Something in the Air

Anthony McCall’s white cube problem

Colby Chamberlain

It was Marcel Duchamp who brought dust into the museum. In 1920, he took the pane of glass on which he had begun to create The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (also known as the Large Glass) and placed it on sawhorses by an open window in his New York studio, exposing it to the grit of the street below. According to his friend Henri-Pierre Roché, Duchamp hung a sign nearby to prevent cleaning attempts by well-meaning visitors: “Dust breeding,” it read. “To be respected.” When the artist Man Ray photographed the glass later that year, a thick film of dust had settled on the surface. Duchamp eventually wiped most of the dust clean, but left untouched a few select patches as an unorthodox means of coloring his composition. He had made work of doing nothing: dust, typically the trace of neglect, was instead the product of purposeful inactivity. The Large Glass now stands in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, a smudge on a pristine setting. That said, Duchamp’s dust is safely quarantined, sandwiched between panes of glass. (Man Ray later observed that the Large Glass was sufficiently sealed to be washable in the shower.) Though Duchamp called for dust to be respected, museums’ campaigns against it persist unabated—much to the chagrin of Anthony McCall.

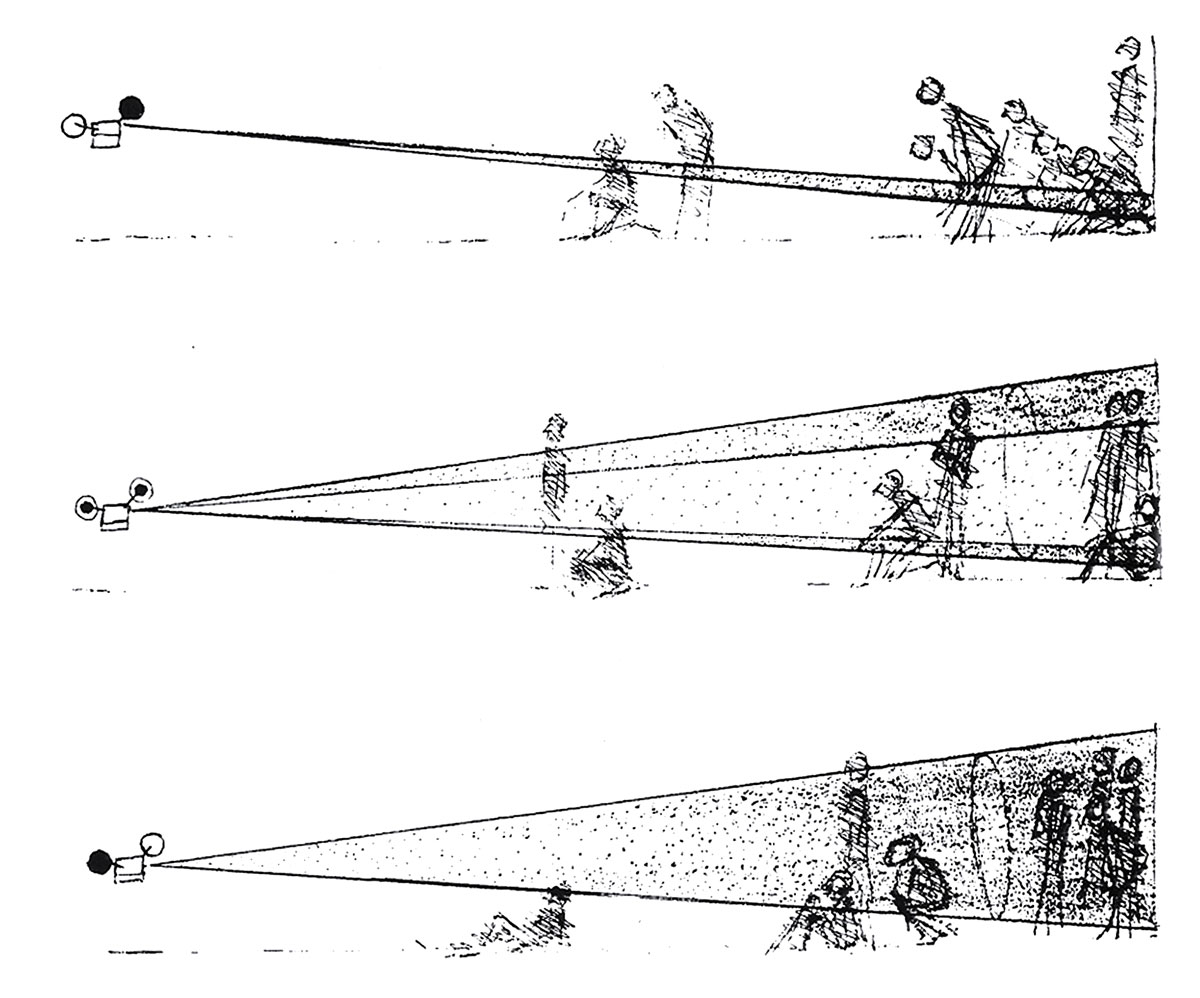

In 1973, McCall, an artist and graphic designer from England, was aboard a ship bound for New York when he came up with an idea for a new film, Line Describing a Cone. Looking at the film reel itself, the piece is extremely simple: a white dot appears on a black background and, over the course of thirty minutes’ worth of celluloid, that single dot grows into the outline of a circle. Now imagine that film projected across an empty room to a bare wall forty or so feet away. That single dot shoots out a narrow beam of light and, as the dot extends and curves, that initial beam becomes a veil. Three or four minutes pass, and the light begins to suggest the sloping surface of a cone, with the projector’s lens as its tip and the circle appearing on the opposite wall as its base. At the close of thirty minutes, the completed cone sits between projector and wall like a phantom megaphone, apparent enough that some viewers walk circumspectly around it, but so impalpable that others cross straight through. McCall dubbed it a “solid light” film.

