Iron Ivy

The picturesque charm of the American fire escape

Thomas A. P. Van Leeuwen

America’s exterior fire escapes hang on old and decrepit buildings in inner cities, on residential and commercial buildings, on low and tall buildings, and even on early skyscrapers. Countless at the turn of the twentieth century, their numbers have now been greatly reduced. In 2004, the New York Times reported: “No one is sure exactly how many fire escapes are left; Vincent J. Dunn, a retired deputy chief with New York City’s Fire Department, guesses there may be 200,000” in New York City.[1] They are more likely to be found in the less affluent parts of New York: West Side Story, for example, was set on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, a neglected tenement district in the late 1950s when the film was made.

As in West Side Story, the fire escape stands for something else, something more romantic, a balcony, or even a “box seat,” as one of Inwood’s residents calls it.[3]West Side Story, a 1957 Broadway musical made into a Hollywood film in 1961, was so heavily identified with the architectural environment in which it was set that a few schematic flights of stairs from a fire escape became its unmistakable logo.[4] Even today, when the fire escape is disappearing from our memories, posters announcing new stage productions of West Side Story still use the same iconic image of three flights of black iron stairs set against a red background.

Stairs and balconies are viewing platforms, lookouts onto the world, and West Side Story cleverly replaced Romeo and Juliet’s noble balcony with a fire escape tête-à-tête between working-class Tony and immigrant Maria. But despite the insecurity and deprivation represented by the setting, the romance was the same, better even—stronger and charged with a more acute sense of escape. Of course, fire escapes are also meant to help you escape a building in case of a fire. But even that was not always as self-evident as it might seem.

