Mass Effect

In the shadow of Giant Rock

Sasha Archibald

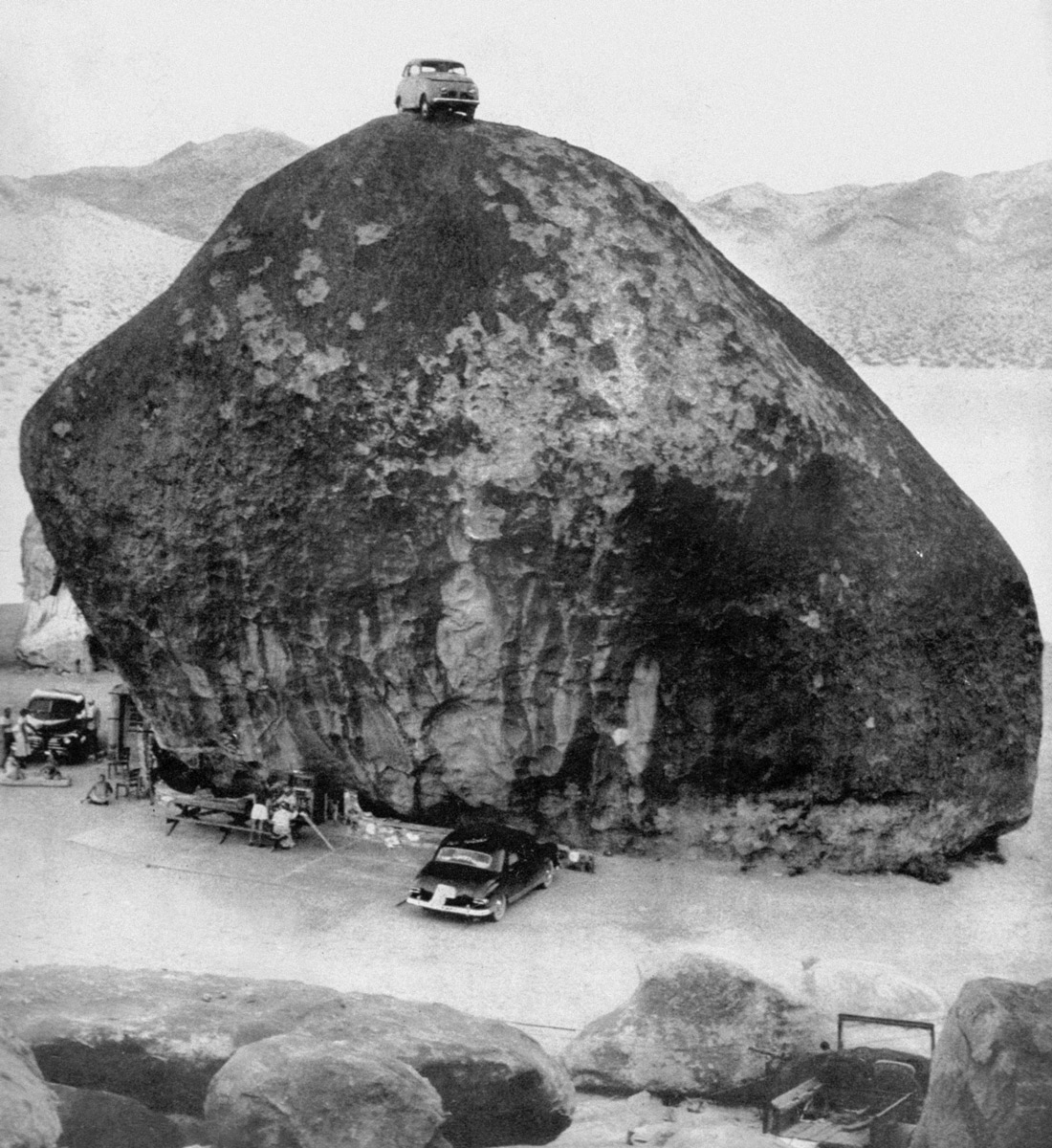

Two hours east of Los Angeles, three hours west of Las Vegas, and many miles from the nearest traffic light or roadside diner lies a single boulder in the Mojave Desert claimed to be the largest rock in the world—at least until 2000, when a large chunk broke off, neatly and without provocation. Now split in two, it is still called Giant Rock. Graffiti blackens the lower surface and ATVs roar nearby. There is an occasional tourist.

