Two Bubbles, and a Third

All must inevitably burst

D. Graham Burnett

Have you ever stood at the foot of a waterfall, and marked the bubbles rising to the surface and gathering into foam? Some are quite small, and break as soon as they are born. Others last longer; new ones come to join them, and they swell up to a great size: yet in the end they burst, as surely as the rest; it cannot be otherwise. There you have human life. All men are bubbles, great or small, inflated with the breath of life. Some are destined to last for a brief space, others perish in the very moment of birth: but all must inevitably burst.

The text is one of the more elaborate early sources for the classical commonplace that would become a mainstay of European art and literature: homo bulla—“man is a bubble.” As this austere apothegm drifted out of the stern world of the Stoics and into the fervorous sentimentalism of Christiandom, it became the tear-jerking translucency at the center of human vanity: we are beautiful, delicate, and we die too soon.

As with any metaphor, though, everything depends on the vehicle. We are bubbles? Really? But of what sort, exactly? Charon envisioned the froth on the Styx. Okay, but there are more bubbles under those waters than were dreamed of in his ferryman’s philosophy. Let us consider two of them, in the hopes that contemporary fluid dynamics and marine biology can breathe new life into this hollow allegory.

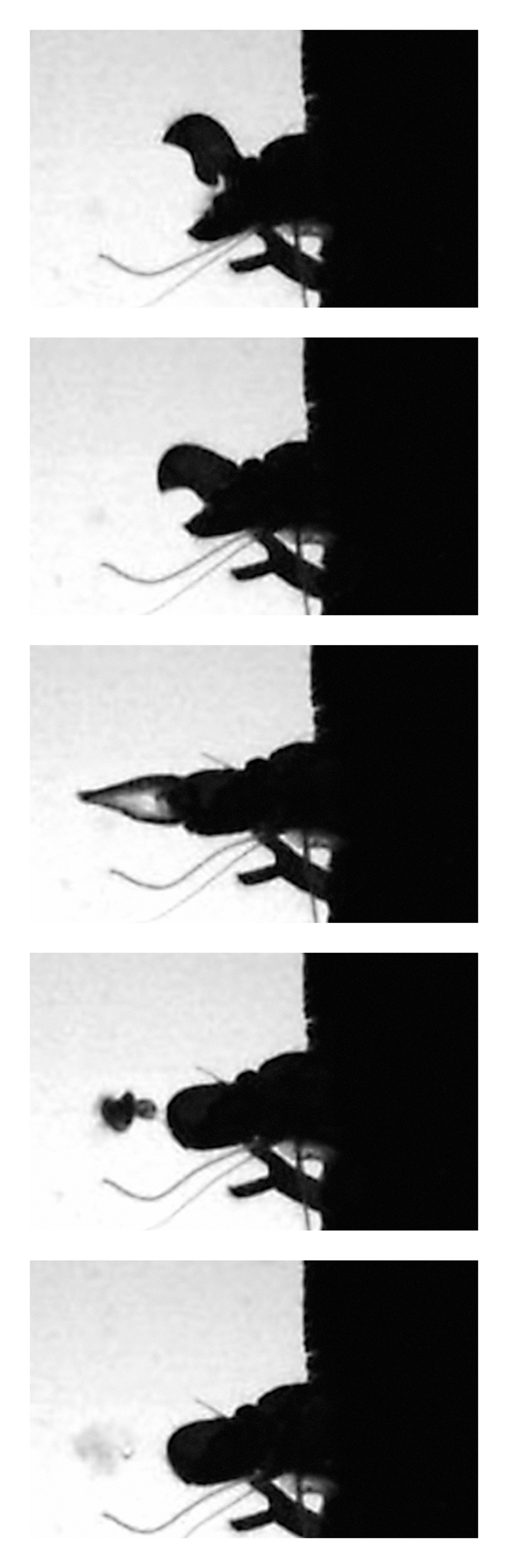

The biologists, however, stayed after the taxon, which was colorful and odd. And their curiosity eventually paid off in one of the very strangest discoveries in modern invertebrate zoology (a field full of extremely weird critters). In September of 2000, a collaborative team of Dutch and German scientists announced that the Alpheidae do not, in fact, make their remarkably loud snapping sound by hammering together their big pincers, as everyone had assumed. Instead, that crack is produced upon the popping of a very unusual bubble that these creatures “blow” by means of a snap of their claw.

