Good-Night Lyudi

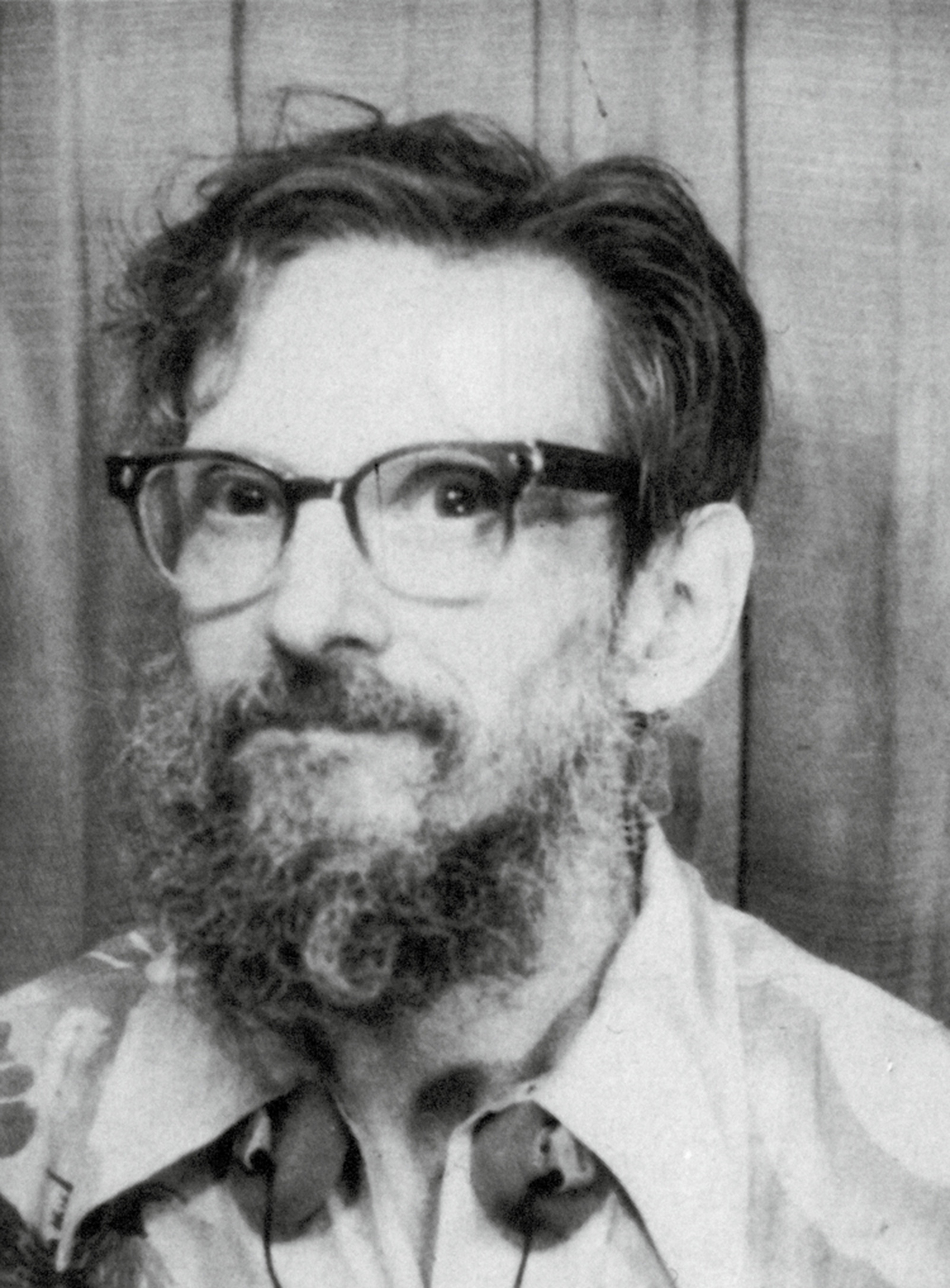

The fate of “schizophrenic language student” Louis Wolfson

Kevin McCann

In the mid-1950s, six months after escaping from an insane asylum “thanks to the negligence of two or three guards,” a young Louis Wolfson decided to devote himself wholeheartedly to the study of languages. He was in his mid-twenties and living again in Brooklyn with his one-eyed mother, who had called the police to have him committed. This period of his life, dominated by his fixation on language, became the subject of his first book, Le Schizo et les langues—which was written in French and printed in part in 1964 in Jean-Paul Sartre’s journal Les Temps modernes. Referring to himself in the third person throughout, Wolfson uses ironic phrases such as “the schizo,” “the mentally-ill young man,” and “the schizophrenic language student”[1] to describe his condition prior to his linguistic obsessions:

Despite his apparent incapacity, the psychotic had an exaggerated idea of his competence. Sometimes he even had the sense that he could do almost anything in almost any field if only he wanted to, and his major weakness was his lack of decision, these thoughts giving him an excuse to waste a lot of time doing nothing but think about what to do.[2]

It was, therefore, with the expectation of accomplishing great things that Wolfson began his immersion in foreign languages, starting with French, German, Russian, and Hebrew. Having acquired the ability to read and write in his own language belatedly and only with difficulty, and furthermore socially outcast, sexually impotent,[3] and apparently unfit for work of any kind, Wolfson’s desire to prove himself by becoming a polyglot quickly became fanatical. Though he continued to live in his mother’s apartment, Wolfson decided to eschew any contact with the English language. To drown out people speaking English, he used a short-wave radio tuned to foreign language or classical music broadcasts,[4] or alternatively stuck his fingers in his ears, wriggling them about and making gurgling noises in his throat when, for instance, his mother burst into his room to tell him something.

It was, of course, inevitable that spoken and written English would repeatedly penetrate Wolfson’s defenses. In order to deal with this, he attempted to transmute whatever English words he encountered into foreign words similar in both sound and meaning. The word milk, for example, was relatively innocuous since Wolfson could effortlessly convert it into any number of exact equivalents, such as the German Milch, the Russian moloko, the Danish maelk, or even the Polish mleko. More difficult words, such as ladies, could cause Wolfson hours of anguish. (The word was conjured every time he heard his mother play the tune Good-Night Ladies on the electric organ.) In public places, he was hesitant to go the bathroom because he feared seeing the word Ladies written on an adjacent bathroom door. He considered using the German Leute, a gender-neutral word meaning “people,” as the l-t combination was close enough to the l-d in the original, and ladies are a subset of people. He wasn’t, however, fully satisfied until he came across the Russian lyudi. This also meant “people,” but he preferred it because he had only recently learned the word, and from then on he could use ladies as a mnemonic device that would help him to recall the Russian word and all of its declensions.

In addition to accepting a certain level of semantic deviation, Wolfson’s defensive system permitted the mixing of languages, the use of repetition, and the addition of superfluous sounds or syllables. He even allowed himself occasional foreign neologisms. For instance, when trying to do away with the word early, Wolfson considered a French expression for “right away,” sur-le-champ, since it contained the proper r and l sounds. He also considered the semantically closer de bonne heure, which would have to be followed by matinalement to incorporate the l sound—effectively saying early twice and using seven syllables to replace two. He finally settled upon a combination of the German prefix Ur, denoting something prehistoric or originary, and the suffix -lich, a cognate of the English -ly, creating Urlich, a non-existent word that literally denotes “in an antediluvian manner.”

Though difficult words caused anguish, they also provided a greater sense of accomplishment when finally neutralized. Wolfson was proudest when he felt he had discovered a general rule. For instance, he discovered that the letter combination dg in English words can generally be replaced by ck in German: thus the German word for “bridge” is Brücke, the English word edge has a similar meaning to Ecke, and the German word Rücken (back) is, geographically, not so far in meaning from the English word ridge, which is also used to describe the back of an animal. For Wolfson, such discoveries constituted scientific breakthroughs, and gave him the sense of contributing to the sum total of human knowledge.

• • •

Whether or not this was true, Wolfson made a considerable contribution to the discourse of a generation of (primarily French) intellectuals. In the 1960s and 1970s, just about every major figure in French intellectual life—including Jean Paulhan, Jacques Lacan, and Roman Jakobson—read Wolfson. Raymond Queneau thought he was extraordinarily funny. Gilles Deleuze wrote about him in The Logic of Sense, and went on to write a preface to Le Schizo et les langues, which he extended and revised in Essays Critical and Clinical. In 2009, Jean-Bertrand Pontalis published Le Dossier Wolfson, a collection of texts on Wolfson by such prominent figures as Michel Foucault, Paul Auster, and Jean-Marie Le Clézio. Although Le Schizo et les langues is still read and discussed in France, Wolfson’s second book, Ma mère, musicienne, est morte, did not find a wide audience. Neither of Wolfson’s books has ever been translated into English (and Le Schizo, being in part a tract against the English language, perhaps never should be), and Wolfson is only read outside of France by a small number of Francophone academics interested in French theory, problems of translation, or psychoanalysis.

