Bachelor Pad Revolution

Josef Albers and the Command Records look

Eva Díaz

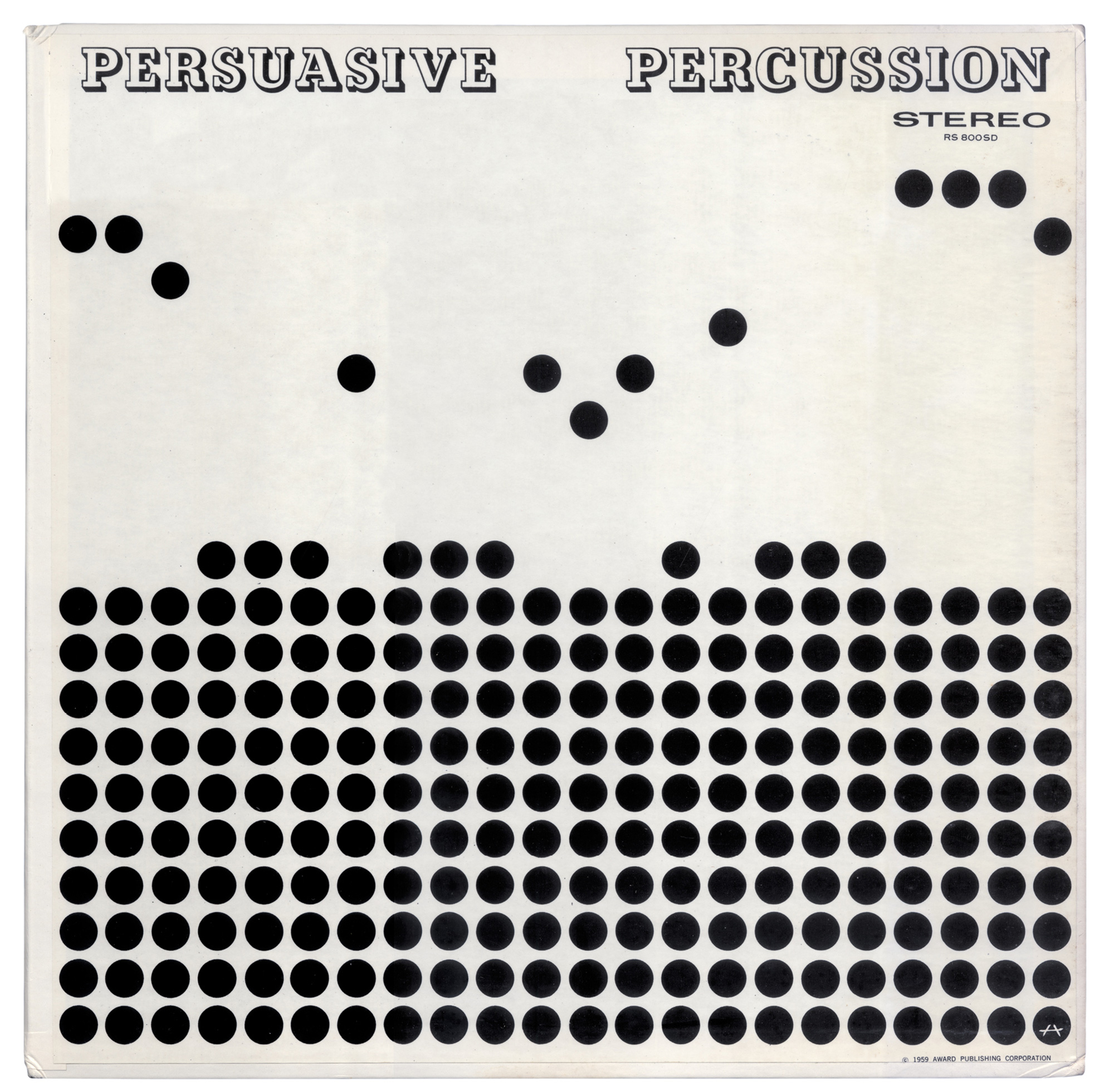

From 1959 to 1961, the artist Josef Albers designed seven LP album covers for Command Records. The first, Persuasive Percussion, with music by drummer-bandleader Terry Snyder, was a number one hit on the charts for thirteen weeks and stayed in the top forty for over two years. Its cover design is starkly graphic: a ten by twenty-two grid of black dots, each one centimeter in diameter, fills its bottom half. By the eleventh row, some of the dots have levitated out of their pre-determined berths, lending the composition a spacey-staccato quality.

