Law and Odor

Scent as a chemical weapon

Ned Beauman

Earlier this year, a Wisconsin medical examiner was charged with stealing part of a human spine that she’d intended to use to train her dog to sniff out murder victims. She could have saved herself a lot of trouble by spending $57 on her credit card. In the online store of the Sigma-Aldrich Corporation—which sounds like the villain in a cyberpunk novel, but is in fact just a multinational science company—you can find three different products intended to simulate the smell of a rotting body: one for the early stages of decomposition, one for the late stages of decomposition, and one for decomposition under water. They were developed in 1990 by chemists Thomas Juehne and John Revell, who had already delighted police canine handlers by working out how to fake the smells of heroin, cocaine, and marijuana. Until the release of the Sigma Pseudo Corpse Scent line, these handlers had been accustomed to using soil collected from underneath a cadaver, which is apparently an unpleasant thing to keep in your office (although still pretty innocuous compared to a pilfered human spine). It’s strange to think of laboratories devoted to imitating the worst stenches known to man, like some sort of dark mirror of the perfume business—but in fact this is a growing niche industry with a surprising number of customers, nearly all of them in uniform.

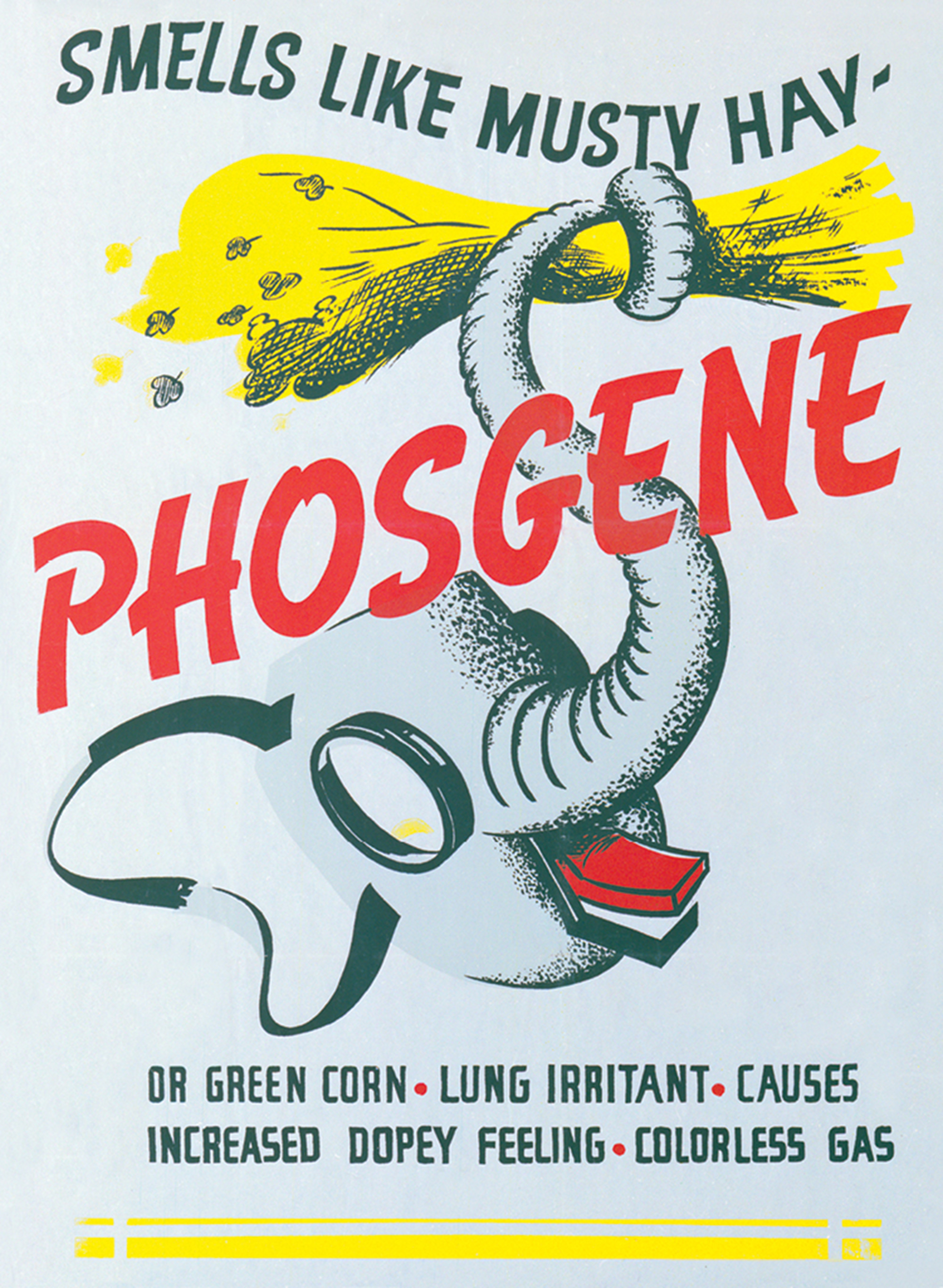

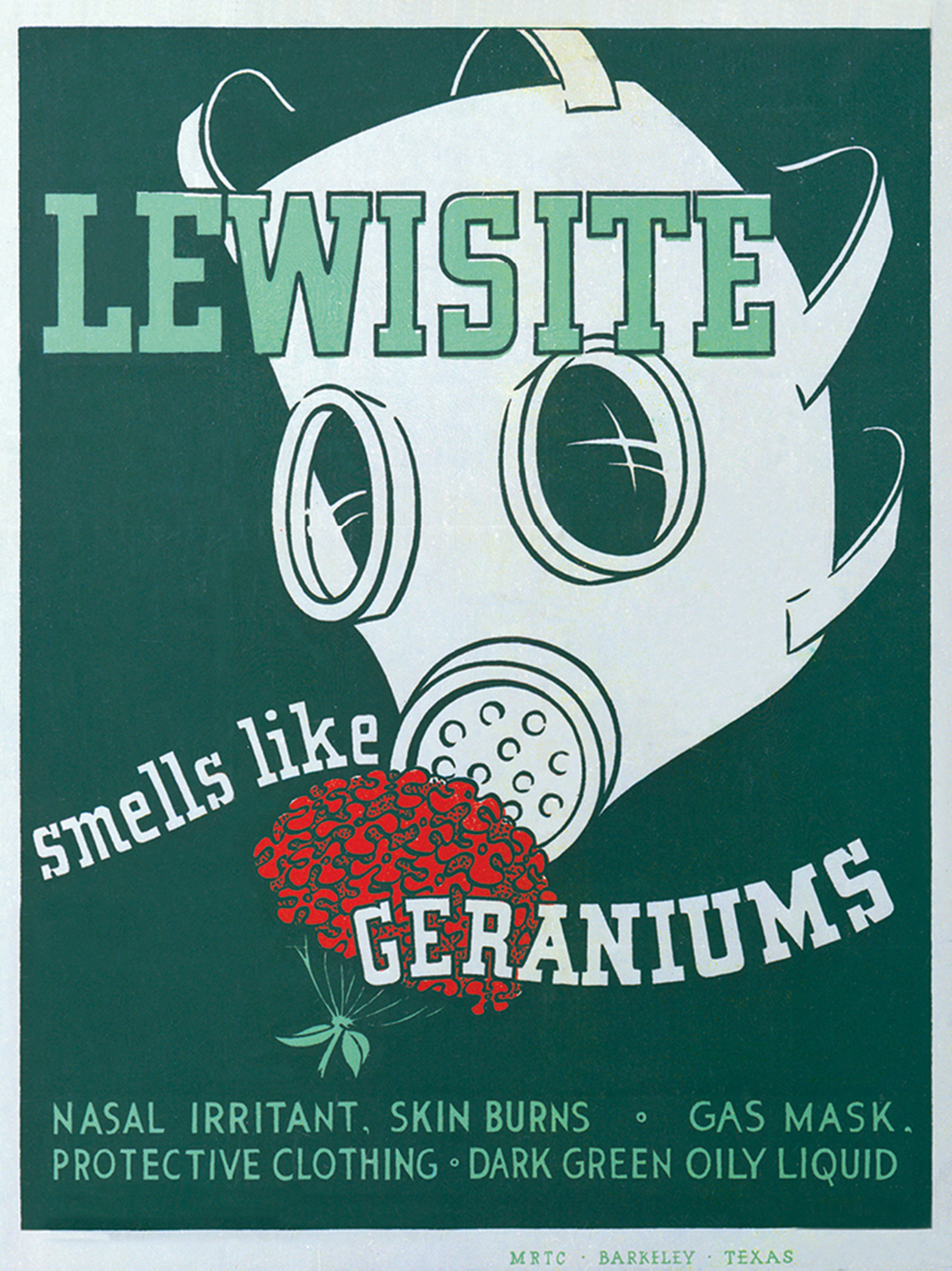

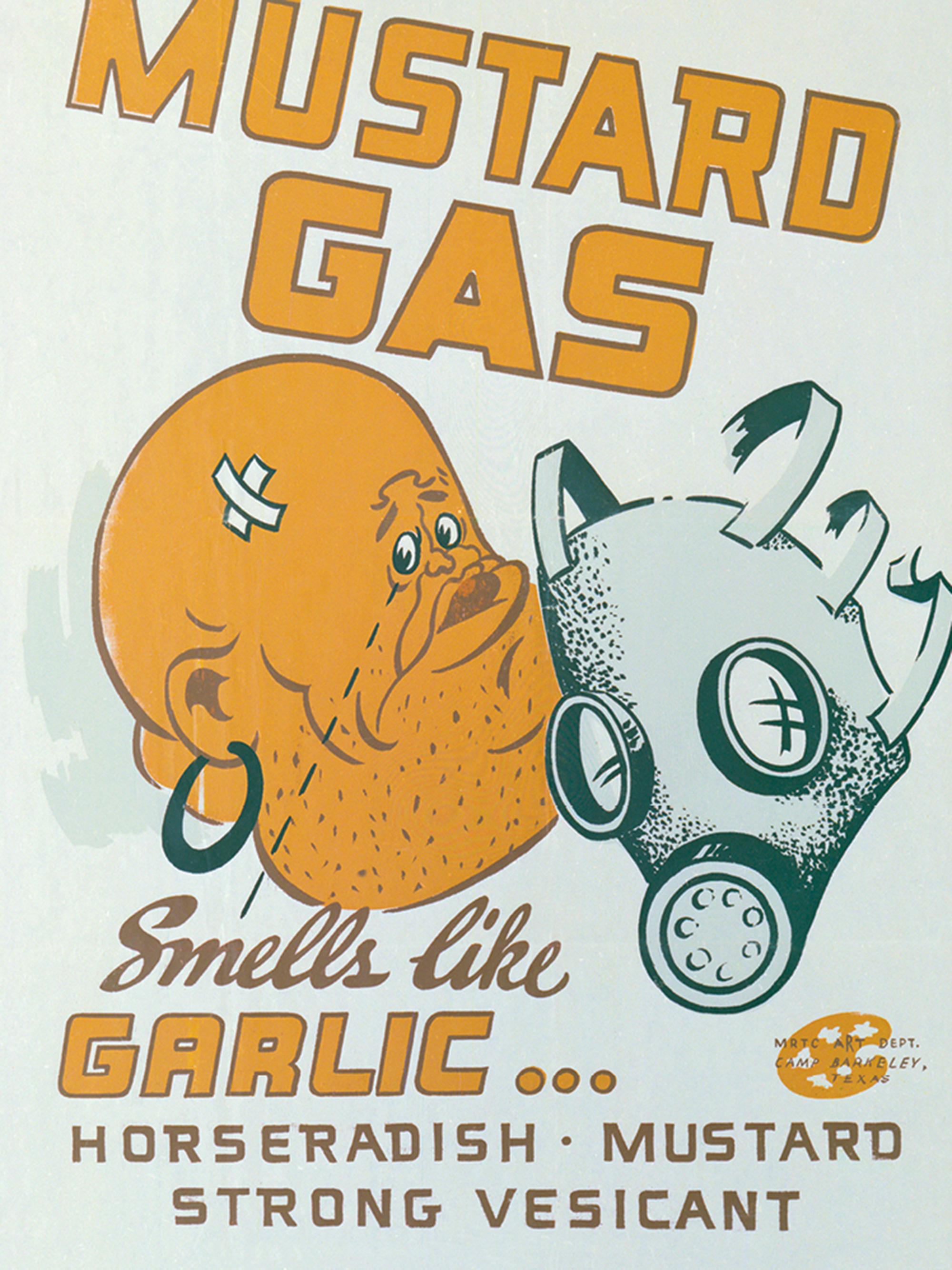

After all, it’s not only dogs who have to be trained. For $750, the Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear Defense Information Analysis Center will sell you a reinforced briefcase, full of red, blue, and yellow capsules, resembling an accessory from a high-priced board game. It’s designed to help emergency response personnel familiarize themselves with the smells of cyanide, lewisite, mustard gas, phosgene, sarin, soman, tear gas, ricin, botulinum, and something called “embryonated egg virus slurry.” In a sense, the Enhanced CBR Simulant Training Kit is a disaster movie or paperback techno-thriller adapted to a new medium: real dogs find real corpses all the time, but no one has ever released mustard gas on American soil, so the capsule containing its scent warns of a grim, low-probability hypothetical. (In World War II, the easiest way to train soldiers to recognize mustard gas was by describing the smell in words: “Smells like garlic, horseradish, mustard,” read one US Army poster.)