It is unfortunate that Wolfson so often appears in critical literature as merely an interesting psychological case study or a pleasantly eccentric and extreme illustration of certain observations on language and translation—even Deleuze bluntly stated that what Wolfson created was neither a literary nor a scientific work. Wolfson is a talented writer, and although he was unquestionably paranoid, he was not generally delusional. Parallels have been drawn, notably by Foucault and Deleuze, between Wolfson’s linguistic transformations and those of writers Raymond Roussel and Jean-Pierre Brisset. Another interesting parallel can be drawn to German judge Daniel Paul Schreber (perhaps the most famous paranoid-schizophrenic memoirist and one of Freud’s most celebrated case studies). Schreber believed that God was sending down rays in the form of birds to pour “corpse poison” into his body, and this they would do by repeating certain words and phrases learned by rote. Schreber would often cut the birds off by saying something very similar to what they were supposed to be saying, for instance, Atemnot in place of Abendrot, and this would confuse the birds, preventing them from delivering their poison. Schreber also continually had to block the voices of spirits, which would pester him if he ever stopped thinking or making noise. Playing the piano helped him to drown them out, and occasionally if Schreber had no educated companions for conversation and no equivalent distraction, he would slip into prolonged, uncontrollable fits of bellowing. Spirit voices spoke to him in “God’s language,” which was an antiquated but recognizable and beautiful form of German. By stimulating nerve endings in his head, the spirits (themselves nerves) could make Schreber think certain words against his will (as piano tunes did for Wolfson). Whereas Schreber, who was always painfully earnest, is sometimes unintentionally comical (insisting that God employs miracles to make him go to the bathroom and simultaneously ensure that the bathroom is occupied), Wolfson is quite aware that his predicament is ludicrous, playing up the absurdity of his own life and character, as is clear from the earliest pages of Le Schizo:

Having just one eye, this condition also became [Wolfson’s mother’s] favorite excuse for her lack of education and her justification to avoid reading (reading tired her eye, she said), but this visual deficit didn’t prevent her from spending hours playing on her electric organ [using several volumes of sheet music with the notes printed rather small]. Naturally, her optical weakness in no way seemed to interfere with the capacity of her speech organs (perhaps it was just the opposite), and she spoke, at least for the most part, with a very high and sharp voice, although she could whisper very well on the telephone when she wanted to clandestinely arrange her son’s admission into a mental hospital.

Adopting an indirect free style, Wolfson participates in both the sense of monumental importance his past self gave to certain petty annoyances or linguistic “discoveries,” and the distance and skepticism his reader is bound to feel regarding those events. The result is a style that seems to parody Wolfson himself, as well as those who would dismiss him as insane or perverted. Of course, this vacillation reflects Wolfson’s tendency to waver between under- and over-estimating himself, a dynamic that is exacerbated by his language studies. While Wolfson prides himself on the extraordinary feat of having taught himself several languages, every real-life situation he encounters in which he might apply those languages ends in abject failure. For example, when the New York Public Library hosted an exhibition of Soviet books, Wolfson attempted to ask the hostess in Russian whether she had any scholarly works that included marks to show where emphasis should be laid in pronouncing words. The hostess responded in English that they had kids’ books with little stories in them. (Wolfson’s ensuing mental anguish was eventually partially ameliorated by supplanting the word kids with the German word Kinder.) On several occasions, Wolfson had the opportunity to interact with a francophone handyman who was working behind his house and was even called upon to help his mother communicate with the worker, as he spoke no English and she knew no French. While his dealings with the Frenchman were on the whole a good deal more successful than with the Russian woman, Wolfson recalls that when he is first called on to help, “he didn’t hear, or rather … didn’t understand very well because his knowledge of that language simply wasn’t as good as he sometimes liked to imagine.” And when a rabbi came to counsel his mother on her deathbed, Wolfson attempted to say “God is the bomb” to him in Hebrew. (At this point Wolfson had taken to hoping for the world to be destroyed in a nuclear holocaust, ending sickness and death forever. Salvation, and therefore the highest divinity Wolfson would acknowledge, was the sum total of the world’s nuclear arsenal.) But he had mistakenly used the indefinite article, and the rabbi responded with a request for clarification in English: “God is a bomb?” The rabbi disagreed in English, then turned his attention to the mother. The only other Hebrew Wolfson managed to employ in this episode was Mazel tov, slipped in at an inappropriate moment.[5]

