The Mansion House Tavern of Crossed Destinies

Reading the tarot deck of Austin Osman Spare

Jonathan Allen

In Raymond Roussel’s proto-surrealist novel Locus Solus (1914), the proprietor of a country estate, Martial Canterel, conducts a tour of his extensive grounds, presenting his guests with a sequence of increasingly eccentric and spectacular inventions. In the book’s penultimate chapter, the group encounters Felicity, a “renowned sibyl” in possession of a deck of luminous musical tarot cards. As Canterel explains, a talented watchmaker had, at Felicity’s request, inserted within the layers of each card a mechanism harnessing a number of insects of exceptional flatness—so-called emeralds—that when sung to by the sibyl emitted tiny haloes of green light and accompanied her with a melody reminiscent of “The Bluebells of Scotland.”

Roussel’s tarot cards are animated, of course, by nothing more than the writer’s prose. As Michel Foucault observes in Death and the Labyrinth—his sole foray into literary criticism—the insects trapped within Felicity’s cards “do not come from a fantastic forest, nor from the hands of a magician; no spell endowed them with malevolent signals.”[1] Rather they are born from within the material processes of the literary imaginary, which, as Roussel reveals in his posthumous exposé How I Wrote Certain of My Books (1935), had required the laborious, almost machine-like linking together of homonyms and near-homophones. Indeed it was the automaton-like character of Roussel’s art that recommended the writer to André Breton, who viewed him, alongside Lautréamont, as “the greatest mesmerizer of modern times.”[2]

A decade before Roussel wrote Locus Solus, an actual tarot deck that incorporated an unprecedented technology and implicit interiority suggestive of Roussel’s emerald-filled cards was being created in London. Its maker—also described by some as a forerunner of surrealism—was the English artist and mystic Austin Osman Spare (1886–1956), and the hand-painted tarot deck he produced around 1906 has only recently emerged from within the archives of London’s Magic Circle Museum, where it had lain for the past seventy years, accessible only to the clandestine organization’s community of theatrical magicians.

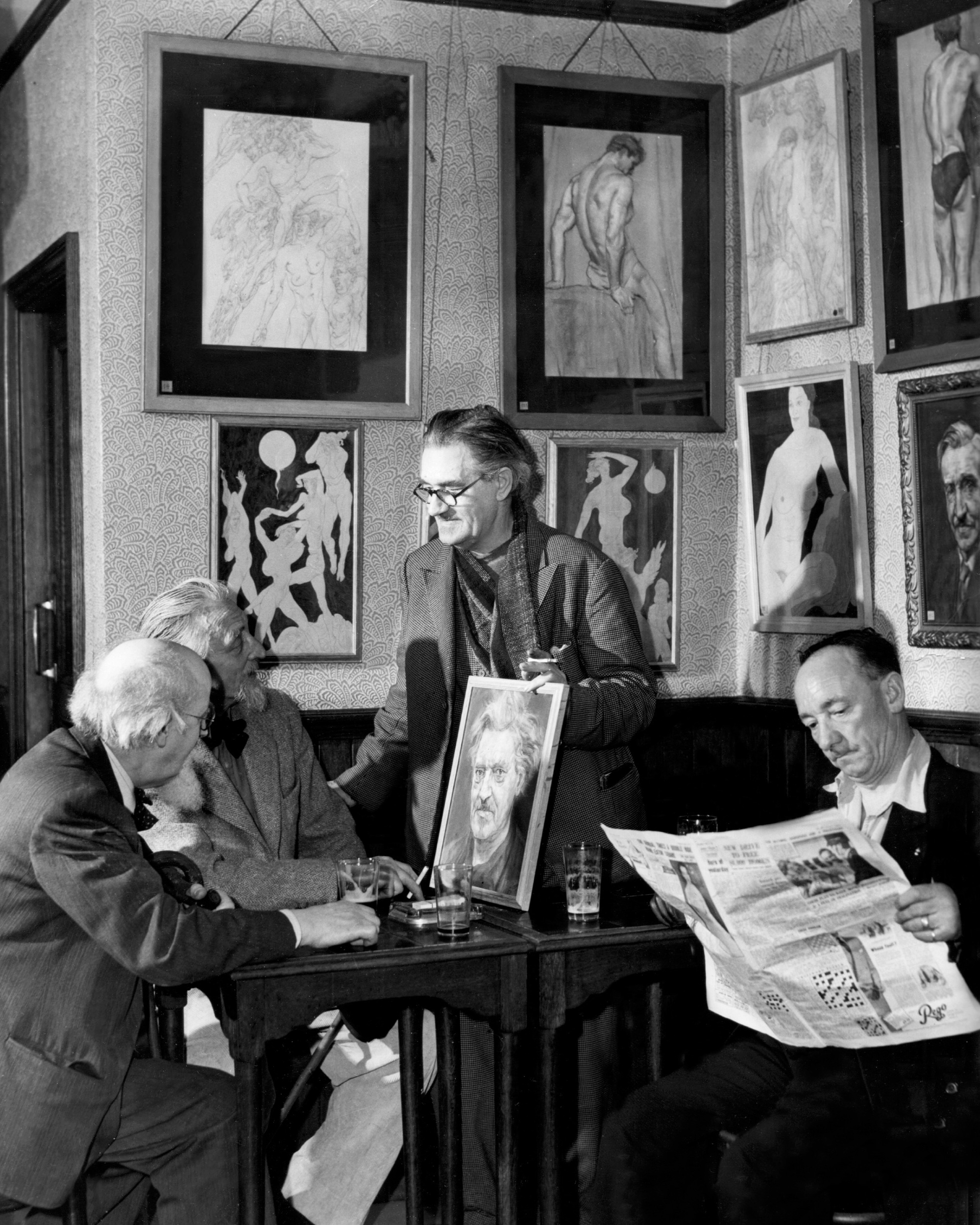

Even in the art world, Austin Spare’s name often passes unrecognized. The son of a policeman, Spare was born in London’s Smithfield neighborhood in 1886. At a young age he was embraced by the art establishment and hailed a “genius” by the popular press due to his remarkable talent for drawing and his precocious inclusion in the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition of 1904. Spare’s biographer Phil Baker observes that, despite his early professional success, the artist “had his career the wrong way round … he began as a controversial West End celebrity and went on to obscurity in a south London basement.” Baker cites the “hidden injuries of class” as a factor in Spare’s troubled professional trajectory but an equally significant factor during his lifetime may have been his claim that mystical practices lay behind the production of his artwork, as well as his association with influential occultists, including the notorious mage Aleister Crowley.[3] In recent years, as cultural historians have acknowledged the important influence of occult histories on the development of twentieth-century modernity, Spare’s work has been read more sympathetically. For a younger generation of artists, he has become something of a folk hero, a tenacious antiestablishment sorcerer whose penchant for mounting exhibitions in the wood-paneled taverns of south London has only added to his dissident appeal. Spare’s work is now in collections around the world, with significant examples in the United Kingdom at the Victoria & Albert Museum, the Imperial War Museum, and the Wellcome Collection.