Two by Two

A timeline of twins

William Viney

Twins have cut a naturally anomalous figure in the field of human understanding. Though we expect to meet twins and some of us even end up expecting twins, the meanings attached to them vary greatly across time and space. Whether they’re monozygotic, dizygotic, or conjoined twins, people who have been born together have been attributed with qualities of startling similitude, divine communion, demonic mediation, anarchic monstrosity, and scientific promise. A history of twins, then, must also include the parallel tale of these exceptional gifts, whether real or imagined—this panoply of extreme fears, common superstitions, and strange delights.

As cross-cultural figures in mythological thinking and now unique participants in the scientific classification of our bodies and behaviors, twins and the idea of twinning litter the history of human self-regard. Twins, neither one nor simply two, enjoy a semantic mobility that has absorbed them into countless debates regarding the tractability of human nature. These dubiously double figures and the precise nature of their relation—whether physical, behavioral, linguistic, or mathematical—has forced twins into these debates as convenient object lessons. But their anomalous natures mean that they are also structuring forces in these debates, proscribing the horizons of possibility. Writing the history of twins is therefore to write against the grain of a history dominated by the acts of great individuals.

N.D.

Every culture bears twins and almost every culture entertains myths about twins. Greek myth is particularly twinly—from the day and night of Apollo and Artemis to the “twincest” of Byblis and Caunus to the killing of the monstrously conjoined Eurytos and Cteatos by another twin, Hercules. Mythological twins are often born through the union of god and mortal, redistributing the sacred and profane, the human and the animal. Both in the Greek tradition and globally, where foundational twin myths can be found in extraordinary number, twins frequently gain the favor of gods or are considered gods in their own right.

1836 BC

In cultures of primogeniture, multiple births can lead to violence and dispute between twin siblings. In the Judaic tradition, a dispute between twins founds a nation. Rebekah is told, “Two nations are in thy womb, and two manner of people shall be separated from thy bowels; and the one people shall be stronger than the other people; and the elder shall serve the younger” (Gen 25: 22–23).[1] Jacob and Esau’s birthright, or bekhorah, is a central source of their dispute and, after trading, deceiving, and dodging, Jacob receives the favor of Isaac and YHWH. His name is changed to Israel by an angel and the struggle for Jewish nationhood is forever tied to these quarrelling two.

771 BC

On the morning of the foundation of Rome, there are two twins, two factions, two hills, and two flights of vultures. At the involuted point of this foundation rests the death of Remus, an original wrong for a city that will, much later, attempt to church the world. Supposedly discarded on the banks of the Tiber and suckled by a wolf, Romulus and Remus are protagonists in a warring story the proper interpretation of which remains contested: modern scholars now dispute whether Romulus had a twin at all.[2]

161

The average size of a Roman family was small and multiple births drove financial as well as religious anxieties. While multiple births of more than two were cause for anxiety, twin births were often viewed as a fortuitous blessing and a sign of fertility. When Faustina the Younger, wife of Marcus Aurelius, gave birth to two sets of twins, coins were issued in celebration bearing the inscription SAECVLI FELICI, “the fortune of the age.”

287

The twin Turkish physicians, Saints Cosmas and Damian, are martyred during widespread persecution of Christians by Emperor Diocletian in Syria. Stones, arrows, and the rack prove miraculously ineffective; beheading is their final fate. While alive, they are said to have healed the sick without charge; in one particularly miraculous episode, they are said to have replaced the missing leg of a Roman deacon with that of a recently deceased Ethiopian. They are now the patron saints of doctors, nurses, surgeons, pharmacists, dentists, and barbers.

