Making Up Hollywood

Max Factor and the invention of modern cosmetics

Sasha Archibald

Cinema tends to make beautiful people look more beautiful, but it wasn’t always so. In its earliest days, film had an adversarial relationship to beauty, exaggerating the tonal and textural variations of the human face so that even the most stunning heroine became a blotchy caricature. Early black-and-white film stocks—first, orthochromatic film, dominant until 1927, and to a lesser degree its successor, panchromatic film—rendered dark colors darker and light colors lighter, turning features that seemed innocuous off camera (rouged cheeks, a constellation of moles) into distracting blemishes when seen on the screen. Pimples and freckles looked like spots of mud and blue eyes seemed colorless; lipstick made the mouth a cavernous hole and a complexion with sallow or pink undertones appeared, in the term of the time, “negroid.” Techniques borrowed from the stage also proved problematic: face paint used to suggest wrinkles to a theater audience, for example, read as tattoos on film. Cinematic makeup, then, was not born from vanity—it was a necessary antidote to the flawed medium of film.

At first, film actors would arrive on set already made up, having used either a commercial greasepaint product designed for the stage or homemade concoctions of lard, talc, and pigment. Actors shared tips with each other and a few studios provided how-to pamphlets. A more convincing skin color could be made by adding brick dust or paprika; a layer of cold cream, petroleum jelly, or vegetable shortening could be applied before the paint, and a puff of flour after, to diminish the shine; white paint could be used to hide a double chin; dimples could be drawn in with a touch of lipstick. But even with the most expert application, greasepaint was a crude medium. It was stiff and dense, and tended to aggravate skin conditions that then required more greasepaint. There was no solution for the seams that were visible along the hairline and collar, and, as the name suggests, the substance was nearly impossible to wash off. Most vexing of all, greasepaint remained perfectly intact only when the face was slack. A lifted eyebrow or a smile caused the makeup to craze with hairline cracks. Though imperceptible to a distant theater audience, the defect was catastrophic on film.