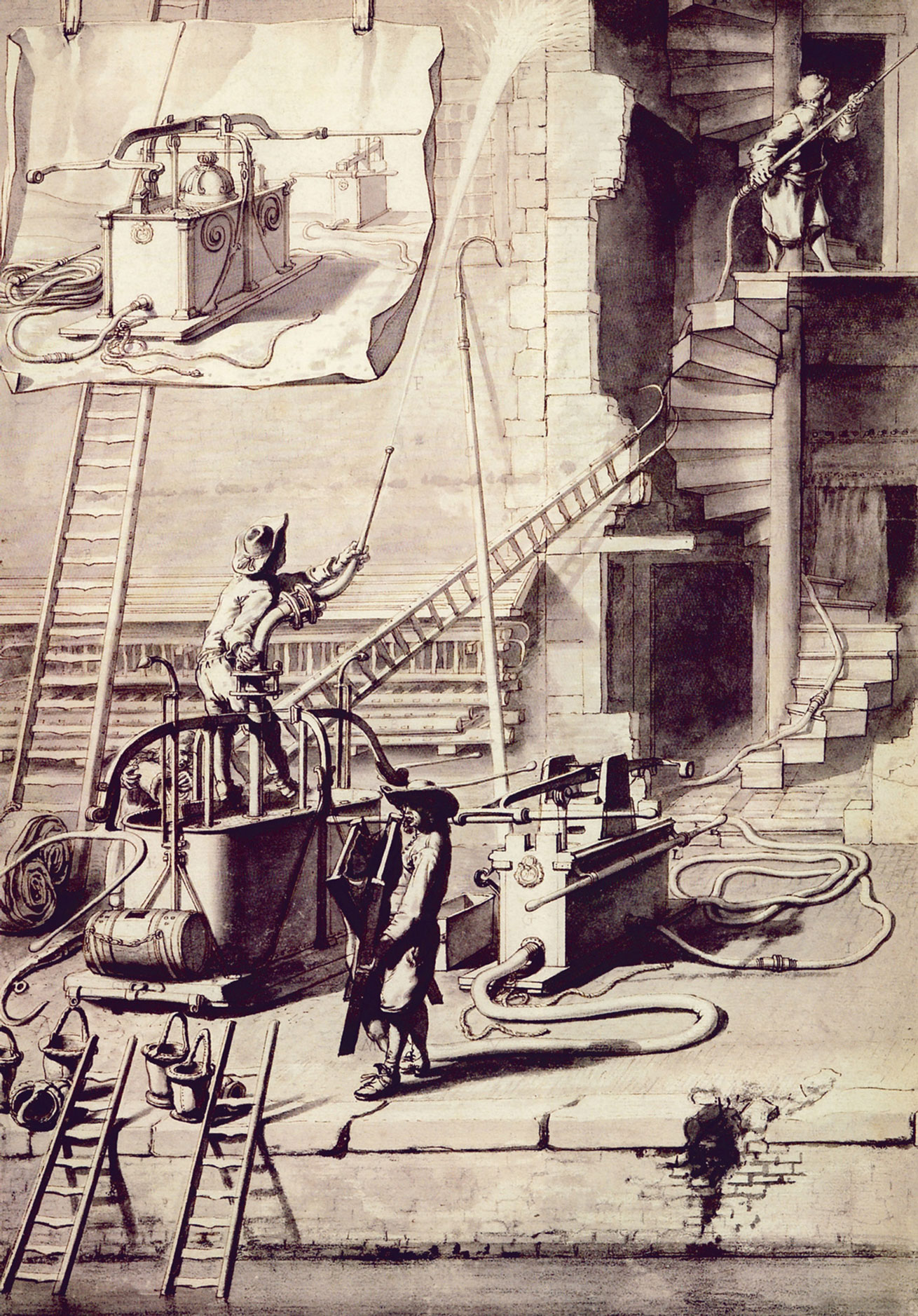

Mobile fire escapes were, however, risky contraptions. Climbing them was the work of professionals, and civilians, even in times of utmost desperation, balked at trusting their lives to such apparently unstable structures. Victims of a fire instinctively climb to the highest point in an effort to remain ahead of the increasing smoke and heat. The roof—typically reached through a hatch or “scuttle”—would be the nearest point of relief, but also the last.[6] When a building catches on fire, the first thing that burns is the staircase. Made of wood and designed to connect the various floors, staircases act like fast-burning fuses. Meanwhile, the roof of a burning building is akin to the top of a funeral pyre; the hottest and smokiest spot available. Nevertheless, picking up refugees from the roof was the motivation behind establishing London’s mobile fire escape brigades. Their escape ladders had to be constantly refigured to keep up with the ever-increasing heights of buildings, a progression that finally reached its limit with the advent of tall, steel-framed buildings in the late nineteenth century.

