Studies in Classic American Literature by Rita Kamins

Reading with my mother

Josh Kun

The reader became the book…

—Wallace Stevens

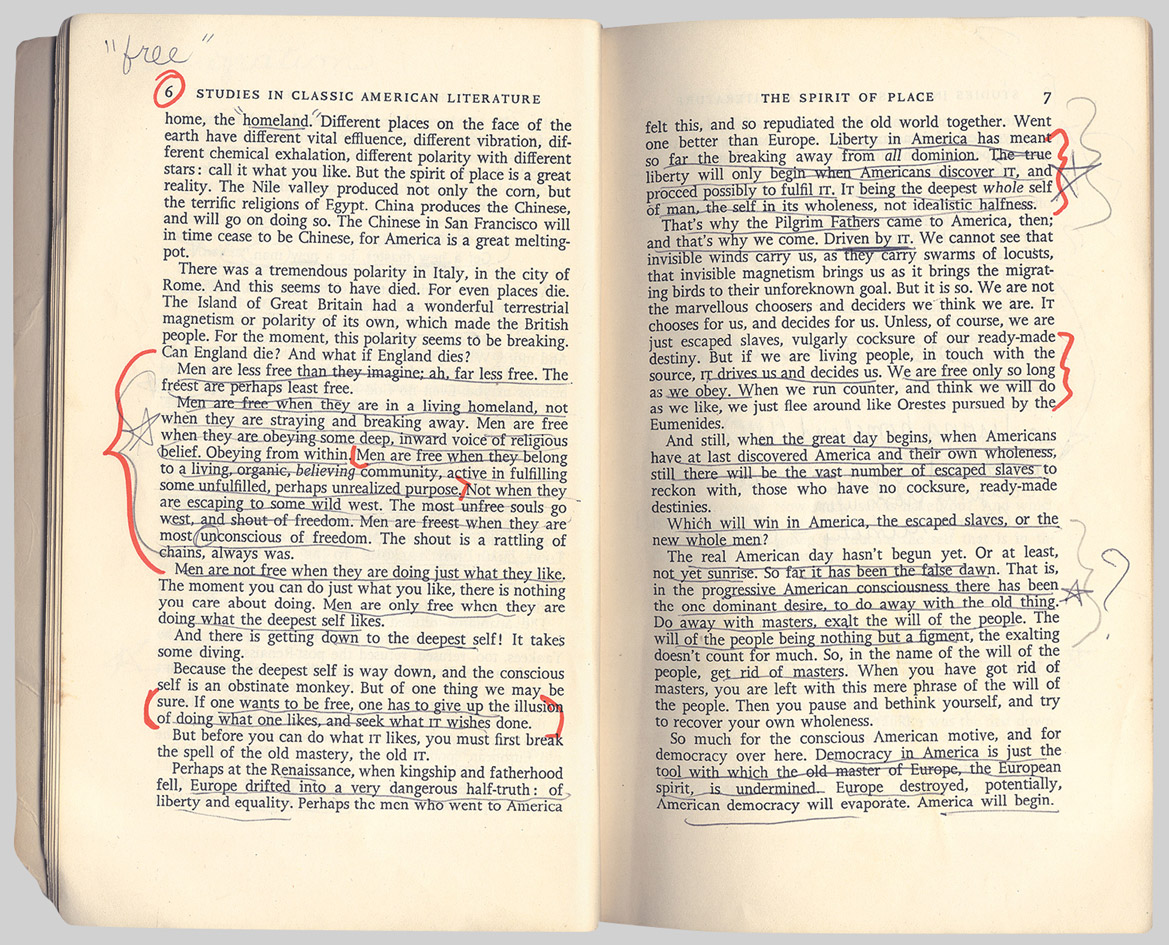

The book has 177 pages of which my mother read 21. They are the only pages that are marked, and they are marked vigorously, in black ballpoint pen, red marker, and pencil, in a personalized code of underlines, double underlines, triple underlines, five-sided stars, circled words and phrases, brackets, braces, arrows, and margin notes. The markings are traces of her interaction with the text. They are her rewrite of Lawrence.

Lawrence’s foreword ran for nearly two pages. This is my mother’s version:

But equally no good asserting him merely … Because all that is visible to the naked European eye, in America, is a sort of recreant European. We want to see this missing link of the next era. … So the only thing to do is to have a look for him under the American bushes. The old American literature, to start with … Some insisting on the plumbing, and some on saving the world: these being the two great American specialties. … You can’t save yourself before you are born. … Two bodies of modern literature seem to me to have come to a real verge: the Russian and the American. … The European moderns are all trying to be extreme. The great Americans I mention just were it. Which is why the world has funked them, and funks them today. The great difference between the extreme Russians and the extreme Americans lies in the fact that the Russians are explicit and hate eloquence and symbols, seeing in these only subterfuge, whereas the Americans refuse everything explicit and always put up a sort of double meaning. … subterfuge ...