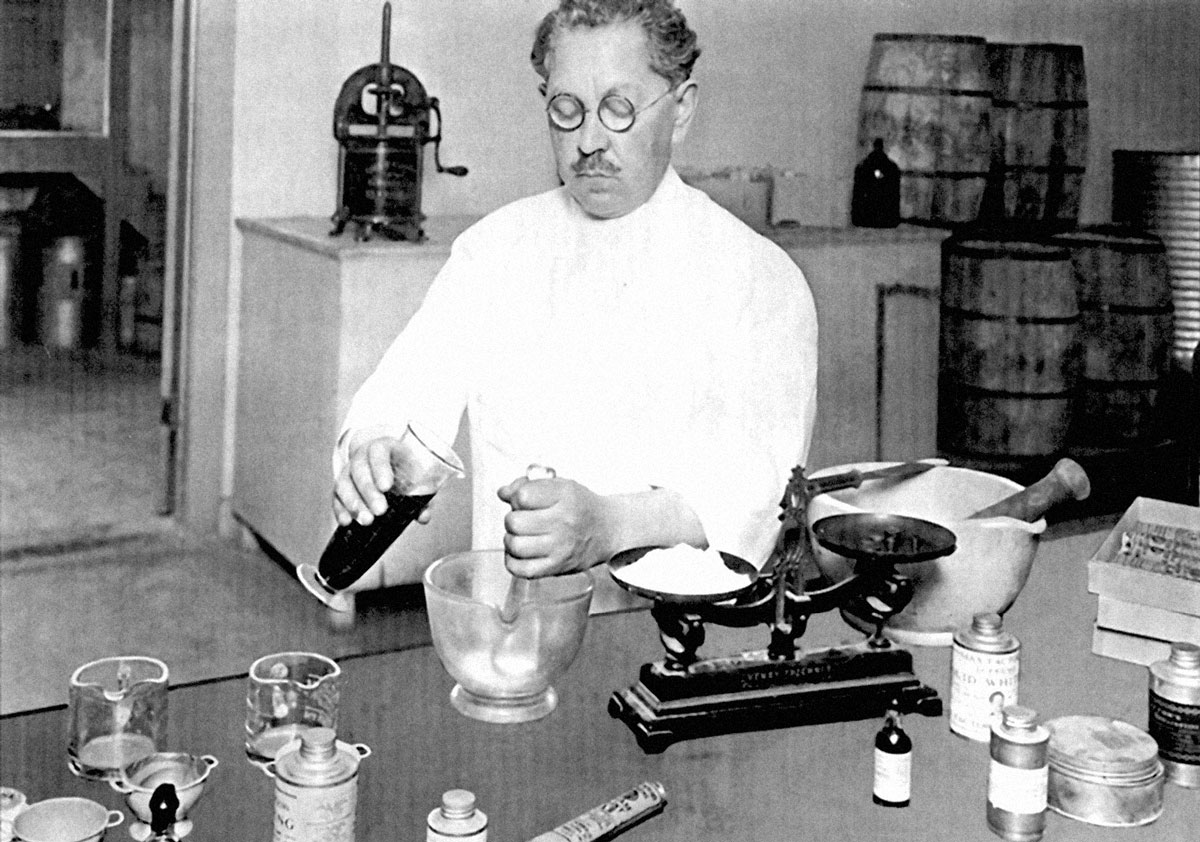

Silent-film comedians were the first fans of a new “flexible” greasepaint introduced in 1914 by a small wig and cosmetic shop in Los Angeles. “Flexible Grease Paint” had a very different feel to it, and customers requested that the proprietor demonstrate how to apply it. The store soon developed a steady clientele of actors who were happy to pay someone else to do their makeup. Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and the cross-eyed Ben Turpin needed to be on set by seven in the morning; The House of Make-Up began opening at five thirty.

The shop owner was Max Factor, a Jewish Polish immigrant whose surname—Faktorowicz—had been truncated and misspelled at Ellis Island. Factor never learned to speak English fluently or to drive a car, but his business acumen, innovative formulas, and sense of style were unrivaled in Hollywood for over two decades. Factor excelled at both the tangibles and intangibles of beauty culture. He invented a handful of products now commonplace—the eyebrow pencil, lip gloss, concealer—and improved on dozens of others, but his special talent was in using hair and makeup to project a specific sensibility or temperament. Tasked with creating innocence in a starlet, worldliness in a hero, or smoldering sensuality in a leading lady, Factor marshaled the humble repertoire of a beautician to give form to such abstractions.

Born in 1877 in Lodz, Factor, one of ten children, was apprenticed to a local apothecary when he was eight. By the age of nine, he was training with the city’s leading wigmaker and cosmetician, and shortly thereafter began traveling with the Imperial Russian Grand Opera. Following his obligatory military service, Factor opened his own shop south of Moscow, in Ryazan. After servicing a theatrical troupe that performed at the royal palace, he was summoned to serve as personal cosmetician to members of the czar’s court, including his physician. He was generously compensated and surrounded by opulence, but forbidden from leaving the palace except for an escorted trip each week to his shop where he collected supplies. During one of these visits, he met a young customer, and in the following years secretly courted and married her, and even fathered three children with her, all completely unbeknownst to his royal escorts. As his children grew older, however, the situation became increasingly untenable, and the couple eventually devised a plan of escape. In early 1904, Factor used his own formulas to affect a sickly pallor. When allowed to visit a sanatorium, he arranged for his wife and children to join him and, under cover of night, they escaped on board a steamer bound for America.

His first years in the US were cursed with setbacks. During the passage, he had been told of the St. Louis World’s Fair and headed there immediately to sell his face creams and hairpieces; business was good but his partner, a young man he had met on the ship, took off with the profits. A few years later, Factor’s wife died suddenly of a brain hemorrhage, leaving Factor a widower with four young children. He remarried immediately, but his new wife suffered a breakdown after the birth of their child; when she began hitting him in front of customers, he filed for divorce. Then his half brother arrived from Poland—Factor offered him training and employment, only to be betrayed when his sibling opened a shop a block away. (He later became a gangster.) Hoping for a fresh start, Factor remarried again and, by 1909, had taken his third wife and five children west to Hollywood. His arrival couldn’t have been more propitious.