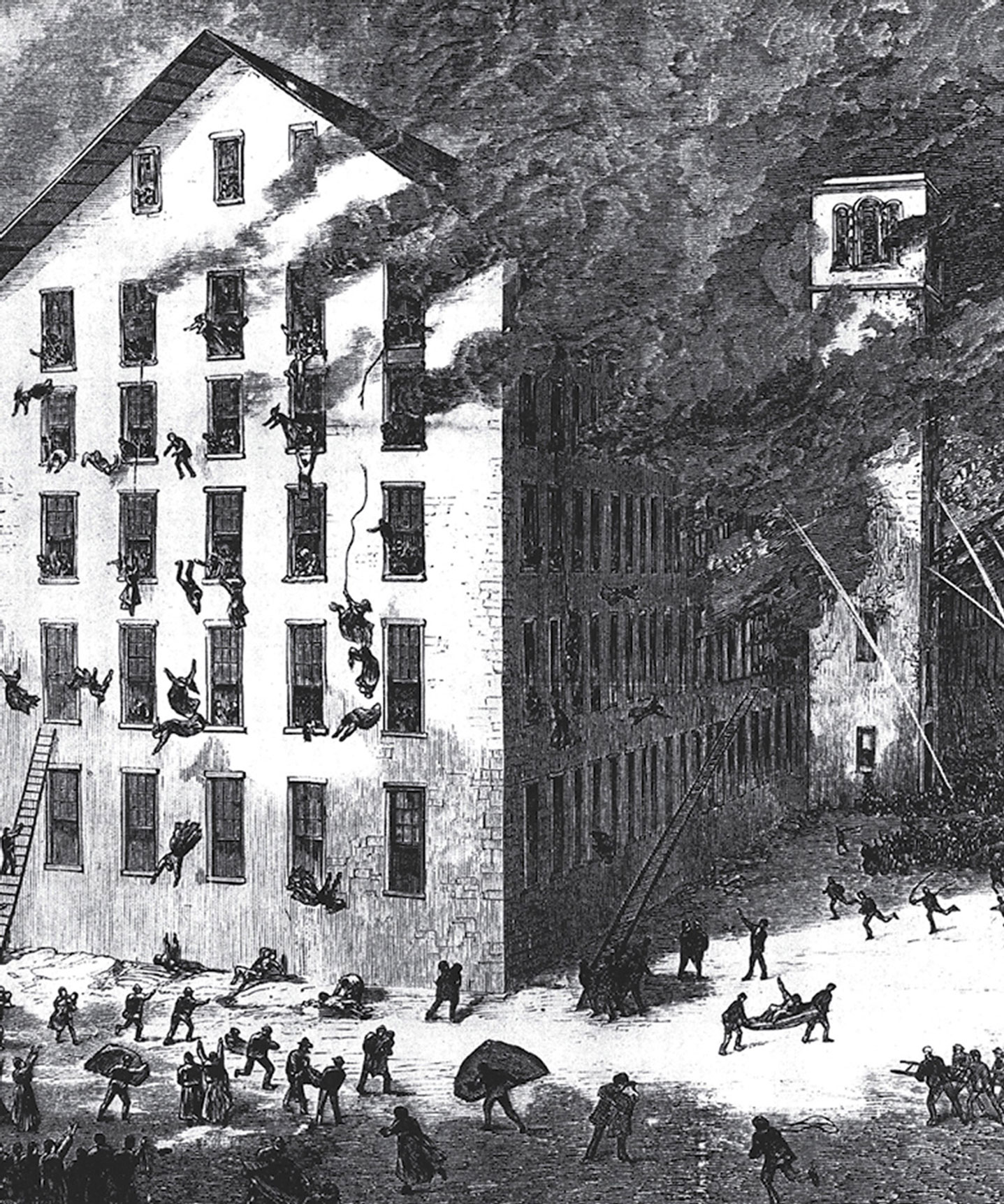

At that point, victims in tall buildings on both sides of the Atlantic were left no other choice than to jump. This was dramatized most poignantly in the 1874 fire at a textile mill in Fall River, Massachusetts, which shocked a nation that learned of the events through dramatic woodcuts, published by magazines and newspapers, of desperate victims jumping out of windows. Finding the general stair tower blocked and firemen’s ladders too short to even reach the second-floor windows, workers at the cotton mill tried to escape the flames by jumping out of fourth-floor windows. Twenty-three died; many more were permanently injured. The factory’s printmaker did his best to catch the jumpers by hovering under their final destination on the pavement. Such acts of “defenestration” signal, of course, that the victim chose death by falling over death by incineration. It is small consolation that most victims of a fire are killed by smoke rather than the fire itself, and that jumpers often experience a fatal heart attack before they hit the pavement.

The Fall River disaster naturally resulted in an ongoing national investigation into other means of egress. Many ingenious solutions were proposed, ranging from ropes and derricks (such a thing was fitted on the balcony of the White House for the obese American president Taft) to textile chutes, nets, inflated cushions, parachutes, and many other more or less daring precursors to human flight. In the end, the only realistic approach remained a fixed, external fire escape, made of iron balconies and interconnecting stairs. Originally, the stairs were vertical ladders, but gradually, starting with recommendations made in 1885, they acquired a more comfortable angle for descent. The horizontal fire balcony, made of iron and consisting of a platform and railings, was bolted to the building and supported by iron braces. Victims of fire no longer had to wait for firemen to rescue them.

Official reports of great fires counted property losses, not human casualties. Warehouses were normally better constructed than tenement blocks, and fireproofing was first applied to factories and storage facilities. “Thus, again and again, in town and country alike, Americans encountered the disturbing scent of burnt money. And yet, although an overview of the ‘great fires’ helps to establish the dimensions of the problem, the preoccupation with statistics almost trivializes the severity of the destruction.”[7] Despite this nonchalance, however, pressure from the news media—the unconscious of the nation in those days—slowly helped to formulate laws and regulations.

