George R. Lawrence, Aeronaut Photographer

Above the ruins of San Francisco

Christopher Turner

On 18 April 1906, at 5:12 am, San Francisco was hit by an earthquake that is estimated to have been 8.25 on the Richter scale. The earth shuddered for a full minute and—as chimneys fell, gas pipes burst, and electrical circuits shorted—fires broke out all over the city. These were far more devastating than the quake or its aftershocks. The city’s subterranean water system was so badly damaged that there were few resources with which to fight the flames. The fire department dynamited whole rows of buildings to try and create firebreaks, and created more fires in the process. Several firestorms joined together in one great inferno that blazed for three days; 490 city blocks were razed and over 250,000 people were made homeless. Almost two-thirds of the city was destroyed.

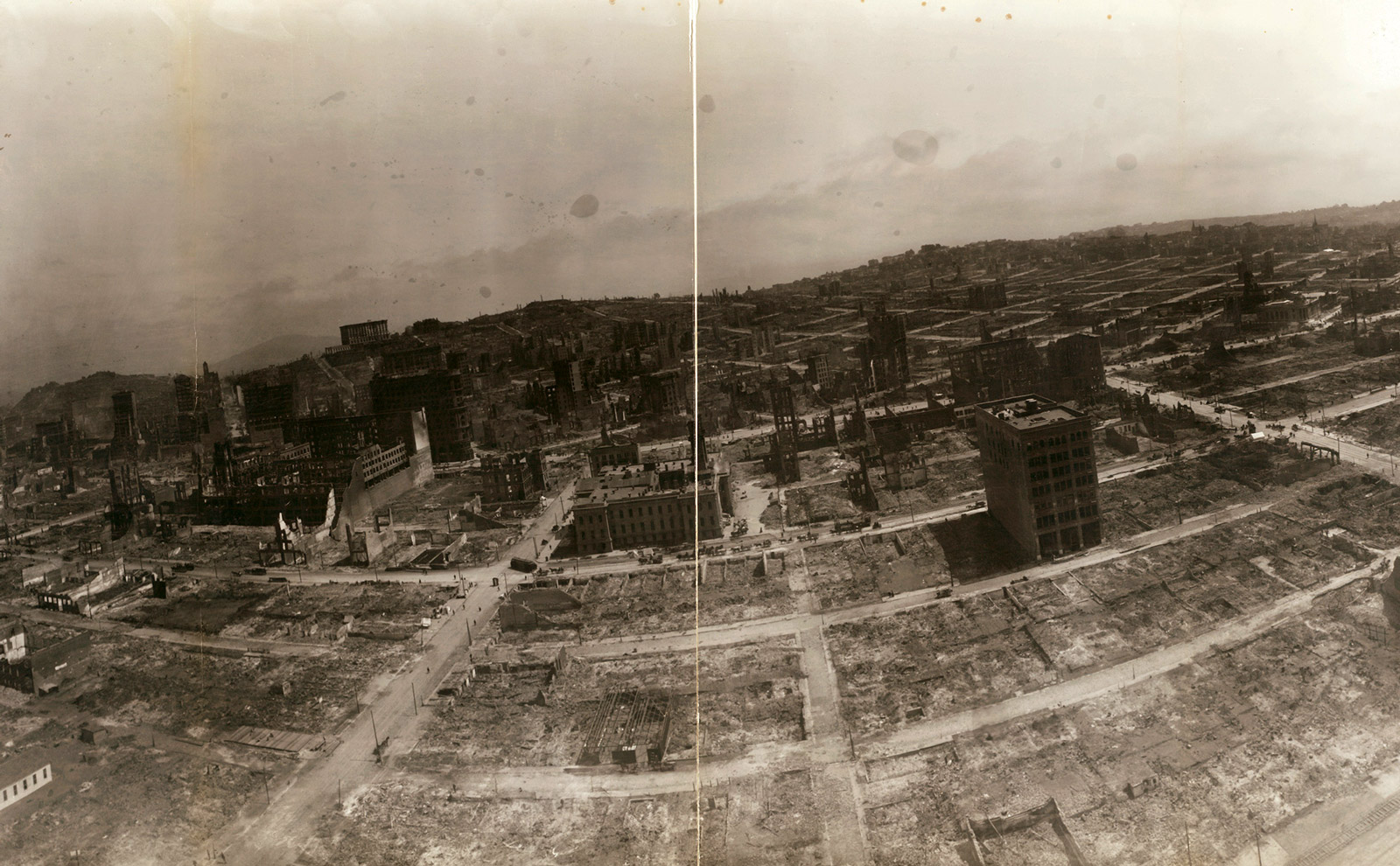

The extent of this devastation was captured in an iconic photograph, San Francisco in Ruins, taken six weeks after the fires burnt out. Shot from 2,000 feet in the air, the 160-degree panoramic image shows a view of the city from Ferry House to Twin Peaks, ten kilometers inland. The signage on the waterfront is clearly visible, and you can make out figures amidst the masonry-strewn ruins. The flattened city looks like a ploughed field, the streets shiny furrows that have thrown up black ridges of charred wreckage. The sun’s rays emerge from behind a cloud over the mouth of the San Francisco bay, sparkling the water with glowing light, almost as if to hint at new beginnings.

