Historical Amnesias: An Interview with Paul Connerton

Seven types of forgetting

Jeffrey Kastner, Sina Najafi, and Paul Connerton

In The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, Milan Kundera wrote: “The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.” This perspective—one that bears the marks of life under a totalitarian regime in which repression often took the form of enforced forgetting—assumes that remembering is always a virtue and that not doing so is necessarily a failing. But despite dominating much of the debate on cultural memory, this perspective elides the many differences between all the various acts that we cluster under the term “forgetting.” Are all acts of forgetting similar enough that we can think of them, always and necessarily, as a failure? Can forgetting in fact even be a virtue? And how do we understand the relationship between what needs to be forgotten in order for other things to be remembered?

Paul Connerton, a scholar in the Department of Social Anthropology at the University of Cambridge, has addressed these issues in a number of books, including How Societies Remember (Cambridge University Press, 1989) and How Modernity Forgets (Cambridge University Press, 2009). In his 2008 essay “Seven Types of Forgetting,” Connerton offers a preliminary taxonomy of forgetting, and of its various functions, values, and agents: repressive erasure; prescriptive forgetting; forgetting that is constitutive in the formation of a new identity; structural amnesia; forgetting as annulment; forgetting as planned obsolescence; and forgetting as humiliated silence. Jeffrey Kastner and Sina Najafi spoke to Connerton by phone.

Cabinet: We first discovered your work through your essay “Seven Types of Forgetting.” But you’re perhaps best known as one of the leading scholars in the field of memory studies. Tell us a bit about memory studies—what does it mean; where does it come from?

Paul Connerton: In some sense, memory studies is really a phenomenon of the last quarter century. One hundred years ago, there would have, of course, been studies of memory—by Freud, by Bergson, by Proust—but they would have been primarily interested in individual memory. What’s happened in the last quarter century has been a turn toward cultural memory. And because of this turn, the term memory studies has acquired currency.

The curious thing is this: although there has been an enormous proliferation of work on memory studies in the last quarter century—not only in English, but also in French, German, and Italian—it seems to me rather strange that no one has really set out to explain why exactly during this particular historical period, from 1980 or so on, there has been such an obsession with memory studies. I don’t think this can be understood via any single factor, but it could possibly be explained by the confluence of three powerful forces coming together. The first could be described as the long shadow of World War II, which continued to exert its impact even as late as the 1990s. Think for example of the celebrations in 1995 of the fiftieth anniversary of the end of World War II. Another factor in the emergence of memory studies has been what I would call “transitional justice.” And by that I mean to say that in the 1980s and 1990s there were transformations in various countries—in Argentina, Chile, El Salvador, South Africa, in the states of central eastern Europe—that had had a very difficult past, on the whole a totalitarian or authoritarian past, and had moved toward a more democratic form of government. Precisely because they had had a difficult past, they had to take up a position about it, they had to examine their memories. They had to think about what attitude they should take toward the previous perpetrators and victims of injustice. And the final significant factor has been the process of decolonization, which had very significant repercussions—not only for the previous colonizing powers, in particular Britain and France—but also for the previously colonized powers, in particular Africa and India, who have sought, so to speak, to reappropriate their own memories, whereas for the previous colonizing powers, what has emerged is what might be described as a politics of nostalgia. In fact, the famous three-volume work edited by Pierre Nora, Realms of Memory, is an interesting case in this regard because although it is presented as a gigantic and cooperative academic exercise, it seems to me that there is a very powerful undercurrent of nostalgia in that volume.

What is the difference between doing memory studies and doing history?

We need to distinguish cultural memory from historical reconstruction. Knowledge of all human activities in the past is possible only through knowledge of their traces. It might be the bones buried in Roman fortifications, or a pile of stones that is all that remains of a Norman tower, or a word in a Greek inscription whose use reveals a custom: in all these cases what the historian deals with are traces, that is to say, the marks which some phenomenon has left behind. Simply to apprehend these marks as traces of something is to have gone beyond the stage of making statements about the marks themselves; to consider something as evidence is to make a statement about something else, that is to say about that for which it is taken as evidence.