For two eccentric Californians, Frank Critzer and George Van Tassel, the immense girth of Giant Rock was not simple geological happenstance but a sign portending mystical significance. In the hands of these two men, Giant Rock became the locus of a strange episode in the twentieth-century history of the American West. Like all Western heroes, Critzer and Van Tassel felt themselves poised between worlds, and at the threshold of civilization. Both felt vitalized and validated by the rock, and both saw it as a natural hub, laboring for decades to make it a gathering place. Absolutely inert and yet fecund, Giant Rock was less a rock than a destiny.

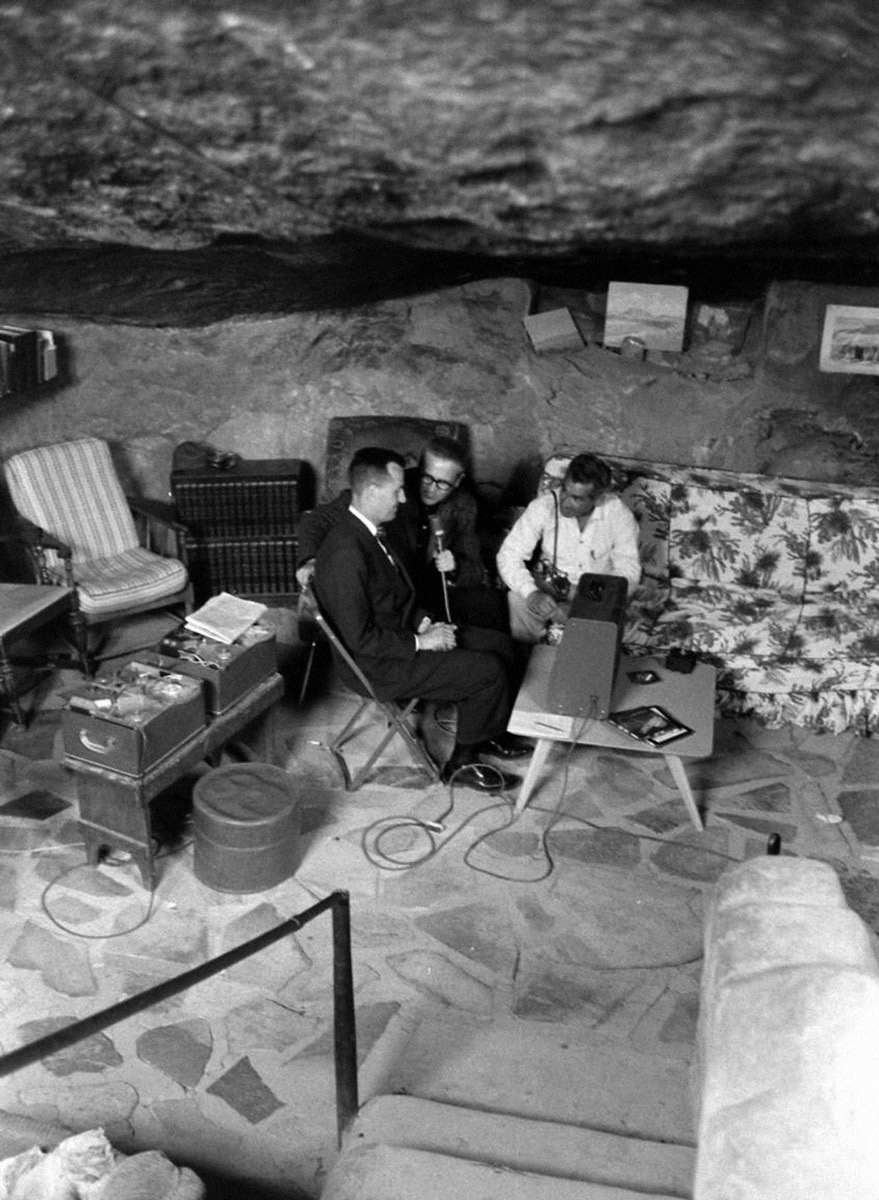

There is little trace of this history at the rock itself, except for a dusty slab of concrete. The concrete conceals a cavern, built by Critzer as a home, and later used by Van Tassel for telecommunication sessions with aliens. No one knows how Critzer stumbled on Giant Rock in the 1930s, or why he decided to move there, but he was obviously clever and resourceful. Critzer saw that the rock’s immense shadow offered succor from the heat and, following the lead of desert tortoises that dig holes in the sand in which to cool themselves, he used dynamite to blast out an abode beneath its north face. Engineering a rainwater-collection system and a narrow tunnel for ventilation, the home he excavated was never warmer than eighty degrees Fahrenheit and never cooler than fifty-five. Perfectly suited to its site, Critzer’s abode refuted the paradigmatic inhospitality of the desert.

