Artist Project / Cyclura nubila

At Guantánamo, bare life and borders

David Birkin

These people are very gentle and timid; they go naked, as I have said, without arms and without law.

—Christopher Columbus, diary entry of 4 November 1492

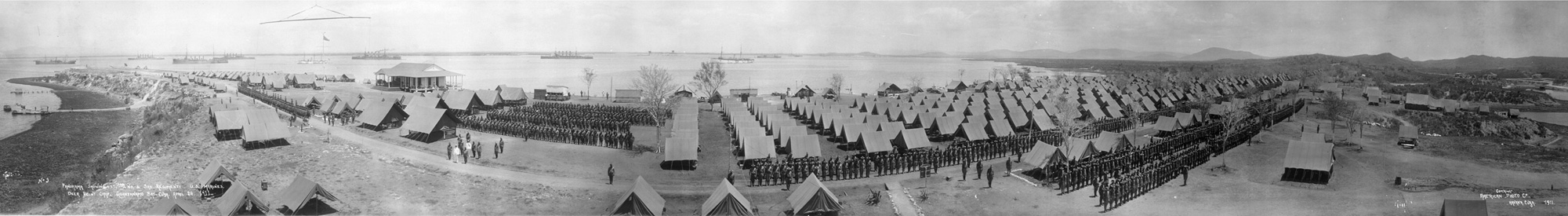

Situated on the southeast coast of Cuba, the natural harbor of Guantánamo has been colonized continuously for over half a millennium. Named by the indigenous Taíno, who inhabited the island before their communities were wiped out by the arrival of Europeans, this “land between rivers” is home to the sole US military base in a communist country, and was, until the recent rapprochement, the site of the only base in a country with which the United States did not maintain diplomatic relations.

President Theodore Roosevelt’s administration began leasing territory around Guantánamo Bay from the nascent Cuban government following Spain’s defeat in the Spanish-American War of 1898. As a condition for the withdrawal of US troops, the 1903 Cuban-American Treaty of Relations asserted the imperial power’s right to buy or lease Cuban lands for its own defense, as well as “to maintain the independence of Cuba, and to protect the people thereof.” Although much of the treaty was abrogated in 1934 as a result of the “Good Neighbor” policy toward Latin America instituted by Theodore’s cousin Franklin D. Roosevelt, Naval Station Guantanamo Bay—or GTMO, in military parlance—is one remnant that remains operational.

Under the terms of the agreement, Washington exercises complete jurisdiction and control over the land, while ultimate sovereignty resides with Havana. Rent for the forty-five-square-mile former coaling station has been fixed at $4,085 per annum since 1938. The lease is perpetual, and can only be terminated by abandonment or by the mutual agreement of both parties. After the revolution of 1953–1959, the new government of Fidel Castro, arguing that the treaty had been imposed under duress and was incompatible with modern international law, stopped cashing the checks. But the United States keeps sending them anyway—an unwanted tenant who knows not to miss a payment.

The Cold War-era “Cactus Curtain,” an eight-mile stretch of heavily fortified prickly pear planted in 1961 near the base to deter Cubans from defecting in the wake of the Bay of Pigs invasion, still makes itself felt from time to time as the island’s giant banana rats scurry across the mines that line the Cuban side.

The name “Guantanamo” entered the public consciousness this century following the attacks of September 11 as a synonym for the Bush administration’s program of rendition and detention. After the invasion of Afghanistan in October 2001, the United States began offering bounties of thousands of dollars a head for the capture of alleged Taliban and al-Qaeda fighters. Flyers promising “wealth and power beyond your dreams” and “enough money to take care of your family, your village, your tribe for the rest of your life” were strewn across Afghan villages “like snowflakes in December in Chicago,” as Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld himself put it. The tactic yielded results, but at the expense of accuracy as hundreds of innocent Afghans and foreign nationals—including Saudis, Yemenis, Pakistanis, and ethnic Uighurs escaping persecution in China—were apprehended by local warlords and turned over to the Americans, with boys as young as twelve and men as old as ninety-three being shipped off to Guantanamo. Once images appeared in the press of prisoners shackled in those now-infamous orange jumpsuits, sensory-deprived and kneeling behind rows of razor wire, it became politically expedient to simply leave them there, as depictions of alleged terrorists in US custody could be used to signal success in the military campaign, while admissions of error would call into question the government’s handling of the war. Thus began a narrative whereby “the worst of the worst” had to be kept off American soil.