Spirit Duplication

Licking wisdom from the purple page

Yara Flores

Every technology is a metaphor. That much is clear. The difficult matter is to sort out whether this is a primary or secondary function. Which is to say, did we initially make this universe of instruments, machines, tools, and devices as a way of talking about our condition, only then to discover, post hoc, that all the amassed hardware also proved useful for solving various practical problems (washing dishes, killing neighbors, etc.)? Or did it work the other way around? Did we set out to kill our neighbors, say, and then notice that the sword was a lovely way to say “violence”?

At first glance, the latter may seem much more likely. But presumably the sword said “violence” before it was swung. If the question feels abstruse, remember that the stakes are high: Are we apes who learned to talk, or angels who learned to kill?

But let me be absolutely concrete. In the late 1970s, at the hands of a small, wiry, and inflexible nun, I received two years of formal catechism at an archaically traditional Catholic school. This meant that every Monday morning we received, each of us in the class, a single sheet of metaphysical dogma laid out in a simple question-answer format. For instance:

A. God made the world.

Q. Where is God?

A. God is everywhere.

Q. What is despair?

A. Despair is the loss of hope in God’s Mercy.

Every Friday we were tested on our mastery of this material, and the tests took the form of precisely the same sheet of paper we had received on Monday from which the “answers” had been erased. We filled them in, writing in blue pen.

Being disciplined, pious, and blessed with a good memory, I received uniformly perfect marks in this exercise, and grew in the satisfactions of tightly defined wisdom.

However, as it happens, between my first and second years of this training my school acquired a new “Xerox” machine, which replaced the old ditto device upon which sister William had long relied. The technologies are very different.

