Who Better to Punish than the Innocent?

Capital punishment and human sacrifice

Justin E. H. Smith

In June 2011, US federal judge Larry A. Burns ruled that the schizophrenic, multiple-murder suspect Jared Lee Loughner could be forcibly medicated by prison doctors for his mental illness. This ruling, however, was made not in the interest of alleviating his distressing symptoms but rather in the interest of pursuing justice, or, as the prosecution would hope, pursuing Loughner’s eventual execution. Only sane people can be found guilty; only sane, guilty people can be executed; and it is only with the aid of antipsychotic drugs that Loughner might be considered sane.

How, now, did it come to this? Obviously, there was a time when raving demon-seers were the most likely to be punished. Possession, lunacy, folly, and feeble-mindedness all provided further incentive for penalization, rather than standing as impediments to it. Yet today we suppose that punishability has something to do with responsibility, which in turn is based on the counterfactual supposition that one could have done differently than one did. Being able to do one thing rather than another, as opposed to just going along with the flow of nature is, of course, something only free beings are capable of doing. And freedom, finally, is a condition of the brain, it is supposed, that can be lost with mental illness, and then restored with drugs.

Must one be sane to be guilty? And must one be guilty to be punished? Bernard Williams reminds us that for the Greeks it was enough to be tainted by miasma, which “was incurred just as much by unintentional as by intentional killing.”[1] The taint was simply the guilt that comes from bad luck rather than consciously wrong action. If this seems a harsh conception of justice, it is important to remember that, civic law aside, we have traditionally imagined that it is the only one that the cosmos respects or knows: they are punished who do the wrong thing at the wrong time, and the determination of wrongness is independent of malicious intention. Rather, a wrong action is one that sets the cosmos off-balance, such as incest in Oedipus Rex. It matters not at all whether the agent knows what he is getting himself into: these deeds are destabilizing, and the destabilized cosmos does not inquire after the state of knowledge of the actors who carried them out.

Williams considers some peculiar cases, including a certain poor soul in the Second Tetralogy, ascribed to Antiphon, who while practicing the javelin in the gymnasium was unfortunate enough to strike a runner in the distance. Is the javelin-thrower guilty? Whether he is or not, by Greek standards he is inexorably trapped in the miasma his unfortunate throw has produced.

Guilt without responsibility is not unique to antiquity, for neither was the connection between sanity, guilt, and punishment of much concern to the prosecutor in the 1499 murder trial against the pig owned by Jean Lelande. The pig had suffocated and devoured “a young girl named Gilon, of the age of one and a half years or thereabouts.” As a result, the jury ruled that “the said pig, for the reasons given and established in the said trial, is condemned to be hanged and executed by Justice.”[2]

Was there, then, a conception of porcine free will in late medieval France? Or are we catching a glimpse here of a forgotten penology? Lelande’s pig might be seen as a transitional figure: he is offered the trappings of civil law, but without any expectation that he in fact be the sort of being to which this law applies. The hanging is a punishment for a crime, but the beast is not really a criminal. In this respect, and whatever the human actors in the affair may have said about it, the fifteenth-century pig hanging calls to mind a far more ancient species of controlled violence: sacrifice.

As an initial stab, we may think of sacrifice as the ritualized killing of a creature, human or animal, for reasons having nothing to do with any real or perceived individual wrongdoing on the part of the creature. The killing is rather an offering to the gods or to rulers, who are themselves conceptualized as divine or as mediating between the divine and human spheres. A sacrifice is one whose victim is known to be innocent: in fact, this is the very quality that makes the victim suitable. Animals are good for this purpose, and so are virgins. Innocence here has both to do with the record of action and with the presumed inability of the victim to comprehend the reason for its death. It only comprehends, dimly, confusedly, that its end is desirable, perhaps even an honor.