Hollywood was on the cusp of consolidating its power as the movie capital of the world and, beginning with his Flexible Grease Paint, Factor became an integral part of the vast network of auxiliary enterprises that supplied the film industry. Factor’s business had a symbiotic relationship with Hollywood, where rapid-fire changes in film technology demanded a steady supply of new products and the ingenuity of those products in turn afforded producers and directors greater creative possibilities. Factor managed to keep pace with major innovations in film stock, lighting, special effects, and overall aesthetic, all of which required new makeup formulations and new methods of application. As the telescopic power of the camera increased, so did the sophistication of his formulas.

He devised the first made-for-film sweat, tears, and blood, and invented a pie topping that was cheaper than dairy cream and stuck to the face longer. He created makeup for painting teeth white and gums pink, makeup that was waterproof, and makeup that could be airbrushed onto body parts (originally used to assist the casting of white actors in non-white roles, but released to the public during World War II when women were encouraged to replace their nylons with leg makeup). Given early lipsticks’ tendency to seep into the corners of the mouth, Factor drew “rosebud” lips, a style of application that accentuates the two upper points and leaves the outer corners bare. When he mastered a formula for lipstick with more staying power, he elongated the shape to create “cupid’s bow” lips, made famous by Clara Bow, and created Joan Crawford’s distinctive look after the invention of lip liner, which made it possible for women to draw their lips in whatever shape they pleased. In the late 1920s, film sets switched from carbon arc lights to incandescents, which were more diffuse and less bright. The hazy quality of this light lent itself to a more ethereal aesthetic; ever responsive, Factor dyed his clients blonde, invented lip gloss, and sprinkled gold dust in Marlene Dietrich’s coif.