Historians, in other words, investigate evidence in much the same way as lawyers cross-question witnesses in a court; they extract from that evidence information which it does not explicitly contain or even information which was contrary to the overt assertions contained in it. Historians are able to reject something explicitly told to them in their evidence and to substitute their own interpretation of events in its place. And even if they do accept what a previous statement tells them, they do this not because that statement exists but because that statement is judged to satisfy the historian’s criteria of historical truth. Far from relying on authorities other than themselves, historians are their own authority; their thought is autonomous vis-à-vis their evidence, in the sense that they possess criteria by reference to which that evidence is criticized. Historical reconstruction is therefore not dependent on social memory. It is autonomous with regard to social memory. This, I would say, is the fundamental difference between doing history and doing memory studies.

Perhaps we can go back to the roots of the premise that you take up and critique in your work: namely, that remembering and commemorating are always understood to be virtues. Where does this idea come from? Is it a modern idea? Does it come with the rise of history as a discipline itself?

I believe it has come about as a result of the particular political history of the recent era. I think that coerced forgetting was one of the most malign features of the twentieth century. For example, think of Germany after Hitler, or Spain after Franco, or Greece after the colonels, or Argentina after the generals, or Chile after Pinochet: in all these cases, there had been a process of coerced forgetting during the dictatorships. And if, on the other hand, you think of some the distinguished writers of the second half of the twentieth century—Primo Levi or Alexander Solzhenitsyn or Nadezhda Mandelstam—the interesting thing about them is that they took up their pens in order to combat this process of coerced forgetting. As a result of this, I think that you could say that at the end of the twentieth century there was such a thing as an ethics of memory. Memory and remembrance had acquired the quality of an ethical value.

This ethics serves as an antidote to repressive erasure, which is in fact the first kind of type of forgetting that you address in your essay.

Yes. And you can say that there’s an ethics of memory at the end of the of twentieth century in a way that I don’t think is there at the end of nineteenth or eighteenth or seventeenth centuries, and that is precisely because totalitarian regimes engaged in such severe and punitive processes of repressive erasure in the twentieth century. And remembering in this sense thus has acquired the quality of a countermovement or retrieval.

But this notion that everything must be remembered seems to have been in place already in some form in the nineteenth century, since Nietzsche is already critiquing it in “The Use and Abuse of History,” in which he addresses what you call the “excess of historical consciousness.” For him, “the repugnant spectacle of a blind lust for collecting, of a restless gathering up of everything that once was” creates a situation in which “man envelops himself in an odor of decay.”I don’t think that Nietzsche thought about this in terms of an ethics. When I discuss him, I do it in the section that addresses what I call “forgetting as annulment.” And I think that the important thing here is that forgetting as annulment results from the problems arising from a surfeit of information. Of course, Nietzsche wasn’t the only one to have done this. Hundreds of years earlier, for instance, Rabelais’s Gargantua and Patagruel includes an extremely amusing passage in which he describes how his hero Gargantua has his brain completely clogged up with information coming from his scholastic learning. So his doctor gives him a particular kind of potion which causes him to sneeze, and when he does, all the superfluous scholastic knowledge that is blocking up his thinking comes tumbling out of his brain and, as a result of this, he’s able to think clearly. And of course the idea of forgetting as annulment can also be related to Thomas Kuhn’s notion of a scientific paradigm, which for him is in some sense about forgetting. Kuhn’s idea is, among other things, that people who have presented new ideas in the natural sciences have either been very young or they have been new to the area of science where they had presented these innovative ideas. In other words, their minds have not been too clogged up with scientific memory.

Forgetting as annulment isn’t the only category in which you characterize forgetting in a positive context.