She was eighteen when she read Lawrence and this is what she found important. This is what she decided she should know, what she decided was valuable about what he’d written. It’s as close to a portrait of her as a young adult as I will ever get, her mind revealed in marginalia.

When we read books that have been underlined, it’s hard not to read them as the reader did. As much as we may resist it, our eyes naturally skip over the original typesetting and focus on the underlined sentences and words. We make instant jump cuts. We are drawn into unconscious remixes. When I read this copy of Lawrence, I read my mother reading him. There is no way for children to truly know their parents, but this might be a place to start—a locked diary rescued from beneath a mattress, a incomplete codex never meant for anyone else to see.

I am not reading D. H. Lawrence. This is Studies in Classic American Literature, written by Rita Kamins in the fall of 1965.

Adler doesn’t trust people who labor under a “false reverence for paper, binding, and type” and kowtow to an author’s genius. Who wants to go through life without getting things dirty, without leaving a trace? Reading is a conversation and if you don’t mark your book, you are not adding much to it.

That’s the premise of most marginalia buffs, who are pretty sure that Roland Barthes copped his “Death of the Author” idea—once the reader reads, the author stops being the author—from all those anonymous and everyday eighteenth- and nineteenth-century readers who scribbled in the margins with fever and conviction. For every Samuel Johnson publishing a celebrated Plan of a Dictionary of the English Language in 1747, there was an average reader like Samuel Maude who thought so much, or so little, of Johnson’s book that he used its margins to keep an elaborate personal diary. His curling, swooping handwriting dwarfs the printed type, urging you to read Maude, not Johnson.

In Marginalia, H. J. Jackson’s study of the Samuel Maudes of the world (in an inevitable irony, my library copy is spotless), he divides the history of marginalia into three “kingdoms” of authorial defacement: the Kingdom of Competition (up to 1700), the Kingdom of Sociability (1700–1820), and the Kingdom of Subjectivity (1820–present). For Jackson, it’s what happens in 1819 that really tips the scales: Samuel Coleridge admits that he too marks up books and publishes a whole volume of his writings in other people’s books to prove it. This forever changed the cultural capital bestowed on the margin scribe. Readers were writers, writing in books was a subjective act of creation and intellectual dialogue, and Coleridge was as tempted by blank parchment inches as any other mortal.

As for my mother, squarely in the Kingdom of Subjectivity, she was rewriting Lawrence, who was rewriting eighteenth- and nineteenth-century American writers like Benjamin Franklin and Herman Melville. Studies in Classic American Literature may have been published as its own book, but wasn’t it really just a more formal version of Lawrence’s own marginalia in books by Franklin and Melville? Surely Lawrence was a beefsteak guy. In Studies, Lawrence famously has a field day with Franklin’s stiff-upper-lip list of virtues (Temperance, Moderation, Chastity), countering with his own guide to better American living—“Eat and carouse with Bacchus,” “There are many Gods,” “Follow your passional impulse.” Surely, Lawrence would have filled the pages of Franklin’s autobiography with angry scribbles and outraged exclamation points.

Of the two lists, my mother liked Lawrence’s virtues. She didn’t mark Franklin’s list, but starred Lawrence’s three times, drawing a curved arrow from top to bottom to make sure she re-read all of them. That she would choose Lawrence over Franklin is surprising. The mother I know now is no friend of Bacchus, no yoga mat polytheist, and gave up on the “passional” impulses of experience after a bout with leukemia turned her into a careful, guarded taster of life’s offerings.

“The world fears a new experience more than it fears anything,” she underlined. “Because a new experience displaces so many old experiences.” Lawrence was showing her who she would soon be: a protector of old experiences, a reluctant adaptor, a friend of fear.

But it’s nice to know that at eighteen, Lawrence’s vision of America still looked damn good, even to a girl who would grow up not to drive freeways and only like movies shot in the bright, smiling sunshine of friendly daylight.

She thought about that line, and then thought about it again, and again, and again, until it became a part of her, until the words were hers.

She used to have a soft spot for historical novels and biographies, especially anything Teddy Roosevelt, anything Aztec or Mayan. Before she had us, there were archaeology dreams, visions of a life of digs and pith helmets, baked crumbling hillsides that when sifted revealed lost worlds. She held on for a while, leading grammar school field trips to California canyons rich in ancient sediment—the basement is still full of flaking mollusk shells and cracked tusks filed delicately in plastic cases meant for action figures— and then volunteering as a tour guide at the La Brea Tar Pits.