The fanaticism Wolfson brings to his linguistic study largely stems from a compulsive/addictive personality, but it also appears to be part of an over-compensatory technique. Wolfson believes himself to be weak-willed, and cannot trust himself to regularly follow through with any activity he does not raise to the level of a compulsion. He describes feeling not just pained, but guilty when he hears English. He is ashamed that the time he spends locked away to learn languages is mostly wasted and that his progress is so slow. Wolfson vainly struggles to keep himself in check, to set rules and limits so as not to give in to his self-destructive tendencies. His orgies of eating provide a striking illustration of these mechanisms of addiction. Wolfson describes himself on the first page of Le Schizo as thin and undernourished. He is nevertheless concerned not to let himself go, and in fact is strongly drawn to junk food. Each week after his mother goes shopping, she puts the groceries away and then leaves the apartment, knowing that her son won’t eat as long as she’s there. Though Wolfson knows that he overeats every week, sometimes to the point of making himself violently ill, he nevertheless hurries to the kitchen as soon as his mother is gone. He admonishes himself to eat very little, repeating clusters of foreign words to himself as he does:

It was, meanwhile, dangerous for him to open one of those containers of food to see what was inside, because he would be tempted to try a piece, feeling in a sense obliged to justify having opened the pack; and having done that, he would doubtless decide that a second or third piece would justify it even better (and, of course, the container is already open and in front of him) and, after that a fourth or even a fifth piece wouldn’t be too much either; so he could very well think that the sixth or seventh piece would be the last, or if not, that the eighth or certainly the ninth piece would be, and then each additional piece might seem to him insignificant. Becoming more and more overwhelmed, he might possibly lose all control over his appetite; he would read, would study, would repeat groups of foreign words less and less efficiently, even ceasing or rather forgetting to study, having equally forgotten all his thoughts from during the day on the subject of eating, his vows to only eat a little and to only do so while studying at each instant, having equally forgotten his regrets and self-reproaches after so many other meals.[6]

The description of Wolfson’s food orgies lasts for several pages and ends when he has madly torn open all the interesting containers of food and eaten every last scrap, when he is too weak to brush his teeth or even rinse,[7] with him alternately thinking that his weakness proves that he is too stupid to ever truly learn several languages, or (when less deflated) upbraiding himself with the thought that it is shameful that a man who was able to teach himself five languages could so completely forget everything he had promised himself about eating. Such anxieties notwithstanding, Wolfson knows he has to eat something, in part because if his mother comes home and sees he hasn’t eaten, she’ll come in and complain in English about it. And he tells himself these things in bad conscience, knowing that her English will ultimately bother him a lot less than the self-loathing born of the knowledge that he’s once again been a glutton.

• • •

On her deathbed in 1977, Wolfson’s mother asked him to make her two promises, neither of which he was able to keep. The first was that he stop betting on horses. Wolfson notes that he did, at least, drastically reduce his gambling, losing only a thousand dollars in the ten years following her death, as opposed to the five thousand he had lost in the two years immediately following the death of his father.[8] The second request—“Don’t talk about me Louis”[9]—was impossible for Wolfson to keep and this failure was, he wrote, his mother’s own fault for dying on the 138th day of the year when they lived on 138th street in Queens, and for doing so in an alliterative manner so compelling to him that the full title of his book about her reads: Ma mère, musicienne, est morte: De maladie maligne mardi à minuit au milieu du mois de mai mille 977 au mouroir Memorial à Manhattan.

That a coincidence in numbers and letters in an arbitrary system of signs should dictate Wolfson’s decision to write a second book signals a superstitious need to assign logic and order precisely where they seem least to belong. The space occupied in Wolfson’s first book by language is taken by horse races in the second. Games of chance, like phonetic signs, function only on the condition that they do not operate according to any calculable necessity. Nevertheless, Wolfson develops a system, alchemical in its complexity as well as in the magical thinking that underlies it, with which he attempts to predict which horses he should bet on. In this system he takes into account not only all the information he can find on the horse itself, its jockey, its owner, and the stables where it’s kept, but also calendar dates, holidays, and international events. On every Friday the thirteenth, Wolfson believes that thirteen-year-old horses are more likely to win. On 1 July 1976—Canada Day—it is difficult for him to decide whether to pick Québecois jockeys, because it is uncertain what their political position will be regarding Canadian unity. (And, furthermore, 1976 also being America’s bicentennial, it is likely that the Canadian jockeys will not want to shine too much out of respect for their adopted country.) On Mother’s Day, Wolfson notes that the horse that won against the greatest odds, Myakka Prince, was kept in a stable called Spinning Wheel, which was appropriate as Wolfson remembered a spinning wheel depicted in the painting known as “Whistler’s Mother.”[10] The following year, Wolfson bet on a horse from that stable on Mother’s Day and lost.