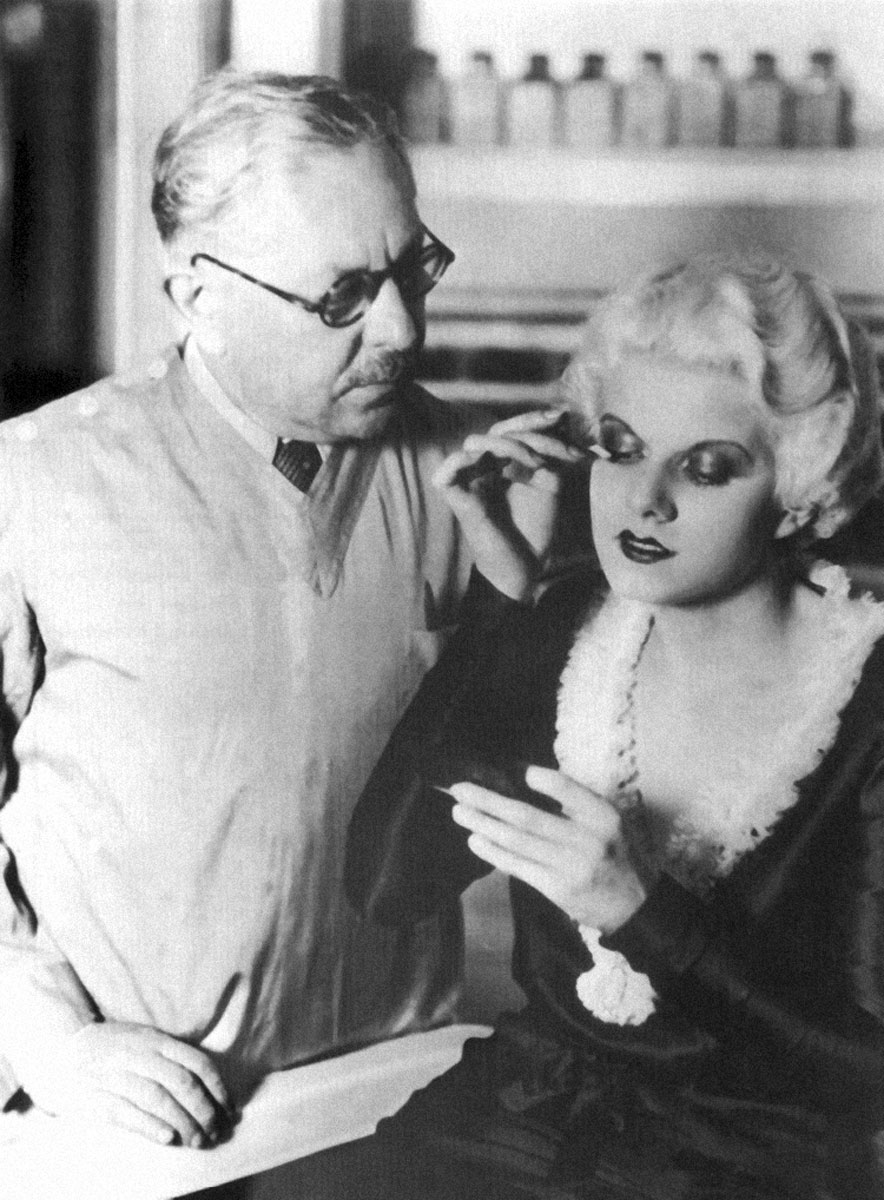

Many of Factor’s most ingenious solutions were custom-designed for specific actors. When Rudolph Valentino complained that he was always cast as a gangster or a villain, Factor developed a special shade of greasepaint that lightened his skin and launched his career as a heartthrob. Colleen Moore’s eyes were different colors, a problem solved with an extreme haircut. Moore’s severe bangs not only drew attention away from her eyes, but became emblematic of the 1920s flapper. Factor was retained on set to keep Douglas Fairbanks’s cheeks smooth as a baby’s, shaving and reapplying the actor’s makeup as often as four times a day. For Phyllis Haver’s career transition from comedy to drama, Factor made her dramatic fake eyelashes; when Gloria Swanson undertook a similar transition, Factor redid her eye makeup with darker colors and gave her a sleek, rather than curly, hairstyle. In the late 1920s, producers began working with panchromatic film stock, which improved the fidelity of colors on the lighter end of the spectrum and launched the mania for blonde actresses. Factor did his part by concocting a new hair dye for Jean Harlow’s performance in a film titled Gallagher. The color was so striking that the studio publicists campaigned to re-title the film, and Platinum Blonde—the color and the movie—made Harlow a star.

For problems that could be solved with wigs rather than haircuts, Factor devised a rental system that made high-quality, realistic hairpieces affordable to producers. Indeed, Factor’s hairpieces, painstakingly crafted using human hair, were far preferable to those used on early film sets: wigs made of mattress stuffing, and stubble made of tobacco flakes. It was said that Factor was such a hair connoisseur that he could identify hair that had never been dyed or artificially curled by smell alone. Insisting that his wigs be made only of such “virgin” hair, he sourced most of his supply abroad and paid a premium for silky red or white hair. Through his salon’s back door, Factor discreetly fitted stars—among them Fred Astaire, George Burns, John Wayne, James Stewart, and Frank Sinatra—for toupees, and invented a scalp prosthetic so that actors could play a bald-headed man in one scene and display a full head of hair in the next. Factor’s studio also designed and fitted underwear for chimpanzee actors in the popular Tarzan films—the Production Code demanded that the apes’ genitalia be camouflaged—and at the peak of its fame, in 1938, it crafted 903 elaborate white wigs for Marie Antoinette (directed by W. S. Van Dyke).

Though Factor’s innovations may at first glance seem minor, they were amplified a million times over by the new visibility of screen stars. Actresses were the beauty mavens of the early twentieth century, and their looks were carefully studied. Audiences noted a red nail, an ultra-thin eyebrow, a smudge of gray eye shadow, and returned home to mimic the look. The imitative jump from film to audience was reinforced by clever marketing: matinee screenings included on-stage demonstrations of hair and makeup techniques, and cosmetic counters displayed movie stills side-by-side with how-to instructions. Mannequins were made up like actresses and one Los Angeles drugstore, The Owl, featured an actual stage where movie stars made guest appearances. Film had such an influence on style that it is not hyperbole to claim, as do several historians, that the appearance of American women in the 1930s can be almost entirely attributed to Greta Garbo.