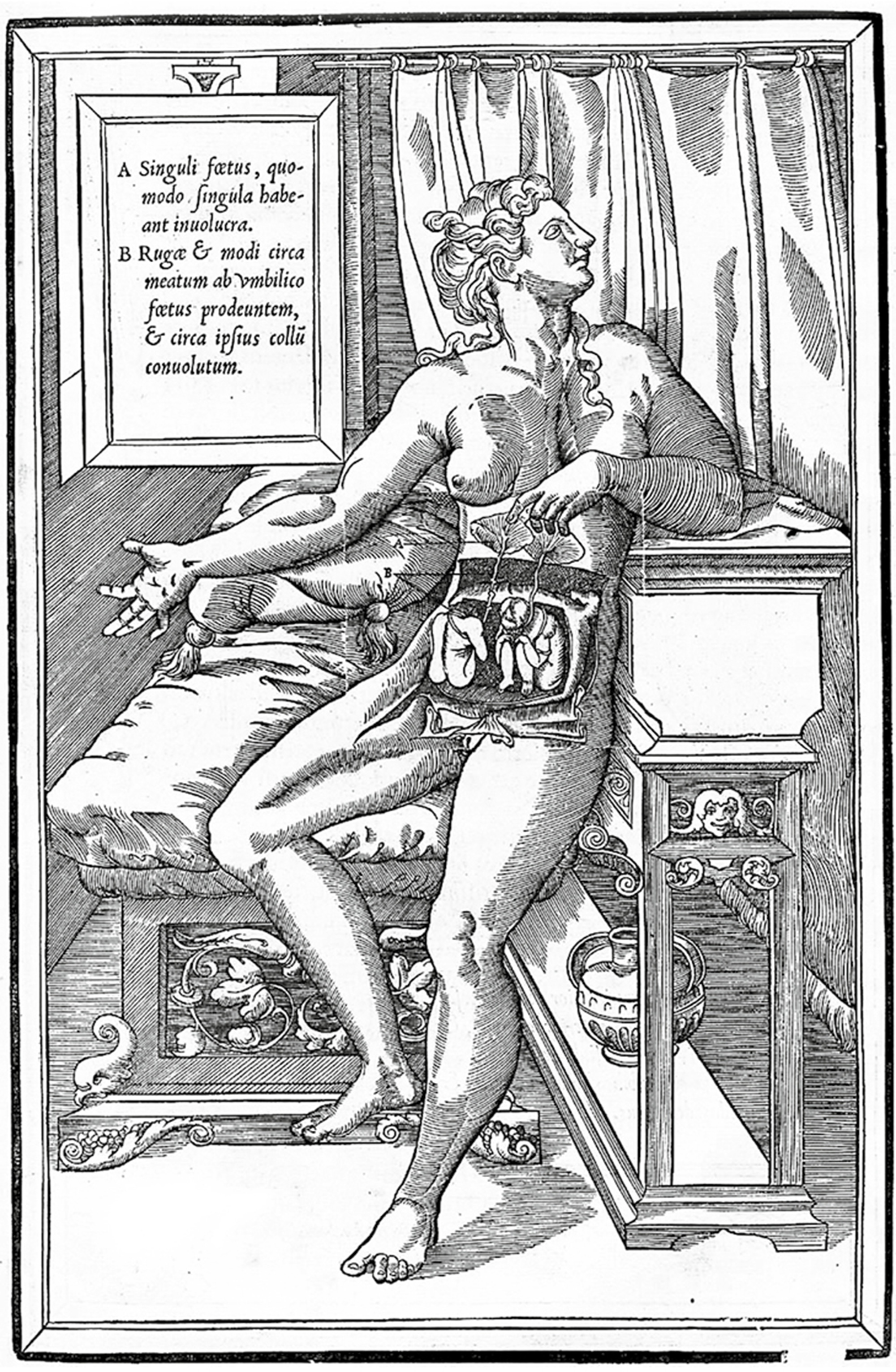

1545

Unfairly derided as a plagiarist of Andreas Vesalius, the lesser-known, Parisian anatomist Charles Estienne attempted to visualize, perhaps for the first time, the condition of twins in the womb. In the “self-dissecting” style popular at the time, his De dissectione partium corporis humani shows twins huddling beside one another in their mother’s womb. With umbilical cords wrapped tightly around the necks of each child, Estienne shows an interest in the crowded, competitive, and precarious nature of a twin’s uterine environment.

1596

Hamnet Shakespeare, twin of Judith and only son of William, dies at the age of eleven. Other poets of the period coped with the death of a child through elegy. But the literary traces of Hamnet’s death in Shakespeare’s work are as much a mystery as its cause. Although the playwright’s interest in estranged twins is clear from around 1594, with the knockabout farce of The Comedy of Errors in which two sets of twins are reunited, the theme recurs in Twelfth Night (1601) with Viola who goes in search of her brother Sebastian who she fears is dead. What’s in a name? It’s hard to say. The passing of Hamnet in 1596 provides further enigma to the tragedy of the brooding Danish prince written soon thereafter.

1617

Lazarus and Joannes Baptista Colloredo, early modern Europe’s favorite conjoined twins, travelled throughout Italy, Germany, Denmark, Scotland, and England. Joannes Baptista, whose body consisted of a torso and head hanging limply from his brother’s stomach, would respond when touched but did not speak. To avoid the inconvenience of permanent performance, Lazarus would cover his brother with his cloak.

1689

Swiss pediatric surgeon Johannes Fatio performs the first successful separation of conjoined twins, Elizabeth and Catherine Meyerin. Fatio severed a xiphopagus join (a join of the sternum) by passing a tight ligature around the joining band and then cutting it.

1828

When Robert Hunter and Abel Coffin persuaded King Rama III of Siam to allow Chang and Eng Bunker to go on tour, these “Siamese twins” could only have guessed at the scale of celebrity that awaited them. They exhibited themselves for four decades throughout America and Europe, married sisters in 1843, and fathered twenty-one children (the eleven that survived were both half-siblings and first cousins). Attached at the sternum by a small piece of cartilage, their livers were joined but functioned separately. Chang’s alcoholism was a source of considerable disharmony. In a short text about the pair, Mark Twin observed, “When one is sick, the other is sick; when one feels pain, the other feels it; when one is angered, the other’s temper takes fire.” Not entirely true. On a trip back from Russia in 1870, Chang became paralyzed from a stroke. Eng supported him for three years until they died on 17 January 1874, two-and-a-half hours apart.