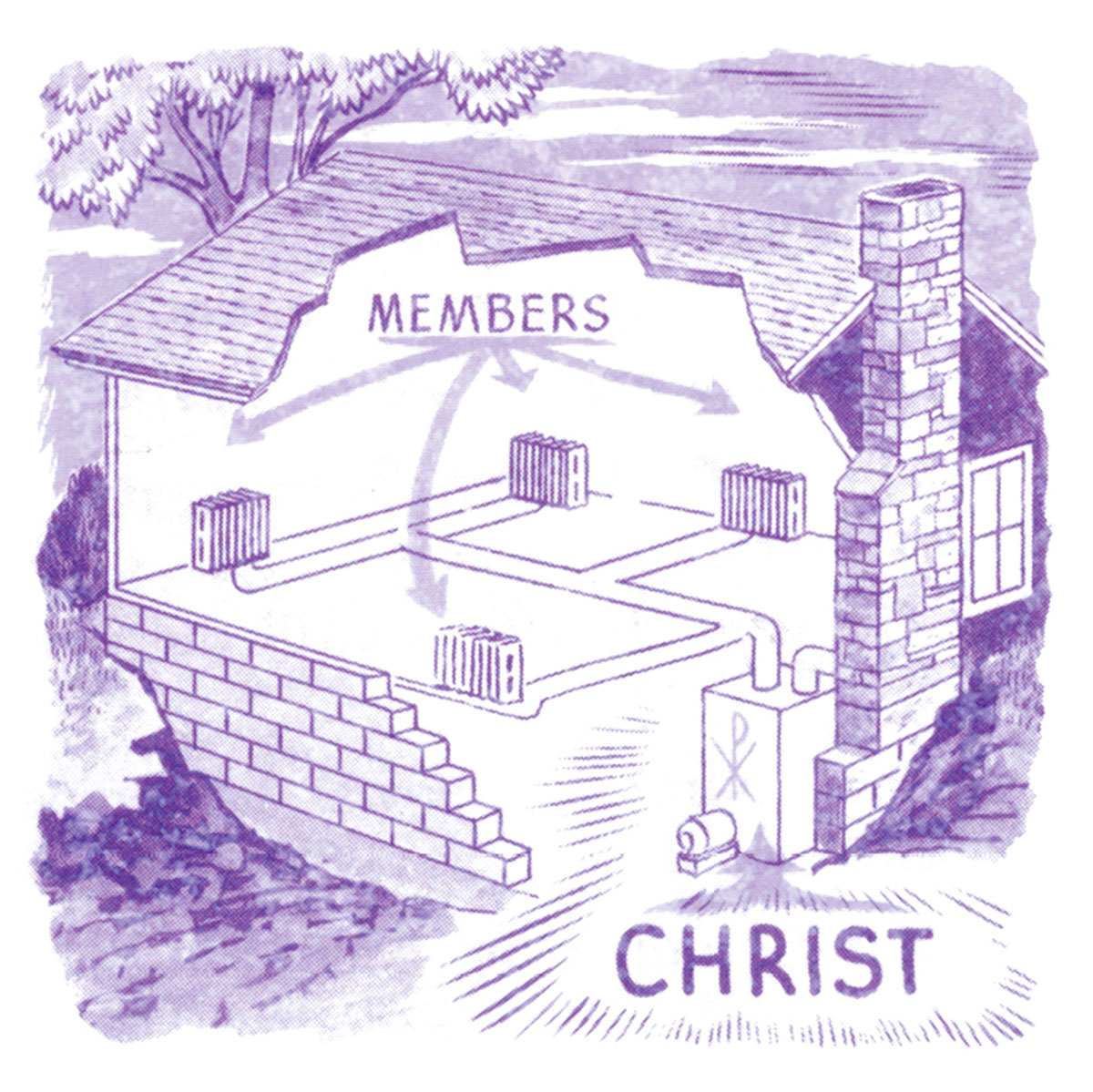

The ditto machine, or “spirit duplicator” as it is more properly known, was a manually cranked drum-printing device originally developed in the 1920s. It worked from a special “master” that looked a little like a piece of carbon paper. This was in fact a sandwich of acetate and a thin tablet of deep purple wax. When you typed or wrote on the master, the wax stuck to the back of the cover page, producing a waxy negative of your original. This was then fixed, wax side out, to the revolving drum. As the machine went to work, the sheets of paper to be printed were individually wetted with a highly volatile mixture of isopropyl alcohol and methanol. Touching the roller, this combustible and intoxicating broth instantly dissolved the colored wax from the master, leaving a purple trace of every word.

Xerographic duplication, by contrast, is an electrostatic process, and makes use of bright light to recreate the original in a pattern of negatively and positively charged regions. A positively charged powder adheres to the negative bits of this pattern, which correspond to the dark parts of the original. Heat cooks this black dust onto the blank page, creating the copy.

I did not like the new copies. There was the disconcerting matter of the powdery toner. One of my first sheets, incompletely fused, vanished at the touch of my finger. Not encouraging, from a catechistical perspective.

But even worse was the dryness. Sheets fresh from the ditto machine came doused with their intoxicating vehicle. They were limp and delicate and heady. One breathed deeply, and felt a lightness of the spirit. Like the page, one was softened to receive the purple words.

By contrast, these strange new handouts were made of static ash, of a nervous kind of soot. They felt brittle, dusty, lifeless. Without the penetrating aroma of naphtha, the dialogic doctrines felt strangely inert. Absent the lurid aniline purple—redolent of both Tyrian splendor and cruel wounds—the blackletter teachings took on a dour formality.

It is very disorienting to go from theology as Eros to theology as Thanatos over a short summer vacation. And I am not sure I ever really recovered.

Which brings us back to the semiotics of technology. In an important book published in English as Metaphors of Memory (2001), the Dutch historian Douwe Draaisma traced the shifting use of concrete referents for our inner life. How does the mind work? Like a block of wax, suggested Plato. Which is to say, it takes an impression. Or, later, the mind was said to be more like a library. Which is to say, you fill it with books. Each of these tropes had significant implications for thinking about pedagogy.

Q. Is the pupil to be molded, incised, or impressed?

A. I don’t know.

Q. Does wisdom shape up in us as ash, fixed by a dry heat? Or do we, soused with an intoxicating liquor, lick it from the purple page?

A. I don’t know.

See press on “Spirit Duplication” in Printeresting and Edit.

Yara Flores was born in Brazil and currently lives in Puerto Rico. She is a poet and graphic artist.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.