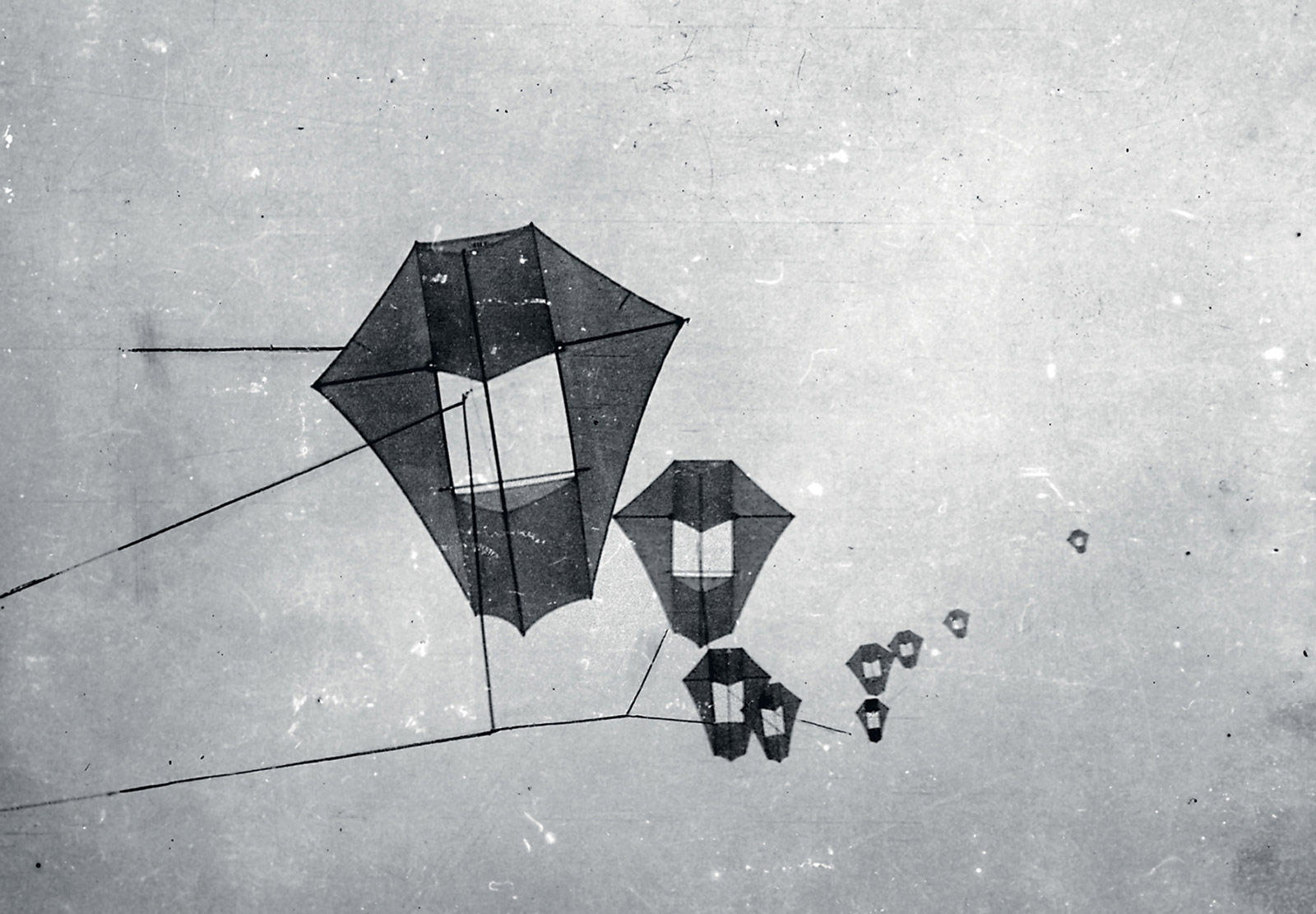

The photograph was taken by George R. Lawrence, using what he describes, in an inscription on the enormous 48 x 183⁄4 inch print, as a “Captive Airship.” The image was deemed by many to be a composite fake. Manpowered flight was still in its haphazard infancy (the Wright brothers were granted a patent for their Flyer only six days before Lawrence took his photo), and, though Nadar had shot Paris from a hot air balloon in 1868, the even lighting in Lawrence’s aerial view of San Francisco placed its author under suspicion. The fact that Lawrence claimed to have taken his picture from a boat with a camera that had been fastened to a series of kites did nothing to reassure the skeptics.