So what? Well, this is really no ordinary bubble. Imagine, if you can, a bubble shooting through the water at seventy miles an hour—a bubble the internal temperature of which reaches almost five thousand degrees Celsius, just a smidgen cooler than the surface of the sun. It is a good thing that it is very small.

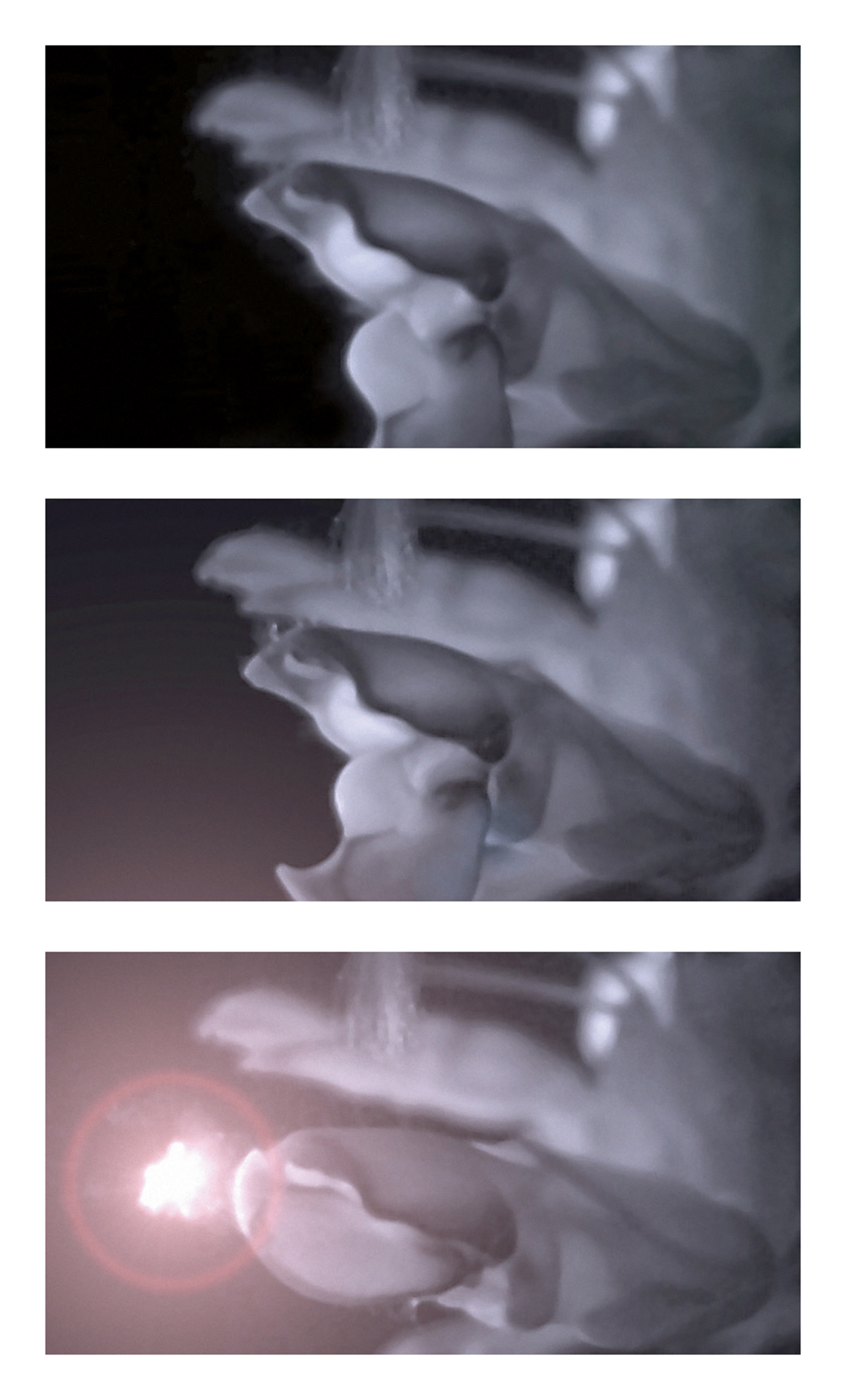

At this point, perhaps predictably, the physicists get interested again, and it is on them that we must rely for an account of this unexpected phenomenon. The bubbles in question are the product of “cavitation,” familiar to naval engineers as a besetting problem for overpowered ships. In essence, if you accelerate water very hard (say, with a propeller), you create a little pocket of suddenly reduced pressure. If this pressure drops sufficiently low with sufficient speed, it can literally cause the water to boil—the pressure plummets below the water’s vapor point, and in a flash you get a rapidly expanding pinpoint of gas, which is to say, a bubble. In fact, the fluid dynamics of the situation are a little more complicated than that, since ordinary water as a rule contains lots and lots of “microbubbles”—invisible tidbits of air. When such a bubblette finds itself in one of these low-pressure zones associated with cavitation, its internal pressure is suddenly out of equilibrium with its surroundings. It swells, creating the “seed” for that explosive vapor-bubble. So under real-world conditions, a cavitation bubble is the product of both these phenomena: a microbubble that gets out of hand, plus sudden underwater irruption of gaseous H2O.

This kind of bubble has been studied intensively for more than a century, since they punch above their weight: the reverberating bang as they rupture creates little shockwaves that, taken together over time, can do real damage to heavy machinery like props, pumps, and gaskets. Thus cavitation is basically enemy number one among fluid dynamicists, torpedo designers, and hydraulic engineers—though in recent years clever inventors have figured out ways to control and use the phenomenon in various cutting and scrubbing tools.