I collect these Command albums; it’s probably as close as I’ll ever get to owning an Albers. Ironically, I’ve never listened to them; my record player has been out of commission for years. So until recently, I didn’t get a chance to experience how the graphic designs of one of the twentieth century’s most respected artists, and its preeminent color theorist, enhanced what I took to be the light elevator-music fare of albums promising “persuasive” percussion.

Finally, I heard some of the tracks on Youtube, on which there is a surprising amount of amateur footage employing the recordings. Many depict the record revolving on a turntable, some with the Albers album sleeve propped up behind the player. At first, these watching-paint-dry visuals puzzled me, but I came to understand that the high-fidelity sound of the pioneering stereo effects employed by Command Records founder Enoch Light attracts serious audiophiles who use the albums as test records for the main event: their expensive hi-fi setups, which they were showing off on the decidedly lo-fi website. Yet for all its technical virtuosity, the Light sound is itself muzak-y lite, an uninspired selection of recent pop hits covered as instrumental Latin jazzy confections. A reissue of Persuasive Percussion ran the phrase “BACHELOR PAD MUSIC” in a banner across its cover. In short, Enoch Light provided “sophisticated” lounge music for the Playboy man.

This was not what I associated with Albers, the Bauhaus master hired by Black Mountain College and later a professor at Yale University. Was this the case of the mandarin following the lure of mainstream success but instead veering headfirst toward the insipid? Not so: Albers’ output was, in fact, tremendously catholic, which may explain why Enoch Light’s daughter Julie, a student of Albers’s at Black Mountain College, recommended him to her father. Albers began his career at the Bauhaus as a glass artist, became the teaching master of the furniture workshop, and later led the wallpaper design workshop. At Black Mountain, he pursued a diverse sensibility, producing photographs, photomontages, furniture, lithographs, wood- and linoleum cuts, pen-and-ink drawings, and oil paintings, as well as a great deal of the college’s design output, including its dramatic concentric circle logo.