Numerous ancient sources tell us that in many human sacrifices, the victims were also volunteers. We cannot be certain of what they were really thinking, of course, but it is hard to imagine that none of them were ever taken in, at least to a degree, by the reigning ideology, by the ambient chatter about what a worthy and desirable thing they were undertaking. Thus the tenth-century Arab traveler Ibn Fadlan writes in a chronicle of his expedition to the pagan Khaganate of Rus’ (later, Russia) that when a grandee died, one of his slave girls would volunteer to be dressed up in the finest cloths, have her throat slit, and then depart with her master down the river in a special cremation vessel.[3]

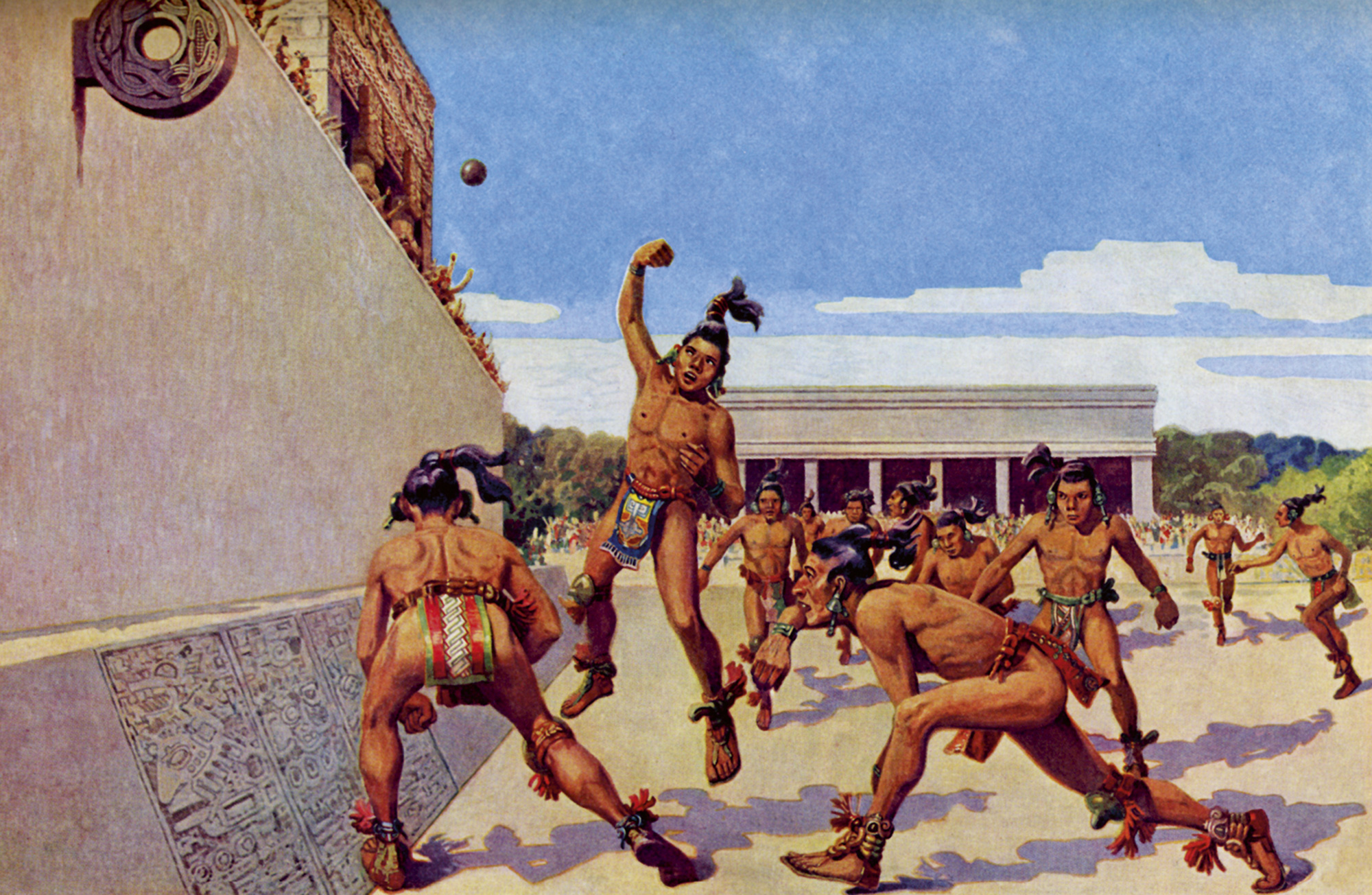

But let us move from the Volga to Mexico. There is tremendous variation, depending on region and century, in the rules and objectives of tlachtli, but we know for certain that some variants of the famous Mesoamerican ball game involved the sacrifice of the losing team. More surprisingly, in some subset of the games ending in sacrifice, the preceding match was not really a game at all, but a performance: the outcome was determined, the play choreographed.