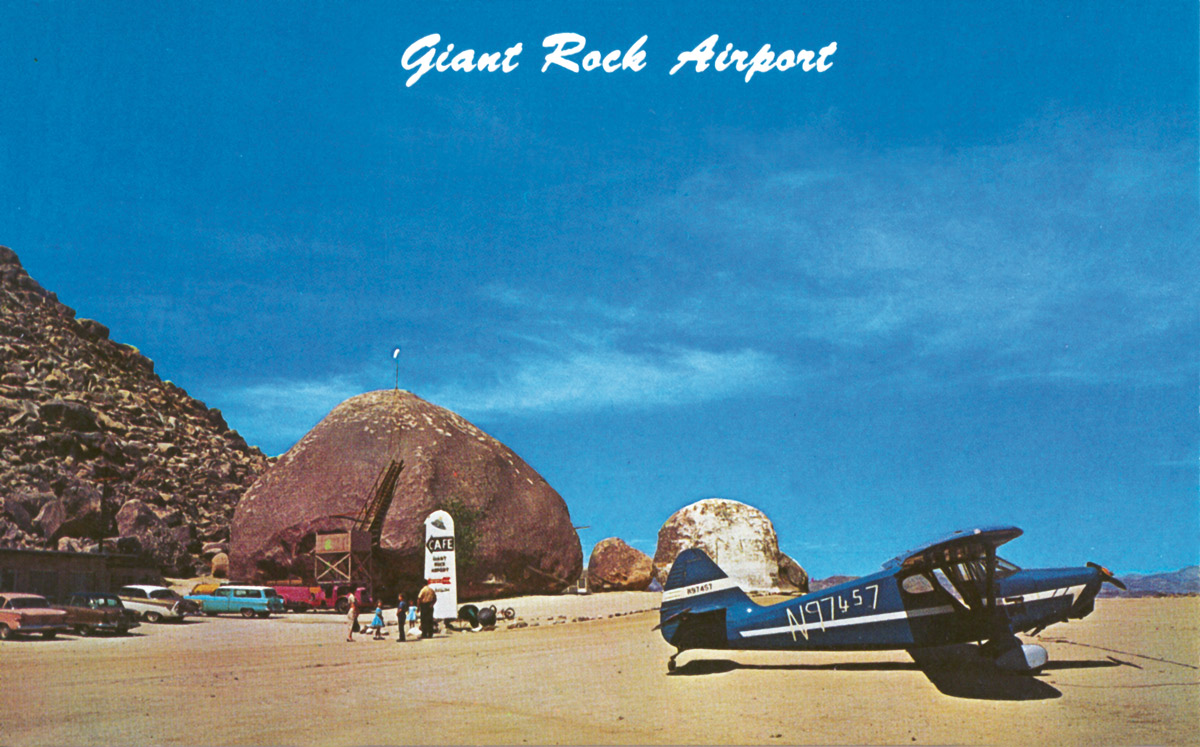

The area surrounding Giant Rock at the time was untrammeled, uninhabited government land, marked on maps as “unsurveyed.”[1] Critzer was a squatter, and his closest neighbor, Charles Reche, a long five miles away.[2] No more than half a dozen men had seen Giant Rock in the last two decades, Reche told Critzer, and Critzer, motivated by entrepreneurial ambition, loneliness, or the pioneer’s sense of duty to domesticate the landscape, took that as a challenge. Giant Rock sits beside an ancient lakebed, flat and firm, which Critzer transformed into an airplane runway, dragging a leveler behind his 1917 automobile. Tacking up a windsock and whitewashing a nearby boulder—Giant Rock is only the largest of many towering rocks in the vicinity—Critzer opened Giant Rock Airport for business. Then he turned to the terrain, using his car to clear thirty-three miles of road that eventually connected Giant Rock to two mines, Reche’s home, and, finally, the nearest paved street. A 1937 article about Critzer in the Los Angeles Times admiringly described these homemade roads as “the straightest desert road that anybody ever saw,” reckoning that Critzer held the world record for one-man road building.[3]