Mainstream audiences, however, lived off camera, where they were occasionally chastised for donning lipstick or powder, and some were even fired for wearing the stuff at work. Makeup carried the lingering taint of prostitution through the 1920s, to the degree that a police officer might demand a woman go wash her face. Cosmetics were better tolerated when they were inconspicuous—women’s magazines and media pundits alike begged women to apply their makeup with a subtle hand, and to please, please, not put it on in public. Natural-looking makeup was the gateway to social acceptability, the compromise position between women who were inexorably drawn to the possibility of dramatically altering their appearance and men who bemoaned the loss of “sweet, clean” kisses.[1] Curiously, cinema was pushing in exactly the same direction. In 1918, an actress would cake her face with greasepaint and lift the angle of her nose with silk thread, but by 1935, such obvious artifice was unthinkable. As the magnifying powers of the camera increased and Technicolor film made its debut, the standard for screen makeup became invisibility. The zenith of Factor’s career was his invention of a product that simultaneously met the market demand for an innocuous, subtle makeup and the film industry’s need for a substance that beautified while looking convincingly natural.

Factor had worked assiduously during the transition from orthochromatic to panchromatic film, racing to patent a makeup line uniquely suited to the new stock. His efforts won him an award from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 1928, but the formula had to be entirely scrapped for Technicolor.[2] Experiments in Technicolor film had been going on for some time, but studios only reluctantly embraced the technology. Shooting in Technicolor was more expensive, the camera more cumbersome, and the process entailed hiring a specialized crew, including a meddling and powerful color consultant, Natalie Kalmus, whose position was the result of her divorce settlement with her husband Herbert, Technicolor’s co-inventor. Neither were audiences clamoring for more color films. Technicolor seemed a novelty and audiences sometimes complained that it hurt their eyes.

By the mid-1930s, producers and directors began to feel more confidence in Technicolor, but actors still resisted. Bette Davis, Joan Crawford, Greta Garbo, Norma Shearer, and others all refused to appear in color, rightly convinced that their makeup wasn’t an adequate buffer against the aggressive candor of Technicolor film. Factor faced a formidable challenge. He needed a substance that was matte instead of glossy; stable even on the sweatiest face; perfectly matched in color to real skin, which encompasses a spectrum far more complex than Factor’s usual palette of yellow, pink, and white; and finally, with a viscosity that blended with skin rather than masked it, and thus became invisible to the camera. Factor’s impossible task was to make skin more perfect—more even in color and texture than it naturally is—but to do so through imperceptible means.

In fact, aristocratic aesthetes of both genders had grappled with the same problem for hundreds of years. The word makeup tends to connote brightly colored lips or eyelids, but skin quality has been the more constant obsession. Before the eradication of smallpox, the disease left faces pitted with scars. Makeup concealed these imperfections and gave the appearance of good health, indicated by a complexion that was neither choleric nor sanguine, but perfectly pale—the familiar “lily white.”[3] The material commonly used for maquillage, as it was called, was white powder—copious amounts of it, either set with cold cream or held in place by a mask of egg white. Until the early 1800s, ceruse—made of finely ground lead—was the powder of choice. The best was imported from Venice, where sheets of lead were boiled in vinegar, buried in horse manure, and then ground into a fine powder. Originally used by courtesans in ancient Greece and Rome, ceruse was first adopted by western European aristocrats following Elizabeth’s coronation in 1559. The toilette of the women in the royal court, and many men as well, included applying ceruse to face, hands, chest, and neck.[4]

The malevolent effects of ceruse had little effect on its popularity. The substance caused eyebrows to fall out and the hairline to recede; teeth rotted even sooner than they otherwise did. Celebrated beauties became noticeably less so as the cosmetic swiftly corroded and thinned their skin. In the 1760s, the death of Lady Coventry was attributed to her use of cosmetics, as was that of the famous actress and courtesan Kitty Fisher. And yet, the fashion persisted. Vanity was the culprit, and though risking death for the sake of powdered skin seems incredible, as photographer and fashion auteur Cecil Beaton once observed, “We all have enough of the peacock in us not to be able to dismiss it entirely.”[5] In the nineteenth century, ceruse was finally replaced by a combination of talc, chalk, starch, and rice powder. These substances were less toxic, but the aesthetic effect was strikingly artificial. Women emerged from enameling studios with faces that were described as “whitewashed” and “masked,” and they left streaks of powder on everything they touched.