We know from the Hellenic context that it is very common for sports to evolve from competitions to displays, and perhaps back again, and also for both of the possibilities to exist side by side (think, for example, of Olympic wrestling and Mexican lucha libre today, or of those sports that seem to perpetually straddle the boundary, such as synchronized swimming).[4] It has long seemed to me that sports would be far more interesting if the losing team were truly punished in the end. Of course, they are abstractly punished in that a record of losses will make for an unsuccessful athletic career, which will be poorly remunerated, and this might eventually result in real hardship. But there’s not much to watch in this, and it certainly cannot compare to, say, the delight in seeing Tim Tebow properly flogged.

But still, it would be a remarkable thing to consent to the punishment of one’s team, should it lose, knowing full well that it will lose. To do so only becomes at all comprehensible when we understand that the loss of the ball match might best be understood as a ritual enactment of what is to come. If it is not unheard of to see human sacrificial victims volunteering for the job, why should we be surprised to see them performing a ritual dance of loss beforehand, like El Hijo del Santo before he takes his fall?

There is no known case of an animal performing any such elaborate tricks prior to its sacrifice. But the lamb to the slaughter, in its passive acquiescence, is always believed to be, as they say, game: to be in on it and in agreement with it. How else do we explain its docility? One commonplace about hunter-gatherer belief systems, largely based in truth, is that they suppose that the hunted animal gives itself to the hunters; this, then, absolves the hunters and their dependents of guilt for an unpardonable transgression. One wonders whether they really believed this, but in any case we might suppose that there is a continuity between this assuaging thought and the belief in post-hunting, pastoral societies that the sacrificial animal, far from being a victim of injustice, is itself a restorer of justice.

What it was that the animals were consenting to was not a strictly human matter either, but also a cosmic one: that is, the social ritual was an enactment, confirmation, and support of the order of all of nature. Many accounts of animal sacrifice in ancient texts describe the cosmos itself as emanating, in fact, from what a butcher today would call the “cuts” of the slaughtered animal. Thus in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad:

The head of the sacrificial horse is verily the dawn; the eye of the horse is the sun; the vital force, the air; the open mouth, the fire named vaisvanara; the trunk, the year; the back, Heaven; the belly, the sky; the hoof, the earth.[5]

The ashvamedha ritual is thus a sort of cosmogonical reenactment, and through its symbolic recreation of the cosmos, it preserves the cosmos. In the Upanishadic horse, there is in fact the echo of a similar mythical sacrifice in the Rig Veda, of a millennium or so earlier, in which the world and all its stars and planets and waters, and the horses themselves, spill out from the sacrifice of Purusha, the primordial man:

They balmed as victim on the grass Purusha born in earliest time. ... From that great general sacrifice the dripping fat was gathered up. He formed the creatures of the air, and animals both wild and tame. From that great general sacrifice ... were horses born, from it all cattle with two rows of teeth: From it were generated kine, from it the goats and sheep were born.[6]

Animal sacrifice can thus not be completely separated conceptually from human sacrifice. The latter provides a limit-case of what sacrifice ultimately does, namely to restore the balance between the political and the cosmic orders through the mediation of a living body.