Wolfson was forty-seven when his mother died, and within days his stepfather had kicked him out of the house, leading to his relocation to francophone Montreal. (Wolfson’s father had left his mother, claiming not to have known about her glass eye when they married, and because of it he doubted that another man would want her. Shortly after she remarried, her second husband absconded with her diamond ring, and was picked up by the police at the airport. He then made numerous promises, and she dropped the charges. He stayed with her until her death, and at her deathbed dramatically shouted, “Why am I not dying too?”[11]) Though Wolfson hoped to win enough money at the track or playing the lottery to litter major periodicals with advertisements advocating the collective suicide of the human race, he couldn’t bear the thought of his mother’s death. Near the end of her illness, he devoted a remarkable amount of time and energy to poring over foreign medical journals hoping to stumble across a miracle cure. He pestered his mother’s doctor, constantly suggesting new treatments, at one time causing the doctor to ask in exasperation, “Where do you find all of this?” On his way home from the hospital just after her death, Wolfson wandered into a funeral home and stared at a body on display until the undertaker kicked him out. At home afterwards, he called the hospital and asked to have the doctor once again confirm the declaration of death. When he was unable to get the doctor on the phone, he broke down and screamed “Enema!” across the line.

Years later, looking over the notebooks his mother kept during her illness, Wolfson remarked, “She was not very prolific, unlike others who write and write, always wanting another best-seller, their umpteenth, and still more money and glory (and this perhaps hypocritically, in the sense that they rarely read what others write, lacking the time).” Clearly he was thinking of himself when he wrote “others,” but literary glory continued to elude Wolfson. Eventually ending up homeless in Montreal, working out of the libraries of the University of Montreal and the École des hautes études commerciales, the nearby francophone business school, Wolfson began to draft a manuscript for a third book, apparently once again centered around a search for structure in what might be taken as accidental events—this time using encounters and experiences in his everyday life that seemed strangely connected. However, the manuscript, which was kept in a student locker that Wolfson had taken to using, was thrown out by one of the campus janitors who mistook it for trash. Trying to recreate it from memory seemed an impossible project, as he later acknowledged: “That sense of strangeness and of marvel had already begun to dissipate.”

• • •

Yet if Wolfson’s writing never earned him a living, let alone make him a fortune, he did eventually strike it rich. In 1994, Wolfson managed to move out of Montreal, settling in San Juan, Puerto Rico, where he still lives today. In addition to being a non-English speaking locale, the island also had another feature that appealed to Wolfson’s obsessive personality: the world’s largest single-dish radio telescope. Located at Arecibo on the island’s northern coast, the observatory is used in part to collect data for research conducted by the University of California, Berkeley into evidence of extraterrestrial intelligence. As Wolfson himself told me in a recent phone interview, conducted in French: “For me, the question of the existence of alien life and the abundance of its dwellings was of immense philosophical importance, and I felt that it would be metaphysically-transcendentally crucial for me to be on that island when the discovery, which could come at any moment, was made.” The search for alien civilization goes on, but the move to Puerto Rico did in fact turn out to be crucial for Wolfson. On 9 April 2003, he spent $22.50 to buy fifteen “automatics”—tickets with numbers chosen by the computer—for Puerto Rico’s electronic lottery:

