Ingestion / Diplomatic Service

The ceremony of the state dinner

Paul Freedman

“Ingestion” is a column that explores food within a framework informed by aesthetics, history, and philosophy.

Just as friendship and courtship are enhanced over a sociable meal, diplomacy has often been advanced by ceremonial dining. These formal state dinners may not seem ideal occasions for casual interaction, but historically they have provided national leaders with the opportunity to sit together in the friendly environment that surrounds festive commensality. When kings and aristocrats dominated Europe, state dinners were gorgeous and elaborate affairs whose excesses and exotic effects accompanied the sealing of alliances. In December 1458, for example, the Count of Foix, representing the king of France, presented diplomatic emissaries of the king of Hungary with a seven-course dinner. It included a single course of fifteen kinds of game (including swans and peacocks), followed by more roast game birds presented as if “riding” on glazed suckling pigs and “armed” with lances and shields. The last course consisted of hippocras (spiced wine) accompanied by sugar confectionaries in the shape of various animals bearing the shields of the king of Hungary and the nobles present at the event. A banquet hosted by Duke Phillip of Burgundy in February 1454 was intended to rally support for a crusade to free Constantinople, recently fallen to the Turks. An immense pie held musicians who played as the crust was opened, and a second confection in the form of a church was discovered to contain within it a choir; there were also representations of classical myths and allegorical tableaux of the distress of Christendom at this extraordinary event. Known to posterity as the “Feast of the Pheasant” for its main course, the dinner also served as an occasion for the knights in attendance to swear an oath on the bird to aid the crusade.

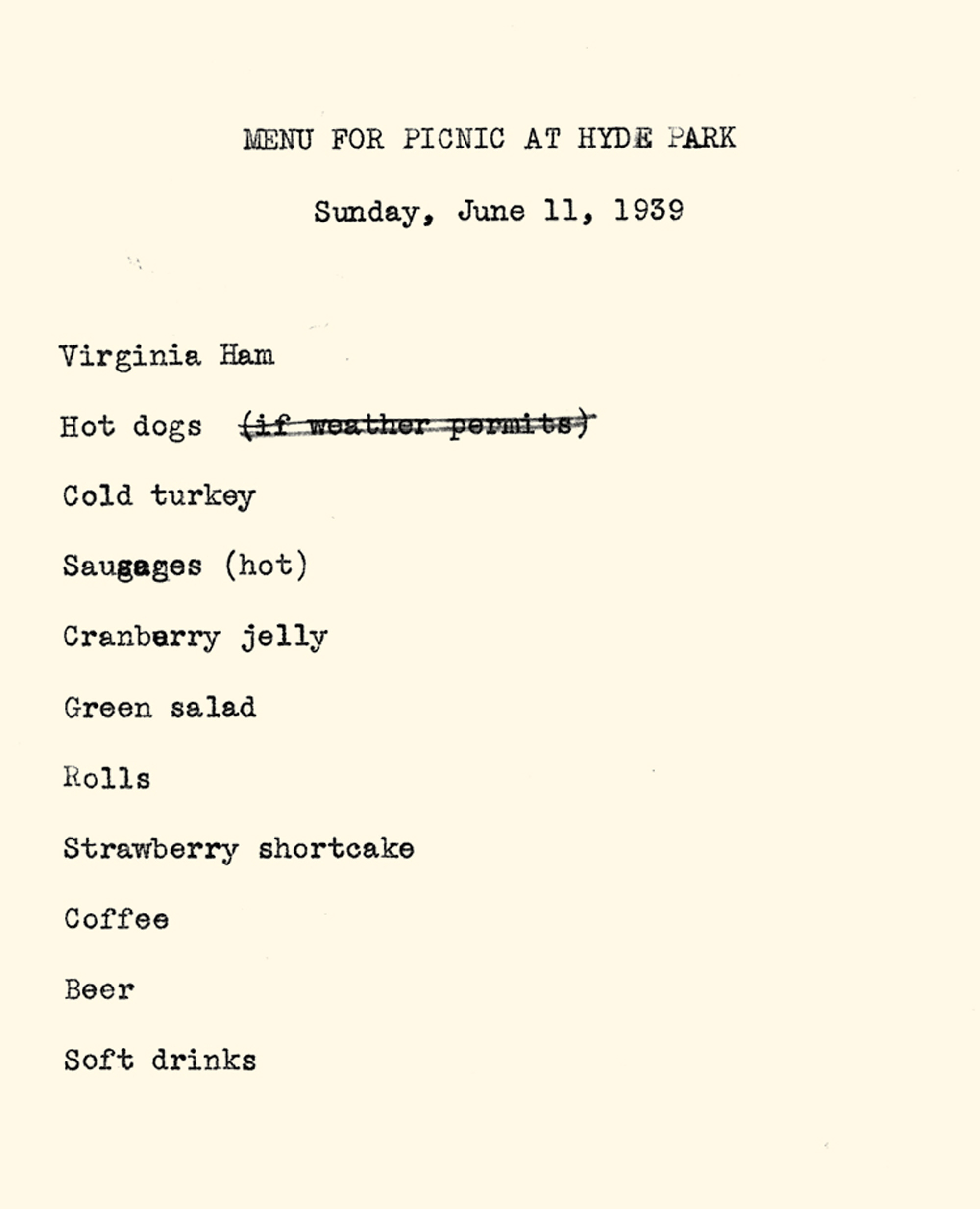

Modern state dinners are disappointingly low-key by comparison. Indeed, some have become famous because of their very informality. The 1939 visit of King George VI of the United Kingdom to President Roosevelt’s private estate in Hyde Park, New York, for example, featured hotdogs, a daring gesture that was celebrated by journalists and even memorialized by a calypso song with the chorus “Hot dog, hot doggie, oh what a dog” (“Hot Dogs Made Their Own Name” by Wilmoth Houdini).

The past century has seen dramatic summit meetings and other memorable political encounters, but who remembers the food served at Yalta in 1945 or at Reagan’s meeting with Gorbachev in Iceland in 1986? The most famous exception, and the most consequential political banquet of modern times, is the first dinner that took place during Nixon’s visit to China in 1972. The sight of the president and Mrs. Nixon deftly and nonchalantly using chopsticks awed the American public. Nixon was otherwise not much of a gastronomic adventurer, at least not in directions normally recognized as tasteful. His favorite thing to eat was cottage cheese with pineapple chunks and ketchup. Nevertheless, in Beijing he seemed to be unfazed by the splendid but unfamiliar array of dishes. The dramatic diplomatic breakthrough represented by the friendly encounter between Nixon and his hosts was both reinforced and symbolized by the American delegation’s apparent enjoyment of such Chinese classics as thousand-year-old eggs, shark-fin soup, and plum blossom dumplings. Not only did the presidential trip alter the geopolitical balance of power, it stimulated a new American enthusiasm for Chinese cuisine. Restaurants vied to serve the Beijing banquet menus and, at the same time, started to expand beyond Cantonese food to include the cuisines of provinces such as Sichuan and Hunan.