Now given this weighty function, the person who officiates it obviously is someone with a great deal of power. This is, moreover, a power not just to kill, but also to spare. A pardon, in fact, may be seen as a sort of inverted sacrifice, as vividly evidenced in the annual presidential turkey pardon at Thanksgiving in the US. As Magnus Fiskesjö compellingly argues, the sparing of a token bird’s life is a classic “first-fruits sacrifice,” in which “the symbolic gesture of refraining from consumption of a token sample opens the way for mass consumption of that same desired good.” The symbolic gesture gets the gods involved: only they could have the real power—Christians call it “grace”—to miraculously save this creature, this one creature which nothing in the realm of reason really recommends for special treatment. And it is the president who performs the ritual for the gods. His act of pardoning, Fiskesjö thinks, “effectively recreates and reaffirms the people as members of their tribe, and the chief as their chief, charged with channelling divine forces.”[7]

The turkey pardon is a paradigm case of the very serious joke. Obama has evidently been rather embarrassed by it; George W. Bush seems to have thought it was all what he himself might call “a hoot.” It reveals, in a way that only a joke could, something profound about American political culture: that it takes itself to be woven into the order of the cosmos, that its legitimacy is derived from on high. In this respect, the jocular turkey pardon cannot be considered separately from other assertions of US political power over life and death. As Fiskesjö puts it, the joke is itself the justification of this power. We might also add that it is the ritual restoration of this power, just as the Vedic horse sacrifice once echoed and recreated the original cosmogony.

Every joke requires a context, and it is safe to suppose that this one would not be successful if, say, the prime minister of Sweden were to attempt to reproduce it. Fredrik Reinfeldt does not project enough real power to enable such an exercise of parodic power to make sense. Among other things, no Swedish politician has the power to spare the life of a condemned prisoner. There is no death penalty in Sweden.

It should not be hard to see, now, that the serious non-joke that makes the serious joke work is capital punishment. For a government to carry out the death penalty with an air of legitimacy: what a coup de grâce for political theology! And this in the strong sense: not that government takes over some of the trappings of religion, but that the power of the state over life and death derives from a direct embedding of the political order within the transcendent one, just as for the brahmins the reason that pervades and orders the cosmos (the rta) was reflected in the organization of the castes, and in turn in the conformation of the body, human or equine.

The society that continues to resort to the death penalty remains a sacrificial society. But wait, you might insist: Isn’t there a key difference in that sacrificial victims are chosen precisely for their innocence, while criminals are condemned for their guilt? And isn’t guilt a non-transferable and objective state of an individual, resulting from his having taken one course of action when he could have taken another? Isn’t this precisely what is holding up Loughner’s execution?

Capital punishment, as a remnant of sacrificial culture, is fundamentally at odds with the basic penology and jurisprudence that dictate how prisoners must be treated, and it is from this incompatibility that so many prima facie absurd practices arise, such as the effort to medicate Loughner into sanity in order then to punish him. Another absurdity is the constant migration from one method of execution to another on the grounds of the new method’s greater “humanity.” No method can ever be found that will give the self-styled humanists what they really want: capital punishment without corporal punishment, a taking away of life that does not have to work through the body.

If the concern for sanity, responsibility, and humanity were stripped away, we would see the enactment of the death penalty for what it is: human sacrifice, and so also a regeneration of the social order, preserving the cosmos in its delicate balance.

- Bernard Williams, Shame and Necessity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), p. 59.

- See E. P. Evans, The Criminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals (New York: E. P. Dutton and Company, 1906), Appendix N, p. 352.

- See Ahmed Ibn Fadlan, Ibn Fadlan’s Journey to Russia: A Tenth-Century Traveler from Baghdad to the Volga River, ed. and trans. Richard Frye (Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers, 2005).

- See Mark Golden, Sport and Society in Ancient Greece (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

- The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad (Madras: Sri Ramakrishna Math, 1951), p. 2.

- The Rig Veda, trans. Wendy Doniger O’Flaherty (New York: Penguin, 1981), pp. 160–162.

- Magnus Fiskesjö, “The Reluctant Sovereign: New Adventures of the US Presidential Thanksgiving Turkey,” Anthropology Today, vol. 26, no. 5 (October 2010), pp. 13–17.

Justin E. H. Smith is professor of philosophy at Concordia University in Montreal. He is the author of the forthcoming Nature, Human Nature, and Human Difference: Early Modern Philosophy and the Invention of Race (Princeton University Press).

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.