Line Describing a Cone, as well as several subsequent variations, utilized the barest elements of film—celluloid and projected light—but it clearly needed to be experienced as a three-dimensional object, like a sculpture. The film’s straddling of two mediums accounts for its varied exhibition history: in New York alone, Line Describing a Cone was alternately screened at avant-garde cinemas, like Millennium Film Workshop, and downtown galleries, like Artists Space and the Clocktower. Neither setting was ideal, so each screening required advance preparation, such as removing chairs (in film theaters) or blacking out windows (in galleries). As it turned out, the formerly industrial trappings of these alternative venues provided McCall’s films with a crucial additional element: dust. If Duchamp’s dust settled over glass in a thick film, then floating dust functioned for McCall as a sort of diffuse screen that allowed his veils of light to be seen across space.

McCall emphasized the importance of air quality in a set of projection instructions he wrote in 1974: “The light of the beam is visible through contact with particles in the air, be they from dust, humidity or cigarette smoke. Smoking should not be prohibited.” But when McCall had the opportunity to exhibit outside of low-budget avant-garde enclaves, he found these stipulations more difficult to fulfill. Other venues were too tidy. During a 1975 screening of Line Describing a Cone at Malmö Konsthall in Sweden, he watched in horror as the usual veil of light simply failed to appear. He described his reaction in a 2007 interview with Mark Godfrey:

I raced out of the Konsthall, and across the road to a tobacconist, and hurried back into the projection space with three, lit, Swedish cigarettes in my mouth. I blew smoke into the air near the beams in an attempt to make them visible. This did help. However at that moment I was tapped on the shoulder. I turned round to find an angry-looking guard who confiscated the cigarettes and ordered me out of the room. So for the next fifteen minutes, an art audience drawn from the city of Malmö politely watched a three-dimensional projection that was absolutely invisible. If they were bored or disappointed, they didn’t show it.

The challenge of rendering his work visible in museum contexts was a significant factor in McCall’s decision to abandon his solid light films for over twenty years. More recently, a renewed interest in his work, along with the invention of sophisticated fog machines called hazers, has brought McCall back into the studio. But his earlier encounter with museums’ war on dust remains a cautionary tale of the often irreconcilable differences between the rough spaces where art is typically made and the pristine institutions that frequently present it. As much as nature abhors a vacuum, culture disdains cleanliness.

Colby Chamberlain is a Jacob K. Javits Fellow in the art history department at Columbia University. A former managing editor of Cabinet, he is a senior editor for the online magazine Triple Canopy.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.