Before these laws were passed in the second half of the nineteenth century, property owners were not held responsible for injuries or loss of lives resulting from fires in their buildings. It was only after a series of extreme cases of what we would now call criminal negligence that owners were obliged to install alternative means of egress in case of a calamity. In the winter of 1860, the New York Times started a campaign for better safety measures after a particularly horrible fire in a large tenement house on Elm Street claimed thirty lives. Historian Sara E. Wermiel writes: “This fire outraged the editors of the New York Times, who reproached New Yorkers for fretting over the welfare of slaves in the South while ignoring the safety of their own poor neighbors. Within a couple of months, the state enacted a new, comprehensive building code for New York City. An early draft of this law called for making landlords liable for injuries sustained at fires in their buildings, but lawmakers deleted this provision from the final version. Nonetheless, this 1860 law introduced several novel requirements pertaining to egress, the most important of which was a device that became a signature feature of America’s downtowns: the outside fire escape.”[8]

The 1860 law required every large apartment building (nine or more units) in the city to have either a fireproof stair tower or else “fireproof balconies on each story on the outside of the building, connected by fireproof stairs.” The vagueness of the wording led to the development of many types of fire escapes, the majority of which paid lip service to the new laws. Other American cities and states soon followed New York’s lead, but it was not until 1885 that a fire escape was legally defined as an “outside, open, iron stairway, of not more than forty-five degrees slant, with steps not less than six inches in width and twenty-four inches in length.”[9] Good intentions notwithstanding, the external fire escape never completely fulfilled expectations. Whoever tried to climb out of a window on the fifth floor of a burning tenement, let alone a twenty-story office building, was challenging fate. Fire escapes were either too cold or too hot to allow a comfortable hold, and this does not even take into account the period’s uncomfortable clothes and slippery, leather-soled shoes.

Another infamous New York fire, the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, announced the effective end of the life of the outside fire escape. Though it finally claimed 146 lives, the fire itself had not been especially dangerous. The Asch Building, of which only the top floors were used by the Triangle Shirtwaist company, was a solid fireproof building which, almost a century after the fire, is still standing in what is now the New York University campus. But the dramatic loss of life was the result of the hopelessly inadequate system of emergency egresses established by the owners of the sweatshop, who found it cheaper to purchase fire insurance policies than invest in fire-prevention systems. The Asch Building’s fire escape, which could not be easily reached because of a locked door, became so hot that it bent and finally collapsed under the weight of those who had found their way there, sending twenty-five garment workers down to their deaths in the alley below. After the 1911 disaster, the construction of external fire escapes on new buildings was increasingly restricted by individual states and localities in favor of internal fire-resistant stairs.[10]

A device more futile or treacherous than the average present-day fire escape would be hard to devise. True, many lives have been saved by means of them, because any additional means of escape or of rescue is of value; but a great number of lives, I believe, have been lost as well. Usually of material too light to stand the strain they are called upon to bear in times of crowding and emergency, they are also, in many cases, improperly anchored to the walls, tearing away and sagging under the weight of thronging bodies. ... They readily become hot and many an unfortunate has been severely burned on them, or driven back into the furnace, as was the case at the famous fire in the Windsor Hotel, in the Washington Place [Triangle Shirtwaist] fire already mentioned and in scores of minor disasters in tenement houses, lofts and hotels throughout the country.[12]

Another drawback of the outside fire escape was that it was practically an open invitation to burglars. From street level or from neighboring platforms, with or without athletic training, access was guaranteed. To solve this problem, windows were barricaded with a variety of grilles, the most popular of which was the retractable grille. But the solution was even more dangerous than the problem. In case of an emergency, the barrier could get stuck, be locked, and, in case of a fire, it could be deformed by the heat and jammed shut.

It was to be expected that in the end, external fire escapes were no more than what they had been from the beginning: quick solutions for an otherwise insoluble situation. Landlords preferred the fire escape as a quick fix for their hazardous real estate. And as far as quick fixes went, fire escapes were more concerned with the law than safety. The true solution was to raise building construction standards. People like Croker and Dougherty continued to warn against the dangers of flammable materials and proposed the use of fireproofing techniques, not only for the outside but, even more urgently, for the inside of buildings. Their key proposal was internal, insulated, fireproof stairs—an option that many European countries had already adopted.

