What Do Bubbles Taste Like?: An Interview with David Arnold

AHHHH, and then ERRRRR

Eben Klemm and David Arnold

Mountain climbers refer to the “champagne blues,” the phenomenon of cracking open a bottle of bubbly upon reaching the zenith only to be disappointed to find that it tastes flat. This is now known to be caused by the consumption of altitude sickness medicines that block the enzyme carbonic anhydrase 4, which is expressed on the surface of sour-sensing cells on the tongue. Although bubbles in drinks would seem as if they were perceived in a tactile manner, the detection and appreciation of carbonation in our bodies is an indicator of a complex neurological pathway, one where a gastronomical appreciation, paradoxically perhaps, goes against a basic biological warning system.

As director of culinary technology at the French Culinary Institute in New York, David Arnold researches how the preparation of food can be improved to better fit the natural construction of our culinary perception systems. He has collaborated with many noted chefs, including Wylie Dufresne of wd-50, Johnnie Iuzzini of Jean Georges, and Harold McGee, author of On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen. In one demonstration, he made three equally pressurized “soda” waters with different gas mixes—one of one hundred percent carbon dioxide (normal seltzer), one of one hundred percent nitrous oxide, and one a fifty-fifty mix of both. The different “tastes” of these waters provided the springboard for this discussion between Arnold and mixologist Eben Klemm, which took place in Arnold’s laboratory at the French Culinary Institute.

Eben Klemm: Let’s get a term straight: when aerating a liquid with a gas other than carbon dioxide, is there a word for that process? Gaseation?

David Arnold: Actually, we’ve never come up with a good term for what we’re doing with nitrous oxide.

Nitrogenation?

I don’t know. Maybe we can come up with a good term today. Bubbleation? Booboolaise? No matter what the gas, we have always used the term carbonation. If we went with nitro-something, people would think we were using nitrogen. People already use nitrogen for beer, to suppress carbon dioxide. Nitrogen isn’t soluble.

Until I tasted your “carbonated” waters, I had thought of aerated liquids as merely a textural experience—the perception of the absence, the nothingness, in a liquid; the physical feeling of bubbles popping. But when I drank your three different gas mixtures (CO2, NO2, and a 50-50 mix of both), I actually realized that there’s a taste sensation happening.

Right. And there’s another thing that I don’t normally address. In the case of straight-up aeration of something with body, like a foam, there’s a kind of bubble—“entrained air”—that’s different from dissolved gases like nitrous and makes the system even more complicated. But you’re right, when you’re talking about dissolved bubbles like nitrous and carbon dioxide, people don’t think of that as something that has its own taste. So when you taste nitrous by itself, laughing gas, it feels creamy, it actually has a sweet taste, and you taste a lot of bubbles but not a prickling sensation on the tongue. That means that the liveliness of the drink, the amount of bubbles coming out of the drink, is a separate sensation from the prickliness that you get on the tongue—that seltzer flavor, that ripping, tingling in your nose thing you get with CO2.

And that sensation of acid that comes from CO2 being broken down into a bicarbonate ion, so what you are actually “tasting” is pain.

When the CO2 breaks down, it frees up a proton ion that stimulates your sour cells. But if it was only acid, then when I take nitrous oxide and use it to carbonate lemonade it would have the same sensation as if you used CO2 to carbonate it, and that’s not the case.

Most of the things we drink carbonated are high-acid to begin with: soft drinks, champagne.

Right, and when you carbonate those drinks, they don’t taste more acidic. Technically, there is more acid, but not appreciably more. CO2-carbonated liquids taste not sweeter, but more syrupy. Everything seems a little more amped.

So you are saying is that it’s not just the perception from acid receptors, but something else as well.

Acid receptors are fairly brute receptors—they receive hydrogen ions, and they don’t care where they come from. If they were the only thing detecting CO2, you shouldn’t taste the difference between it and other bubbles.

When I tried the straight NO2-carbonated beverage it tasted like aspartame. Is that from nitric acid being formed?

No. Our taste buds perceive nitrous as being sweet. We don’t dissolve NO2. Carbonic anhydrase 4 is the enzyme that in our mouth converts CO2 to hydrogen and bicarbonate. We have this enzyme to detect foods that have gone sour. It’s a warning system. Of course, no normal fermentation produces nitrous, so if it tastes sweet that’s just random. Bottom line, it’s fairly useful to perceive CO2 in things. Now you have chefs trying to carbonate solid things, like fruit, but I’m thinking people will perceive it as the fruit having gone bad.