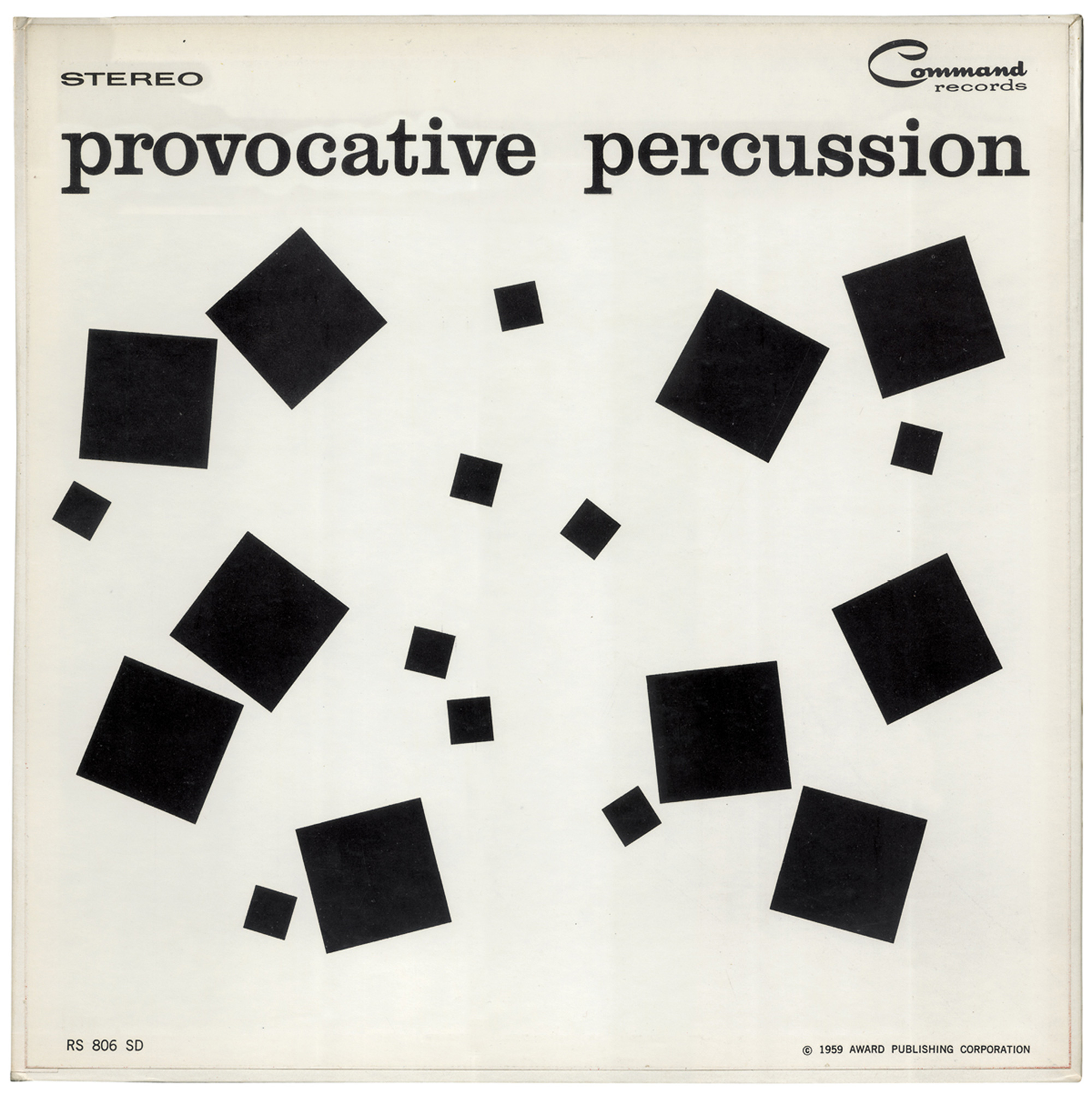

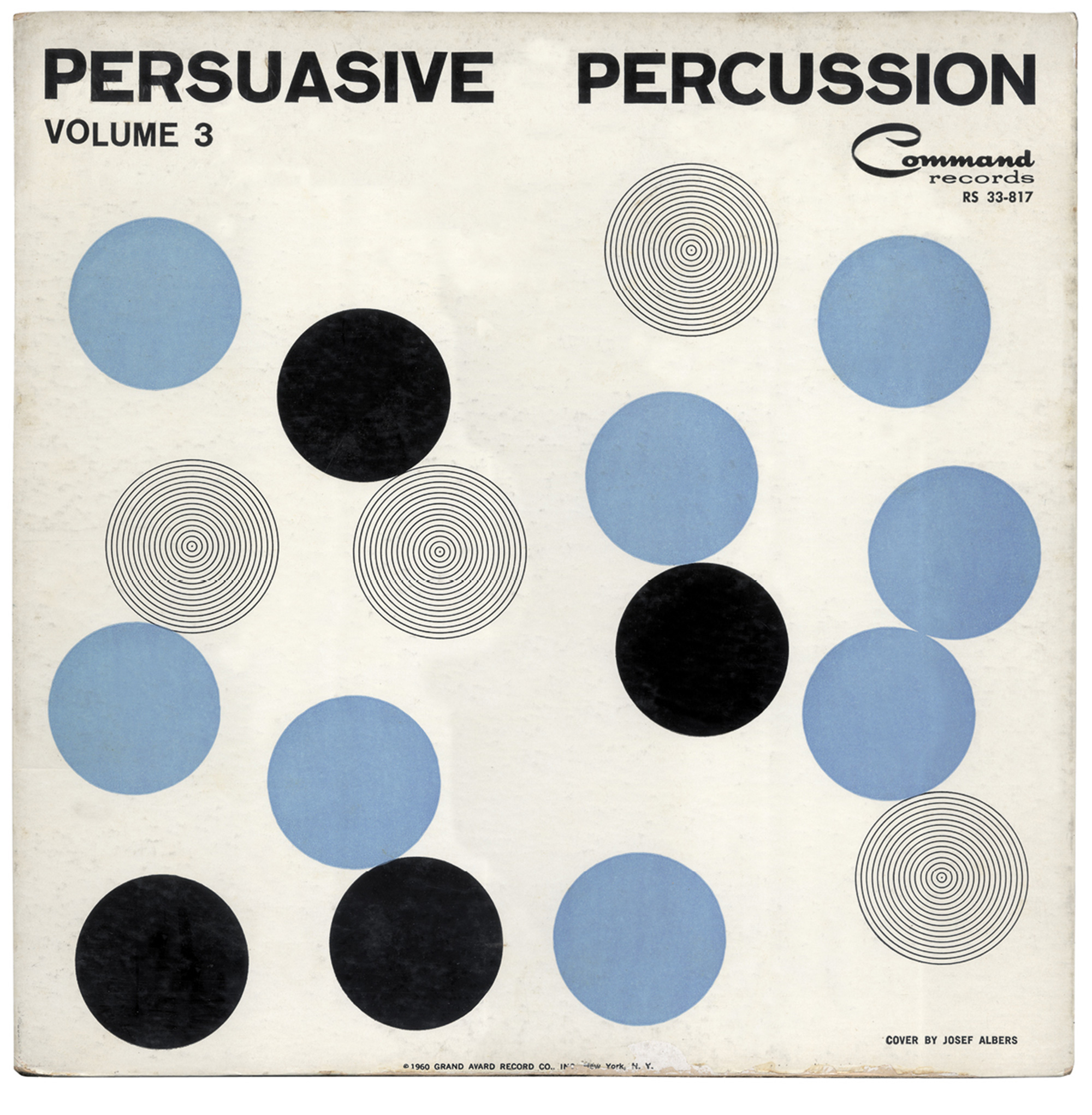

At the core of Albers’s practice and pedagogy was a model of experimentation—to him, that meant testing in material fashion the contingent possibilities of form using techniques of careful variation. Each of the album covers encourages dynamic relations between its elements rather than strictly symmetrical or mathematically expected ones, often by tweaking subtle details beyond a predictable seriality.

