Winter 2011-2012

Inventory / To Do

Scripting the self

Molly Gottstauk

“Inventory” is a column that examines or presents a list, catalogue, or register.

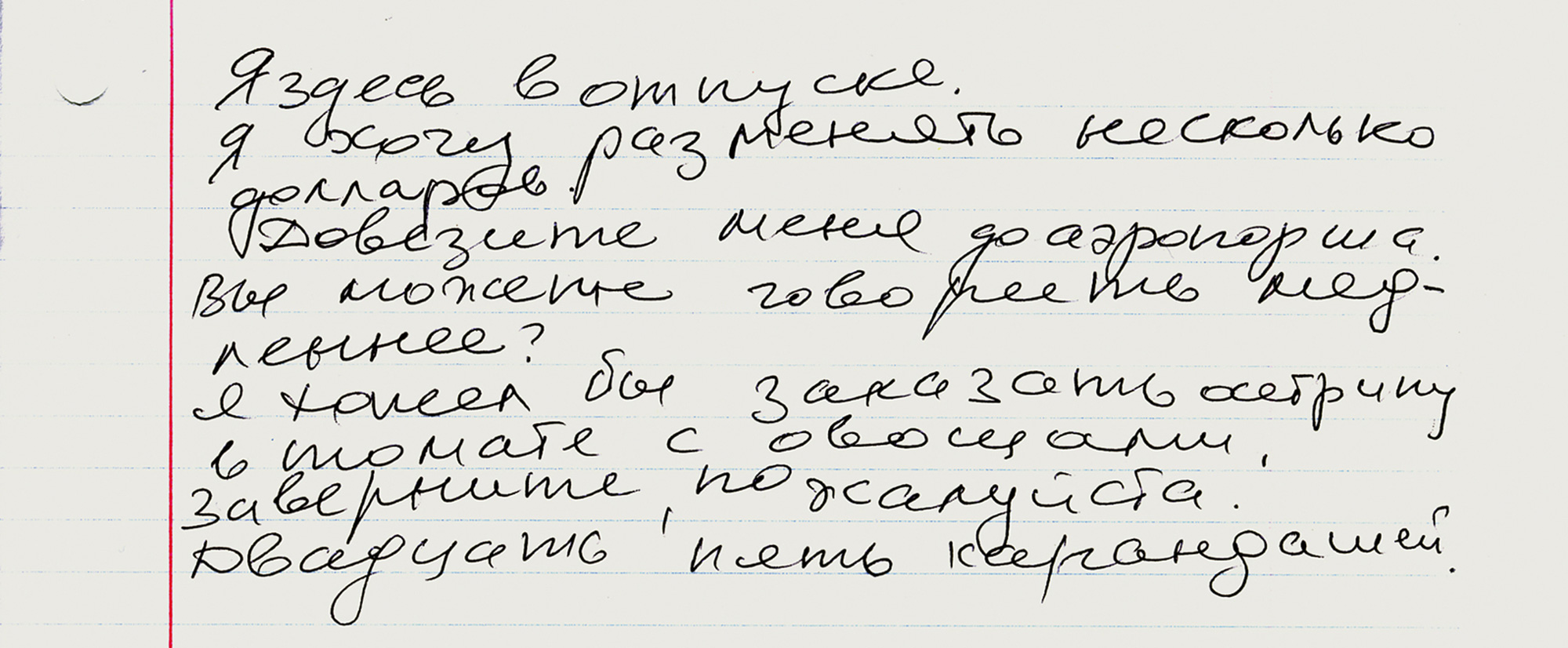

Nikita Khrushchev’s purported to-do list, 25 October 1962. Thanks to the Rostovskys for additional research.

INTRODUCTION

In 1988, the Archives Division of the University of Oklahoma Library came into possession, by deeded gift, of an unusual private collection: about three thousand manuscript “to-do” lists in various languages, dating from the ninth to the twentieth century, and ostensibly representing holograph material penned by various significant historical personages (Duns Scotus, Walt Whitman, Napoleon, Spinoza, Catherine the Great, Benjamin Franklin, Garibaldi, etc.). Questions were raised from the outset concerning the provenance and authenticity of a number of these documents, and cataloging was delayed, pending proper research. As an assistant to the rare books curator at the time, I inherited the problem, and have worked on it intermittently since, as other obligations allowed. This brief essay represents a preliminary report on my findings, together with an invitation to interested parties who might wish to consult the collection (The Cherwitt Sangster Repository for the History of Self-Organization), now open to the public for the first time.

CONTEXT AND CONSIDERATIONSThe last decade has seen a burst of interest in lists in general, and a flurry of attention to the to-do list more specifically.

Cabinet’s own “Inventory” column certainly merits mention in connection with this trend. Theoretical and artistic enthusiasm for the genre would seem lately to have reached a fever pitch. In 2009, the distinguished Italian semiotician Umberto Eco presided over a veritable list extravaganza at the Louvre—a year-long series of exhibitions, lectures, and projects that interrogated the form in a host of poetic and practical

instances.[1] Shortly thereafter, the Smithsonian curator Liza Kirwin mounted a smaller, similarly themed show at the Morgan Library in New York

City.[2] While both of these undertakings included discussions of to-do lists, each reached well beyond that idiosyncratic corner of the larger world of paratactical enumeration. The to-do list per se in fact found its muse back in 2007, when the writer Sasha Cagen gave the world a spirited reading of her own collation of such documents, culled from friends, correspondents, and readers of her short-lived

To-Do List magazine. Unfortunately, a quirky idiom of self-help psychology (and a lowbrow appetite for the voyeuristic aspects of these ephemera) marred her book project, and prevented Cagen from a much-needed delving on the larger historical, political, and philosophical questions at

issue.[3]