By 1941, Critzer’s Giant Rock Airport averaged a plane a day, flown mainly by amateur pilots who also kept Critzer supplied with food and company. As legend goes, his visitors ate German pancakes at his kitchen table, their legs propped up on spare boxes of dynamite. Critzer hoped to spur investment in the area, and fantasized about opening a winter resort. His plans came to naught. On 25 July 1942, during a police visit gone awry, Critzer’s stash of dynamite exploded and he was killed. His exit from Giant Rock is as shrouded in mystery as his entrance; according to various accounts, the three officers were inquiring about missing dynamite, or gasoline theft, or the antennae Critzer used to attract a radio signal. Some speculated that the combination of a German name and isolated airfield during World War II justified a visit. Perhaps the explosion was an accident, or perhaps it happened exactly as the officers claimed, with Critzer shrieking, “You’re not taking me out of here alive! I’m going, but another way, and you’re going with me!” before he blew himself up.[4]

One man was particularly intrigued by these events, and made his way out to Giant Rock from Los Angeles as soon as he could.[5] Thirty-two-year-old George Van Tassel noted that when he arrived, Critzer’s cavern was stripped of belongings and the car gone. The only trace of Giant Rock’s tenant was a bit of blood splattered on the walls of his cave. The United States still had several laws in place that rewarded intrepid settlers with free land, such that Critzer’s industriousness at Giant Rock almost certainly would have guaranteed him legal ownership. At his death, however, the land reverted back to the government’s newly created Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Van Tassel was not deterred, and began brewing a plan to relocate. Five years later, in 1947, he managed to lease the property from the BLM and left Los Angeles for good, bringing along his wife, Eva, and their three young daughters.

There is little record of Van Tassel’s life other than his own words. He dropped out of high school in Ohio and emigrated to southern California, joining the World War II-era aeronautics industry at a time of unparalleled growth and expansion. Though he later glorified his career, describing himself as a flight test engineer, test pilot, or even personal pilot to Howard Hughes, he told the 1940 census-takers he was a tradesman, a tool and die maker. At the time, he was working for the Douglas Aircraft Company in Santa Monica and living in a modest home with his wife and children, as well as his mother-in-law and his wife’s three younger siblings. He moved from Douglas to Hughes Aircraft, and then to Lockheed, leaving the factories for good in 1947, a year of massive layoffs as aeronautics production recalibrated to peacetime. The vacancy of Giant Rock must have presented itself as a golden opportunity.

Relieved of his nine-to-five job and invigorated by the desert environs, Van Tassel began a flurry of activity—writing, meditating, publishing, and building. He founded a religious non-profit, the Ministry of Universal Wisdom, and an associated college, and began mass mailing its official organ, the Proceedings of the College of Universal Wisdom. In a few short years, Van Tassel emerged as a central figure in atomic-era ufology. His first book, I Rode a Flying Saucer (1952), was a diary of alien messages “radioned” by otherworldly intelligences to Van Tassel’s telepathic mind; shortly after, he met aliens in the flesh, whom he described as “white people with a good healthy tan,” all measuring exactly five feet six inches.[6] The leader, Solganda, spoke excellent English “equivalent to [actor] Ronald Colman,” and through thought transference conveyed to Van Tassel directions for building a time machine, the Integratron.[7] The Integratron was to become Van Tassel’s lasting monument.

Like an automatic car wash, the Integratron was an amalgam of architecture and machine. Its purpose was not to transport a fixed body to a different time, as time machines typically do, but to eliminate time’s effect on a body; the machine produced time, rather than suck it away. An architect drafted plans for the building’s distinctive dome-shaped design—two stories high, supported by arched fir beams brought in from Washington state, constructed without any metal, and painted a brilliant white—and Van Tassel broke ground in 1954, on a plot of land three miles south of Giant Rock. Construction proceeded in piecemeal fashion for twenty-four years, up until Van Tassel’s death in 1978. Van Tassel never pronounced his time machine complete, perhaps because he couldn’t achieve the promised effect, or perhaps because funds solicited to complete the Integratron constituted a crucial source of income. It still stands, carefully maintained and fantastically incongruous with the contorted Joshua trees and endless-shades-of-beige shrubbery.