That’s right. Take prescriptive forgetting, for instance. At various time there have been, normally as the action of governments, edicts that have effectively stated that it is inadvisable to remember, and it is recommended that people forget. And this is because it was felt that national or international conflicts had created so much bad blood that the best thing to do was simply try to forget them. In contrast to the twentieth century, where the treaty of Versailles in 1919 left the Germans with a terrible memory of punitive sanctions against them, many earlier conflicts were characterized by a quite explicit attempt to forget the previous animosity. For example, the treaty of Westphalia of 1648, which brought an end to the Thirty Years’ War in Europe, contained as its second clause the requirement that the previous warring parties should not only forgive, but should also forget, all the damage that had been inflicted during those thirty years. And when Louis XVIII came to the throne in France in 1814, he wanted to bring to a conclusion all the civil unrest unleashed by the French revolution. And so he commanded that there be no investigation of events between 1789 and 1814, simply because he didn’t want the anger and the vendettas that might have been caused by continuing to think about this. And just to cite one final example of prescriptive forgetting, the ancient Greeks were particularly aware of this danger of remembering—of chains of vengeance just going on and on—and in fact they built, in their main temple on the Acropolis, an altar to Lethe, the goddess of forgetting, on the grounds that the life of the city-state was actually dependent on forgetting.

This type of salutary forgetting also operates on the level of the individual in your scheme.

Yes, in what I call forgetting that is constitutive in the formation of a new identity. What I mean by that is if a person undergoes a transition to some new kind of identity—a new form of sexual identity, say, or political attachment—it would often be deleterious for them to think too seriously or too long about their previous attachments. So the best thing might be to discard these memories that wouldn’t serve any practical purpose in the ongoing life of the present. To think too closely about their previous attachment would bring about too much cognitive dissonance in terms of how their memories of the past related to their ongoing practices in the present. Just think of Saint Augustine—think about the amount of cognitive dissonance that that poor fellow would have had to endure if he had thought too long about his earlier life.