Factor’s Pan-Cake Make-Up represented a wild leap forward. Factor’s first formulas for a natural-looking, blendable skin makeup were used on the set of Walter Wanger’s Vogues of 1938. The makeup was another Hollywood success: Factor received congratulatory letters from directors, actresses dropped their resistance to color film, and audiences raved that their favorite stars were more beautiful in Technicolor than in black and white. George Folsey, director of photography at MGM, announced: “With Pan-Cake, make-up ceases to be a problem as far as photography is concerned.”[6]

The tip-off that Factor had something even more valuable on his hands, however, was that rather than leave their makeup at the studio, actresses stole it to use at home. Factor initially resisted marketing Pan-Cake to the general public—he still believed makeup was best confined to the stage and screen. But his sons persisted and actresses begged, and finally, the following year, Factor launched Pan-Cake Make-Up with great fanfare. The product release was announced with a full-color advertising campaign and movie star endorsements, and timed to coincide with the debut of George Marshall’s 1938 film Goldwyn Follies, the most lavish Technicolor production to date and the first to contain a screen credit for Factor’s makeup. Pan-Cake Make-Up was not the company’s first foray into the general market, but it was by far the most successful, inspiring more than sixty imitations and trumping the profits of all other Factor products combined. Other pioneers of the cosmetics industry—Helena Rubinstein, Elizabeth Arden, Charles Revson—immediately launched their own versions. Factor’s original product, a solid cake of makeup to be applied with a damp sponge, quickly led to the development of what has since been termed “foundation,” a viscous skin-colored substance that now exists in a bewildering range of options. Foundation can be liquid, solid, or something in between called “powder finish”; sheer, velvet, or reflective; applied with sponge, fingers, or aerosol spray; imbued with pigment spheres, microdiffusion systems, and cellular respiration boosters. Such products might be sold at a breathtaking markup over cost, but they will assuredly not depilate the eyebrows.

It was a startling success for a product so nondescript. Bland in color and subtle in effect, foundation is the most prosaic part of a made-up face, and the most prosaic part of making up. There is no glamour or allure in a bottle of beige liquid. And yet, if the product itself is unassuming, the name Pan-Cake Make-Up signaled otherwise. Powder had been variously termed “enamel” or “maquillage,” while “paint” was used with the implication that makeup was immoral. “Cosmetic” was traditionally reserved for face creams and lotions, but was increasingly adopted in the early twentieth century to make face paint seem more socially acceptable. Guided by his sons’ advice, Factor rejected all of these options and instead chose make-up—a word that, like costume or prop, squarely belonged to theater and film. If not with its formula, with its name Pan-Cake Make-Up frankly declared its artifice, and in doing so, evoked the prescient words of Charles Baudelaire, written some seventy years earlier: “Maquillage has no need to hide itself or shrink from being suspected; on the contrary, let it display itself, at least if it does so with frankness and honesty.”[7] With its playful ring, Pan-Cake Make-Up offered a bit of make-believe to everyday life. Indeed, the product signaled that the distinction between real life and the silver screen—between dressing up for the camera and simply dressing up—was swiftly eroding.

Just months after the success of Pan-Cake Make-Up, there followed a turn of events that bizarrely echoed Factor’s lifework. While traveling on business in the summer of 1938, he received a demand for $200 in exchange for his life. Local authorities chose to handle the incident by entrapping the extortionist with a Max Factor doppelganger. A suitable look-alike was found and costumed, but the extortionist never arrived to collect the cash. Although it ended up being a nonevent, the fiasco caused Factor such debilitating emotional strain that he died a few weeks later, at the age of sixty-one.

The story invites speculation. Having serviced actors his entire career, perhaps Factor couldn’t bear the reversal of someone playing himself. Or perhaps the incident made real a latent anxiety that his products, no longer exclusive to film sets, invited an unsettling fluidity of identity. As it turned out, it wasn’t until Factor’s death that a full doppelganger emerged: after his father passed away, Factor’s son Frank changed his name to Max and assumed control of the company. And then he got to work formulating Munchkin makeup for Victor Fleming’s 1939 Wizard of Oz.