Devotees claim that Van Tassel’s plans for completing the design were stolen, but he may have had no plans. He alternately described the device as very complicated and very simple, and was always inscrutable when pressed about mechanical details. During one television interview, he boasted vaguely that the Integratron was built following the directives of a seventeen-page equation given to him by aliens and tested by specialists in Chicago; elsewhere he said the formula was very simple and made known to him by alien thought transference: f=1/t where (f) is frequency and (t) is time.

In truth, the Integratron was an elaboration of the research of George Lakhovsky, an iconoclastic Russian scientist whose writings circulated among anti-establishment types in southern California. Lakhovsky understood bodies not as factories or battlefields, but as electrical conductors, an analogy that reached back to eighteenth- and nineteenth-century studies in bioelectricity.[8] Individual cells, Lakhovsky argued in his 1925 book, The Secret of Life: Cosmic Rays and Radiations of Living Beings, are designed to receive and transmit electric impulses, with each of the microscopic components of a cell analogous to a component in an electrical battery. Electromagnetic energy causes cells to infinitesimally move back and forth, and the rate of these movements directly corresponds to the health of the living creature. When cells do not receive enough, or the wrong sort of, electromagnetic stimulation, their vibrations slow; a man dies when his cells cease to oscillate.

Lakhovsky believed that the rate of cellular oscillation could be increased through the body’s proximity to metal conductors. Donning a metal bracelet or attaching metal plates to the soles of shoes would create an uptick in cellular vibration and thus improve health. (In Lakhovsky’s limited experiments, a young woman suffering excessive flatulence was cured by wearing a heavy metal belt, and a “cancerous” geranium began to thrive when a coiled wire was attached to its stem.)[9] Lakhovsky’s theories in fact culminated in a device designed to cure cancer, the Multiple Wave Oscillator. This machine existed in several iterations but the main components were two large copper coils of wire buzzing with high-frequency voltage. (Later, Lakhovsky came to believe the coils alone were sufficient, and far more convenient.) The patient sat between these coils for healing sessions of varying duration. The copper coils intensified some cosmic rays and filtered out others, creating a restorative electromagnetic charge that was received by the body’s two coil-shaped receptors—the wavy mitochondria inside each cell and the inner cochlea of the ear—and directly conveyed to individual cells.

Van Tassel made a few inspired changes to Lakhovsky’s invention. He increased the size of the coil so that it was as large as the building itself, lining the entire width of the Integratron with thin copper wire that spirals out from the building’s inner core.[10] The building’s current owners, three sisters who use the space for “sound baths”—sonorous performances of tonal reverberations made by sweeping the rims of quartz bowls with rubber mallets—suggest that the healing area of the Integratron is at the center of this copper spiral, within the building’s circular core. Van Tassel had originally planned otherwise; subjects would be transformed, he wrote, as they walked the interior perimeter of the structure, entering one door and exiting another, in a precise 270-degree arc. In any case, whereas Lakhovsky sought to cure cancer by placing his subjects between two spirals, Van Tassel hoped to restore youth by immersing his subject within a spiral. The other difference, of course, is that while Lakhovsky’s device was transportable, Van Tassel’s was not. Had the Integratron worked as promised, it would have been a healing experience bound up in landscape and pilgrimage. Indeed, even today, it is impossible to disentangle the various effects of the copper spirals, the domed sanctuary, and the desert calm.

