Electric Caresses

Rilke, Balthus, and Mitsou

Dominic Pettman

In 1920, as Europe reeled from the Great War, as well as from all the questions about human nature and progress it provoked, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke visited a close friend, Elisabeth Klossowska, near Lake Geneva. This woman had a twelve-year-old son, who would grow up to be known simply as Balthus, a painter notorious for his voyeuristic depictions of tender-aged girls, often shown in secret, somber interactions with cats. The critical reflex, when confronted with such imagery, was—and indeed still is—to acknowledge the totemic function of this animal within the frame, which symbolically mirrors the girls themselves (coded as feline, or “kittenish”), while also evoking in plain sight a metaphoric allusion to the taboo part of the subject’s body the painter presumably most desired. But this view changes when we learn about a trauma Balthus suffered a year before Rilke’s visit.

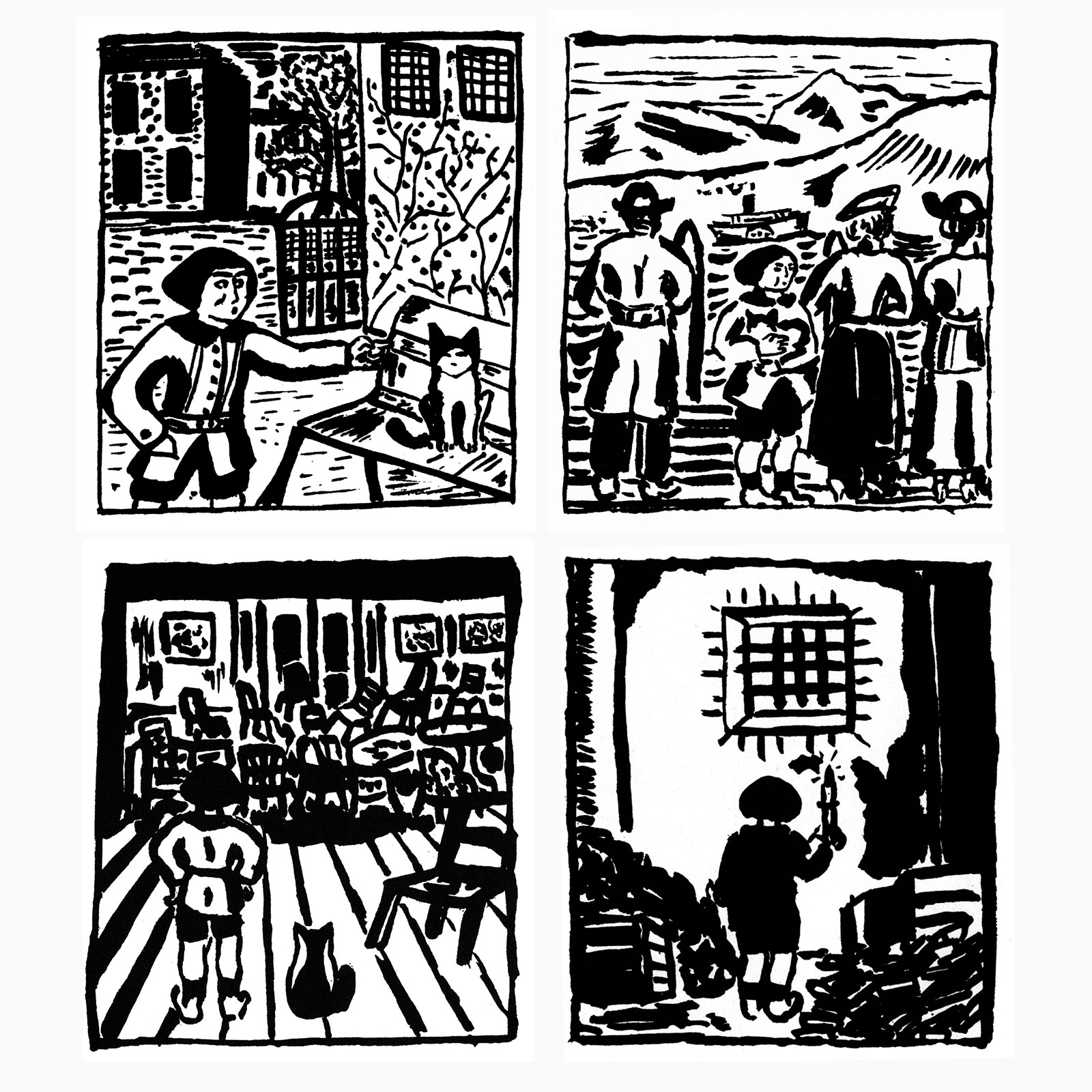

Having taken in a stray cat, the young boy named his new companion Mitsou, and loved his enigmatic adoptee with the unthinking intensity of a sensitive child. But just as quickly as she had come into the boy’s life, the cat disappeared, leaving only a single year of memories. To cope with the devastating pain of abandonment, the precocious Balthus made forty ink drawings of fond moments they had spent together. Mitsou taken to the park. Mitsou keeping the young boy company as he reads a book. Mitsou in Balthus’s arms as the family waits to board a ferry. Mitsou being scolded after the first dress rehearsal for disappearance. And then the last sequence of pictures: the young boy, frantic and disconsolate as he searches for his friend, and finally in tears, distraught as he realizes that Mitsou is gone forever.

When Rilke visited the house, one year after this sad event, he was shown the drawings by the budding artist. The poet was so impressed with the story these told that he arranged for the drawings to be published, even writing a short preface in French for the book. Clearly more than sentimental juvenilia—the celebrated German publisher Kurt Wolff, for instance, called them “astounding and almost frightening”—these pictures shed a different light on Balthus’s later work, which many find uncomfortably pedophilic. (It is no coincidence that one of his paintings, Jeune fille au chat, became a cover image for modern editions of Nabokov’s Lolita.) As one art critic recently noted, “Mitsou almost feels like a lost first love,” an observation that suggests that the cats in his paintings might not simply function as totemic invocations of the young girls.[1]