Have you tried to carbonate fruit with nitrous?

No, I haven’t. I doubt you would even perceive it; it may be a little effervescent, but most carbonated fruit that I’ve had doesn’t have the wallop that you would get from a good glass of seltzer.

Is the psi [pounds per square inch] you use for your experiments pretty much industry standard? Is the seltzer what I can buy at the store next door?

Well, it’s higher than naturally sparkling mineral water. I had to go to Italy over the summer, and one of the worst things about the trip was that everything was freaking leggermente frizzante, and I was like, can I have molto freaking frizzante? You know, molto molto frizzante? I like bubbles! I want my throat ripped apart. I grew up drinking mixers, like tonic water, which are over-carbonated because you’re going to add them to alcohol.

Especially if you’re an American in Italy, you need it to cut that Campari apart.

I will admit that wines, if you over-carbonate them, lose their balance entirely. And it’s very small changes in pressure that make them go from being delicious to the fruit getting blown out, over-accentuating the oak, or when certain volatiles get over-amplified by the actual bursting of bubbles.

They are getting pushed out.

Flat champagne tends to have no volatiles at all.

Have you ever tried to recarbonate champagne?

Yes. One of the experiments we’ll do in the class here led by food chemist and author Harold McGee is that we’ll get a bunch of bottles of bubbly, and I’ll flatten them in the vacuum machine. I don’t lose too many volatiles because I’ll do it very quickly, and that gives us a baseline. Now, you almost never get to taste actual champagne baseline—you could taste the base before it goes through the champagne process, but it undergoes a secondary fermentation to get the carbonation in the bottle, plus they add a dosage, so you’re really not tasting what the wine would taste like if it were just flat. And if we left it out to go flat, it would just oxidize. So we just put it in the vacuum and forty-five seconds later I have flat. And then we recarbonate to different levels, so you taste what’s happening to the champagne, and then you realize that one of the reasons that people tend not to like American sparkling wines as much is that they are over-carbonated—if they just had a slightly lower carbonation, you’d have more balance. Typical old-school champagne is highly carbonated, but it sits around longer and vents more carbonation out through its corks.

There’s a book, Uncorked, on the science of champagne, and it notes that different grapes and yeasts affect the bubble size and the surface activity of the liquid. That said, for a given liquid, aside from factors with the site of nucleation [where bubbles originate], the bubble size is strictly dependent on the amount of CO2 present. A tiny bubble indicates an older wine: CO2 has leaked out through the cork, which takes some time. In general, I like big bubbles. I don’t find tiny bubbles to be a quality factor. I think it’s associated with quality in champagne simply because the bubbles get smaller as the champagne ages and because over-carbonated wines—which perhaps a young champagne would be, or a lot of New World sparklers are—tend to be rough and imbalanced simply because they are over-carbonated; it’s not the bubble size, it’s just the over-abundance of CO2.

The ratio of CO2 to liquid.

That’s what’s hurting them. Now, obviously the carbonation in wines is natural, but when you have to force-carbonate something, pressure and temperature become extremely important because it’s the combination that determines how much CO2 you’re putting into your product. People don’t think about the fact that alcohol absorbs more CO2 at a given temperature/pressure than water does. The effect is that you need more pressure to get a carbonated flavor in a drink with higher alcohol content.

To achieve a higher carbonation?

To get that same sense of carbonation. So say you’re carbonating liquids between zero and 1.2 degrees Celsius—ice water temperatures—a good bubbly number for water is thirty psi. That’s good seltzer. To get that same feeling in wine, an average wine from about twelve to fifteen percent alcohol, you’re going to want to be at around thirty-five psi. And in general, you don’t want your wine to be that bubbly, so you’re going to be down around thirty-two, because you want it to be less bubbly than your seltzer. But for a mixed drink, where we’re rocking, say, seventeen to eighteen percent alcohol, you’re talking forty psi. Which is why, if you’re carbonating high-alcohol wines—maybe not wine, but perhaps sake, which is up near the alcohol level of mixed drinks—you need to go five psi higher than the equivalent of wine to get the same perception of bubbles. My standard number for mixed drinks is forty psi.