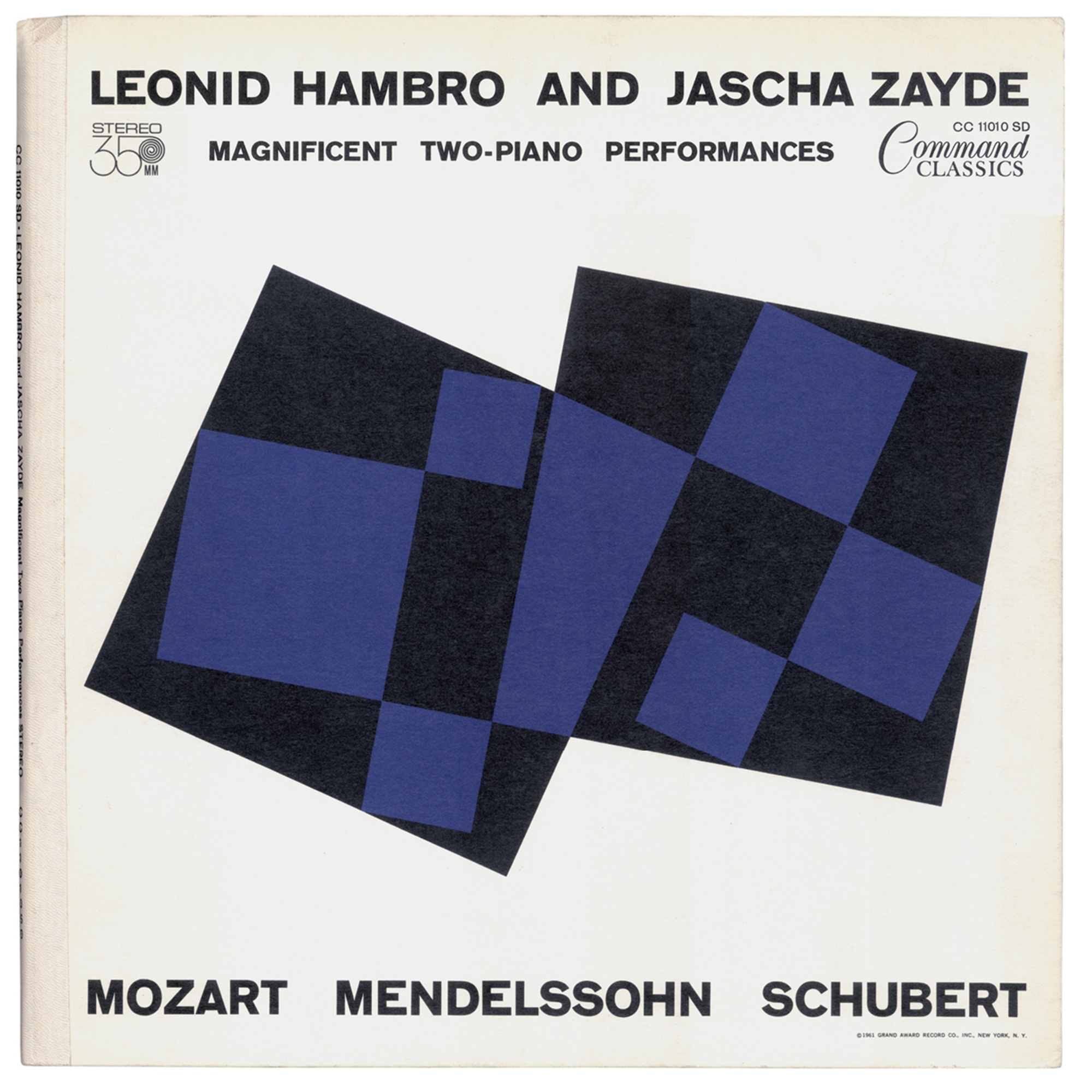

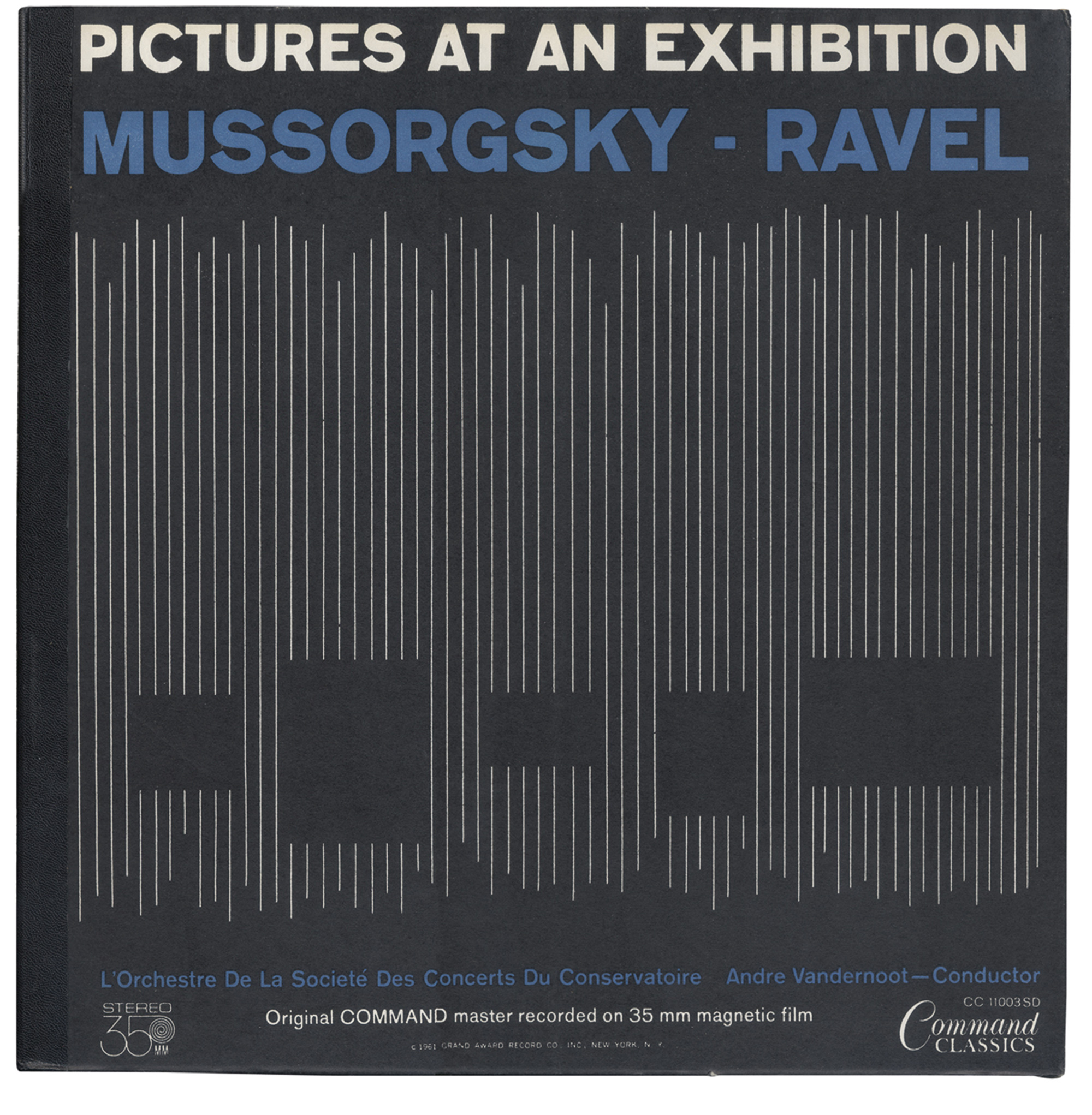

The record covers themselves are geometric abstract designs in a simple palette of black and white, sometimes accented with blue. Using a basic repertory of circles, squares, and lines on either white or black backgrounds, the albums make striking use of Albers’s “doing less with more” technique. In the follow-up Provocative Percussion, Albers features sixteen black squares of two different sizes that appear scattered on a white ground, as if by accident. Like the 1915 Jean Arp precedent of a grid of square color chips paradoxically “arranged” by chance, the sense of pushing the limits of composition towards the most dynamic arrangements, even those that tempt disorder, is palpable. Albers worked in the space of that limit: of the smallest compositional interventions and of minimal denotations that produce maximal effects. Working with subtle detail was part of the Bauhaus project Albers brought to the United States, emphasizing that everything in the world has form; training the eye in composition was a precondition for understanding and possibly transforming the material appearance of, and immaterial relations in, the world.

Retired from full-time teaching by the late 1950s, Albers accepted several commissions for major public art projects, including site-specific lobby murals at the Time and Life Building, the Corning Glass Building, and the Pan Am Building in New York City. As modest as album cover designs may appear next to these contemporaneous large-scale projects, creating original artwork for Command Records was an extension of Albers’s belief that each form and every object is part of a common and public visual culture of modernity.

For Albers, remaking the world by attending to all its seemingly inconsequential detail was an ethical proposition, a way of avoiding the casual, unthinking replication of bad design. Careless habits—habits that inhibit self-actualization and social progress—can be overcome, Albers believed, with the disciplined study of the constitution of the forms that compose the ubiquitous, though often overlooked, appearance of our surroundings. In this sense, Command Records initiated a bachelor pad revolt by hiring Albers—Light said that his desire for abstract designs was intended to break the habit of having “too many girls in too few clothes” on album covers. Attend to the details of design, Albers argued, and you can change the man.

Eva Díaz is assistant professor of contemporary art at Pratt Institute. In 2009, she received her Ph.D. from Princeton University for her dissertation “Chance and Design: Experimentation in Art at Black Mountain College.” She is currently working on a project about the influence of Buckminster Fuller on contemporary art called “Dome Culture in the 21st Century.”

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.