But why almost? Childhood pets allow an experience of intersubjective intimacy too often cast as merely a passing apprenticeship on the long and winding road to proper, mature, human love; as if the affection one has for a cat, dog, or horse is less meaningful or affectively charged than the feelings one has for a sibling or friend. If we accept that the cats in Balthus’s adult oeuvre represent a real desire directed toward the feline, it becomes clear that his paintings allow, beyond or within the problematic gendered gaze, the refusal to choose between humans or animals when it comes to a privileged object of affection. Or better, they allow us to see a certain continuum between humans and other animals, united in play, in boredom, in domestic daydreams.

Rilke’s preface, however, reminds us not to collapse such a continuum too quickly. He begins by asking: “Does anyone know cats? … I must admit I have always considered that their existence was never anything but shakily hypothetical.” Dogs, in sharp contrast, are much easier to “know,” since they “live at the very limits of their nature, constantly—through the humanness of their gaze, their nostalgic nuzzlings.”[2]

But what attitude do cats adopt? Cats are just that: cats. And their world is utterly, through and through, a cat’s world. You think they look at us? Has anyone ever truly known whether or not they deign to register for one instant on the sunken surface of their retina our trifling forms? As they stare at us they might merely be eliminating us magically from their gaze, eternally replete. True, some of us indulge our susceptibility to their wheedling and electric caresses. But let such persons remember the strange, brusque, and offhand way in which their favorite animal frequently cuts short the effusions they had fondly imagined to be reciprocal. … Has man ever been their coeval? I doubt it. And I can assure you that sometimes, in the twilight, the cat next door pounces across and through my body, either unaware of me or as demonstration to some eerie spectator that I really don’t exist.[3]

In other words, different creatures can inhabit the same objective space (if today’s quantum physicists will allow such a conceit), but not the same phenomenological one. Or to paraphrase Lacan, il n’y a pas de rapport félin. Cat fur may rub along a human leg, but the cat and the human are the loci for two different and unconnected relationships to this instance of physical contact. There is nothing we could describe as a shared experience. (Of course, the same can be said of human lovers.)