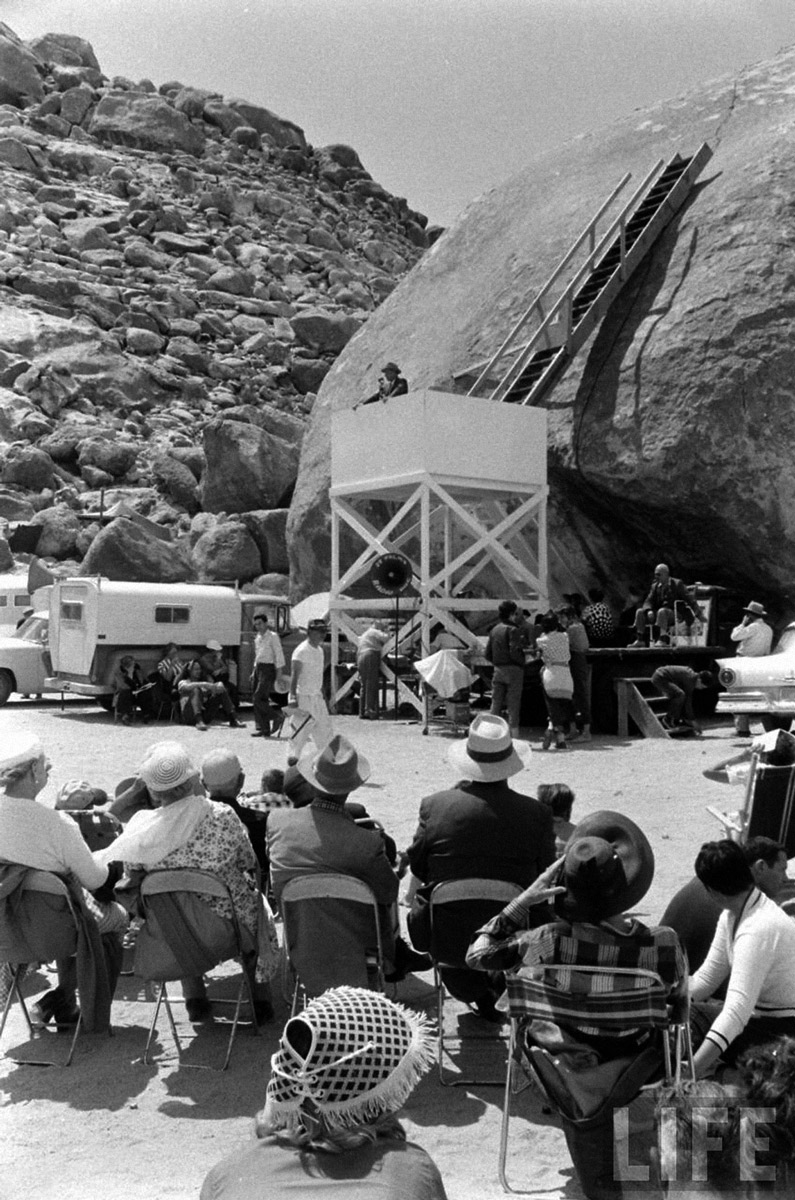

As he was building the Integratron, Van Tassel continued to host an annual UFO convention, an event he first convened in 1953. Critzer’s roads were put to good use as ufologists followed Van Tassel’s hand-drawn map, camping out nearby, exchanging grainy photographs, and beseeching the skies for a mass visitation. There were speeches from a podium almost as tall as Giant Rock and performances by airplane stuntmen; in 1960, Van Tassel went so far as to use the convention to launch his presidential campaign. Attendance was reported at anywhere between three hundred and twelve thousand, depending on the year and source, but it remained a newsworthy event for well over a decade until, in 1970, the Los Angeles Times hinted that Van Tassel might cancel for lack of interest. “People see so many flying saucers, they’re just not a novelty any more,” he lamented.[11]

Van Tassel continued writing, however, eventually publishing four books.[12] His later texts are especially scattered and repetitive, and sometimes degenerate into nonsensical wordplay. Sundry bits of Mesmerism, Mormonism, Scientology, and the writings of Nikola Tesla are patched together with Van Tassel’s tendency to megalomania and enthusiasm for fringe science. He endorses studies proving that a person can tune into the frequency of another by touching a drop of their blood; a head of cabbage mourns the death of another head of cabbage; clothes can be cleaned with sound; breathing patterns will make a man levitate; razors set beneath an inverted pyramid-shape will never dull; and by encircling the city with seven pyramids, Los Angeles could eliminate smog. Sprinkled amid such claims are his biblical interpretations. As a Christian ufologist, Van Tassel understood the Bible as a literal history of interplanetary visitations. Angel, he clarified, is just another word for alien, and the Ark of the Covenant is correctly spelled the Arc of the Covenant.[13]