The Alpheidae got there first. Their massive “shooter” claw contains a pair of powerful muscles that can be flexed to cock open their pincer. When they pull the trigger, a plunger-like protuberance snaps into a tight opposing indentation, squirting a jet of water at sufficiently high speeds to generate a nasty, streaking cavitation bubble that tears its way forward, collapsing milliseconds later with sufficient violence that it actually gives off a flash of light. The energies involved are enormous, given the scale: if you could stand right next to such a pop, it would be about as loud as standing directly behind a jet engine—in the neighborhood of 200dB.

And indeed, this is more or less how many Alpheidae use their bubble-shooters: they sneak up on an enemy, or a meal, and blast it. The shockwaves can stun and even kill crabs and fish a good deal larger than the shrimp themselves. There is considerable evidence that they also sometimes use the sound for communication: they speak gunshot.

The thorny matter of dolphin “intelligence” aside, these animals are manifestly quick and sociable, and appear to have their own ideas about things. They are trainable, to be sure, but also a little unpredictable and display a creative independence that sets them apart from many other creatures that will flip over for a food treat. Their capacity to “see” with sound—generating underwater clicks the echoes of which they read for information about their surroundings—put early SONAR systems to shame, and even now the navy keeps a few Tursiops around as underwater bomb-detectors, claiming that there is no hardware that can do the job as well.