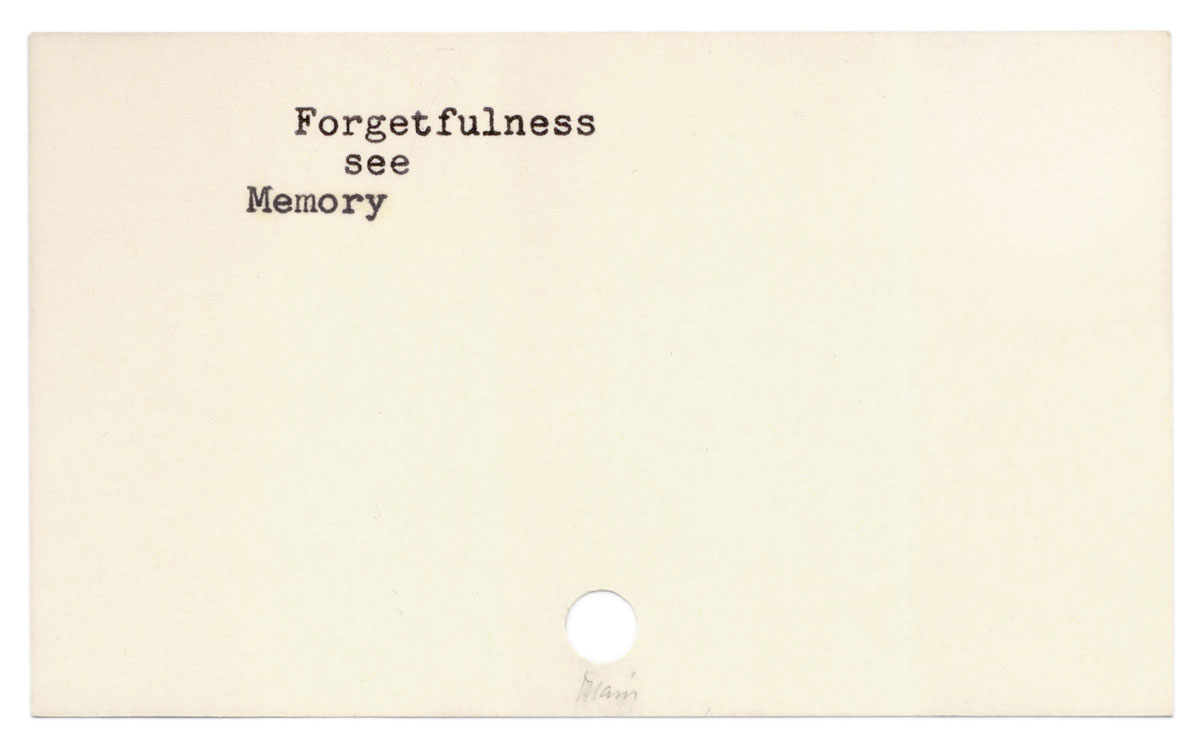

When you were talking about prescriptive forgetting, you mentioned the Greeks and that early moment where forgetting and forgiving were explicitly connected—in that context, it’s interesting to think about the etymological relationship between the words amnesia and amnesty. But you also write about the evolution of other words related to memory and forgetting, and in particular how long-term cultural forgetting as a process of discarding is shown in the appearance of some new words in modernity and the suppression or loss of some others. These new words include revolution, liberalism, and socialism, as well as history and modernity themselves, while we’ve lost words like memorous (memorable), memorious (having a good memory), memorist (one who prompts the return of memories), and mnemonize (to memorize). Perhaps this goes back to the question we posed earlier about the relationship between history and memory studies—the notion that perhaps we have not lost this sense of memory but instead have actually expanded it, refined it, and understood it differently. And now we have a different word for memory: namely, history.

Well, the period when these terms come into use is roughly speaking between 1780 and 1830, and it’s right that the term history came into use in the current sense in that same period. But it’s important to make a distinction between two uses of the word history. One use of it refers to a formal inquiry, the activity that historians do, history in the plural—the history of Charles V; the history of Caesar; the history of the decline and fall of the Roman Empire. But in the period between 1780 and 1830, what emerged was the idea of history as a collective singular, in other words the idea of history as a meta-narrative, a notion which simply didn’t exist before 1780. So this idea that there is some kind of story common to all of us belongs together with these other terms like revolution and liberalism and socialism and modernity, and probably nation and nationhood, as well.

It might be that an important factor in the emergence of all this was the period of Napoleon’s rule in France and the Napoleonic wars. The sweep of his military campaigns throughout central Europe and even as far as Russia brought many soldiers into a hugely widespread area of activity and left a deep impact upon people’s sense that we might all be sharing in something together.

And what about these memory-related words that declined? Why were they no longer adequate for structures of feeling that we had at the time?

I think that with the development of printing, the nature of memory undergoes a huge change. Let me take a few steps back, actually quite a few, to try to explain what I mean by this. There was a Greek musician and poet, Simonides, who attended a dinner party—the roof collapsed when he was out of the room, and everyone was crushed, making it impossible to identify them. When Simonides returned, he discovered that if he focused his attention on certain parts of the room, like the corners or the columns or the ends of tables, he was able to remember who had been where at the party. And this of course became the (probably apocryphal) beginning of a particular art of memory—the “memory palace”—which lasted for about 1,800 years, roughly speaking from Cicero right through to Leibniz, until the middle of the eighteenth century. This process of remembering was used not by the majority of people, but by politicians, lawyers, and ecclesiastics—basically people who needed to remember long sequences of thought. And they needed therefore to mentally place the items in the sequence in certain parts of their memory building. This whole process was crucial for the functioning of memory for many, many years. But by the end of the eighteenth century, because of the proliferation of printing, the exercise of this particular skill of memory—visualized memory—was no longer necessary, because you could look things up. And because of this fact, these words ceased to be as important. I think they were all really clustered around this particular skill in memory. And, by the way, I do think there are certain activities in which people who have never heard of this tradition actually use this technique, even now. Two groups that come to mind immediately are taxi drivers and waiters and waitresses, both of whom have to have quite sophisticated ways of thinking about information spatially. So it’s not necessarily an elite capacity; it can be a quite everyday one.