Although Croker was responsible for important revisions of the fire laws in effect in 1911 (which, together with other recommendations, formed the basis of New York City’s Building Exits Code of 1923), few of his proposed solutions, such as interior fireproof stairs, were, or indeed still have been, fully implemented. In fact, building codes since 1860 had called for such improvements in “buildings of a public character” but owners had nevertheless been allowed to resort to the outside fire escape, which remained “the all-purpose solution for emergency egress.”[13]

But fire escapes were seen not only as mementos of past urban devastation, but also as presaging catastrophes in the making. They were thought to act as admonitions of “the accident,” in Paul Virilio’s words, of “what can happen,” a bit like the dinky life jackets with their pull cords and ominous toy whistles hiding under the seats of our passenger airliners. Visitors like Jules Huret were very much aware of the fire escape’s numinous character. As a caption for a photograph in his monumental L’amérique moderne (1911), he wrote: “The East Side, populous neighborhood in New York. Fires occur in this neighborhood with such frequency that, as a security measure, the floors of the apartment buildings are connected by iron ladders.”[14]

Paris, almost entirely built of stone and brick and the first modern city with wide, stone-paved streets and squares, suffered numerous local fires due to its numerous theaters, which were often made of wood but employed fire for lighting and stage effects. The Palais Royal, the city’s central pleasure garden, was home to two important theaters, the Comédie Française and the Théâtre du Palais Royal. The Comédie Française was destroyed by fire in 1900 and rebuilt with interior fire stairs. The Théâtre du Palais Royal, on the other hand, lacking surplus interior space and with no room to expand, had in 1880 commissioned the respected architect Paul Sédille, famous for the Parisian department store Au Printemps, to provide the theater with an appropriate egress system.[15] The balconies and staircases of this rare European example of an external fire escape are compacted into one block and integrated gracefully onto the back of the theater. The result was widely admired for its elegance.

Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, European cities increased their immunity against fire, whereas on the other side of the Atlantic, wood remained the preferred building material, one reason why there are still to this day annual conflagrations in the coastal areas of greater Los Angeles.

From Alfred Stieglitz to Alfred Hitchcock, fire escapes were photographed, painted, sketched, and filmed. Fire escapes invite photography, just as masts of sailing boats invited painters.[17] They add elegance to otherwise uninteresting blocks of brick. Zigzag lines in dark paint over a background of glowing brick were used by George Bellows in his 1913 Cliff Dwellers. John Sloan’s rooftop scene Pigeons (1910) used fire escapes and balconies to enliven the faceless façades of New York townhouses. Still, picturesque or not, many house owners wanted to get rid of their fire escapes at the first opportunity. This became possible in the 1960s and early 1970s with the great clean-up that raged across all the cities of the Western world. Everything had to make way for the new motor-based economy.

A small army of preservationists furiously resisted the mayor and his developers. Professional and amateur photographers alike took roll after roll of pictures of threatened buildings. A denser concentration of monuments of pre-modern architecture was hard to find. Shoulder to shoulder they stood, challenging the wrecker’s ball: William Jenney’s Manhattan Building, Burnham and Root’s Fisher Building, their Monadnock Building, and Holabird and Roche’s Marquette Building. Thanks to the combined preservationist forces, the South Dearborn landmarks were saved. By 1978, most of the surviving Chicago School buildings had been designated historical landmarks.

The 1896 Fisher Building, one of the most elegant but covered in soot and provisionally patched up, was subsequently restored as a luxury apartment-hotel. Soot, boards, and signs with forgotten commercial messages were removed. The pretty putto over the main entrance of the building, obscured in photographs from 1972, has now been freed from all the obscuring junk and restored to its original glory. But where is its F. P. Smith fire escape, visible in so many earlier photographs? Chicago was not only a great place to study early skyscrapers, it was also a place to study old fire escapes. At some point, early, tall Chicago Style buildings had been equipped with external fire escapes, and these enormous fire escapes had to be manufactured by large iron works. Naturally, they were more legal additives than instruments of salvation (who in his right, or wrong, mind would jump on a fire escape twenty or more floors above street level?). But from the standpoint of architectural history, they did at least bear the names of their makers. Stamped in a medal-shaped counterweight on the lower landing of the fire escape on the Fisher Building was the name “F. P. Smith Wire and Iron Works, Chicago.” With some difficulty, it could still be read in a faded color slide that I took in 1971. The same F. P. Smith was also the author of the fire escape at an even more famous front, that of the Sullivan and Adler Auditorium Building at the corner of South Michigan Avenue and Congress Parkway, just a block away from the Fisher Building. Another signed fire escape, which was cleared away, was on an equally famous former office building, now turned residential, on South Dearborn Street: William LeBaron Jenney’s bay-windowed Manhattan Building of 1891. Pictures from the period of analogue photography allow endless enlargement, and so we can see the decorative counterweight and lever bearing the name of its maker: “United States Fire Escape Co. Chicago, Ill.”[19]