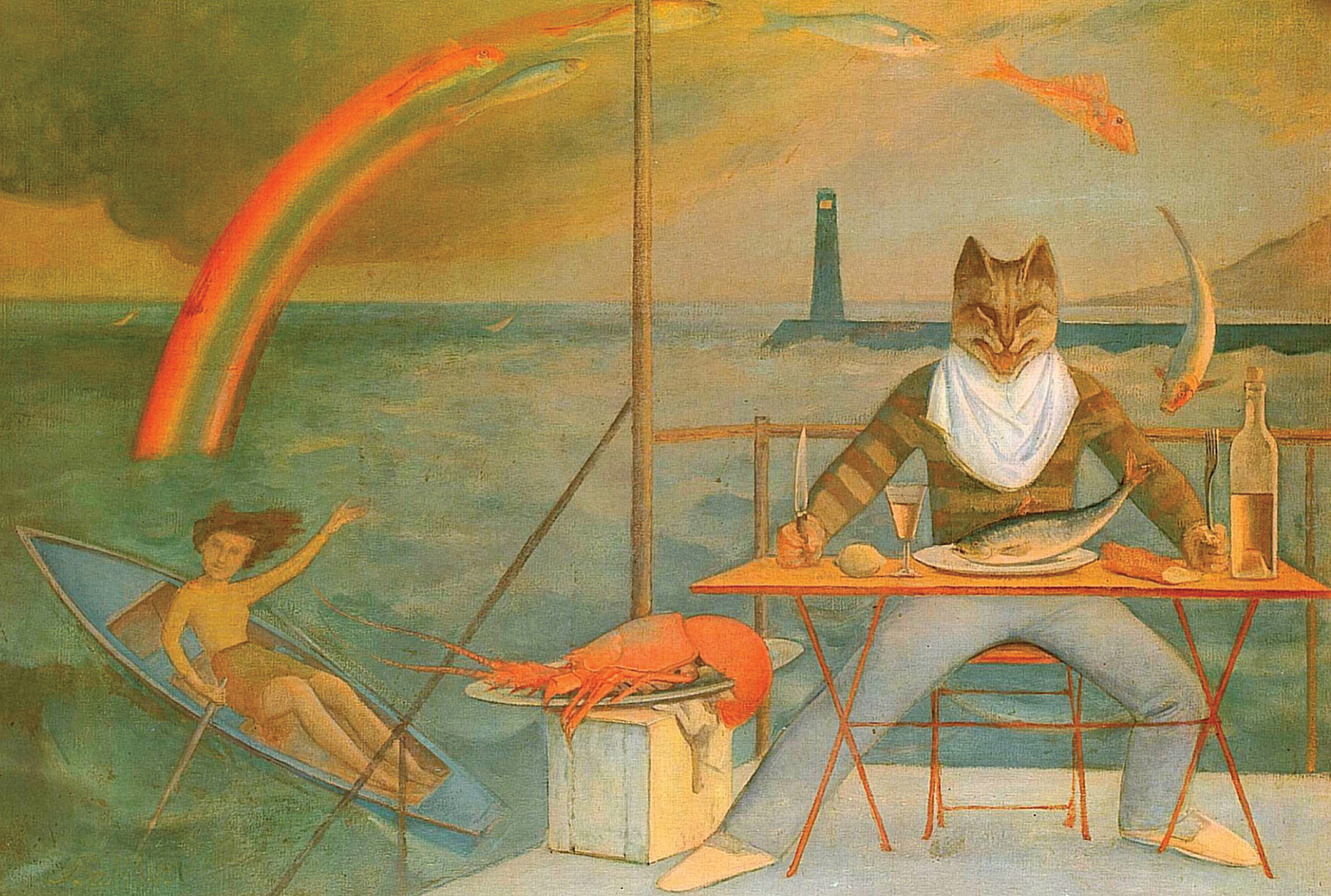

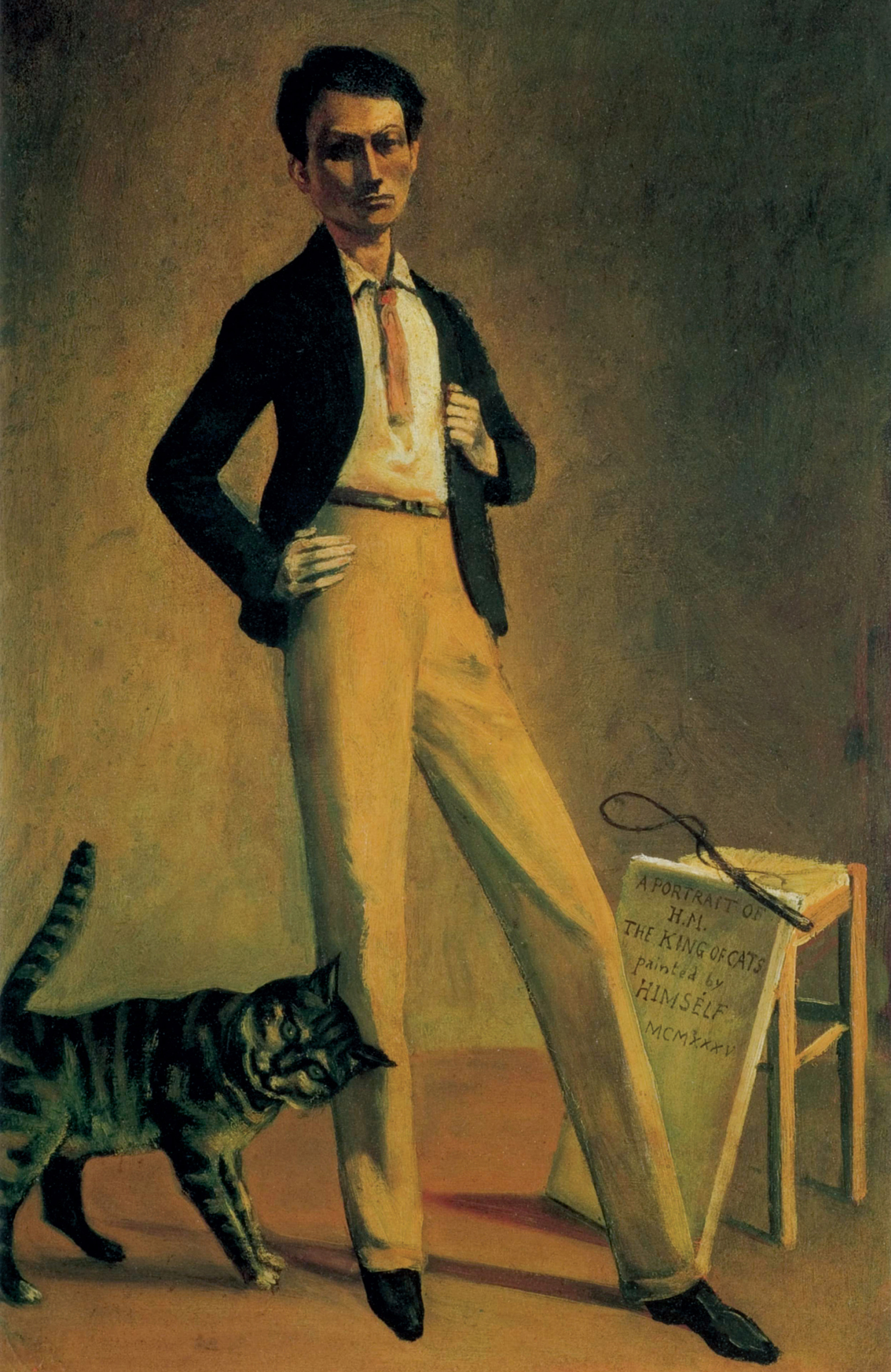

Balthus’s own paintings, however, seem to allow for a space of ontological exchange, or at least a possibility of mutual recognition. In one sense, cats are his subjects, such as the one that stands at his feet in the large self-portrait The King of Cats (1935). In other depictions, the cat has its own sovereign presence and energy, as with The Cat of La Méditerranée (1949), which served as a mural in La Méditerranée, a Parisian restaurant frequented by André Malraux, Albert Camus, and Georges Bataille. Clearly, Mitsou’s soft and elusive fur lived on in many different avatars, produced by the horsetail brushes of her brief “owner.” Art thus fulfills one of its primary functions in fixing, or at least attempting to fix, the evanescent essence of the beloved other; the silhouette of another ensouled body that will soon be, if it is not already, absent.

At the end of his preface, Rilke reflects—in a striking passage so underread that it deserves to be quoted in full—on the melancholic dynamic of unexpected acquisition and loss, bestowing a special role on cats in the ongoing fort/da game that punctuates all of our lives:

It is always diverting to find something: a moment before, and it was not yet there. But to find a cat: that is unheard of! For you must agree with me that a cat does not become an integral part of our lives, not like, for example, some toy might be: even though it belongs to us now, it remains somehow apart, outside, and thus we always have:

life + a cat,

which, I can assure you, adds up to an incalculable sum.

It is sad to lose something. We imagine that it may be suffering, that it may have hurt itself somehow, that it will end up in utter misery. But to lose a cat: no! that is unheard of. No one has ever lost a cat. Can one lose a cat, a living thing, a living being, a life? But losing something living is death!

Very well, it is death.

Finding. Losing. Have you really thought what loss is? It is not simply the negation of that generous moment that had replied to an expectation you yourself had never sensed or suspected. For between that moment and that loss there is always something that we call—the word is clumsy enough, I admit—possession.

Now, loss, cruel as it may be, cannot prevail over possession; it can, if you like, terminate it; it affirms it; in the end it is like a second acquisition, but this time totally interiorized, in another way intense.

Of course, you felt this, Baltusz. No longer able to see Mitsou, you bent your efforts to seeing her even more clearly.

Is she still alive? She lives within you, and her insouciant kitten’s frolics that once diverted you now compel you: you fulfilled your obligation through your painstaking melancholy.

And so, a year later, I discovered you grown taller, consoled.

Nevertheless, for those who will always see you bathed in tears at the end of your book I composed the first—somewhat whimsical—part of this preface. Just to be able to say at the end: “Don’t worry: I am. Baltusz exists. Our world is sound.

There are no cats.”[4]

- Roberta Smith, “Infatuations, Female and Feline,” The New York Times, 26 September 2013.

- Rainer Maria Rilke, introduction to Balthus, Mitsou: Forty Images, trans. Richard Miller (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1984), p. 9.

- Ibid., pp. 9–10.

- Ibid., pp. 12–13.

Dominic Pettman is chair of the Department of Liberal Studies at the New School for Social Research and a professor of culture and media at Eugene Lang College, New York. He has published numerous books, including Human Error: Species-Being and Media Machines (University of Minnesota Press, 2011), Infinite Distraction: Paying Attention to Social Media (Polity, 2015), and Humid, All Too Humid (Punctum Books, 2016). Forthcoming titles include Creaturely Love: How Desire Makes Us More, and Less, than Human (University of Minnesota Press, 2016) and Sonic Intimacies: Voice, Species, Technics (Stanford University Press, 2017).

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.