All in all, that night struck me as magic, supernatural, and divine for several reasons, of which this is doubtless the most important: as usual, I had bought the tickets, three with five games on each, at the last minute, even worrying that I might be too late—closing is at 9:30 pm and sometimes a few minutes earlier. Also as usual, I didn’t listen to the drawing as it took place, more or less at 10:05 pm, fearing that this might be bad luck. When I felt fairly certain that the die had already been cast—the winning balls drawn, determined—and I had as a result come a bit out of my “trance,” I believe I opened a box of my favorite brand of delicious raviolis, which I had just bought along with my lottery cards, and I ate them all. Around 11:00 pm, stripped down to just my shorts, I stretched out on my green cot—at that time I wasn’t using a regular bed—and I turned on the radio next to me to listen to the pre-recorded drawing on public radio station WIPR-AM. … The music having ended, the announcer explained in Spanish that we were going to hear the instrumental “Dreams Come True,” these three words spoken in English. For some reason or other, I immediately felt, with body and soul, that those three words spoken in English—my native tongue, which I desperately flee—were addressed supernaturally, divinely, and exclusively to me. I was so convinced that I had won the grand prize that I trembled for maybe five minutes and my eyes filled with tears of joy! During the course of my life, I had purchased maybe 20,000 or 25,000 lottery cards, but never, never had anything comparable happened to me. That night they didn’t play the pre-recorded drawing. They played a different piece of music after “Dreams Come True.” The next day, Thursday, April 10, 2003, I discovered by Internet that I had, in fact, won the grand prize. And I was the sole winner!

- Or, most famously, “le jeune ome sqizofrene.” Wolfson wanted his book to be published according to a revised orthography that he invented—removing the h as well as the second m in the word homme. He systematically removed u’s after q’s and tried to reduce ways of representing a single phoneme, so ph would systematically be replaced with f. Consciously or not, Wolfson introduced orthographic reforms similar to those suggested by the French grammarian Louis Meigret in the sixteenth century. Since the early seventeenth century—when French linguistic norms were rigidly set and usage, rather than etymology or logic, was instated as the determining principle for orthography—no further reforms of this nature had seriously been attempted.

- Louis Wolfson, Le Schizo et les langues (Paris: Gallimard, 1970), p. 32. (All translations mine.) Wolfson later wished to expand the book and change its title to “Point final à une planète infernale” (Full Stop to an Infernal Planet), but his additions were only ever published in French in the magazine Change in 1978, and translated into English along with earlier passages from the book in Semiotext(e) the same year. Wolfson clearly had a passion for alternate titles, as the original printing of the book had already presented two others on the title page: “La Phonétique chez le psychotique” and “Esquisses d’un étudiant de langues schizophrénique” (“The Psychotic’s Phonetics” and “Sketches of a Schizophrenic Language Student.”)

- In Le Schizo et les langues, Wolfson at length describes an encounter with a prostitute and makes reference to previous encounters, all of which ended with Wolfson’s inability to perform. Wolfson expresses heightened sexual excitement when he learns that the prostitute he has picked up plans to study social psychology, and Wolfson starts to fantasize about ending up permanently interned in an asylum where the prostitute would work as a nurse. In Wolfson’s second book, a womanizing uncle suggests he should hook him up with a girl, to which Wolfson responds that he had “tried to screw some whores, but without success. If you can’t, you can’t.” He then added that nurses made him think of an enema, and asked if they made his uncle Bert think of an enema as well. They didn’t.

- Wolfson wore this radio, or a tape player, around his neck. Later, he attached the radio to his belt with a “stethoscopic” headset plugged into it. In the 1980s, looking back, he was proud to note that he was doing this long before the invention of the Walkman.

- Louis Wolfson, Ma mère, musicienne, est morte... (Paris: Navarin Éditeur, 1984), p. 170.

- Le Schizo, op. cit., pp. 47–48.

- These hygienic shortcomings highlight more than anything the extent to which Wolfson had lost control of his desires, as normally his fear of microscopic worms is so great that he carefully avoids letting his food—which could potentially have microscopic eggs and larvae on them—even touch his lips. He would certainly never touch anything he was going to eat with his hands (he ate his junk food directly from the package), or consume any food that hadn’t been properly cooked or hermetically sealed a moment before. At the height of his food orgies, however, he stopped taking any precaution whatsoever and handled all his food freely, shoveling it into his mouth as quickly as he could.

- The exact date of the death of Wolfson’s father is unclear, but he passed away some time between the publication of Wolfson’s first and second books (i.e., between 1964 and 1976). The tone of emotional distance when he briefly mentions his father’s death in the second book suggests that it occurred some years before his mother’s illness.

- Ma mère, op. cit., p. 175.

- When I interviewed Wolfson, I pointed out to him that Whistler’s painting did not in fact contain a spinning wheel. He responded that he was perhaps thinking of a different picture from a book of reproductions his mother had once bought for fifty-one cents as an employee of the Book-of-the-Month Club.

- Ma mère, op. cit., p. 194.

Kevin McCann is a New York–based writer and academic. He is currently working on a novel titled The Path to Clear while pursuing a doctorate in French literature at New York University.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.