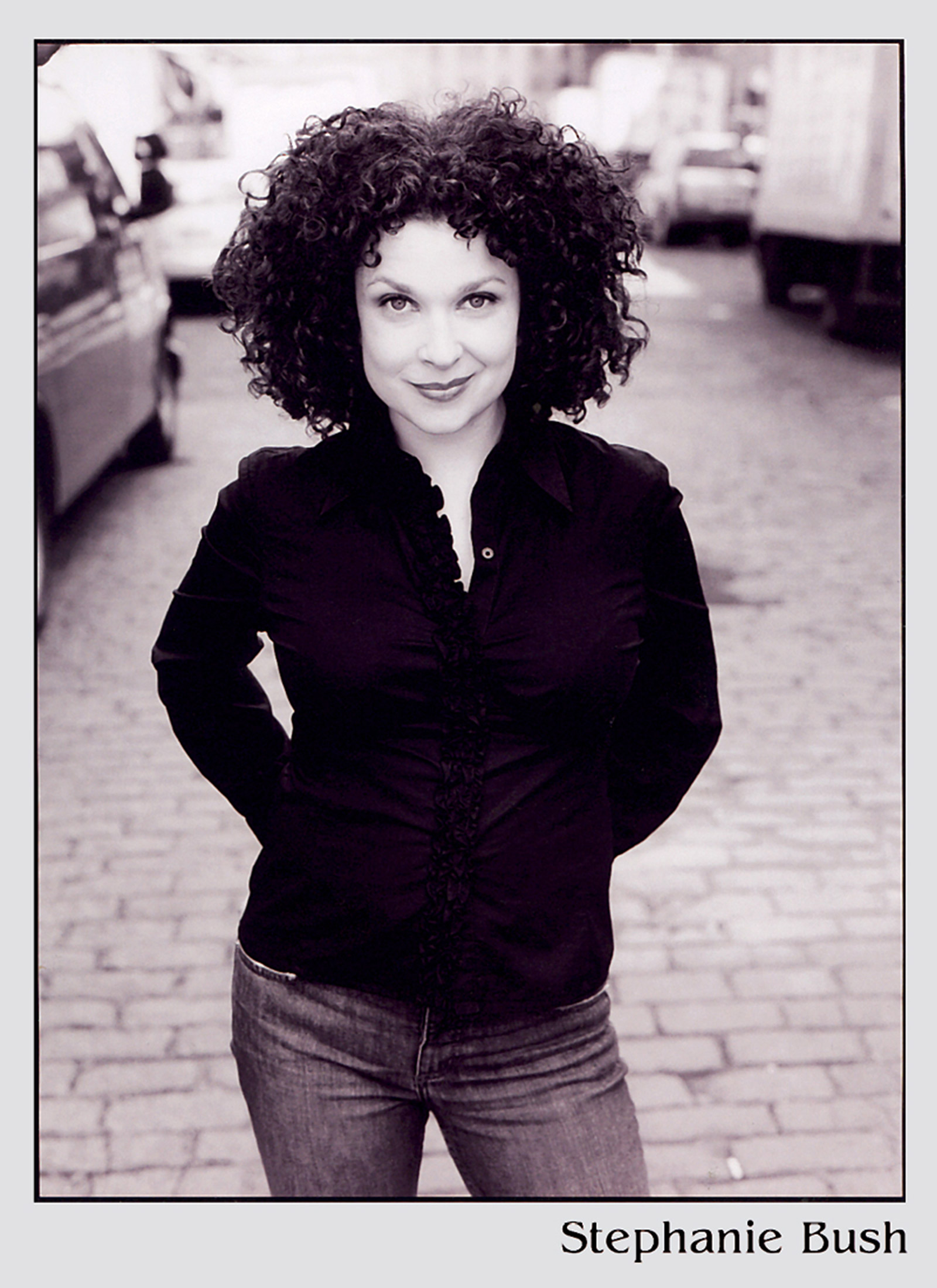

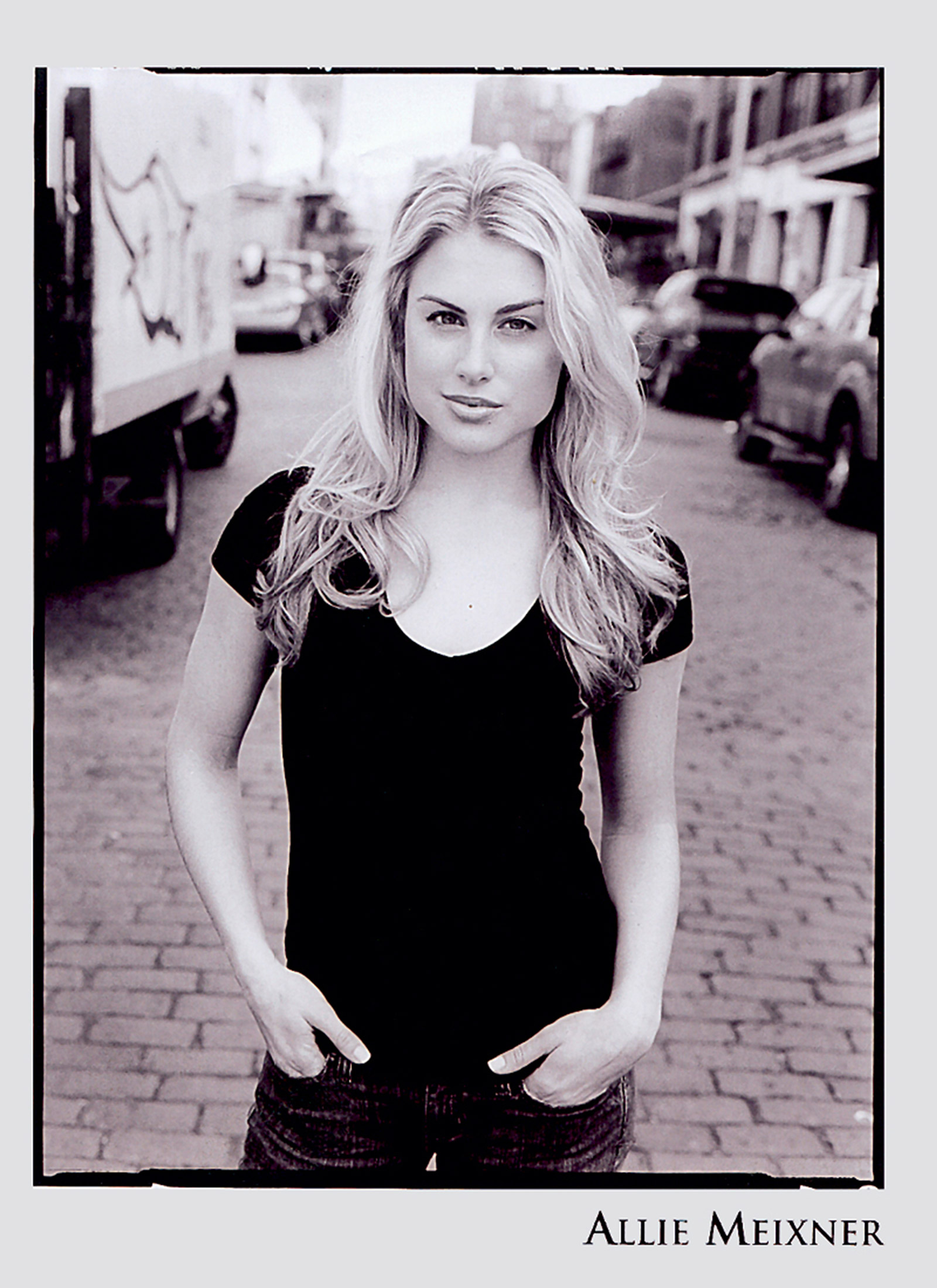

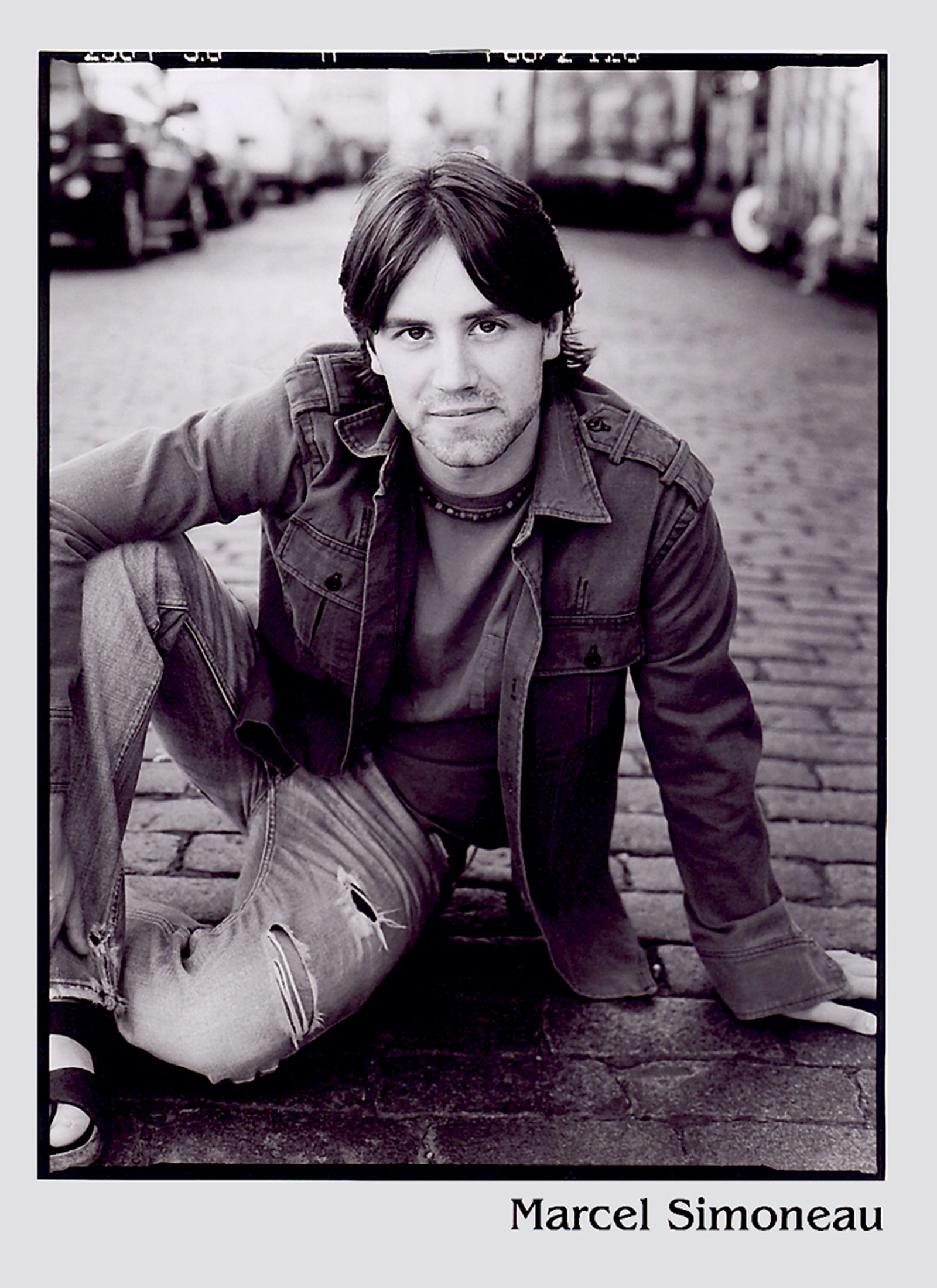

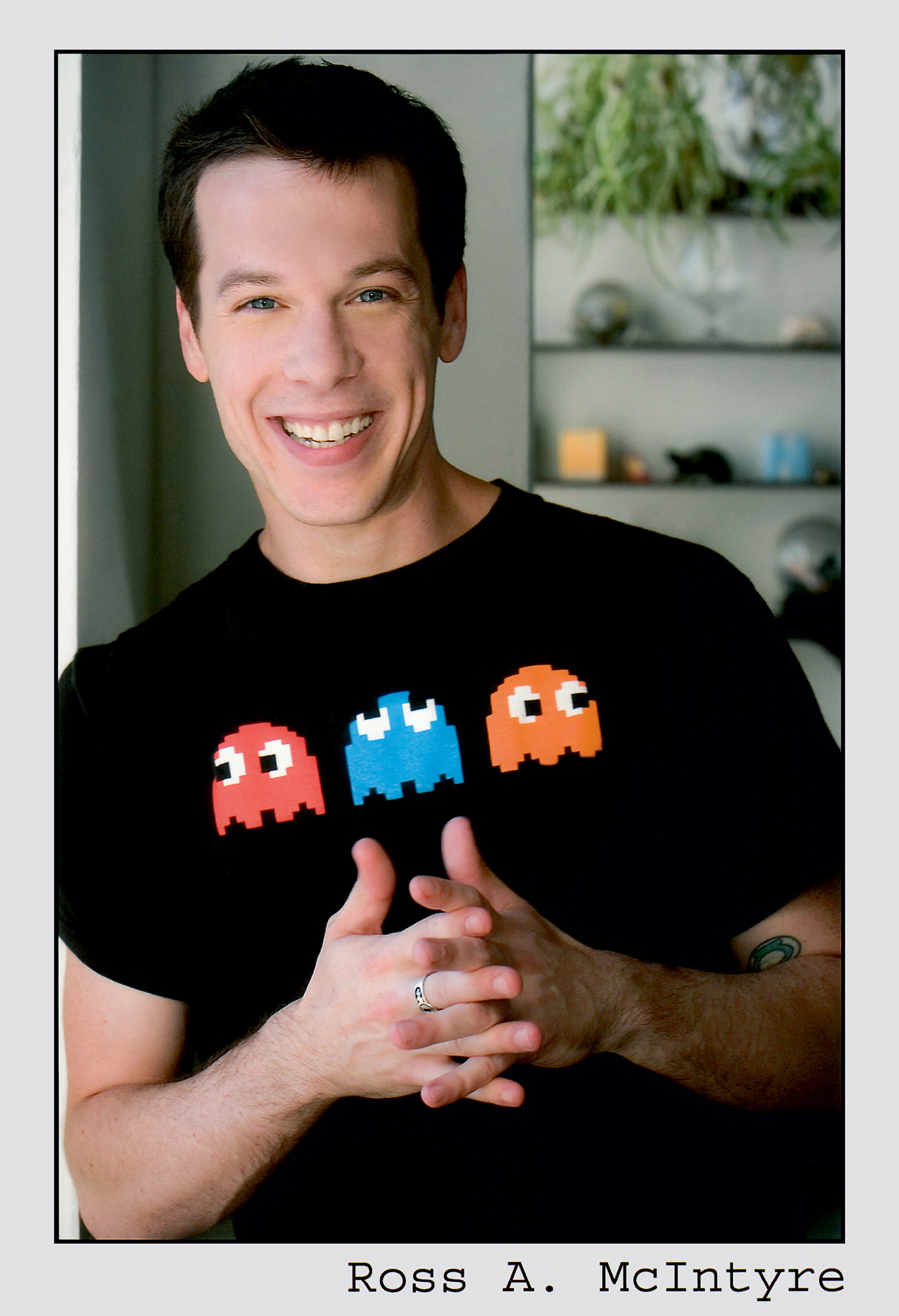

The first headshots appeared in the 1950s.[1] By headshots, I mean photographs of actors looking for work rather than publicity portraits of stars. The latter, which have been in circulation since at least the 1860s, emerged from the tradition of portraiture, and the former seem to have emerged from the latter. But clearly the headshot is not a portrait, or if it is, it’s a very particular kind of portrait. Indeed, it routinely disregards conventions of portraiture—no environment, no professional emblems, no trace of social context, and no sideways glance. The subject is always looking dead at you. This blankness, however, has nothing in common with the stripped-down psychological portraiture of the late-nineteenth and twentieth centuries, which similarly depends on empty backgrounds and forthright stares.