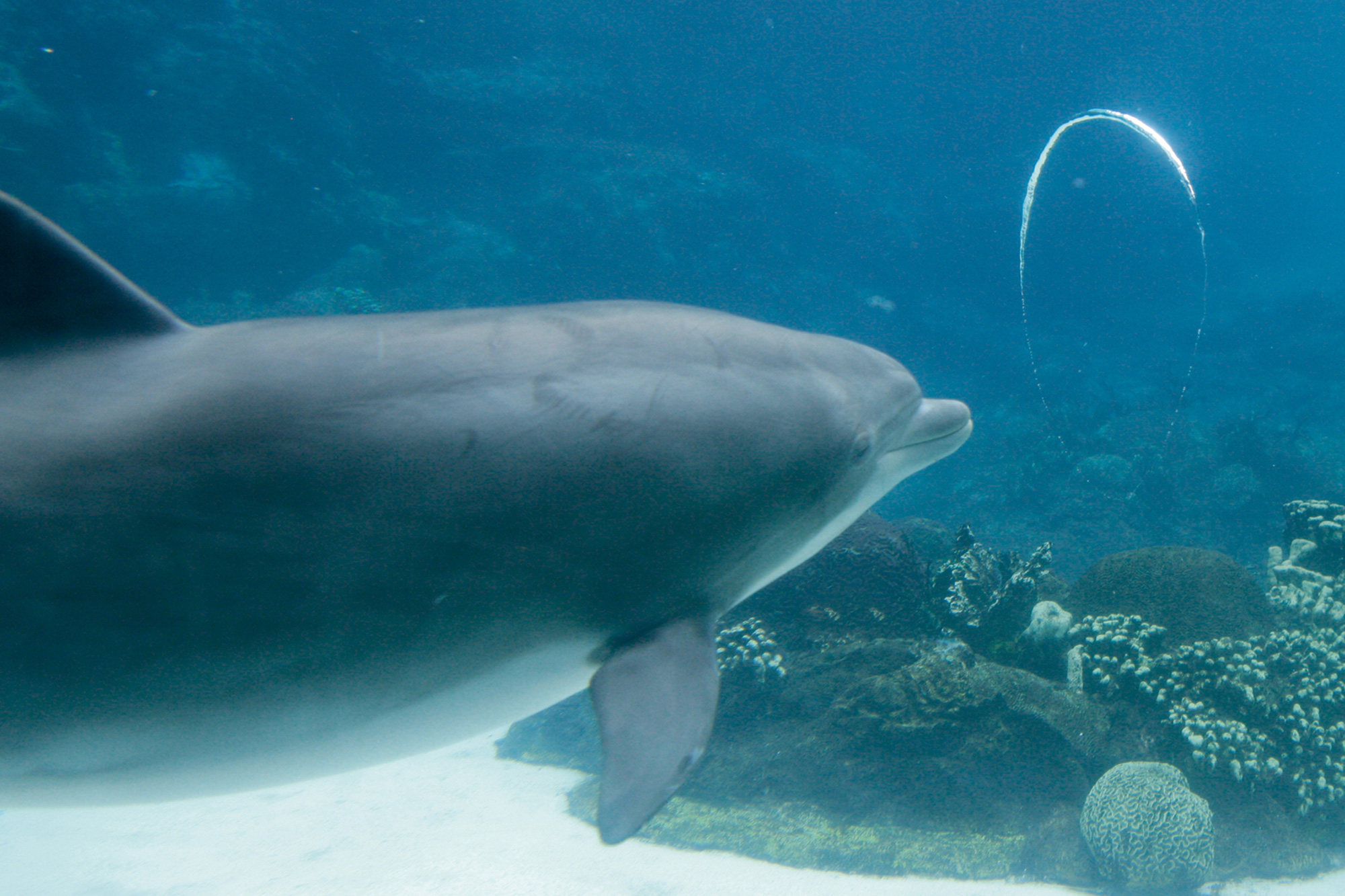

Given that these animals are accustomed to expansive blue-water ranges, it is no real surprise that they can seem bored cooped up in small tanks. But they do entertain themselves. The males have an unfortunate tendency to look for unusual ways to get off (attacking unsuspecting sea-turtles; jamming their cocks into the filtration hoses of the pool), but it is more photogenic when the animals while away their captive hours by blowing breathtaking underwater bubble-rings.

Any good-sized bubble in deep water can suddenly become a doughnut, on account of the higher water pressure on its underside (the pressure goes up as you go deeper). Under the right conditions, this upward thrust will push a bubble-sphere into a kind of mushroom-cap, and then punch through—creating a torus. But Tursiops truncatus have refined this basic physics into a genuinely mind-boggling array of gaseous conjurations and bubble-tricks. And though some of these behaviors have been reinforced by trainers at marine parks for the edification of the crowds, the animals seem not to need much of this sort of encouragement: they appear to do it largely for themselves.

So what do they do? Using their tails and fins, they set up vortices of different shapes and sizes—invisible underwater whirlpools. Then, with carefully timed precision, they lean into these little tornadoes and give an expert puff from their blowholes, blowing perfect rings into the whorl. With this technique some dolphins have figured out how to create shimmering hula hoops as fine as a finger and more than two feet in diameter. And what is genuinely uncanny is that they can get these apparitions to travel horizontally through the water, keeping them going by periodically giving the spin an extra “nudge.” Sometimes they even steer them around corners, or with a peck of their beaks split them in two, or draw them into a spiraling silver helix. Only when entropy is permitted to have its way, and these impossible silver delicacies suddenly vanish in a shower of fizz, can one believe what one has just seen.

I’d like to think so. He points to the wispy froth of the cataract—so fragile, so fated. And we point in turn to a savage jet of cruel heat—an eddy in the chaos, an explosion of sound and light that is both distant speech and instant death. He points to the trembling of a fleck of foam—so transient, so triste. And we point in reply to the radiant belt of a wheeling ring—a necklace worn by the whirlwind, the plaything of a strange, captive god who is at least … amused.

D. Graham Burnett is an editor at Cabinet and a historian of science at Princeton University. He and artist Lisa Young recently collaborated on the video project “Free Fall: The Life and Times of Bud ‘Crosshairs’ Mac-Ginitie.”

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.