Regarding the Pain of Others?

Snuff spectacle in the age of the scaffold

Dusty Keelson-Maar

Discipline and Punish, Michel Foucault’s important 1975 study of shifting penal regimes across the watershed of the late Enlightenment, opens with a harrowing account of the public execution of one Robert-François Damiens—a mentally unstable household servant who made a half-hearted and wholly unsuccessful attempt on the life Louis XV in early 1757. The king received a scratch.

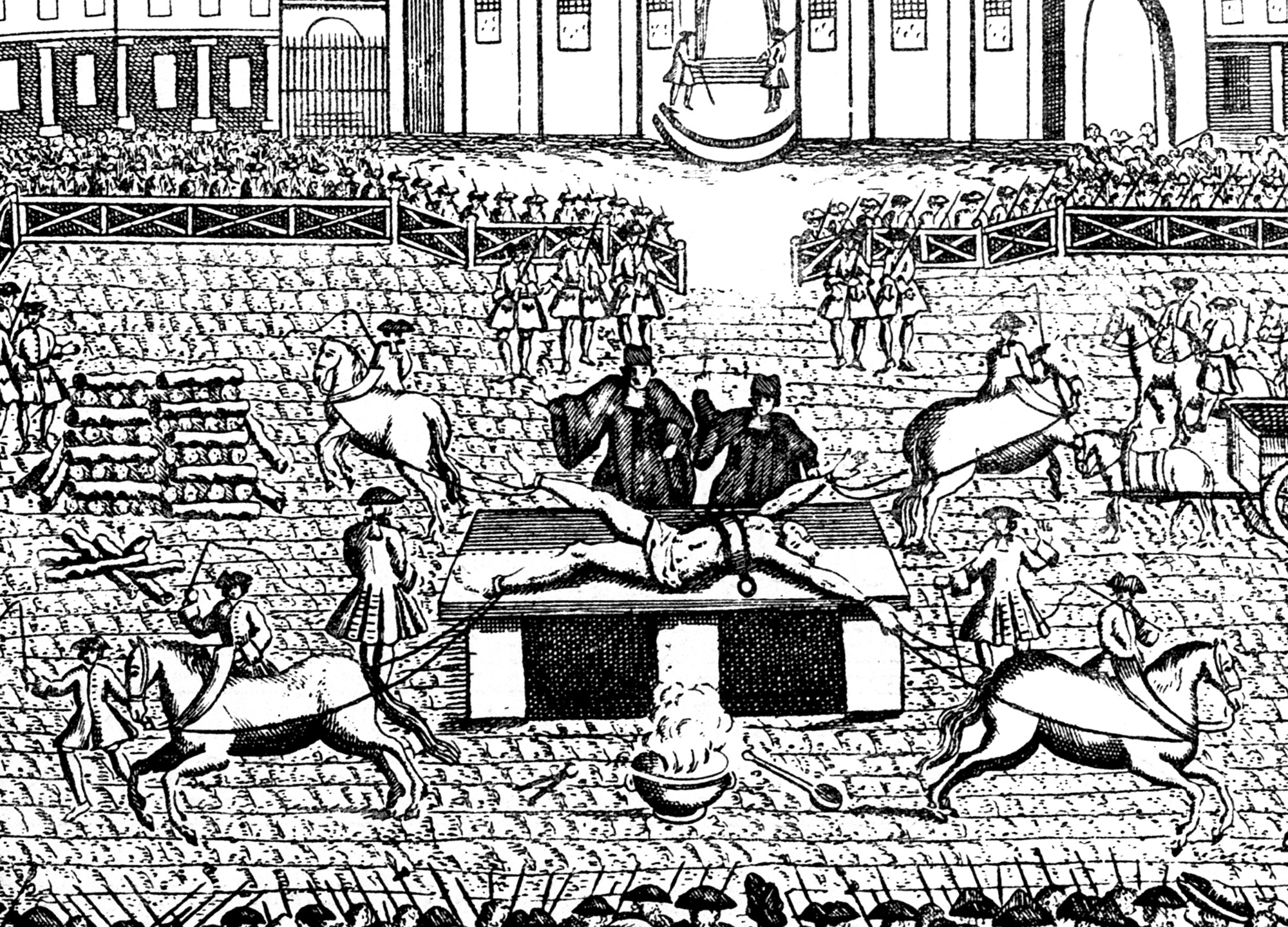

It was repaid with interest. Across the better part of a day, Damiens was subjected to a set of excruciations of extravagant cruelty: his offending hand slowly roasted in brimstone; gobbets of flesh torn from his breast, legs, and arms with purpose-forged steel pincers; the resulting wounds laved liberally with a concoction of molten lead and boiling oil. And all this was mere prelude to the main event, a quartering by horses (ultimately six, bound to his extremities), to be followed by the sequential reduction to ashes of Damiens’s resulting parts—with the torso to come last.