Lawrence had a photographic company in Chicago whose slogan was “The hitherto impossible in photography is our specialty.” He had earned the nickname “Flashlight Lawrence” because of his pioneering work with magnesium flares—experimentation that, according to an obituary published in 1939, caused “numerous explosions which burned off his hair, eyebrows, and mustache, and burst his eardrums.” His ingenious solution to these problems was a system that released a canvas bag over the discharged lighting apparatus so as to extinguish any fires and contain the smoke, allowing him to shoot indoor scenes without choking or setting fire to his subjects. He was hired to take panoramas of political conventions, legislative sessions, and festive occasions, to which he gave titles such as “Secretary Taft’s Philippine Party Dinner.”

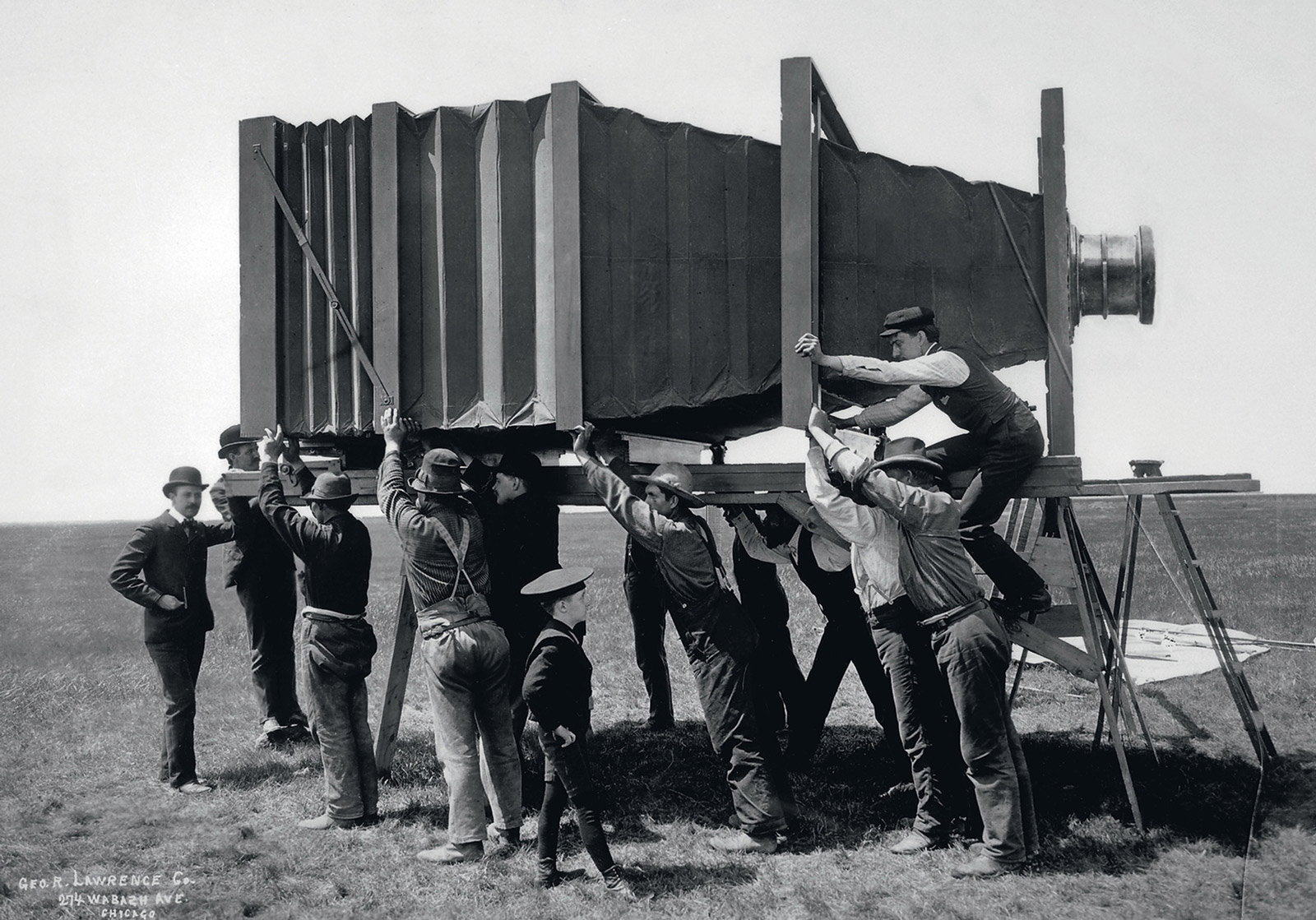

Lawrence was also famous for having created what was billed as “the world’s largest camera.” It cost $5,000 to make, weighed 1,400 pounds, had twenty-foot bellows, and required fifteen people to carry it. One picture of Lawrence shows him with a lens cap the size of a garbage can lid under his arm, timing the exposure of his gargantuan device. The oversized camera was commissioned to create an 8 x 41⁄2 foot photograph of the Alton Limited, a sleek passenger train that had recently been built to run the Chicago to St. Louis line. The resulting print, promoted as The Largest Photograph in the World of the Handsomest Train in the World, was exhibited at the Paris Exposition of 1900 and, like the later image taken by his kite camera, was judged a patchwork fake. The French Consul General was sent from New York to Chicago to verify the photograph and, after he’d inspected the camera and enormous glass plate, Lawrence was awarded the “Grand Prize of the World for Photographic Excellence.”

The photographer continued to innovate, challenging himself to perfect aerial views of urban scenes, such as racetracks and ballparks. He invented a telescoping tower that could lift him up to 200 feet, before customizing gas-filled hot air balloons to get bird’s eye views from five times farther up. On 20 June 1901, Lawrence was almost killed while photographing the Chicago Union Stock Yards from the air. His balloon broke free of its anchor in heavy winds and floated off over Lake Michigan. He had built a special platform to replace the traditional basket, so as to obtain an unobstructed view, and this suddenly gave way: he fell 230 feet. Lawrence survived only because his fall was broken by telegraph and telephone wires; according to his obituary, the experience “(temporarily) cured him of further use of balloons to get spectacular views.”

When Lawrence saw a kite trailing an advertising banner over Chicago, he imagined a less risky way of obtaining lofty perspectives. He began using trains of up to seventeen kites to lift a forty-nine-pound panoramic camera that he specially adapted for the purpose. Unbeknownst to him, a precursor to this device had been built twenty years earlier by French inventor Arthur Batut, who shot a series of aerial views of La Bruguiere in southern France with a kite camera. Batut had used a slow-burning fuse to trigger the camera’s shutter; Lawrence set his off with an electrical current transmitted through the metal kite line (like Benjamin Franklin, but backwards). A small parachute would be released to indicate that a picture had been taken, and Lawrence hauled down the kites so that the camera could be reloaded.