Yet, by and large, fire escapes are anonymous. Their makers might have been foundries, modest iron works, or small-scale blacksmiths who specialized in individually adapting ready-made fire escapes. Some manufacturers advertised in architectural magazines, as did Marshall Brothers of Pittsburgh with their “Iron City Elevator Works,” offering ready-made units of balconies and stairs for existing buildings. But for the rest we are left with guesswork. Everything made of iron is usually stamped with the name and address of its maker: man-hole covers, steel-rimmed curbs, and cast-iron basement skylights are extensively signed.[20] Former industrial districts such as Manhattan’s SoHo functioned as open-air catalogues for the iron works that made their façades. So why were fire escapes left anonymous?

Maybe it had to do with scale. The tall Chicago buildings relied on large companies to comply with the safety codes, but the more modest units could be serviced by small workshops. Since fire escapes were not forged but assembled from available strips of iron and bolted and welded together, even a small smithy could provide an average building with an average fire escape.

All his life, Vanelli had manufactured decorative ironwork, railings, stairs, fences, and, of course, fire escapes. He also repaired them. I had first spotted the Particular Ironworks at 52 Greene Street (now a design shop of props and sets) when I was on a photo tour in 1975 but it was in 2005 on a field trip with art history students that I finally met Joe and was invited into the workshop. In the thirty years that had passed, not much had changed, it seemed. The fire escape over the door had deteriorated further and the front had been given a new coat of grey paint. Inside, cast iron decorative parts were everywhere, sharing tables and floors with loose ends of steel, rolls of wire, tools, and machines. Various devices for bending and punching metal occupied the basement floor. The jewel in the crown was a German metal-forming machine. Smiths like Vanelli occasionally worked from drawings if larger commissions were at hand. Blueprints were uncomplicated affairs, concentrating primarily on points of attachment, which, for example, distinguished type “A” from type “B,” the former refering to standing triangular supports, and the latter to hanging supports. Reference sources with models, guidelines, and regulations remained restricted to one volume: Daniel M. Driscoll’s Architectural Iron Design of 1926, as then required by the laws of New York.[22] For the rest, ironworkers followed model and tradition. One freedom they allowed themselves, however, was the decorative pattern of the fences. Particular Iron Works, for example, filled the vertical parts of the balconies with squares divided by diagonal strips. Others used circular motifs, straight vertical bars, vertical and horizontal bars, curved bars, bent balusters, and so forth. These different patterns were, in fact, their signatures.

- David W. Chen, “An Escape, and a Retreat: A Neighborhood Communicates, Plays and Daydreams on Its Porches in the Sky,” The New York Times, 15 August 2004, pp. 33 and 38–39. Early egress laws concentrated on buildings with high occupancy, such as tenements, hotels, factories, and office buildings. Housing for the more affluent was generally better built, was less densely occupied, and had safer egresses.

- Ibid.

- In Amsterdam, where fire escapes are non-existent and balconies are rare, a new element has appeared recently: balconies that look like fire escapes. Stuck on brick-faced walls, the new balconies are like baskets of black iron.

- The film West Side Story was partly shot on location in Manhattan in abandoned West Side tenements around 110th Street.

- Roger C. Mardon, www.romar.org.uk, accessed 16 April 2002.