At dusk at Giant Rock, Van Tassel’s fanaticisms seem benign. To the urban traveler, the desert landscape feels so still and empty that to entertain an improbable something is a sympathetic alternative to accepting an apparent nothing. Van Tassel and Critzer understood the desert void to be a deception; emptiness was only a disguise for an invisible force field, a potent thrum of archaic energy. Van Tassel liked to muse on the fact that his first name, George, contained not one but two combinations of the letters ge, which he understood to be an acronym for Generate Electricity, while Critzer, not to be outdone by his successor, is remembered for boasting that his body was so full of energy he could recharge batteries by sleeping with them under his pillow. In the midst of a blistering nothing, Giant Rock was the totemic conductor of a great something.

- Lynn J. Rogers, “Pioneer Establishes Unique Desert Home,” The Los Angeles Times, 9 May 1937.

- Reche was the owner of an original Mojave homestead dating from the previous century, and also a local hero; he was a former police sheriff permanently injured during the famous 1909 manhunt for Willie Boy, a Chemehuevi Indian who kidnapped a girl to whom he was engaged, killed her father, and escaped to the backcountry. Led by a bloodthirsty posse, the manhunt lasted nearly three weeks and ended in the girl’s murder and Willie Boy’s suicide.

- Lynn J. Rogers, “Pioneer Establishes Unique Desert Home.”

- “Dynamite Suicide Climaxes Desert Search,” The Los Angeles Times, 26 July 1942.

- Van Tassel claimed he knew Critzer from a chance meeting years previous when Critzer had stopped by an auto repair garage in Santa Monica owned by Van Tassel’s uncle. According to Van Tassel’s story, Critzer was down on his luck and needed a car repair; they fixed the car for free, let Critzer crash on the garage floor, and sent him off the next day with $30 and a backseat of groceries. Critzer subsequently mailed Van Tassel a map of his whereabouts and Van Tassel made the first of many visits to Giant Rock. The story may be mostly true, but has some inconsistencies. Van Tassel described the automobile as a 1917 four-cylinder Essex, for instance, a model that didn’t exist, and the gift of $30—$400 in today’s currency—seems an extraordinarily generous amount for a young boy and auto mechanic during the Great Depression.

- “The Extraordinary Equation of George Van Tassel,” television interview by Jack Webster for Webster Reports, aired on KVOS, 18 June 1964. Available at www.youtube.com/watch?v=wZbFsFWk__c.

- “The Extraordinary Equation of George Van Tassel.”

- Van Tassel likely encountered Lakhovsky’s work not through primary texts but through excerpts published by the Borderland Researchers Foundation. The Foundation also published directions for a DIY Multiple Wave Oscillator (MWO), no bigger than a briefcase and under fourteen pounds: “The deluxe MWO diagrammed here can be built by any intelligent 16-year-old with readily available electronic parts for under $35.” The instructions resulted in at least one FDA sting. See Bob Beck, “The Russian Lakhovsky Rejuventation Machine,” Journal of Borderland Research (November 1963), reprinted in Thomas Brown, ed., The Lakhovsky Multiple Wave Oscillator Handbook (Garberville, CA: Borderland Sciences Research Foundation, 1988), p. 1.

- Lakhovsky reported that plants will grow “tumors similar to those of cancer in animals” when they are inoculated with Bacterium tumefaciens. See Lakhovsky, “Curing Cancerous Plants with Ultra Radio Frequencies,” Radio News (February 1925), reprinted in Thomas Brown, ed., The Lakhovsky Multiple Wave Oscillator Handbook, pp. 34–37.

- Aluminum foil was to have lined the interior of the Integratron’s high, rounded ceiling and intensified the electromagnetic rays.

- Charles Hillinger, “Flying Saucer Business Not What It Was,” The Los Angeles Times, 29 March 1970.

- He also claimed to have given exactly 297 lectures and appeared on 409 radio and TV shows, numbers that cannot be substantiated.

- Van Tassel’s interpretation of Genesis is particularly disconcerting: Eve was not a woman but a wild animal, and the original sin to which Christian doctrine refers was bestiality. Through Eve’s debased genetic line descend all the horrors of the modern world: materialism, corruption, nuclear bombs, and even taxes.

Sasha Archibald is a writer and curator in Los Angeles, and a frequent contributor to Cabinet.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.