See press about “Making Up Hollywood” on Boing Boing, The Verge, and RAGEMAG.

Additional Sources

Maggie Angeloglou, A History of Make-Up (London: Macmillan Company, 1970).

M. S. Balsam and Edward Sagarin, eds., Cosmetics, Science and Technology, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (New York: Wiley-Interscience, 1972).

Fred E. Basten, Max Factor’s Hollywood: Glamour, Movies, Make-Up (Santa Monica, CA: General Publishing Group, 1995).

David Bordwell, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985).

Helena Chalmers, The Art of Make-Up, for the Stage, the Screen, and Social Use (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1925).

Madge Garland, The Changing Face of Beauty: Four Thousand Years of Beautiful Women (New York: M. Barrows, 1957).

Fenja Gunn, The Artificial Face: A History of Cosmetics (New York: Hippocrene Books, 1973).

Serge Strenkovsky, The Art of Make-Up (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1937).

Neville Williams, Powder and Paint: A History of the Englishwoman’s Toilet, Elizabeth I–Elizabeth II (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1957).

- Cited in Kathy Peiss, Hope in a Jar: The Making of America’s Beauty Culture (New York: Metropolitan Books, 1998), pp. 179–180. Complaints about made-up women were widespread, but these specific words were used in a letter, published in the Seattle Union Record on 26 March 1925, by a writer who identified himself as “Sick-O’-Paint Father.” Sick-O’-Paint complains that after kissing his wife he needs to wash his face, and continues: “It takes more stuff to get her ready to go out than it does to cook a five-course dinner.”

- Despite the recognition from the Academy, Factor’s pastel palette did not suit all skin tones. The failure of Lena Horne’s screen test, for instance, was later attributed to unflattering makeup.

- Paleness was so prized by Queen Elizabeth I, for instance, that she drew delicate blue vein lines on her forehead and décolleté, to give the appearance of translucent skin.

- There is one delightful exception to this history of using camouflage to conceal blemishes. A seventeenth-century fad had men and women employing the opposite visual strategy, that is, they covered their imperfections with patches, or mouche. A typical dressing table included a pile of such patches, cut from velvet, leather, or taffeta, colored red or black, and sometimes in the shape of moons and stars. The patches developed a lexicography and aesthetic all their own, particularly in France. For a time, a horse-and-coachman patch was worn on the forehead, and a tree holding two lovebirds on the cheek. A letter from Richard Steele, the founder of Tatler magazine, shows the complexity of the style, and the challenge of maintaining symmetry:

Madam,

Let me beg of you to take off the patches at the lower end of your left cheek and I will allow two more under your left eye, which will contribute more to the symmetry of your face; except you would please to remove the ten black atoms on your Ladyship’s chin, and wear one large patch instead of them. If so, you may properly enough retain the three patches above mentioned.

I am etc.

- Cecil Beaton, Glass of Fashion (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1954), p. 17. Creams and lotions for the face used ingredients that were equally bizarre, and toxic. Homemade concoctions for clearing or lightening the skin incorporated variously the blood of a nine-day-old “Fat Puppidog”; ass’s milk; horseradish; warm urine from a young boy; olive, whale, and bear oil; beeswax; and dozens of other substances. The chief ingredient of Saliman’s Water, a popular commercial product of the eighteenth century, was liquid mercury. Its application, needless to say, corroded the skin and rotted the teeth. Many African-American women were victims of toxic skin lighteners, including St. Louis housewife Mary C., first admitted to a hospital in 1877 when both of her arms were paralyzed. Only shortly before her death did she confess to religiously using Laird’s Bloom of Youth, a lead-based lotion that promised to make her black skin white.

- Fred E. Basten, Max Factor: The Man Who Changed the Faces of the World (New York: Arcade Publishing, 2008), p. 120.

- Charles Baudelaire, “In Praise of Cosmetics,” in The Painter of Modern Life and Other Essays (London: Phaidon, 1964), p. 34.

Sasha Archibald is a writer and curator based in Los Angeles.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.