- The purpose of the hatches in this early period was to enable firefighters to reach roof and chimney fires. Sara E. Wermiel writes: “One of the earliest built-in kinds of alternative exit was the roof hatch. In the late 1700s, a mutual fire insurance company, the Philadelphia Contributionship, required its policyholders to put trap doors in their roofs. Charlestown, Massachusetts, across the harbor from Boston, took up this idea in 1810, when it called for every building to have a roof hatch (called a “scuttle”) as well as a ladder leading to it and a “safe railing on the roof.” See Sara E. Wermiel, The Fireproof Building: Technology and Public Safety in the Nineteenth-Century American City (Baltimore & London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000), p. 189.

- Fire historians Margaret Hindle Hazen & Robert Hazen tell us that in the US, even in the twentieth century, a disproportionately large percentage of dwellings were made of wood. “Sometimes the combustibility of the basic building blocks of American life remained hidden or ignored until a disastrous fire reminded the public of its perpetual vulnerability.” See Margaret Hindle Hazen & Robert Hazen, Keepers of the Flame: The Role of Fire in American Culture, 1775–1925 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992), p. 78.

- Sara E. Wermiel, The Fireproof Building, op. cit., p. 190.

- Sara E. Wermiel, “No Exit: The Rise and Demise of the Outside Fire Escape,” Technology and Culture, vol. 44, no. 2 (April 2003), p. 271.

- Ibid., p. 281.

- Thomas F. Dougherty & Paul W. Kearney, Fire (New York & London: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1931), pp. 178–179.

- Edward F. Croker, Fire Prevention (New York: Dodd Mead & Company, 1912), pp. 98–99.

- Sara E. Wermiel, The Fireproof Building, op. cit., p. 191.

- Jules Huret, L’amérique moderne (Paris: Pierre Lafitte & Cie, 1911) vol. 1, caption for plate 5. Translation by author.

- See Bernard Marrey & Paul Chemetov, Familièrement inconnues: Architectures, Paris 1848–1914 (Paris: Dunod, 1976), p. 54.

- William Gilpin, quoted in Christopher Hussey, The Picturesque: Studies in a Point of View (London: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1927), p. 117.

- Thomas A. P. Van Leeuwen, “Portrait of Two Generations: The Photography of John Vanderpant,” in Pronk & De Ruiter, eds., Foto Voorkeuren (Amsterdam: Voetnoot, 2007), pp. 87–90.

- Richard Cahan, They All Fall Down; Richard Nickel’s Struggle to Save America’s Architecture (Washington, DC: The Preservation Press, 1994), p. 11.

- Some other counterweights were stamped “Standard Fire-Escape Co. Chicago. Ill.,” “United States Fire-Escape Company, Chicago, Ill.,” and “Hanke Iron & Wire Works, Chicago, Ill.” The latter is still on the forty-story Pittsfield office building on East Washington, Chicago.

- Bogardus and Badger both left their names on columns, steel sidewalk covers, and glass-and-cast-iron basement skylights. Others were Jacob Mark from Worth Street; J. L. Jackson Iron Works of 28th/29th Street and Second Avenue; Cornell Iron Works of Center Street; G. R. Jackson & Burnet & Co., East River; Z. S. Ayres Iron Foundry of 45th Street, corner of 10th Avenue; Aetna Iron Works of Goerck Street; Nicholl & Ballerwell of Hanover Street; J. M. Duclos & Co., New York City; and Iron Works of 104th Street. Next to the name of the company, the precise address was often given as well. See Margot Gayle, Cast-iron Architecture of New York (New York: Dover Books, 1974).

- Nowadays suburbs are dominated by fenced-in private domains where everybody is afraid of everybody. Fire escapes may be obsolete, but demand for “artistic” monumental iron fences and customized gates is booming.

- Daniel M. Driscoll, Architectural Iron Design (As Required by the Laws of New York) (New York: Van Nostrand, 1926).

Thomas A. P. Van Leeuwen was professor of architectural history, cultural history, and art criticism at Leyden University for many years. He presently teaches at the Berlage Institute, Rotterdam. His books include The Skyward Trend of Thought: Metaphysics of the American Skyscraper (MIT Press, 1988) and The Springboard in the Pond: An Intimate History of the Swimming Pool (MIT Press, 1998). These studies are part of a tetralogy with each volume centered on the relationship between architecture and one of the classical elements. In preparation are Columns of Fire: The Un-doing of Architecture and The Thinking Foot: A Pedestrian View of Architecture.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.