Nadar’s aerial photography had attracted the attention of the French military; Lawrence’s kite images were also thought to have possible wartime uses. In August 1905, at President Theodore Roosevelt’s personal recommendation, Lawrence was invited aboard the USS Maine to demonstrate his system as a possible reconnaissance tool. Because of high winds, the results of these military tests were mostly blurred, and Lawrence did not get the sum that he wanted for his invention, but the lengthy report on the trials is an invaluable document in explaining the camera’s workings.

To take his panoramas of San Francisco, as the navy report illuminates, Lawrence stabilized his bulky camera with three fifteen-foot-long bamboo poles attached to its sides (these had to be cropped off or retouched out of the corners of his pictures); from each of these a 120-foot silk cord was hung, and these joined together to support a three-pound weight that helped prevent the camera from swaying in the wind. The camera had a nineteen-inch focal length, and the impressive depth of field was achieved by having the camera’s shutter taper from half an inch at the bottom to four inches at the top, so that when the lens swung through its 160-degree arc the murkier distance was exposed for eight times as long as the brighter foreground.

Lawrence sold his spectacular pictures of the earthquake wreckage for $125 a copy; in total, he made $15,000. After an expensive trip to Africa, where he tried to take panoramas of animals in their natural habitat from balloons and to flashlight lions—who, instead of running away, attacked and destroyed several precious cameras—Lawrence gave up photography in order to concentrate on aircraft design. He started a company that built “enclosed-cabin flying boats,” wooden seaplanes that resembled Zeppelins with wings. Lawrence soon held patents for over a hundred inventions relating to airplanes.

It is fitting that Lawrence made this career change from aerial photography to aeronautics. Nadar, the photographer he emulated but never met, set up the Society for the Encouragement of Aerial Locomotion by Means of Machines Heavier than Air (which had Jules Verne amongst its members), founded the newspaper L’Aéronaute, raised money for research into flight by giving rides in his balloon, and exhibited early flying machines in his studio. “Man will fly like the bird,” Nadar promised, “better than the bird; for … it is certain that man will be obliged to fly better than the bird, in order to fly merely as well.”

Christopher Turner is an editor of Cabinet. His book, Adventures in the Orgasmatron: How the Sexual Revolution Came To America, is forthcoming from Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.