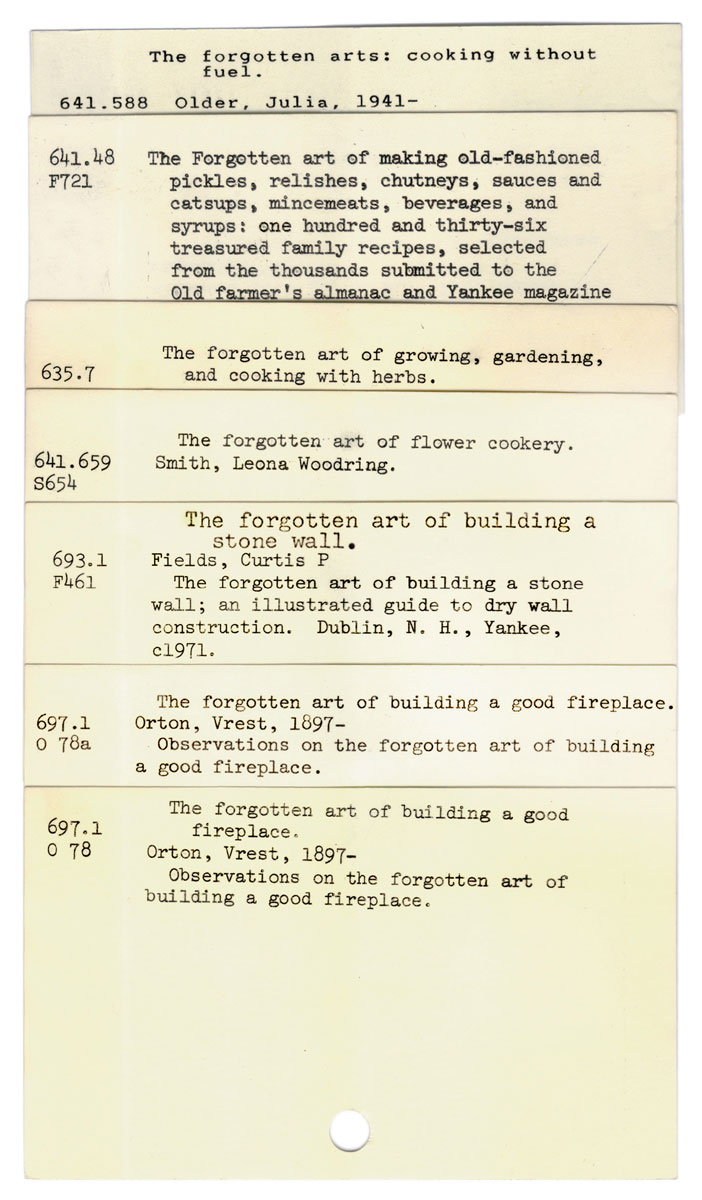

Food is also one of your primary examples when you discuss “structural amnesia.” This was originally a term from anthropology indicating that a person tends to remember only those links in his or her pedigree that are socially important; for example, in strongly patrilineal societies, matrilineal ancestors are forgotten. In the case of cuisine, you argue that the rise of printing has had a profound impact on the way individuals remember and forget recipes handed down across generations.

Well, when you have cookbooks you can have an infinite variety of cuisines, whereas without them you are entirely dependent on remembering what grandmother or mother did. The availability of printing systematically affects which recipes can be transmitted and which are forgotten.

And the rise of printing is not the only technological phenomenon that you implicate in the process of forgetting—you also discuss the notion of planned obsolescence, shifts in industrial culture, and the relationship of these to modes of forgetting and discarding.

Yes, this is brought about by the particular stage we’ve reached in modern capitalism. I think that it can be summarized quite simply by saying that there has been a movement from the production of goods to the production of services, in other words instead of consumer durables like cars and refrigerators, what you get is the production of services. One of the effects of this shift in the focus of production is the speeding up of the turnover time of capital, which helps the process of the production of profit. But of course a side effect of this is to speed up the experience of time, and by speeding up time to bring about situations where forgetting is enhanced. Forgetting is absolutely crucial to the operation of this kind of obsolescence and absolutely basic to the functioning of the market.