A better way to analyze headshots might be to consider what is there. A smile, a look, a lack of self-sufficiency you very rarely see in conventional portraiture. It is neither the smile of a celebrity sharing beatitude nor the steady gaze of the burgher or aristocrat. Instead, it is a smile that beseeches your understanding, a look that solicits your complicity, and almost always suggests, unlike a conventional portrait, that the experience is incomplete without you. The phrase that headshot photographers use for this is “the light behind the eyes.” Unlike the eyes of a portrait in a haunted house, which follow you around the room, headshot eyes fix you in place, attempting to disable your judgment with a look as titillating as it is meaningless.

These photographs need the viewer because the actors they depict are not celebrities yet. They just want to be, and your complicity is needed because “you” are the casting agent, actor’s agent, manager, or director to whom these photos are addressed. Theater scholar Meron Langsner suggests that the headshot should actually be considered a B2B marketing tool, where B1 is the actor and B2 is “the industry.” The practical and aesthetic differences between the headshot and the celebrity portrait then become clear: the latter is designed to promote a pre-existing commodity to the public, while the former is designed to market a not-yet commodity to the institutions that could accord it full status. Hence the non-specificity of the photos: whereas a celebrity portrait might show the subject in a specific role or locale, in a headshot such detail is rejected out of hand by casting agents as “too theatrical.” You could say that headshot subjects lack individuality because they have not yet been given a role; or that they suppress it in order to demonstrate their suitability for all roles.

Pick up any actor’s manual and you will find a chapter on headshots: how to shoot them, how to choose them, and where to send them. Indeed, headshot photography comprises an entire industry ancillary to entertainment. An actor will, on average, spend $1,180 each year on photo sessions, prints, and mailings. An agent receives between thirty and sixty unsolicited submission envelopes per week, depending on the size and prestige of the agency. These contain between one and three headshots, depending on how many “looks” the actor wants to show the agent. According to Ross Reports, the mailing list bible for actors, there are seventy-nine agencies in New York City, each employing between one and twelve agents, which means that during any given week there are roughly ten thousand headshots circulating through the city. This represents 4.8 tons, and roughly 5,700 acres, of photo paper per year—enough to bury the streets of Manhattan’s theater district to a depth of six feet. Ninety-nine percent of these submissions are perfunctorily thrown out; the remaining 1 percent are put on file and occasionally get the actors an audition and, in very rare cases, a job.

My own archive is culled from the discards, which I catalogue according to pose, paper quality, postage, font style, cover letter etiquette, and other criteria, some more subjective than others. This archive is part of a larger project of tracking, and ultimately memorializing, unsolicited submissions across the entire cultural field. The Culture Industry does generate waste. What’s the ecological impact of this rejected material? How much money is lost in its production? How much waste—trashed image CDs, demo tapes, slides, and manuscripts—does the industry need to generate in order to maintain its meritocratic reputation?

Of course, unsolicited material must be thrown out—there is too much of it, and the cultural gatekeepers have no choice. And of course it makes everyone feel awkward: when you send in your unsolicited slides, poems, or headshots, they become tools for scaling a wall, in the hope that, once on the other side, they can go back to being your art, writing, or face, though in a transcendent new way. In the moment of rejection, however, the submission is forever frozen in a state of mere instrumentality. From the trash, it stares up at you hopefully—unsolicited, and still soliciting.

- This is according to Meron Langsner, whose unpublished paper “Personal Icono-graphy, the Business of Making Art, and Art for Doing Business: The Actor’s Headshot and its Place In and Out of the Theater World, An Overview” is the only critical treatment of the subject I have come across.

David Levine works in theater and visual art. His installations, videos, and performances have been seen at the Sundance Theater Lab, Gavin Brown@ Passerby, Galerie Magnus Mueller, and Documenta XII (with Cabinet). He is the recipient of a Kulturstiftung des Bundes grant for Bauerntheater (2007) and an Étant Donnés Grant for Venice Sav’d: A Seminar, which will premiere at P.S. 122 in March 2009. Portions of his archive of headshots, featured in this issue, will be exhibited in 2009 at Galerie Feinkost in Berlin.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.