The Theater of Forgetting

Scenes of censorship

Peter Galison

Censorship reaches deeply into the psyche. Back in the nineteenth century, Russian frontier guards ferociously blotted out references in imported literature that might stir anger about the legitimacy, stability, or longevity of the Tsars. Without unwanted prompts, the populace might forget about the paternity of Catherine’s children, or that assassins had been bringing down Russian rulers for centuries. Memory, even fictional memory (or so the fear went), might provoke revolution. With glue, paper, and liberal amounts of black ink (known, because of its color and form, as “caviar”) the border guards annihilated offending sentences—targeting with special vigor German-language texts. To Freud, writing in Vienna, the Russian censor with his black ink and papier mâché stick-ons was, from early on, a more-than-metaphor for our unconscious rubbing out of disturbing memories, dreams, and thoughts.

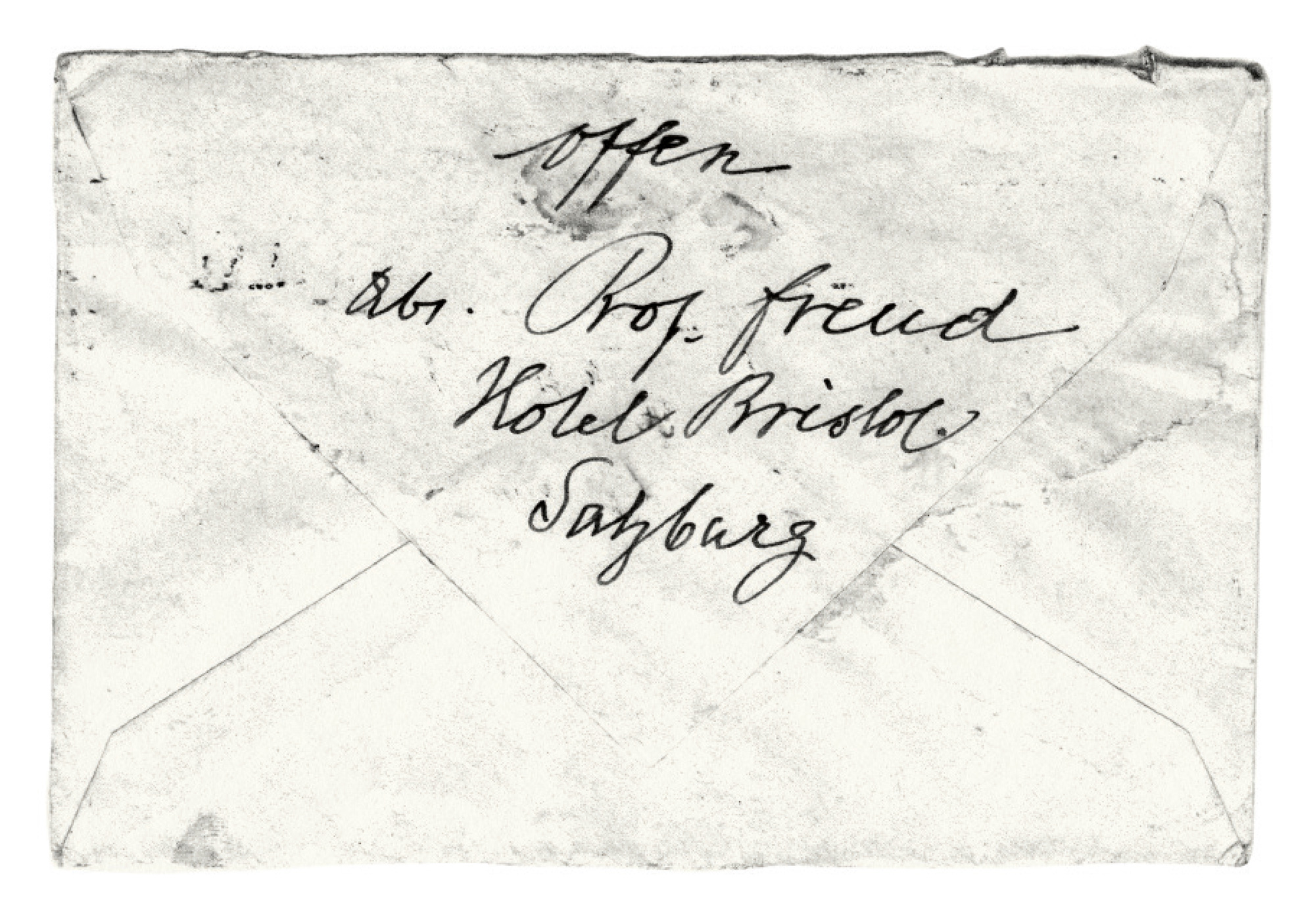

Censorship drew closer. During World War I, it descended on Vienna itself, like a great smothering blanket. Newspapers, especially on the socialist left, felt the brunt of the censors’ wrath on a daily basis. Editors and writers would finish their composition of the day’s news, and then, too late for re-writing, the censor would slash bits—sometimes a sentence, sometimes a paragraph, sometimes an entire article. Viennese police censors, some three thousand of them, also monitored correspondence—and not just to the front.

It was in such a climate that the international socialist militant Friedrich Adler agitated against the war, polemicizing in his monthly Der Kampf—until it was censored and shut down by the authorities. Adler, for years the secretary general of the Austrian Socialist Party, was the son of Victor Adler, who, in addition to being the head of the Austrian socialist movement, was a psychiatrist who knew Freud. (Freud actually recorded a dream he had about Adler senior in his Interpretation of Dreams.) Young Adler (“Fritz”) had begun his career as a physicist—and was one of Albert Einstein’s closest friends from their university days in Zurich, where they had shared classes and even been housemates during some of Einstein’s crucial scientific years.

For Fritz Adler, censorship was one of the worst infringements on Austria’s halting struggle toward democracy, along with impediments to free assembly and to the convocation of parliament. Censorship was an obstacle to the political passage, so Adler believed, out of Austria’s autocratic, imperial past. On 20 October 1916, the Arbeiter-Zeitung, the Socialist Party newspaper founded and edited by Victor Adler, laid out a screed against deleting news on its front page. In bold black print, the headline read: “Censorship.” But the article itself was censored. Between censorship and autocratic interference with deliberation more generally, Fritz Adler had had enough. He believed that the prime minister of Austria, Count Karl Stürgkh, was behind the constant interference with democratic action. And in the case of this article we actually can know what was behind the curtain, so to speak. The blocked bit (as I know from an unmolested version of that day’s paper that survives in the Socialist Party’s archives) began: “No one has been successful in moving Count Stürgkh—he who is indeed the originator of the whole system designed to abolish press freedom—to actually speak.” A few hours later, on 21 October, Adler took his Browning pistol, faced the prime minister at the Meissl and Schadn Hotel, and killed him. Einstein leapt to his friend’s defense—it became one of the Austria’s most sensational trials.