So the soda I’m adding to my scotch is forty psi, but not the final drink?

Ah yes, that’s a problem, scotch and soda is never bubbly enough for me. Really, if you want to make a scotch and soda and you want to do a decent job, take ice, scotch out of the freezer, and seltzer out of the fridge, and then it will be good. But no one makes a good scotch and soda. You pour scotch on the ice; now you’ve diluted it, which is fine if you’re not drinking it neat. Now you’re adding soda, further diluting the carbonation. And nine out of ten times, they’re using those squat bottles and they’re not in the fridge anyway.

You’ve made some high-alcohol mixtures, carbonated gin for instance. What pressure do you do that at?

You’re playing with two variables there. Because when I’m carbonating a forty percent alcohol drink, a straight shot, first of all, it’s very dangerous for people. Not physically, but carbonation accelerates absorption, so people get hit hard and fast. That said, if you want to do it, you need to serve them much colder than you would a normal drink because with straight shots of gin, vodka, or whatever the base spirit is going to be, you want the temperature down near minus sixteen, eighteen Celsius.

Or it will just bubble out?

No, just so that it doesn’t taste like you’re sipping straight alcohol. It’s only the intrepid drinker, like Audrey Saunders [noted drink inventor], who likes her pink gin warm. Most people want a short shot, they want to knock it back, and if it’s going to be bubbly, they want it to act like a cold drink. We’re usually mimicking a cold drink when we’re doing it. So we were doing a gin and tonic at eighty proof. You want it to be cold, biting, refreshing. You really have to take the temperature way down so that the alcohol perception isn’t so high. And assuming you can balance the sugar and acid at that temperature, when you put in forty psi, which is what I do, I’m putting tons of CO2 in there because at that lower temperature so much more can be dissolved into it.

I used to do it a lot, but now I only really do it for demonstrations. I don’t really think it is something that is feasible—those mixed drink shots are only balanced in a very fine temperature range. As soon as they go outside that range, I wouldn’t serve them anymore. We’ve had this discussion: most classic drinks become classic because they can survive abuse one way or the other—a range of temperatures, a range of dilutions—and still remain balanced.

Do you have any thoughts about Joseph Priestley, the discoverer of carbonation?

There’s a British book and an American book on the history of carbonation and their takes are a little different. The one thing that depresses me about the history of carbonation is that our word seltzer comes from the town Selters in Germany where they actually have natural “seltzer” water and until a couple of decades ago you could buy that water. You can’t anymore, even the stuff that’s labeled isn’t authentic anymore. It’s from another source. I would love to try a bottle of the original seltzer. Our word comes from naturally sparkling water.

Priestley made the first soda water by infusing water he suspended over a brewer’s vat. I’m not sure how he pressurized it. Probably what he did was seal up the fermentation so that the CO2 had nowhere else to go except dissolve back into solution. He liked the taste of it and served it to his friends. He also gave a recipe for making it to the crew for Captain Cook’s second exploratory expedition because he thought it might cure scurvy.

He never made money off of it, never started a business?

No.