Some odors are so unpleasant that the problem is less recognizing them than enduring them. American soldiers arriving in Iraq were never likely to smell nerve gas because, it famously turned out, the only chemical weapons in the country were a few hundred rusty tins of useless sarin from the 1980s. But what they were certain to confront was a more banal miasma: burning rubber, diesel fumes, dead dogs, roasted goat, raw sewage, and all the other airborne excrescences of a Middle Eastern village in the aftermath of an invasion. The US Army operates several facilities for training its soldiers in MOUT, or military operations on urban terrain, some of them so elaborate that they resemble Disney theme parks. There, the technology of choice is Biopac Systems’ Scent Delivery System, which holds eight different scent cartridges and can be controlled via USB like a rock concert’s lighting rig. The Biopac system is most often used in stores, hotels, and resorts, and so most of the cartridges in the company’s extensive catalogue feature scents like Apple Pie, Buttered Popcorn, and Suntan Lotion. But there are also twenty-four “specialty scents,” which read like a list of keywords from a manly life well-lived: Barn Yard, Beer, Body Odor, Burning Electrical, Burning Leaves, Burning Rubber, Burnt Wire, Campfire, Cat Urine, Diesel Exhaust, Dirt Floor, Garbage, Grilling Meat, Hospital Smell, Human Feces, Lit Cigarettes, Low Tide, Manure, Marijuana Smoke, Mildew, Natural Gas, Race Car Exhaust, Swamp, Raw Sewage, Red Wine, Rum, Smelly Dog, Sulphur, Urine, Weapon Fire, and Whiskey. The only product in common between the two lists is Gunpowder, which presumably has cheerful associations for some people and less cheerful associations for others.

In high enough concentrations, some of these terrible fake smells could themselves constitute a kind of non-lethal chemical weapon. And that potential hasn’t gone unnoticed. Since 2009, the Israel Defense Forces has sprayed rioters and protestors with Skunk, a green liquid so foul that it apparently causes 90% of people to flee the area as soon as they smell it, often crying and vomiting. Skunk is an organic brew made with yeast and baking powder, and its inventor, Superintendent Ben Harosh, insists it’s so harmless you can drink it, but it’s also the case that a person’s clothes will retain the smell of Skunk for as long as two years. In this sense, it becomes a means of tagging miscreants, a bit like the exploding packs full of indelible dye that can stain a bank robber’s face bright red.

Skunk represents the first prominent use of an odor-based weapon since World War II, when the Office of Strategic Services developed Who Me?, an effluvial sulfur compound that the French Resistance hoped to use to humiliate German officers. Who Me? was not a success, but today the Pentagon’s Nonlethal Weapons Program continues to fund research at institutions like the Monell Chemical Senses Center, where in 2001 chemist Pam Dalton developed a substance called US Government Standard Bathroom Malodor, reportedly the worst smell in history. In the long run, innovation like this wafts out into the public realm mostly in the form of prank supplies: DSG Laboratories claim that the range of extreme stink bombs they sell through online retailers—including Hellstone and Brimfire, Liquid Roadkill, and Nasal Nausea—were originally manufactured under contract from the CIA.

Bad smells have always been a part of life and always will be. But the increasing use of simulated bad smells by various types of security forces seems to divide the whole world into fresh and rotten. Here, stench invariably connotes criminality and war, insurrection and terrorism, mayhem and foreignness. As Alain Corbin writes in The Foul and the Fragrant: Odor and the French Social Imagination, “Abhorrence of smells produces its own form of social power. Foul-smelling rubbish appears to threaten the social order, whereas the reassuring victory of the hygienic and the fragrant promises to buttress its stability.” Or, as George Orwell put it in The Road to Wigan Pier, “The real secret of class distinctions in the West ... is summed up in four frightful words ... the lower classes smell. ... You can have an affection for a murderer or a sodomite, but you cannot have an affection for a man whose breath stinks.” We might also be reminded of Newt Gingrich’s recent verdict on Occupy Wall Street: “Take a bath!”

And the entanglement of bad smells and authoritarian contempt has a firm psychological basis. One experiment at Cornell showed that an unpleasant whiff in the air caused people answering a questionnaire to report more negative attitudes towards gay men than a control group. “Apparently, the slightest signal that germs might be present is enough to shift political attitudes toward the right,” concluded the study’s authors. Viewed in these terms, Skunk—which Harosh hopes to license to security forces around the world—seems like a local and temporary means of concretizing the link by force: the poor might not reek yet, but if they cause any trouble, they certainly will soon. In the future, going a couple of weeks without a hot shower may not just be the unfortunate practical consequence of joining an urban protest camp—it may itself become a political act for engaged citizens in general. The aim will be to undermine the association between bad smell and bad citizenship, reminding our police, our soldiers, and even our dogs that good people can smell horrendous, and that truly evil things can happen in hotel lobbies smelling of nothing but sandalwood and cinnamon.

Ned Beauman is an author based in London. His novels are Boxer, Beetle (Sceptre, 2010) and The Teleportation Accident (Sceptre, 2012).

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.