Jacket Required

Judging a book by its dust cover

Alexandra Cardia

Defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as referring to “a protective (and usually decorative) paper cover placed around a bound book, usually with the title and author’s name printed on it,” the phrase “dust cover” or “dust jacket” was first used in the late nineteenth century. The earliest dust jackets, dating to the 1830s, encased the entire book. Their primary function was as protective wrapping, which means that many nineteenth-century dust jackets were disposed of or lost after being removed from their books. The standard library practice of unsheathing books before cataloging them for circulation has also contributed to the rarity of surviving early dust jackets.

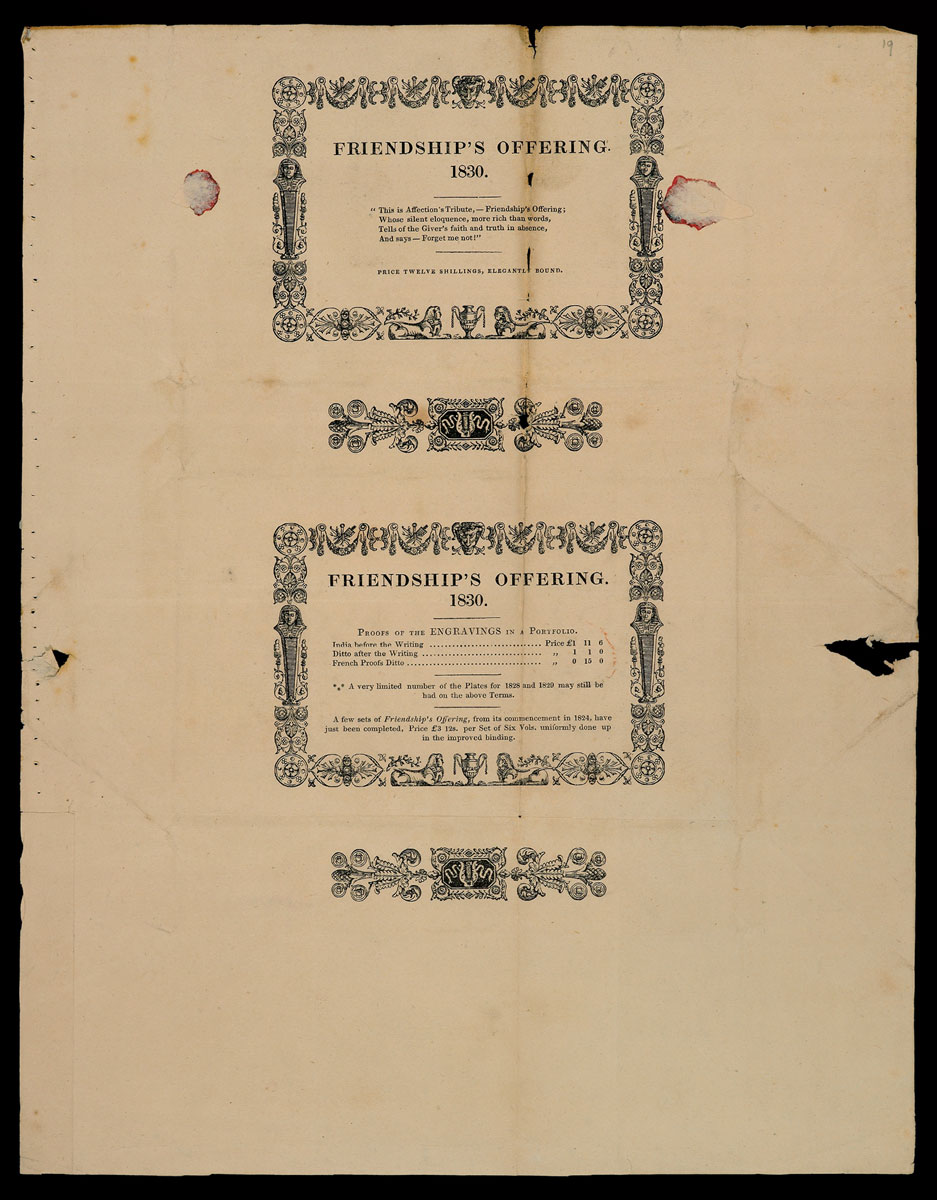

In April 2009, for example, one of the earliest-known dust jackets was found at Oxford University’s Bodleian Library. Hidden in an assortment of book-trade ephemera purchased in the 1890s and never fully catalogued, the worn and faded piece of paper imprinted with black ink had long been separated from the volume it encased, an 1830 gift book entitled Friendship’s Offering. Gift books, or literary annuals—popular collections of essays, short fiction, and poetry based upon late eighteenth-century French and German illuminated almanacs—were richly decorated volumes, bound in silk, leather, or glazed paper, and designed to be given away, particularly around the Christmas and New Year holidays. Dust jackets, such as the one at the Bodleian, ensured that the gift reached its recipient in perfect condition. Clive Hurst, the head of rare books and printed ephemera at the Bodleian, believes that such a dust jacket is more accurately described as a wrapper, “protecting the book from handling damage (which could include dust).” In fact, the creases where the paper had been folded around the volume, as well as remnants of wax where it had been sealed, are still visible on the jacket.

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, as publishers began to employ more durable bookbinding materials, the need for strictly protective wrappings diminished. The sober, utilitarian cover gave way to the dust jacket as advertising vehicle, culminating in the vivid graphics, stylized fonts, and “special effects” such as embossing and metallic inks that today scream from bookstore shelves everywhere.

Alexandra Cardia is a graduate student at New York University’s Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.