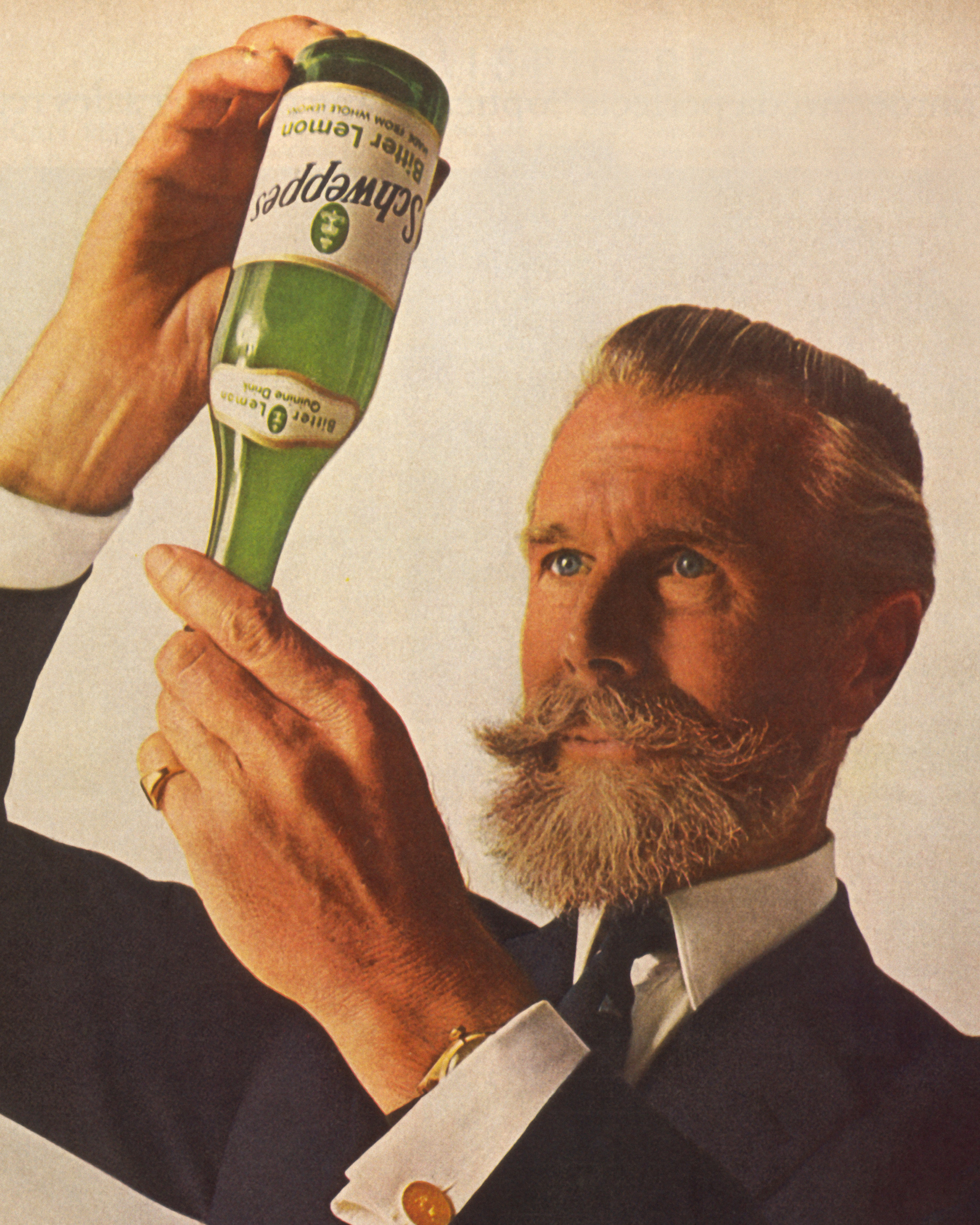

Schweppe wasn’t the first, but he was making it pretty early on.

Priestley was just trying to discover gas. He was one of the co-discoverers of oxygen, too. He called it dephlogisticated air. Any other gases worth carbonating?

Nitrous and CO2 are the ones that I know of that are soluble and provide bubbles. I’m sure we can make a poisonous-smelling one.

Could you carbonate with noble gases?

Well, they won’t dissolve. I mean, you could get someone’s voice to change with helium, but you couldn’t dissolve it.

You could bubble it through while they are drinking it.

You’d have to build a special implement to get it to work.

Like they’re drinking from a fish tank.

That would be kind of neat. Drinking from a fish tank. I’ve always wanted to have a swimming pool filled with seltzer, although it would be quite painful. All your orifices would probably hurt. Imagine opening your mouth and diving into a pool of ice-cold seltzer, for a second you’d be like AHHHH, and then ERRRRR.

David Arnold is the director of culinary technology at the French Culinary Institute in New York City. He began tinkering with restaurant equipment after earning his MFA from Columbia University’s School of the Arts. He has collaborated with many noted chefs, including Wylie Dufresne of wd-50, Johnny Iuzzini of Jean Georges, and food scientist Harold McGee.

Eben Klemm is the senior manager of wine and spirits for B. R. Guest Restaurant Group and the author of The Cocktail Primer (Andrews McMeel Publishing, 2009). Prior to working in the beverage industry, he was a research biologist. He has invented hundreds of cocktails and names as one of his favorites the eponymous Cabinet.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.