1875

Darwin’s cousin Sir Francis Galton coined the expression “nature and nurture” in relation to his twin studies. Galton felt that twins shared time “like two watches, hardly to be thrown out of accord except by some physical jar.”[3] His conclusions are now discredited for their inattention to environmental influence as well as their social and racial prejudice. But the belief that twins can “weigh in just scales the effects of Nature and Nurture” has had a lasting impact on behavioral genetics.

1932

Anxious that a future dominated by the principles of Galtonian genetics might seek to engineer twins in a Fordist manner, the novelist Aldous Huxley populated his dystopian future with “an interminable stream of identical eight-year-old male twins” to create a “nightmare of swarming indistinguishable sameness.” It is this revulsion at the sight of twins that names the novel, “‘How many goodly creatures are there here!’ The singing words mocked him derisively. ‘How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world …’”[4] Largely due to assisted reproductive technologies and ovulation stimulation therapies, twin births in the US rose 76% between 1980 and 2009.

1943

On arrival at Auschwitz-Birkenau, new prisoners would encounter a wild-eyed man on the platform shouting “Zwillinge heraus! Zwillinge heraustreten!” (Twins out! Twins step forward!). Jewish and Romany twins were separated from their families and after every part of their bodies had been measured, were subjected to agonizing and bizarre experiments; after death, they were dissected in order to examine racial characteristics. Joseph Mengele, known as the Angel of Death, was responsible for the murder of over a thousand twins between 1942 and 1945.

1954

The world’s first successful kidney transplant between a live donor and recipient took place in Boston when Richard Herrick, who was dying from chronic nephritis, an inflammation of the kidneys, received a kidney from his identical twin, Ronald. Richard died eight years after the operation and would have lived longer had doctors successfully removed all the infected tissue from his body.

1976

By the age of six, twins Grace and Virginia Kennedy, or Poto and Cabengo as they called themselves, still spoke no English. They were diagnosed as having developed an acute form of cryptophasia, or secret language. Baffling to medical professionals and incomprehensible to their worried parents, they became something of a television sensation; journalists marveled at these young savants capable of creating a “new” language. In fact, it seems that they were just pronouncing the English and German words spoken at home very badly. For instance, rather than saying, “Dear Cabengo, eat,” Grace once said, “Liba Cabingoat, it.” They spoke quickly and altered their pronunciations enough to make their conversation difficult to follow; they are reported to have had at least sixteen different ways to say “potato salad.” They were later forbidden from speaking anything other than English and were sent to mainstream schools, and eventually retreated from public life.

1979

Jim Lewis decides to try and find his twin brother, from whom he was separated at birth. Six weeks later, he knocks on the door of Jim Springer in Dayton, Ohio, and discovers he has been leading a parallel life. The “Jim Twins,” as they became known, both suffered from heart problems; had migraines from the age of eighteen and stopped having them at the same age; were compulsive nail-biters; and suffered from insomnia. Both had married women named Linda, divorced, and then married women named Betty. One had named his son James Alan and the other James Allen; both called their dogs Toy; both had worked as deputy sheriffs, gas station attendants, and at McDonalds. They both vacationed on the same Florida beach, smoked the same brand of cigarette, and drank the same brand of beer.

1999

A twenty-one-year-old woman is raped in a Michigan parking lot. The victim is unable to identify her attacker and no fingerprints are found at the crime scene. DNA evidence identifies Jerome Cooper, who had in the meantime been jailed for an unrelated crime. Detective Les Smith of the Grand Rapids Police Department speaks of his relief at solving the case, only to have it cut short by the discovery that Jerome has a twin brother, Tyrone. Both twins have criminal records for assault and both are without an alibi for the night of the rape. While physically dissimilar (Jerome is slimmer and shorter than his brother) current technology cannot distinguish between sperm samples of monozygotic twins. DNA evidence is usually enough to force convictions but here it was unable to provide positive identification. This case, as well as many others like it, remains unsolved.

- The date stated here for the birth of the twins is of dubious merit. 1836 BC is the date given by James Ussher, the Archbishop of Armagh, who, in his influential work Annales Veteris Testamenti (1650), argued that the earth was created on Sunday, October 23, 4004 BC.

- T. P. Wiseman, Remus: A Roman Myth (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995).

- Francis Galton, “The History of Twins as a Criterion of the Relative Powers of Nature and Nurture,” Fraser’s Magazine, no. 92 (1875), p. 574.

- Aldous Huxley, Brave New World (London: Vintage, 2007), pp. 183–184.

William Viney is a postdoctoral research fellow in the Centre for Medical Humanities, University of Durham, UK. His first book, Waste: A Philosophy of Things, will be published by I. B. Tauris in 2013.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.