My mother, the saber-toothed tiger. My mother, the ground sloth. My mother, the dire wolf. My mother, the mammoth rising from the sticky black sea alongside Wilshire Boulevard. I always figured the books were prosthetics for the amputated limbs of deferred archaeological dreams, turning paper not dirt, handling spines not fossils, excavation time-travel undertaken from the comfort of an armchair with a cup of hot Earl Grey tea and a paper towel sprinkled with almonds and Hershey’s kisses.

There are no more beefsteaks. If reading was once her way of living vigorously, what happens when the books stay closed?

You can’t save yourself before you are born, she underlines, but you can after you are born.

This is where her marginalia starts to get me down.

She was most intrigued by Lawrence’s interest in the question of America’s political, cultural, and literary independence from the yoke of Europe. “Whatever else you are,” Lawrence wrote, “be masterless.” My mother underlined it and starred it, and when Lawrence quotes Caliban’s refrain from The Tempest (“Ca Ca Caliban / Be a new master, be a new man”), she underlined new and circled master. She was taken by Lawrence’s feverish attachment to a pure, true freedom and brought out the red marker for his declaration, “Men are free when they are in a living homeland, not when they are straying and breaking away.” There is red for his riff on “escaped slaves” versus “new whole men,” red for his idea that American liberty is really synonymous with breaking away from the dominion of Europe, red for his fantasy of some “deepest whole self” just waiting to be discovered in the confused American soul. Then, in the midst of Lawrence’s critique of Franklin, there is red for my mother’s own margin notes: free to do only as soc. wishes “fenced in” restricted freedom is contradiction.

Why this interest in freedom? My mother was a daughter in the midst of leaving home and in the throes of reexamining her relationship to her own masters, her parents. They may not have been from the Old World of Europe and she was certainly not one of Lawrence’s “escaped slaves,” but her masters were from the wide-open flats of North Dakota, a strange planet of farmhouses, general stores, barn dances, and sunflower harvests that couldn’t have been further removed from her life as a girl in 1960s Los Angeles. Her mother was a former nurse and high school basketball player with a soft spot for romance novels. Her father owned a men’s clothing store with its own putting green and kept the Dakotas alive in his mind by devouring Louis L’Amour paperbacks like only a Russian Jew from the Badlands could. How to leave them without leaving them? How to be masterless and still be able to go home for spaghetti marinara and clean laundry?

More than anything else, America was like a child seeking freedom. “Like a son escaping from the domination of his parents,” Lawrence wrote and my mother underlined. “The escape is not just one rupture. It is a long and half-secret process.” Children never escape their parents. It is indeed a long and half-secret process.

Lawrence treats eighteenth- and nineteenth-century America as a literary son, but as more than one scholar has pointed out, America was more of a literary daughter. Perhaps the difference stems from whom Lawrence focuses on—writers, not readers. In her wonderful history of the American novel, Revolution and the Word, Cathy Davidson emphasizes that it was not only writers who wrote America into cultural independence. The readers of their novels—and especially all those who wrote in the margins—also helped shape the character of the emergent republic through their judgments and opinions.

The eighteenth century witnessed a shake-up of social hierarchies, thanks in large part to the rise of the American novel. By reading books and writing in them, common readers fought their own war for egalitarianism and democracy. The most common of common readers were women, so much so that the threats the novel was believed to pose to the ruling order of America were very often seen as female—women reading and commenting their way into the boys’ club of nationalism, shaping themselves as literate subjects. The threat they posed was quickly met with the invention of a gendered pathology: “Novel Reading, a Cause of Female Depravity” as an 1802 diatribe put it. “I have seen two poor disconsolate parents drop into premature graves,” it read, “miserable victims to their daughter’s dishonour, and the peace of several relative families wounded, never to be healed again in this world.”

My mother saw herself in Lawrence’s America. A daughter facing her own independence from her parents’ mastery, had she also become one of Davidson’s readers, two centuries too late, a daughter afraid of dishonor?

These are the questions I want to write in the margins of her margins, but I resist. I remember what she underlined in the foreword: “The great difference between the extreme Russians and the extreme Americans lies in the fact that the Russians are explicit and hate eloquence and symbols, seeing in these only subterfuge, whereas the Americans refuse everything explicit and always put up a sort of double meaning … subterfuge.” If my mother reads this essay, she will undoubtedly get Russian on me. She will accuse her son of eloquence and symbolism. She will cry subterfuge. It would be the same war of independence, the Russian parent and the American child tussling over words.

Josh Kun is the author of Audiotopia: Music, Race, and America (University of California Press, 2005) and co-author of And You Shall Know Us by the Trail of Our Vinyl (Crown, 2008), an album cover history of Jews in America. He is a professor in the Annenberg School for Communication and the Department of American Studies and Ethnicity at the University of Southern California.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.