It turns out that the executioner had never attempted to quarter anyone, and it proved much harder than expected. After various unsuccessful permutations of horses and tackle (everyone pulling straight out at first, then rack-like, then legs in a split), resort was made to hackwork butchery. Eventually the remaining core of Damiens’s body found its way onto the pyre. Onlookers claimed still to see some life in the man who had now called plaintively for mercy for hours—his clenched jaw apparently continued to move, as if he would speak.

The first chapter of Discipline and Punish dwells exactingly on this gruesome procedure, since, for Foucault, Damiens’s theatrical destruction marks out in exemplary detail a veritable juridico-political cosmology—a world of penal belief and penal practice to be contrasted with the more familiar regimes that emerged over the subsequent century. Out went retaliatory spectacle predicated on an embodied, corporeal conception of sovereignty; in came sequestered regimes of carceral normalization. Out went the pincers; in came the penitentiary. Out went the glint and gaud of royal stagecraft; in came the insidious tendrils of administrative self-craft. The pornography of punitive violence gradually gave way to the intimacies of prison discipline—whether one was actually behind bars or not. Along the way, as Foucault would have it, something like the modern subject was born.

• • •

The pornography of punitive violence. This turns out to be more than a turn of phrase. Though Foucault cites several eyewitnesses to Damiens’s execution, he omits mention of perhaps the most notorious onlooker that day: Giacomo Casanova, the Chevalier de Seigalt. This Venice-born boulevardier—soldier, spy, musician, ambassador of intrigue from court to court and boudoir to boudoir—was then thirty, at the height of his powers (and the trough of his scruples). Never one to miss a party, the debonair Chevalier made arrangements to attend Damiens’s undoing in the company of a clutch of aristocratic Frenchwomen and a few devil-may-care hangers-on. The mix proved volatile—with Damiens’s shrieks serving as spark.

The following passage hails from volume five of Casanova’s 3,700-page memoir-monument, The History of My Life, the long labor of a roué’s gouty retirement. The principle actors are a robust Italian in his mid-twenties on the make (he would wind up as a mapmaker in Bengal) and an overweight Frenchwoman of about sixty, apparently toothless. Did Casanova invent the episode? There seems little reason to think so. Yes, here and there his yarns display tinselly embellishment. But mostly the twelve volumes of his masterwork afford unparalleled access to a lost world of libertinage, panache, and sadism both casual and studied. Which is this? Who can say for sure? What is certain is that Casanova’s momentary display of sympathetic sensitivity (his averted eyes could almost be said to instantiate Foucault’s epistemic shift in the culture of punishment) opens a disorienting, sidelong view onto the dark zone where penal and erotic regimes overlap—snuff-spectacle in the age of the scaffold.

While Damiens was being tortured I had to turn away my eyes when I heard him shriek with only half his body left; but La Lambertini and Madame XXX did not look away; and it was not because they were hard-hearted. They told me, and I had to pretend to believe them, that they could not feel the least pity for such a monster because they loved Louis XV so well. It is true, however, that Tiretta kept Madame XXX so strangely occupied during the whole execution that it may have been only on his account that she never dared to stir or look around. Being behind her [at the window] and very close to her, he had raised her dress so as not to step on it, and that was all very well. But later, looking toward them, I saw that he had raised it a little too high; whereupon, determining neither to interrupt my friend’s enterprise nor to embarrass Madame XXX, I took up a position behind my beloved which assured her aunt that what Tiretta did to her could be seen neither by myself nor by her niece...

Dusty Keelson-Maar is a Knox Fellow at the University of Cape Town. She specializes in French and Italian literature of the eighteenth century.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.