If I may, though, I’d like to return to food briefly, which is very interestingly related to both remembering and forgetting. You would think that there is a very powerful connection between food and remembering—you get this in the New Testament, in the Christian liturgy, where eating is explicitly enjoined on believers as a way of remembering. And the Trobriand islanders, for instance, believe that memory is located in the stomach. And then there are fascinating works by Heinrich Böll, temporally located during World War II or in the immediate aftermath, that are about memories of hunger—his novel The Bread of Those Early Years and the short story “That Time We Were in Odessa,” for example—that evoke very powerfully the connection between hunger and memory.

But in fact whereas you would naturally think that food is connected with remembering rather than forgetting, it ain’t necessarily so—there are some interesting connections between food and forgetting. For example, if you think of people who lose contact with family or community, this often takes the form of forgetting a particular set of tastes. And anthropologists have worked on what they call “mortuary feasting,” that’s to say a form of ritual eating after death that’s intended to bring about what’s called “phased closure,” an ending to a relationship via a form of ceremonial forgetting. So the relationship between food, remembering, and forgetting can be an extremely complex one.

You mention Heinrich Böll, whose account of Germany’s wartime destruction might be understood as a rare exception to another of your categories, namely forgetting as humiliated silence.

Humiliated silence as a form of forgetting seems paradoxical, since I think you could argue that it’s more difficult to forget a humiliation than it is to forget physical pain. The German economic miracle after World War II is an important example for this type of humiliated forgetting. I think the devastation that the German people found themselves surrounded by was a constant reminder of the question of whether they were not, in fact, guilty of bringing all this on themselves, and of course a reminder of the colossal devastation to people, to personal relationships, and so on. People have talked about the economic miracle of the rebuilding of Germany as an astonishing phenomenon, and it certainly was, but one thing that has been less discussed is the fact that the frantic and, you might even say, manic effort that went into this economic restructuring was probably driven, whether consciously or unconsciously, by a desire to forget the immediate past. The devastation was a constant reminder of their humiliation and therefore the faster that could eliminate it, the faster they might hope to forget their humiliation.

It seems like the question is how to calibrate forgetting so that it in fact has value for proceeding to the next phase of history. It’s almost like mourning—if it’s done too quickly, in the wrong way, it might come back to haunt you. For example in the case of Germany’s relationship to the past, attempts to forget the past occured in ways that did not really allow the Germans to process the events of the war properly and so, in the last few decades, a number of books have come out that detail some of the after-effects of what you call “manic” forgetting. So there seems to be forgetting that has value because it’s done in the right way, at the right pace, in the right context. And then there seems to be ways of trying to forget the past that come back to cause real problems for the nation in question.

Germany is a very interesting case of forgetting, because the 1968 student revolutions there were quite different, in my opinion, from the student revolutions in other European counties. In France and Italy you did have rebellions, but this didn’t bring about the kind of generational break that it did in Germany, where the students who were involved in rebellions often spoke with indifference or contempt toward their parents. I think this arose out of the fact that their parents never spoke to them about the past, so it was an unshared past, a set of unshared memories. In fact there was a whole genre of books that came out in the 1970s in Germany called “the literature of fathers,” which was all about the mourning for the lack of relationship with the father. They’re a strange combination of a precocious autobiography of the young person and a very extensive obituary of the father—these two features are pulled together to produce what might be called a historical report.

Paul Connerton is a research associate in the Department of Social Anthropology at the University of Cambridge. His books include How Societies Remember (Cambridge University Press, 1989), How Modernity Forgets (Cambridge University Press, 2009), and The Spirit of Mourning: History, Memory and the Body (Cambridge University Press, 2011).

Jeffrey Kastner is senior editor of Cabinet.

Sina Najafi is editor-in-chief of Cabinet.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.